Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Adapting today’s places of worship

Buildings and architecture, Adaptive reuse

Published Date: Sep 10, 2009

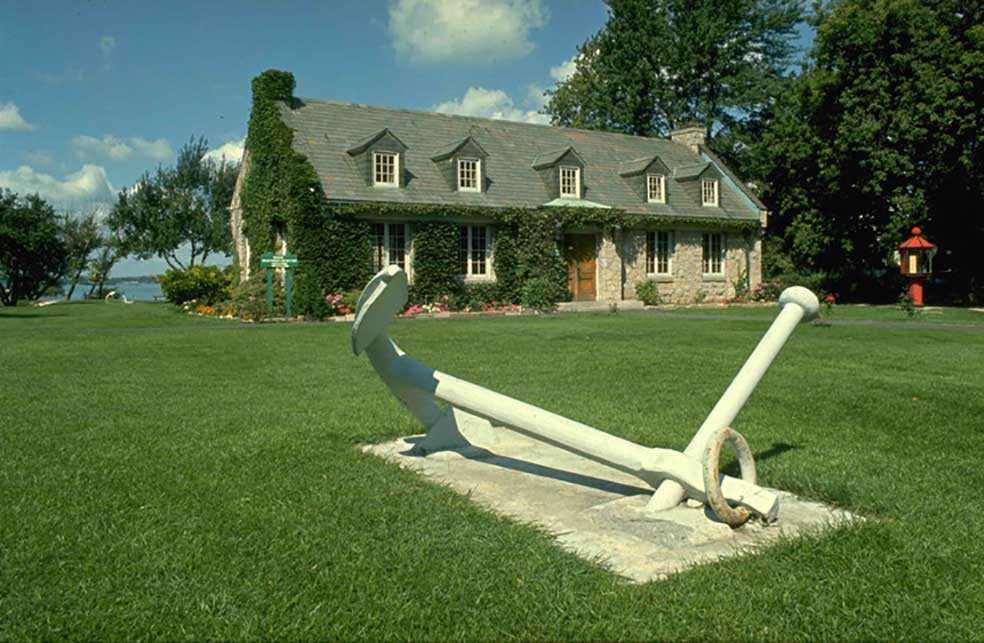

Photo: Third-floor unit, Glebe Lofts, Toronto

Adaptive reuse of religious buildings can simultaneously preserve significant heritage sites and benefit communities, but in Ontario those who want to make these conversions face political, social and architectural hurdles. With determination and a thoughtful approach, however, they can succeed – as the following case studies demonstrate.

The Glebe Lofts

Formerly: Riverdale Presbyterian Church

Address: 662 Pape Avenue, Toronto

Built: 1912, with a major addition in 1920

Adapted: 1999

Combining religious use and urban housing

Development pressure in urban areas is fuelling the transformation of underutilized and vacant churches into multi-unit residential buildings. This type of conversion, ranging from affordable housing to upscale condos, preserves local landmarks, enhances the streetscape and increases urban density. Builder-developer Robert Mitchell converted the former Riverdale Presbyterian Church in Toronto into the Glebe Lofts. Condominiums occupy the south nave, while the north end remains an active church.

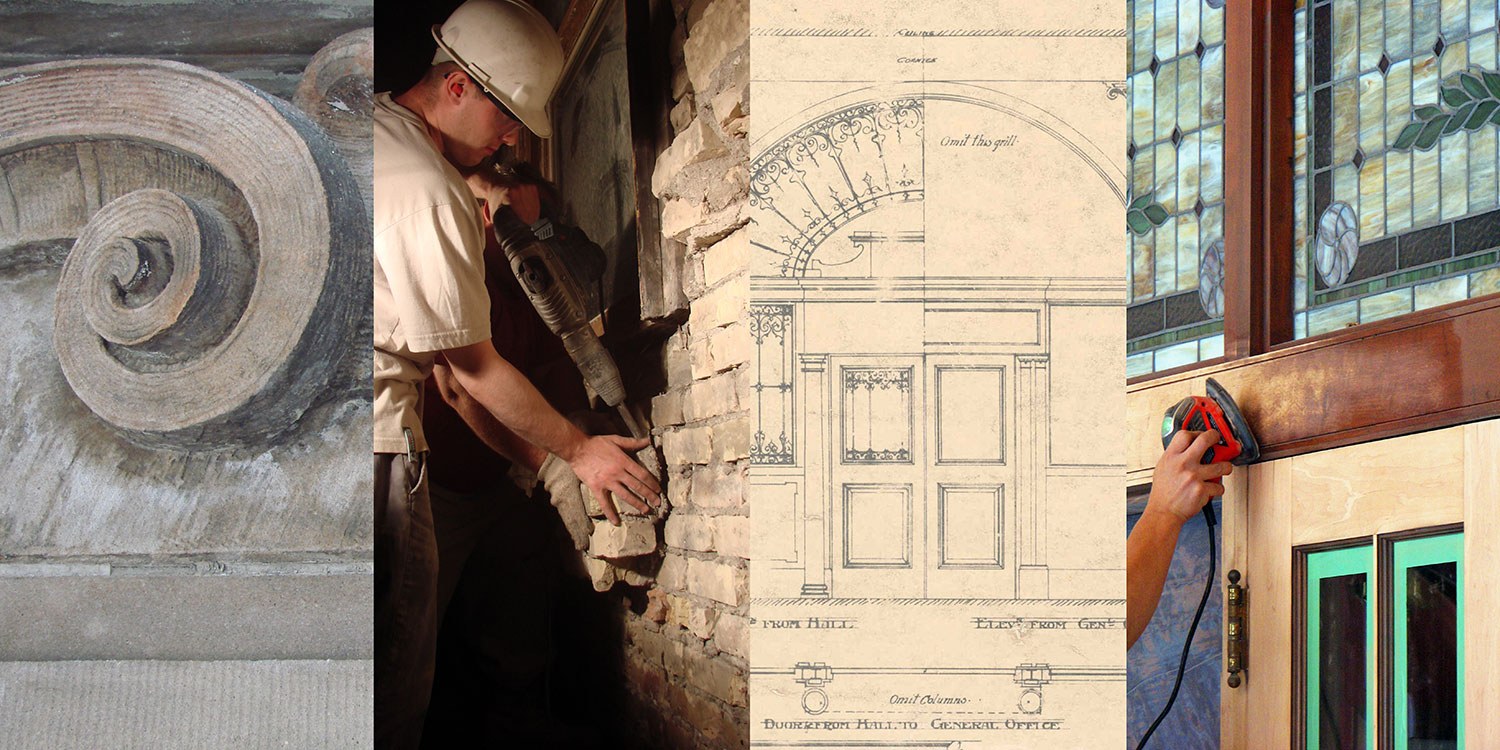

Built in 1920, the Gothic revival building featured high ceilings and exposed steel trusses. Mitchell explains that his design was effectively dictated by the building’s original proportions: “The first thing I look at is the distance between the footings. From this I can estimate whether or not excavation for underground parking is feasible.” In the third-storey loft unit, the steel trusses remain exposed, providing visual interest and reminding us of the building’s original function. While that use has changed, the units benefit from the church’s spatial qualities.

The Glebe Lofts took about two and a half years to complete. Conversions in urban areas are often challenging due to the complexity of the planning approvals required. Consequently, Mitchell chooses his projects carefully. He also understands the importance of careful pre-design structural analysis. The success of 662 Pape shows that a community’s architectural heritage has market appeal, and that religious use can co-exist with residential redevelopment.

Green Door Bed and Breakfast

Formerly: Brockville Pentecostal Tabernacle

Address: 61 Buell Street, Brockville

Built: 1928

Adapted: 2005

Regeneration of an art deco classic

The Brockville skyline is graced by steeples and towers that mark the churches of various Christian denominations whose United Empire Loyalist roots extend back to the late 18th century. As in many cities, some historic buildings in Brockville became underutilized as the city’s population and businesses moved out of the core. This situation, however, presented Lynne and Peter Meleg with the opportunity, in 2005, to acquire the vacant Brockville Pentecostal Tabernacle. With considerable “sweat equity,” they carefully transformed it into the Green Door Bed and Breakfast.

“We wanted to do a bed and breakfast for a while, and when we came across the building we just had to have it,” Lynne explains. “We were enamoured with the building, which was a very sound structure with no interior supporting walls, ideal for what we had in mind.” Pointing to the location of the former stage, Peter adds, “We thought the stage was a unique feature of the building, and we managed to figure out a way to keep it.” The couple transformed the stage into a library, now the focal point of the interior, and used art deco revival décor to augment the former tabernacle’s 1920s character.

Fortunately, when the Melegs acquired the building, it was in sound structural condition, possessing a completely open floor plan and a modest scale. These attributes and its location – within walking district of the city’s commercial core – made their project not only possible, but highly successful.

Glebe Community Centre

Formerly: St. Paul’s Methodist Church

Address: 175 Third Avenue, Ottawa

Built: 1914-24

Adapted: 1972-74 and 2004

Preserving a community hub’s “spirit”

A large dome rising above Ottawa’s Glebe neighbourhood marks an excellent example of adaptive reuse. St. Paul’s Methodist Church – later St. James United Church and now the Glebe Community Centre – was originally designed by Colonel Clarence J. Burritt in the Palladian Revival style. “The building has a monumental copper dome, and is a landmark in a city where domed buildings are rare,” says Ian McKrecher, Glebe community heritage leader. By the 1960s, the size of the church’s congregation had declined and the property was sold to the City of Ottawa, which retained the building as a community centre, making only minor interior alterations. Through the activitism of the Glebe Community Association, which had long been vocal about the building’s importance to the neighbourhood, major renovations were eventually made to it under the direction of local architect Barry J. Hobin & Associates.

The central space was not subdivided, as sometimes happens with large-volume interiors, but preserved, allowing for flexibility of use and a cost-effective conversion. The original stepped floor was removed, but replaced with patterned hardwood that mirrors the dome’s ceiling.

By reusing the former church, the community has benefited from the building’s convenient location, distinctive architecture and utility as a community centre. Stuart Lazear, Heritage Planner at the City of Ottawa, describes it as “a community focal point and landmark for cultural and recreational activities in the Glebe neighbourhood.” The Glebe Community Centre’s successful conversion demonstrates the wisdom of simplicity and minimal intervention in preserving a heritage building of significant character.

Vogan Residence

Formerly: Wesleyan Methodist Church

Address: 332 Kettleby Road, Kettleby (King Township)

Built: 1873

Adapted: 1966

Creating a home in a former church

The Vogan home at 332 Kettleby Road is not a typical house – it occupies the village of Kettleby’s former Wesleyan Methodist church. Wesleyan Methodist became a United Church in 1925 and continued in religious use until the mid-1960s, when it was sold and became a private residence.

Gary Vogan, the present owner, notes that “the church was not designed to live in,” as the original space did not have plumbing, electricity or storage. Introducing these elements to a building can be challenging.

Other changes were made to facilitate occupancy. Rooms and a mezzanine were framed with beams salvaged from an old barn. When the original foyer was replaced, the Vogans discovered that the building code required that the piping run vertically. This stipulation led to the construction of a full fireplace that contains all of the services. Although the changes were functional, they did not detract from the interior’s original quality. The front room of the home remains open-concept, enabling the Vogans to display their extensive collection of Canadiana.

Both exterior and interior adaptations were contextual in their execution, enhancing Kettleby’s vernacular architecture. Modest, they also demonstrate the value of “contained” alterations to neighbourhood heritage. Part of the Vogans’ success is that they took an additive and reversible approach to converting this unheated country church, working within the building envelope to keep costs down and to preserve the building’s scale.

Church Restaurant

Formerly: Mackenzie Memorial Gospel Church

Address: 70 Brunswick Street, Stratford

Built: 1873-74

Adapted: 1975

Offering fine dining in an inspirational setting

The former Mackenzie Memorial Gospel Church in Stratford occupies an ideal location, only a short walk from the town’s famous theatres. This location, and the building’s attractive interior architectural features, inspired its transformation into the Church Restaurant.

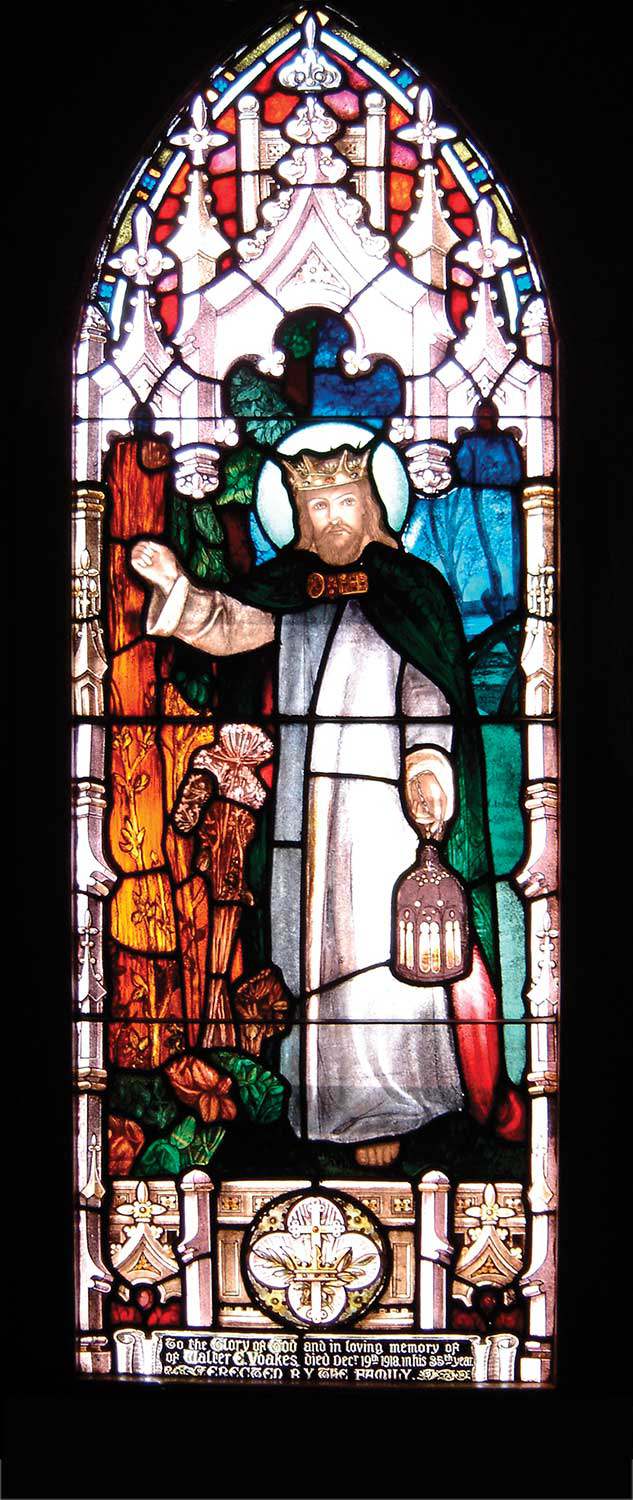

Owner Mark Craft believes that the original building’s structural integrity was instrumental in the success of this difficult conversion. The largest architectural alteration was the introduction of a commercial kitchen into a former crawl space. Some original footings remain intact in an area of the crawl space that now houses the restaurant’s wine cellar. The pews were used to create seating platforms around the dining area’s perimeter. Also adorning the interior are original light fixtures and stained-glass windows. The restaurant’s dark wood furniture harmonizes with the wooden trusses, which retain their Victorian finish.

The alterations appropriately balance the restaurant’s needs with the building’s original character. The open volume and finishes have been preserved, while respecting the private-public divisions and natural servicing opportunities inherent in the church plan. The dramatic restaurant interior perfectly complements the Stratford theatre experience. Although the transformation occurred over 30 years ago, the Church Restaurant and its upstairs sister restaurant, the Belfry, remain one of Ontario’s best examples of the conversion of a historic property into a hospitality venue.

St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church

Formerly: Holy Blossom Temple

Address: 115 Bond Street, Toronto

Built: 1897

Adapted: 1937

Adapting one faith’s building for another faith

Located in the heart of Toronto, St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church remains one of very few examples of Byzantine inspired architecture in the city. Built as Holy Blossom Temple, a Jewish synagogue, the building was originally designed by Canadian architect John Siddall. In the early part of the 20th century, its façade was adorned with two large onion-shaped domes atop two large towers, as well as several smaller onion domes along the central frontispiece. Due to the rapid growth of its congregation in the 1930s, Holy Blossom relocated to a new building (at 1950 Bathurst Street, Toronto), and its former home was sold and converted into this Greek Orthodox church.

The most notable exterior change was the replacement of the original onion domes with a hemispherical dome inspired by Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. The drum of the central dome was altered again in the 1980s to feature a stained-glass clerestory. Around the same time, the façade’s central tympanum was refitted with a mosaic painted by celebrated Italian mosaicist Sirio Tonelli and the traditional iconography in the church’s interior was painted by Pacomaioi monks from Mount Athos in Greece.

The successful conversion of Holy Blossom Temple to St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church demonstrates that faith-to-faith building conversions are often an easy fit. It also reminds us of the practical origins of adaptive reuse. We consider the adaptation of religious buildings a new trend, but the spirit of reusing and recycling them has always been part of our religious heritage.