Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

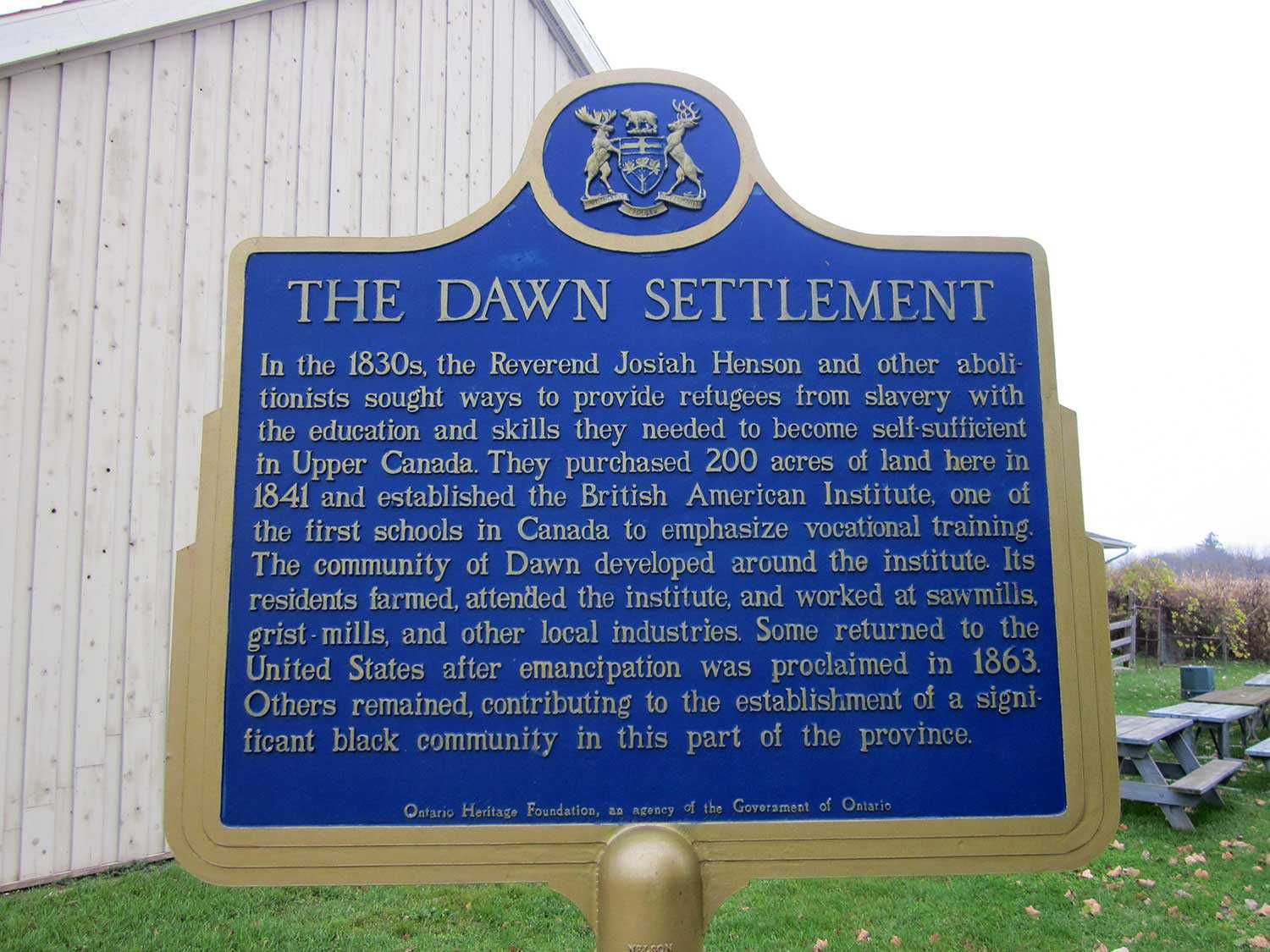

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Heritage conservation districts: The most popular tool in the heritage toolkit?

When the Ontario Heritage Act came into force in 1975, municipalities across the province suddenly had the authority to protect and enhance “groups of properties that collectively give an area special character” by designating these areas as heritage conservation districts – also known as “Part V (section 41) designations” or simply HCDs.

The scope of the act has evolved beyond architectural heritage. The contextual value of a property and the compelling importance of cultural landscapes are now widely recognized. The concept is reflected in legislation and policy documents used to promote good planning practices. The term cultural heritage landscape is defined in the Provincial Policy Statement under the Ontario Planning Act. Heritage conservation districts are cited as an example of cultural landscapes in this definition. In addition, the second edition of the Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada, published in 2010, unequivocally declares that a heritage district is a cultural landscape.

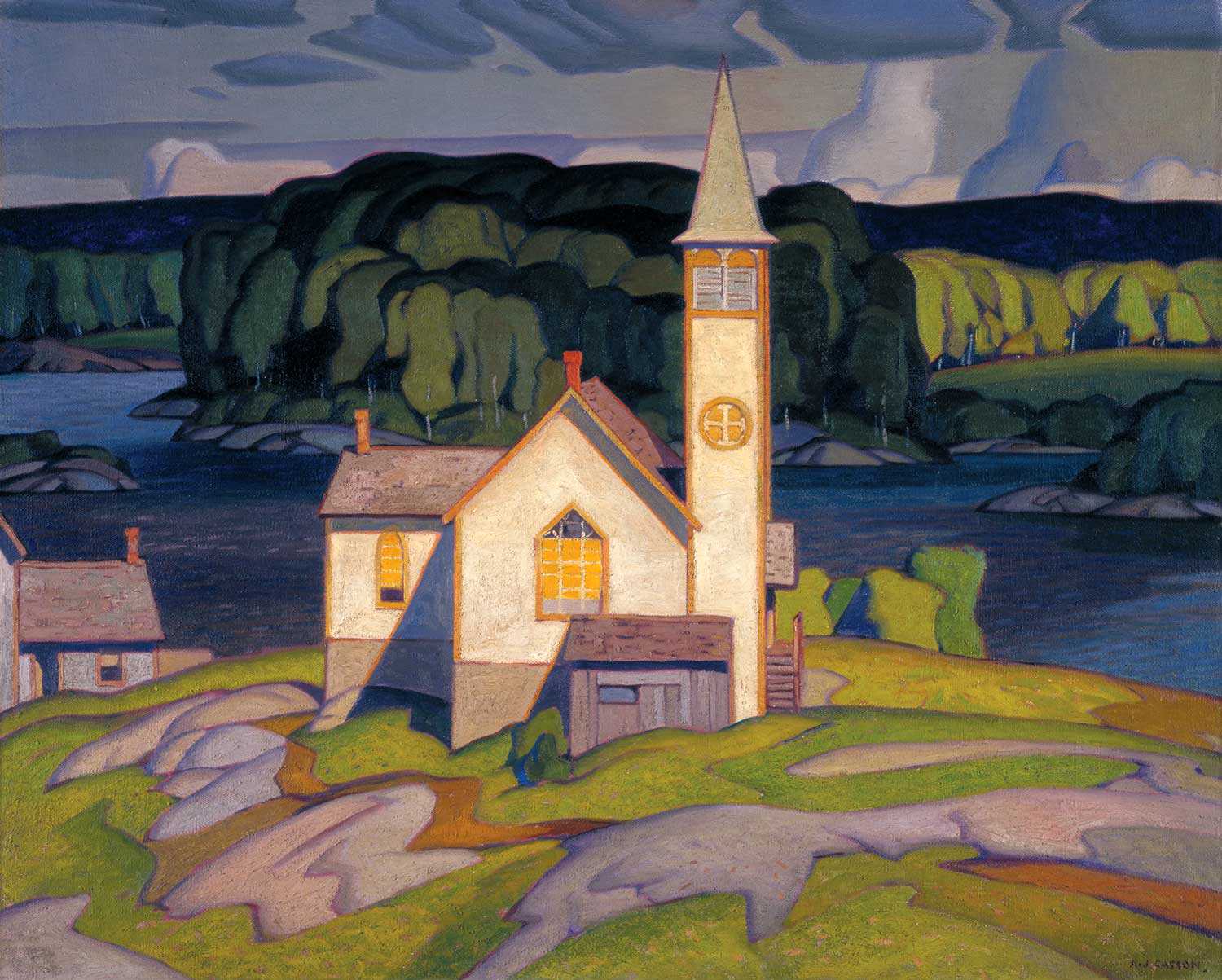

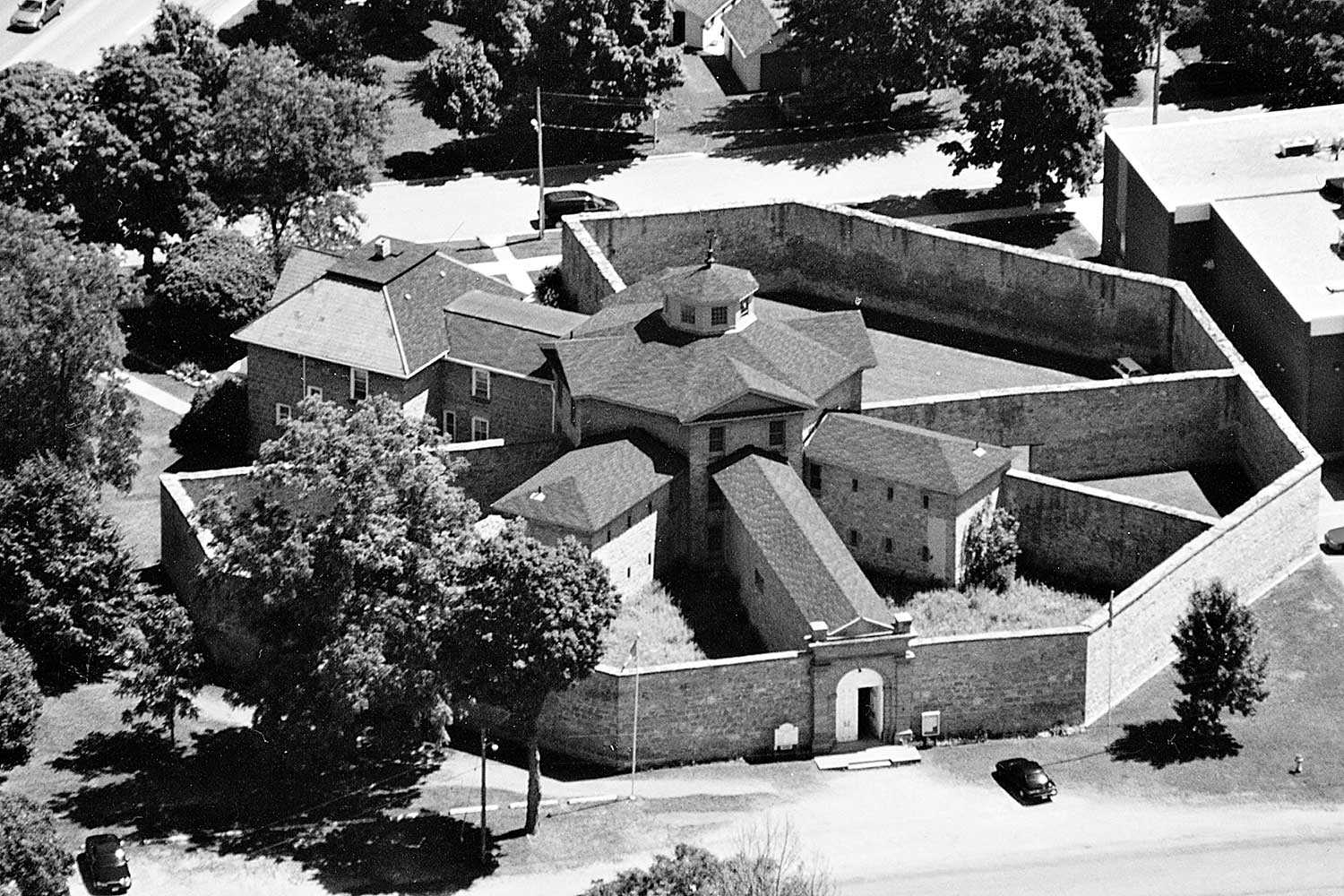

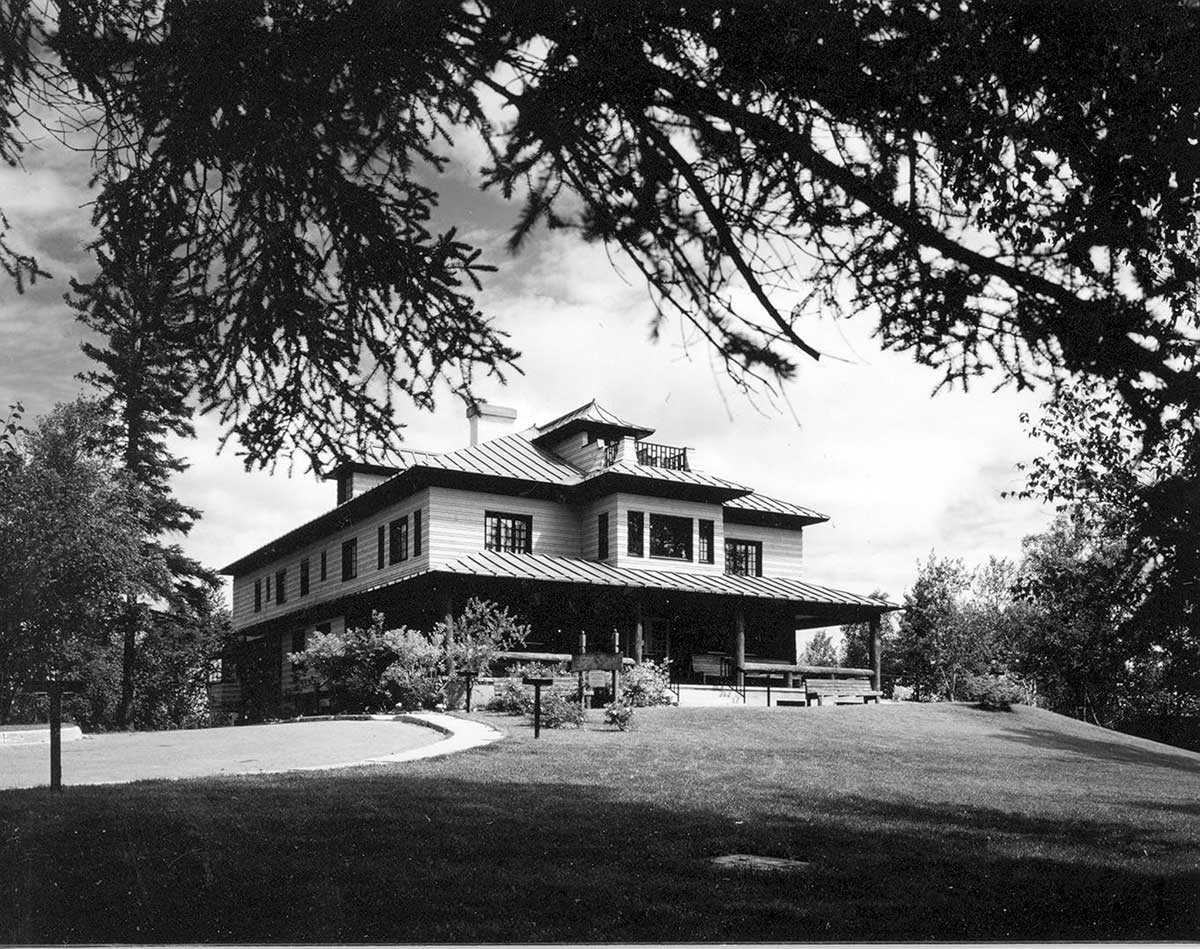

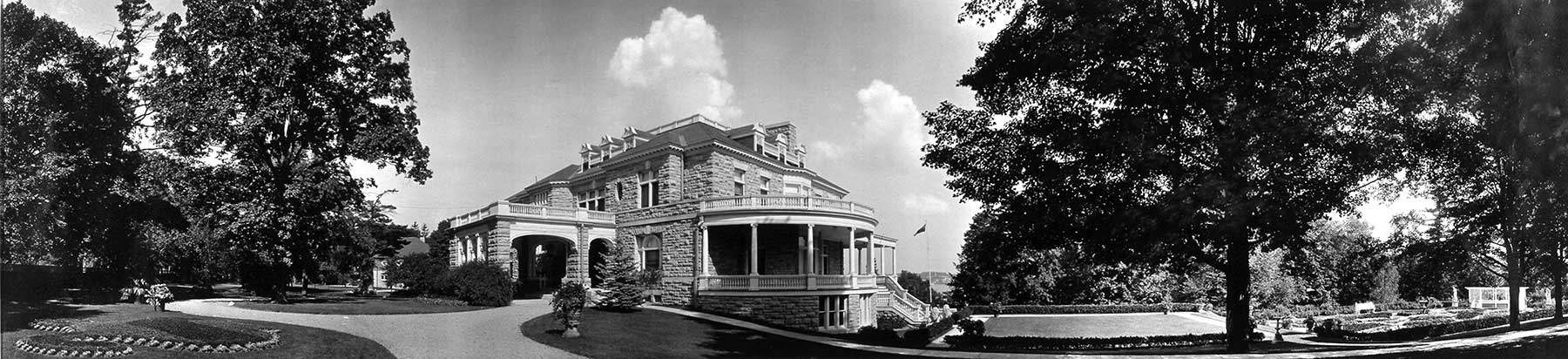

The largest HCD in Ontario is currently South Rosedale in Toronto, comprising over 1,100 residential properties. The smallest district, and Ontario’s only single-property HCD is Fort York National Historic Site (shown here), also in Toronto. Photo courtesy of Doors Open Toronto.

District designation protects these landscapes by first framing a clearly defined geographical area and then describing that area’s dynamic, prevailing character and sense of place. It identifies the interrelated features and attributes that contribute to this character and place, including the built form and surrounding features – such as trees and vegetation, streetscape characteristics, views and vistas, road patterns, landforms and open spaces.

A district designation also establishes an informed heritage planning framework through a district plan to promote conservation and to manage change. Municipalities appear to be relying on this coordinated and holistic approach to heritage conservation more than ever.

Individual property designation is a well established conservation tool. More than 250 municipalities have at least one Part IV (section 29) designation bylaw in place. As effective as this type of designation can be, it can sometimes lead to a conservation patchwork. Isolated landmarks are protected while the surrounding streetscapes or context slowly erodes or disappears. District designation, on the other hand, focuses on distinct areas.

Data from the Ontario Heritage Act (OHA) Register indicates that the rate of individual heritage designations peaked in the 1980s at roughly 230 bylaws per year. Between 2000 and 2009, the average number of new designations dropped to 141 bylaws per year; this trend appears to be continuing.

By contrast, the number of new HCDs has surged in the past decade. Ontario currently has 110 districts in full force. Almost half of these came into being after the year 2000, suggesting that municipalities, property owners and residents are increasingly seeing the merits of this type of protection.

The Trust estimates that, in Ontario, close to 18,000 properties fall within the boundaries of an HCD, compared to no more than 8,000 individual heritage designations. Toronto, Ottawa and Hamilton have the most HCDs with 20, 18 and seven respectively.

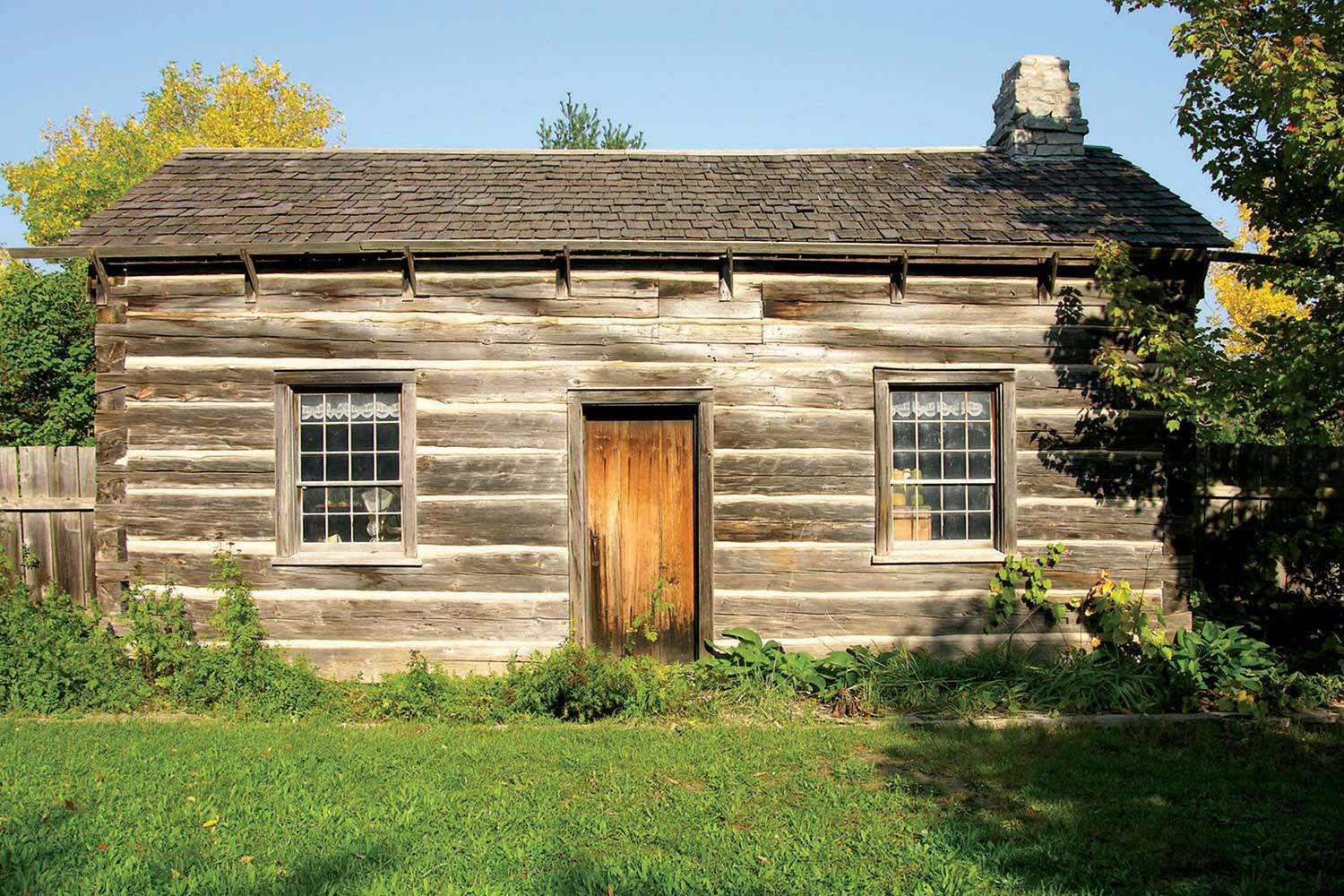

While every district is unique, they can still be grouped and generally categorized. Districts are found in both rural and urban areas. The two most prevalent types of districts are residential neighbourhoods – such as the West Woodfield neighbourhood in London – and downtown commercial areas – such as the downtown cores of Stratford, Cobourg and Cambridge. In fact, 80 per cent of all district types in Ontario are either residential areas or historical downtown cores. Rural settlement areas are another large category and include such districts as Brampton’s Churchville area and Pickering’s Whitevale.

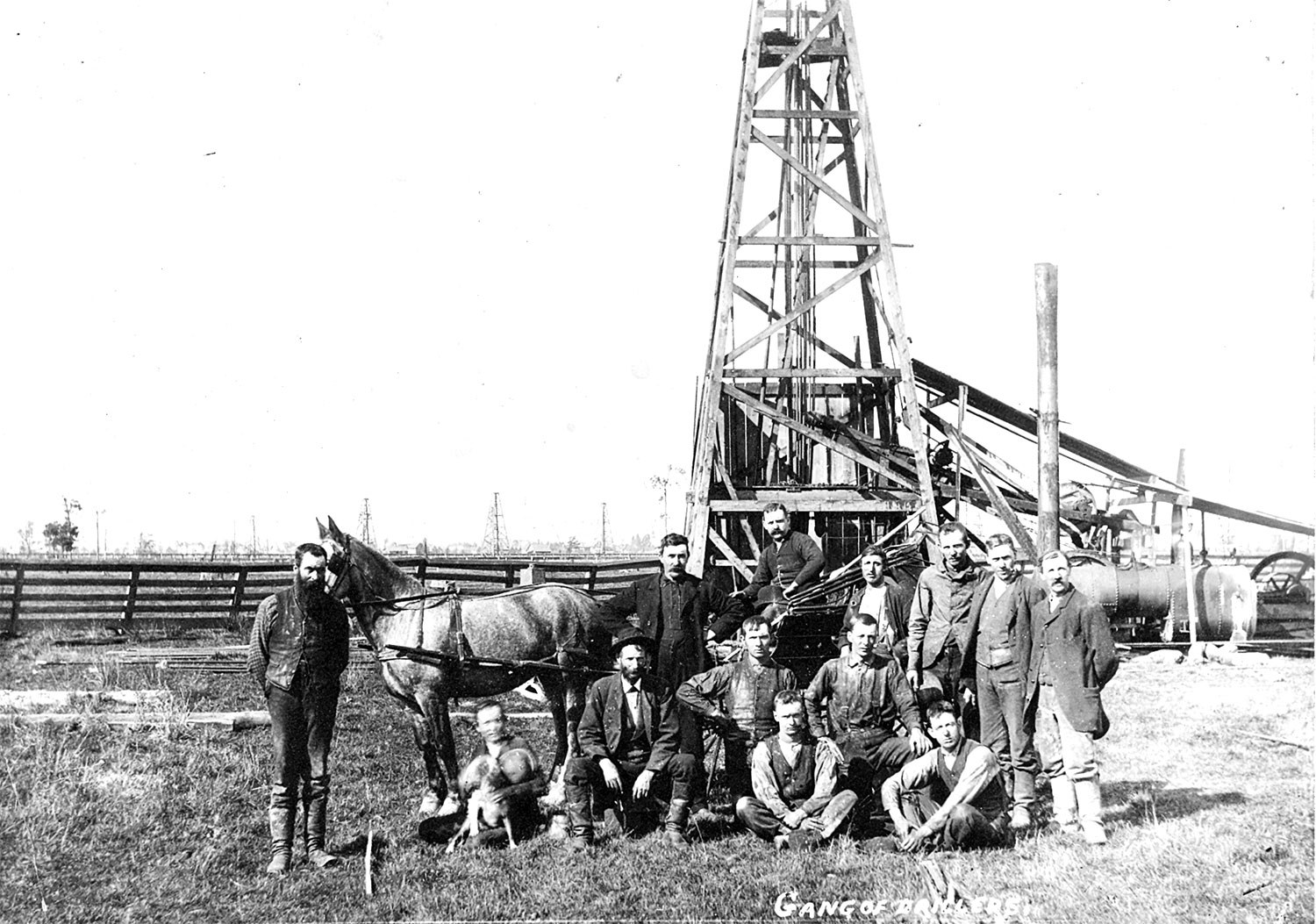

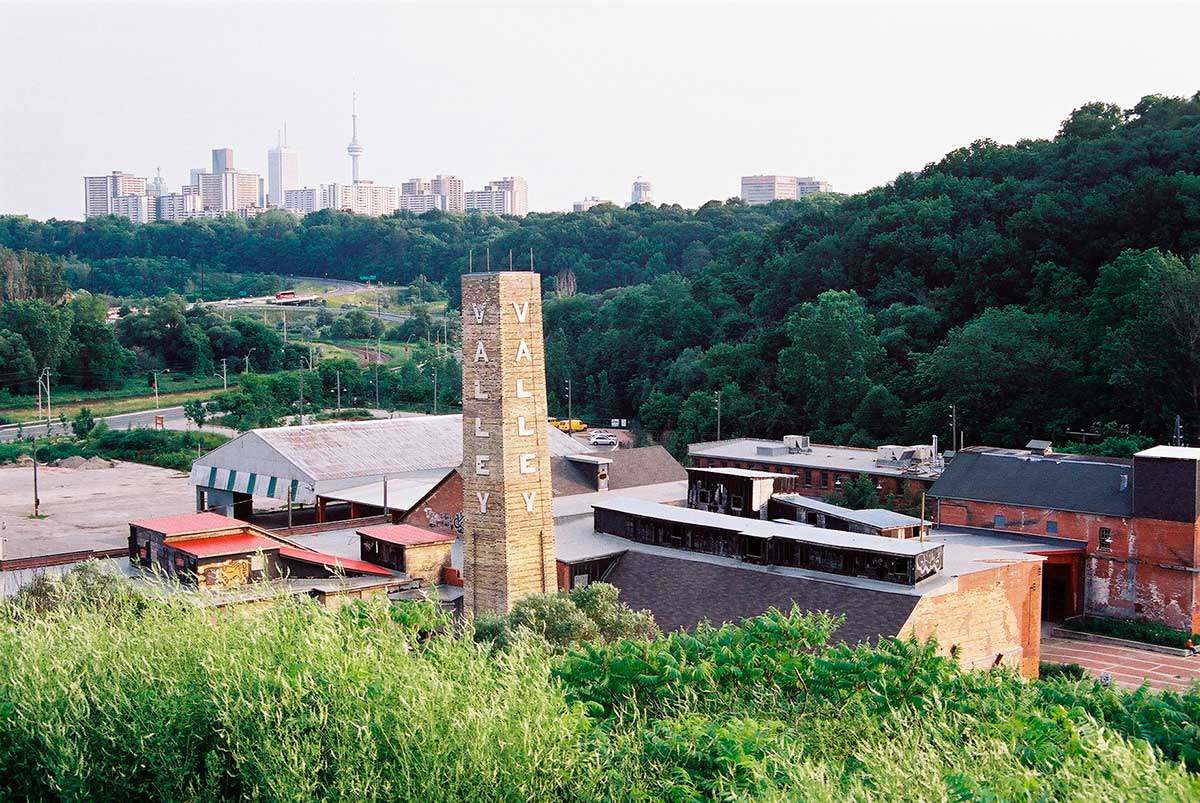

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the designation of industrial sites. One of the more interesting new districts to come into force is the Oil Heritage Area in Lambton County, recognizing its historical importance and the district’s influence on the development of the global oil industry.

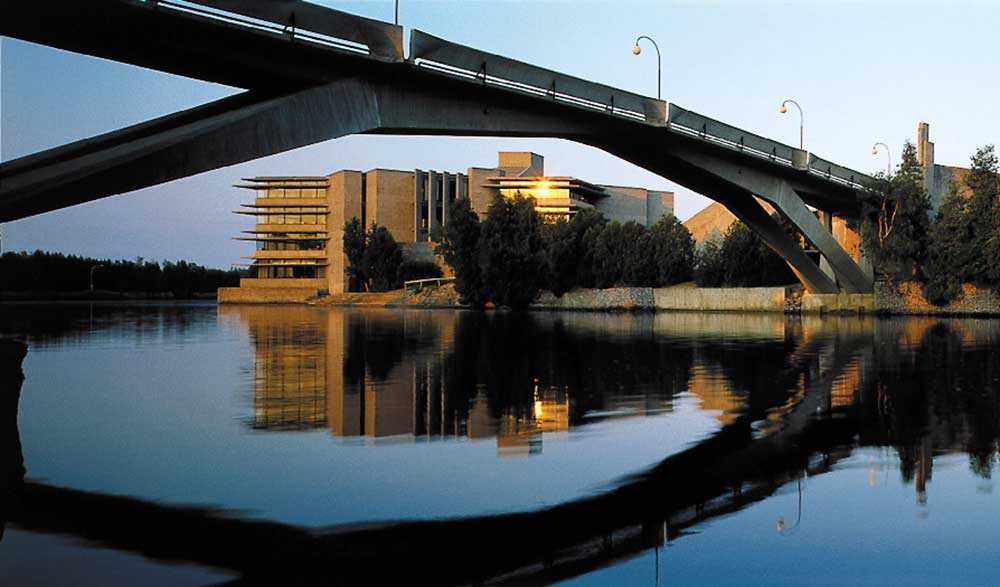

Modernist heritage areas are also being recognized as districts – the most recent example being the 2012 designation of Ottawa’s Briarcliffe neighbourhood, a 1960s-era residential enclave noted for its bold, sleek, low-profile ranch houses on heavily treed lots.

Geographically, districts tend to be most heavily clustered in Toronto and the Greater Toronto Area, followed by southwestern Ontario. A small number of districts are spread across southern Ontario, mostly along the 401 corridor between Toronto and Kingston. There is another cluster in Ottawa. Few districts, however, exist in central and eastern Ontario. Northern Ontario has one district, located in Thunder Bay (Waverley Park). Potential new districts exist in virtually every village, town and city in the province.

Since almost all heritage districts focus on multiple properties, the effort required to establish a district tends to be on a higher order of magnitude compared to an individual property designation. This fact may explain why more than 250 Ontario municipalities have passed at least one individual heritage designation bylaw, but only 39 municipalities have established one or more HCD.

The district designation process requires public consultation and engagement. It tends to run more smoothly when it starts as a grassroots effort in response to an issue that galvanizes a well established neighbourhood. A broad level of public consensus may already be established, too. The demolition of a familiar landmark, for instance, or the threat of incompatible infill development in a historical neighbourhood often triggers a call for a heritage district. Many of the districts in Toronto, for example, exist because a proactive neighbourhood group approached the city requesting designation (e.g., Cabbagetown, whose district has remained active through local stewardship).

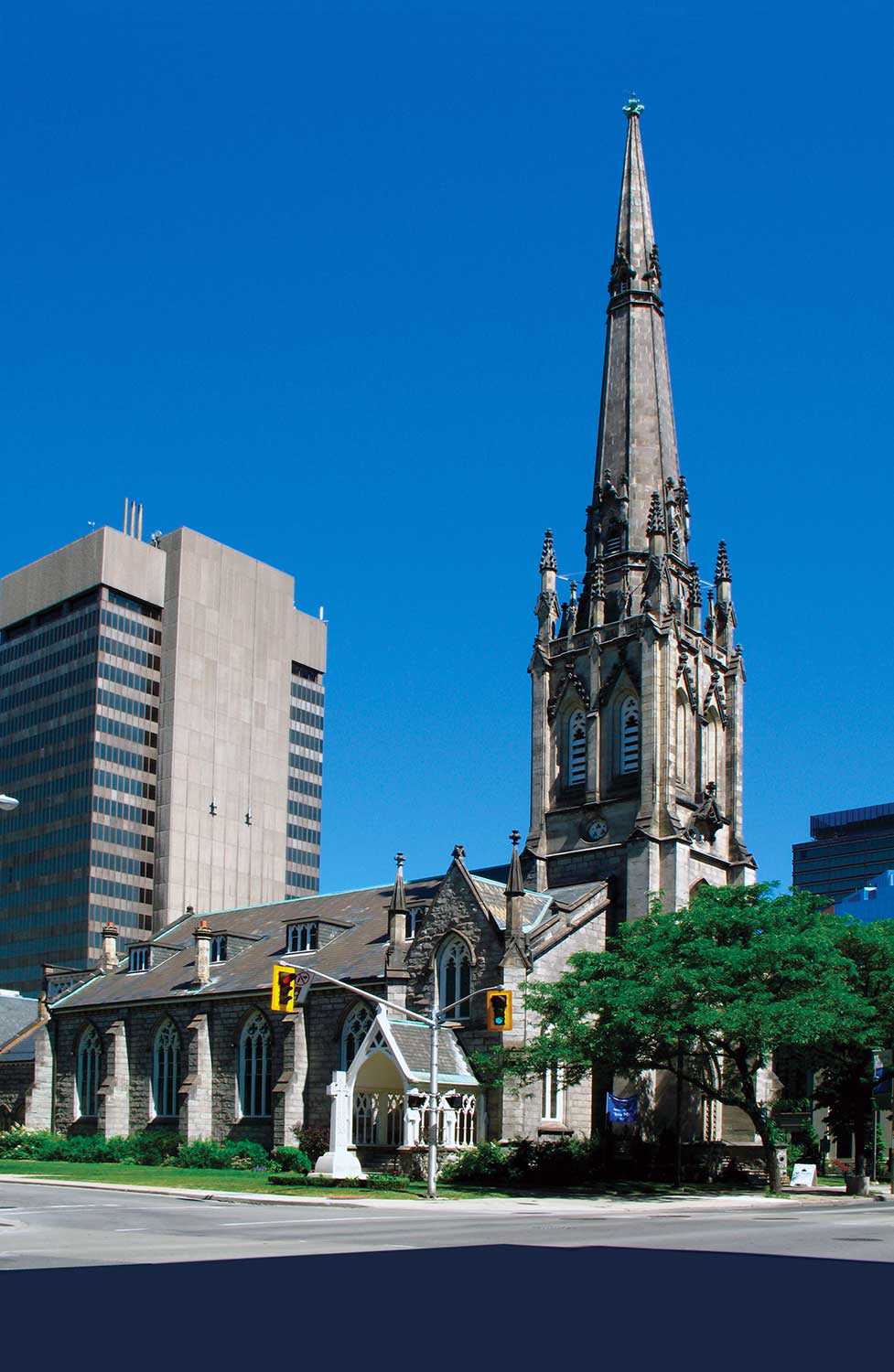

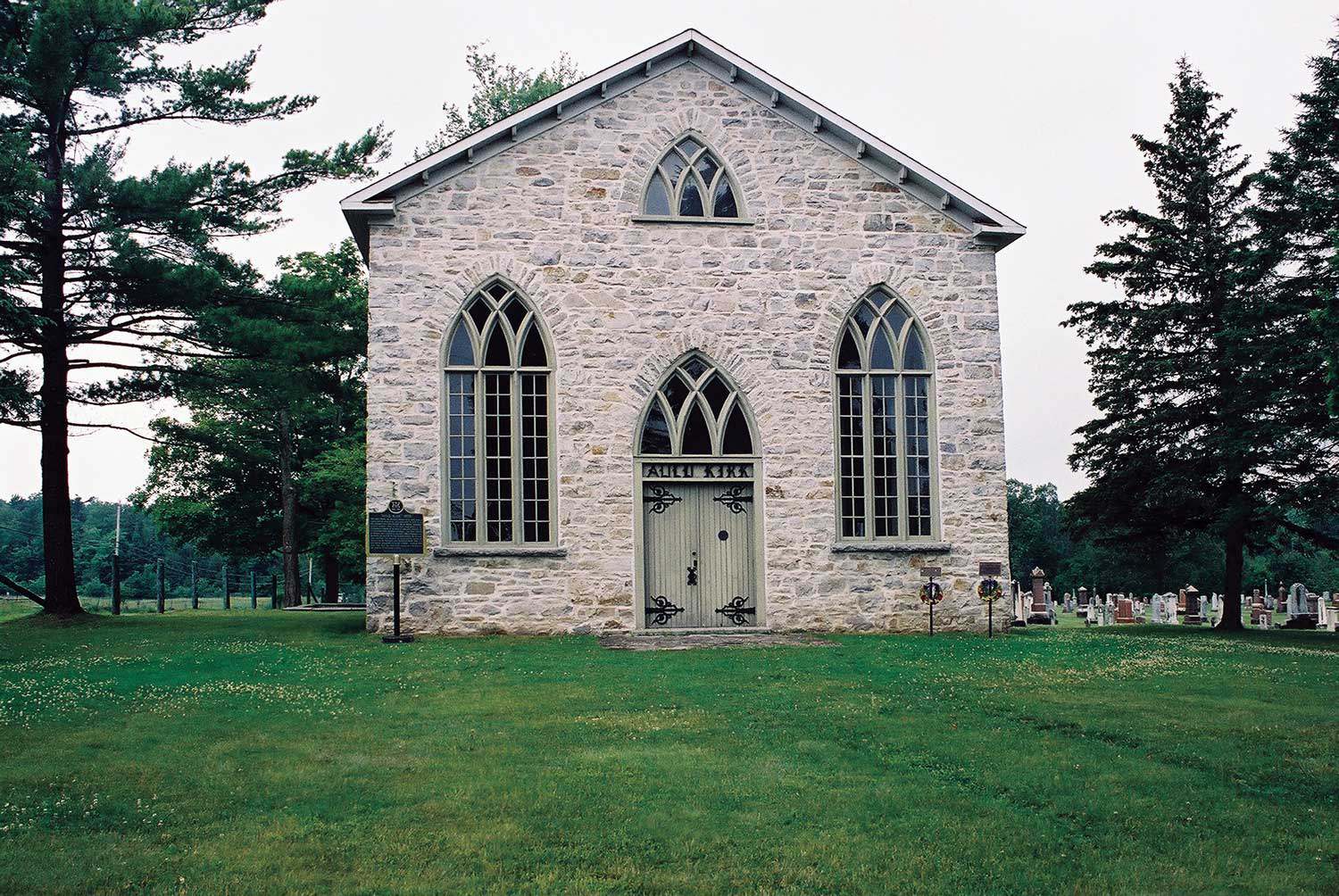

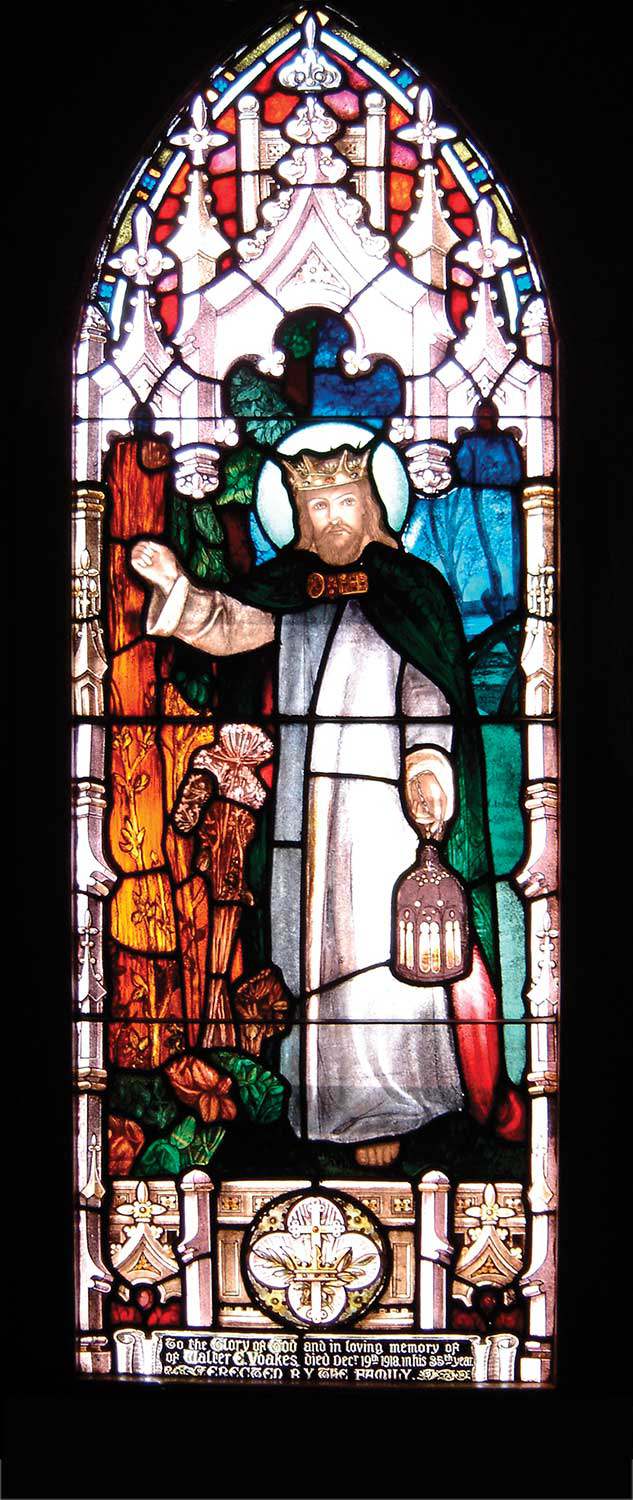

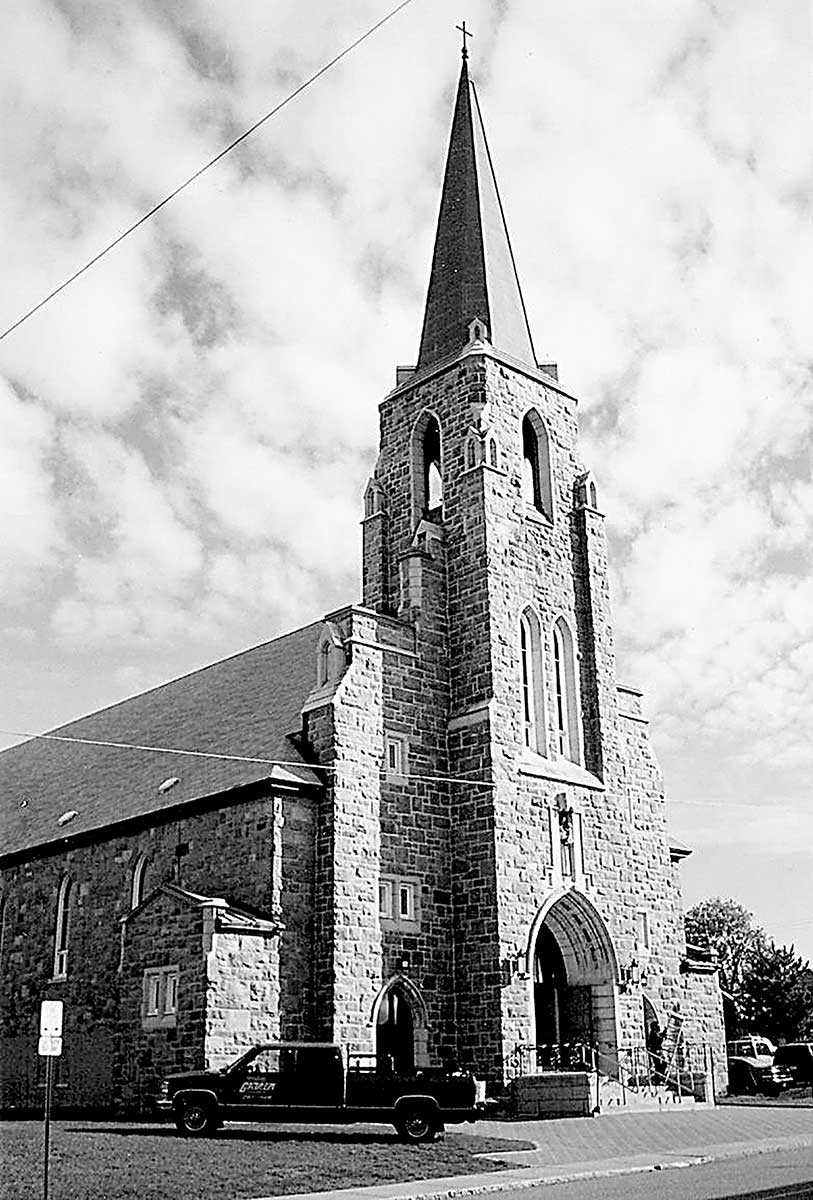

St. Mark’s United Church in Kingston, part of the Barriefield HCD. Barriefield is an example of a small rural hamlet being protected within a larger urban environment.

It is important to provide residents and property owners in a proposed district with consistent, accurate and clear communications in order to dispel any misconceptions about the implications of district designation. A district is not an urban conservation cure-all. Nor do districts have negative impacts on property values. Most significantly, districts are planning tools for managing change and not legal straitjackets designed to freeze properties in time.

Lingering misconceptions about districts tend to dissolve, however, when one considers how many districts are in place across Ontario already, not to mention the thousands of people who have lived and worked within them for decades. The best evidence supporting the merits of heritage district designation remains the districts themselves.

Fortunately, the heritage community has amassed an array of counter-arguments built on years of research, observation and reflection. Recent research compiled by the Heritage Resources Centre at the University of Waterloo on behalf of the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario refutes several myths about heritage districts.

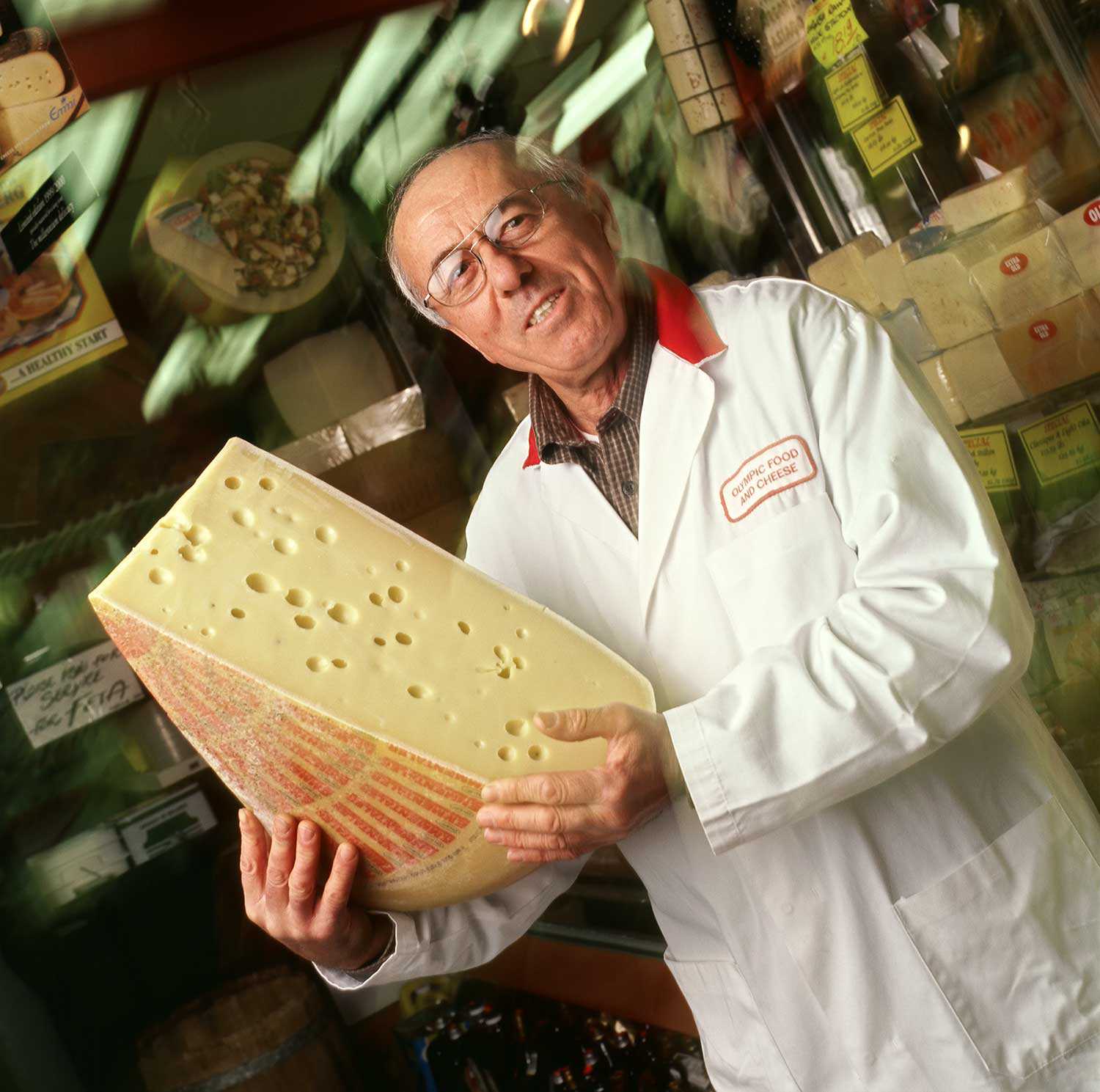

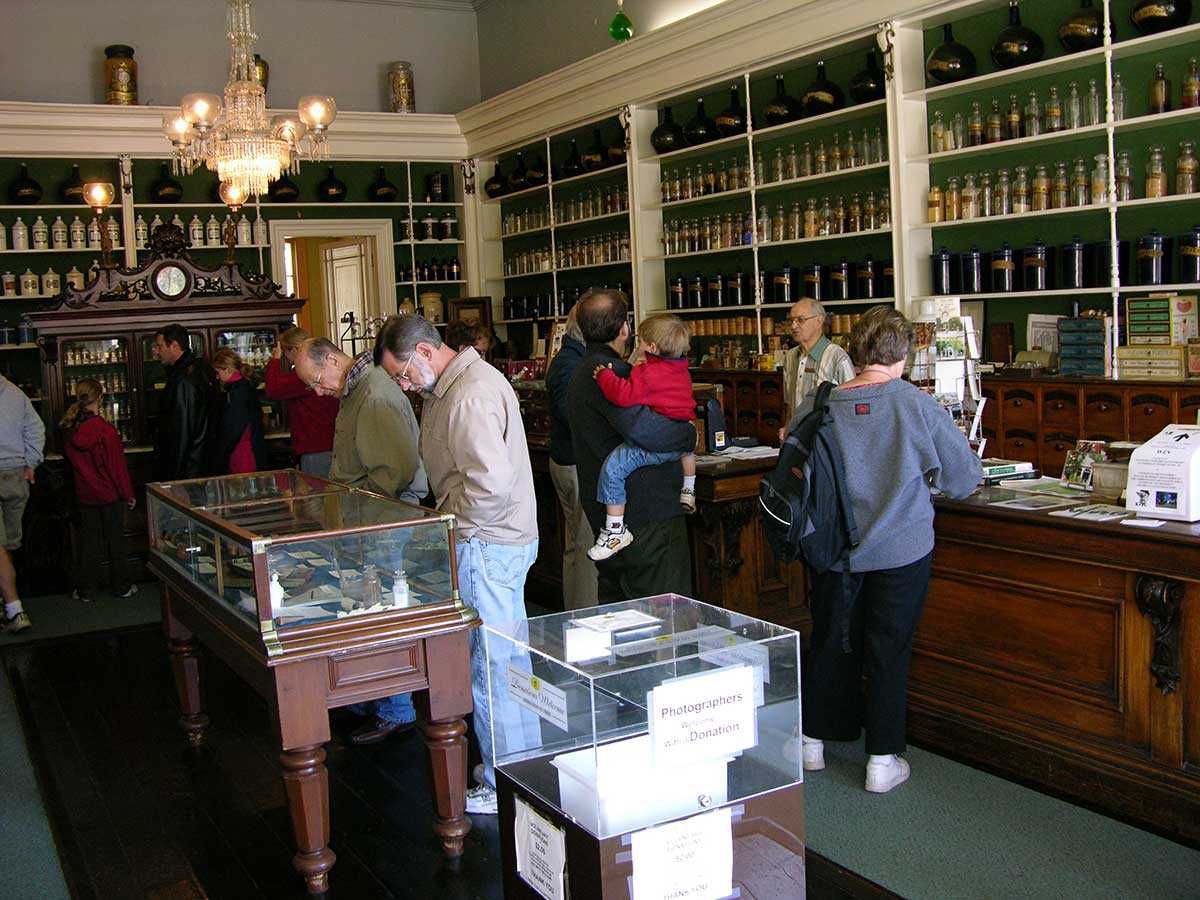

Consider the positive economic and tourism benefits of heritage districts supported by demographic data from many studies. People seek the sense of place that can be found in vibrant downtowns that possess specialty shops, antiques stores and places with ambience and authentic heritage character. Downtown heritage districts in Port Hope, Unionville, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Stratford, Perth, Cobourg, Port Perry and Kingston illustrate this potential.

OHA Register data can also shed light on some common myths. Some people believe that designation makes it impossible to alter a designated heritage building. An analysis of almost 500 heritage permits sent to the Trust by 28 different municipalities since 2010 suggests that councils, in fact, approve more heritage permits than they deny. A full 97 per cent of all heritage permits sent to the Trust were either consents or consents with conditions.

Despite their effectiveness, HCDs still face challenges – including unsympathetic infill, encroaching development, demolition by neglect or even catastrophic loss, as was demonstrated by the 2011 Goderich tornado. Any of these challenges can be made more difficult if there is no district plan, or if the plan is ineffective or outdated.

Every council decision has a tangible, cumulative impact on a district. A comprehensive and current district plan – tightly integrated within the broader land-use planning framework – helps guide, inform and manage the array of complex and unforeseen issues that can affect a district. Fortunately, the Ontario Heritage Act includes mechanisms to adopt new plans where none previously existed, or to amend old plans to meet current standards.

Local decision-makers seem to recognize that heritage districts contribute to sound municipal planning and support vibrant, stable communities. A casual stroll or a drive through any of Ontario’s districts vividly demonstrates this point. Most property owners see the merits, too, recognizing that coordinated heritage guidelines and policies benefit their properties.

It should be no surprise that over the past decade, more heritage conservation districts have come into force than in the previous 25 years. Heritage conservation districts may very well be the province’s most popular – and powerful – tool in our heritage toolkit.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)