Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

- Home

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

Expanding the narrative

This is part of a broader conversation about whose history is being told, about gender, people of colour and the economically disenfranchised, and others whose stories have been overlooked or intentionally omitted from the authorized discussion.

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

Intangible heritage

Intangible cultural heritage includes language, traditions, music, food, special skills, etc.

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Sacred landscapes in Ontario’s communities

While places of worship are a visible aspect of Ontario’s heritage, they are part of wider cultural landscapes that can include supporting structures, burial places, view planes, archaeological resources and landscape features. Sites of spiritual significance to First Nations are also cultural landscapes. All of these landscapes promote a broader understanding of not only particular faiths, but also community development and identity. They have multiple, overlapping meanings, and constitute an important part of Ontario’s history.

The term “cultural landscape” is complex and has been used in different ways. Geographer James Duncan wrote that a landscape can be understood as “the appearance of an area, the assemblage of objects used to produce that appearance, and the area itself.” Religious communities use landscapes to express their beliefs in physical form. As a result, understanding and protecting Ontario’s religious and spiritual heritage require a holistic approach.

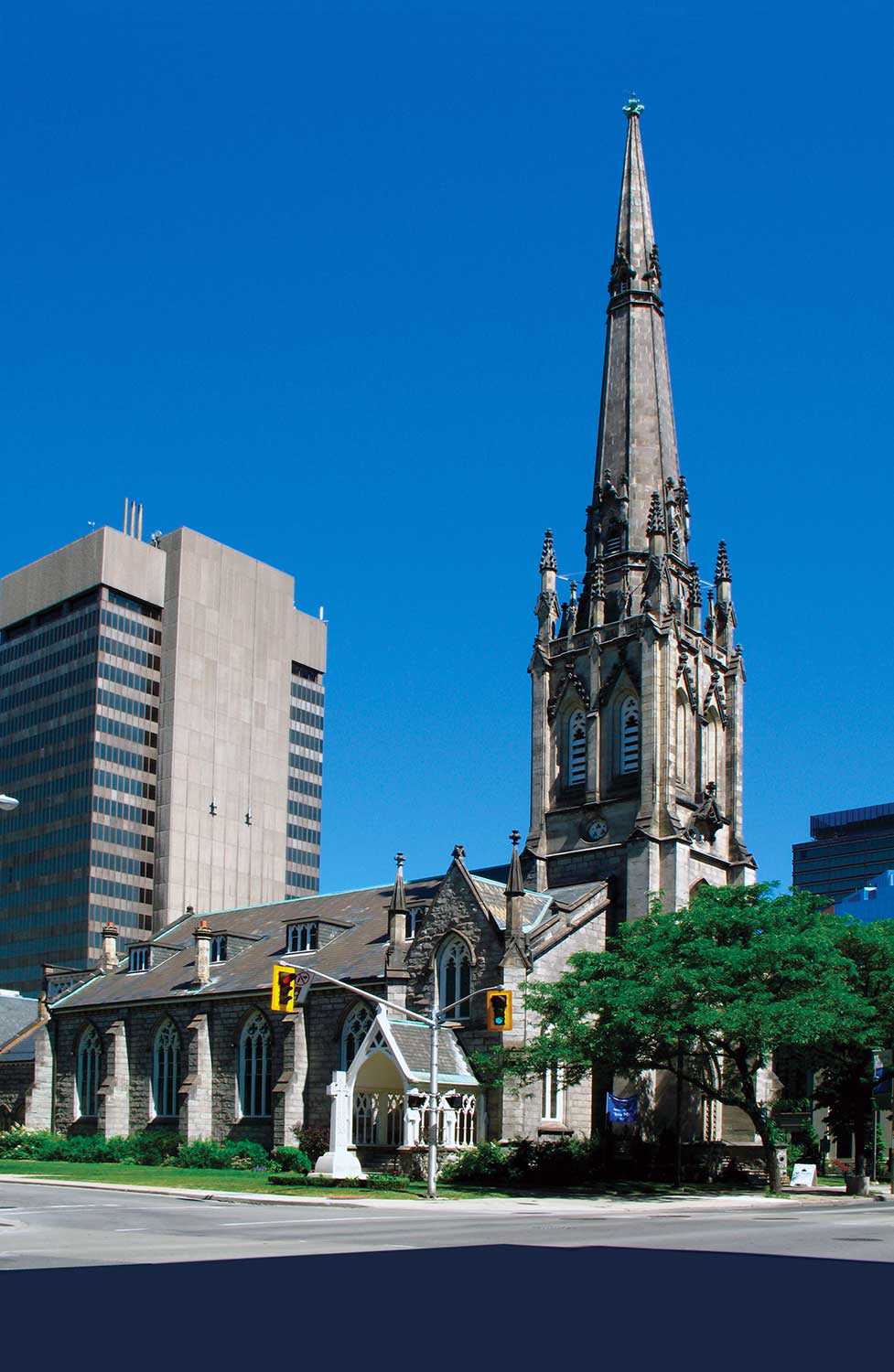

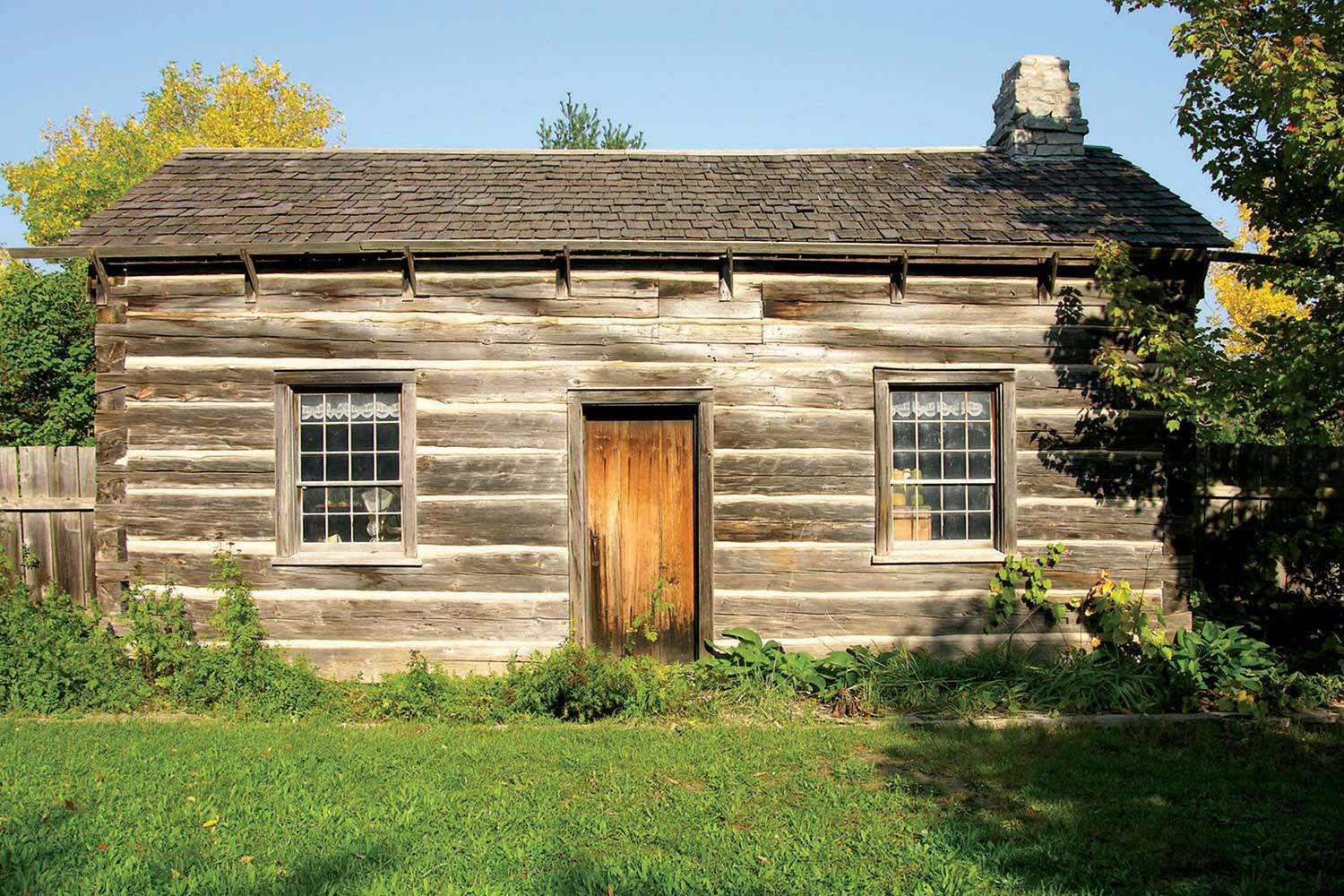

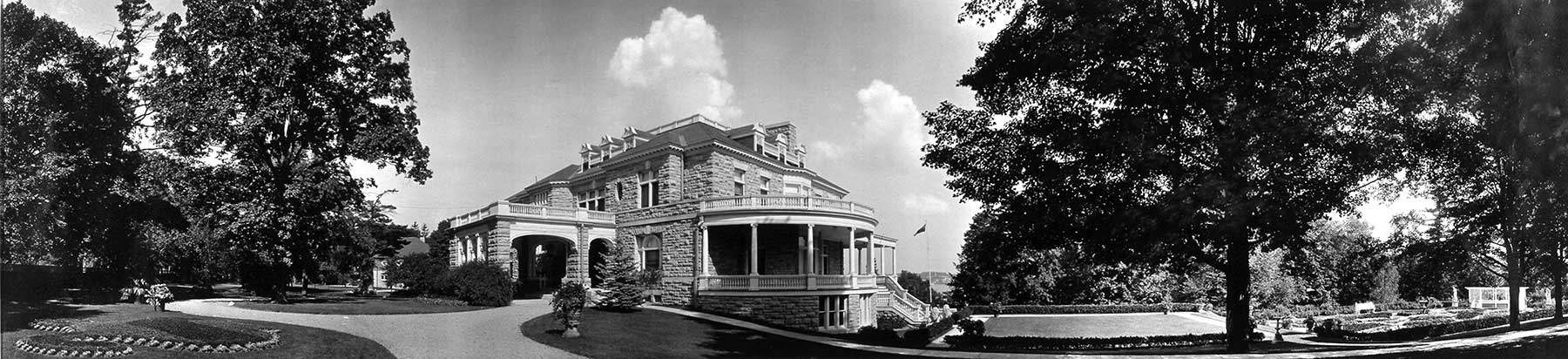

Religious and spiritual landscapes serve as focal points for many Ontario communities. Churches and their supporting structures were among the earliest constructions in new settlements, and some churches were highly visible local landmarks. Belief systems were expressed through rectories and manses, meeting halls, drive sheds, religious statues and monuments, religious schools, chapels, landscaping and burial grounds.

Many of these landscapes survive in concentrated form. The grounds of St. George’s Cathedral in Kingston include the cathedral, the church hall, Lord Sydenham’s grave and careful landscaping, including green space. The fence posts are marked by miniature bishops’ caps. Nearby are the church office and lower burial ground. In other cases, the interrelated parts of the landscape are spread out. In Minden Hills, the clergy house for St. Paul’s Anglican Church sits across the Gull River from the church. Places of worship that are no longer used as such still remind us of the larger landscape they once represented – for example, a former Quaker meeting house in Kingston, now a private residence.

First Nations’ spiritual landscapes – such as Serpent Mounds Provincial Park, the Mnjikaning Fish Weirs and Petroglyphs Provincial Park – play an integral part in Ontario’s history. These sites, central to First Nations’ identities and beliefs, should be considered living landscapes.

Many tools exist to protect the province’s religious and spiritual cultural landscapes, including the Planning Act (with its associated Provincial Policy Statement) and the Ontario Heritage Act. To ensure that these landscapes are protected, they must first be identified and community leaders must understand their importance. Initiatives such as Save Our Sanctuaries in Lakeshore indicate how important these landscapes are to our citizens. Many of these sites are dynamic – still occupied and being modified – and appropriately managing change should be a priority. These are among the challenges and opportunities facing supporters of Ontario’s past and its future.

RelatedStories

- 05 Feb 2026

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Elizabeth Papadopoulos,

Adaptive reuse: Building on an architect’s perspective

Ontario Heritage Trust architect, Leroy Shum, on the key elements of adaptive reuse, emerging industry trends and the possibilities of what it all means. What...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: David Leonard,

How Doors Open Ontario activates the province’s communities

The Ontario Heritage Trust’s Doors Open Ontario program works with communities and partners to open the doors, gates and courtyards of Ontario’s most unique and...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Romas Bubelis,

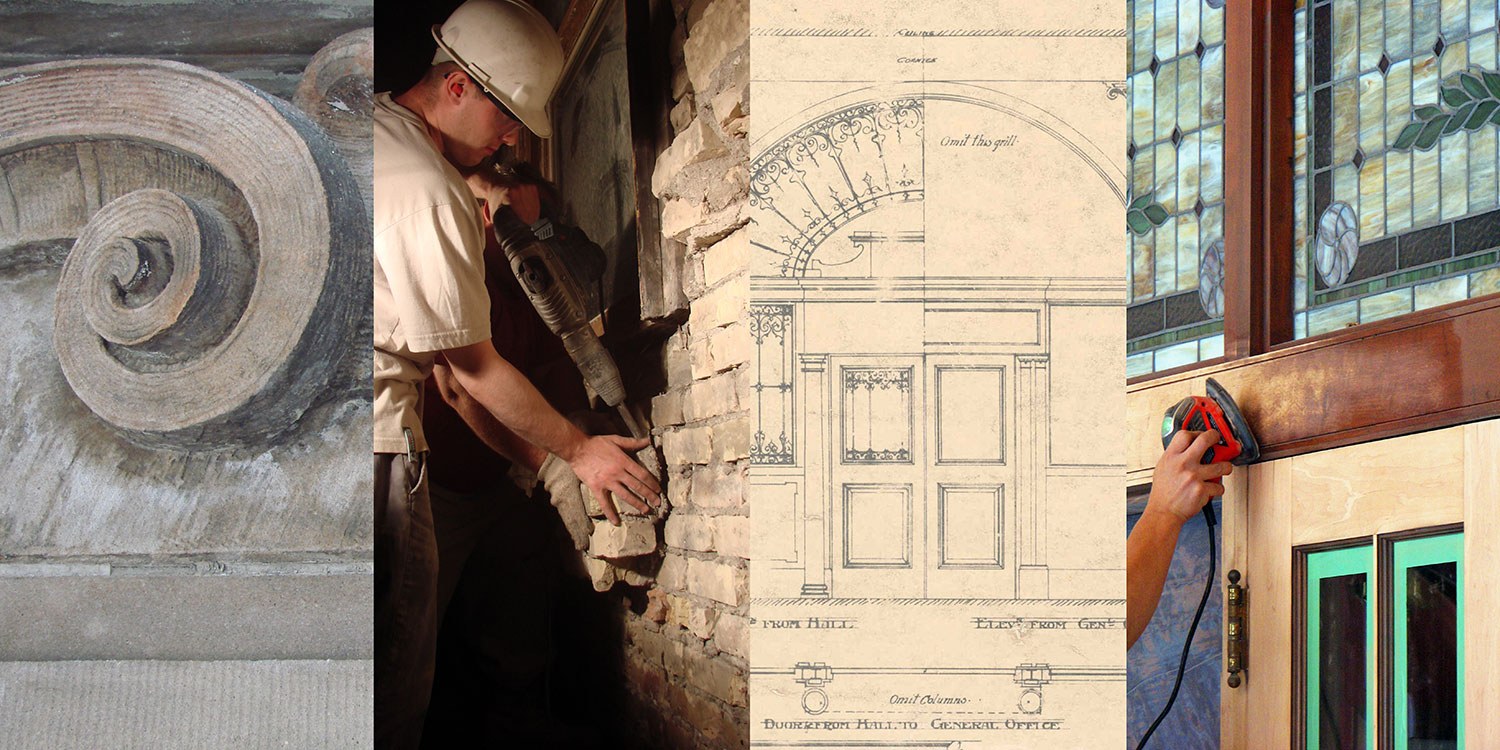

The case for craftsmanship

One of the greater pleasures of working in architectural conservation in Ontario is the opportunity it provides to work with traditional building materials: the timber...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Christina Jennings,

Quiet on the set

Shaftesbury is the company behind the hit television series Murdoch Mysteries and Frankie Drake Mysteries, both of which air on CBC in Canada and are...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Emily Sajdak,

The economic halo effect of sacred places: Measuring civic impact in an innovative new way

Nestled in the old city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Old St. George’s United Methodist Church is a “mother church” of the denomination and the oldest Methodist...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Erin Semande,

Case study: Brockville Railway Tunnel

Location: 1 Block House Island Road, BrockvilleOwner: City of BrockvillePartners: Brockville Railway Tunnel Committee (plus countless generous donors)Original use: Canada’s first railway tunnel and part...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Food

Adaptive reuse - Author: Erin Semande,

Case study: Mudtown Station Brewery and Restaurant (Owen Sound)

Location: 1198 1st Avenue East, Owen SoundOwner: City of Owen SoundPartners: Kloeze Family (Mudtown Station Inc.)Original use: Passenger train station (Owen Sound Canadian Pacific Railway...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: John Coleman,

Learning from the past

Heritage has always been at the heart of the University of Windsor’s ambitious plan to preserve the century-old Windsor Armouries and transform the building into...

Museums and heritage: Building livable communities through soft power

Museums and heritage are engines of urban redesign and revitalization. Lord Cultural Resources has worked in 450 cities worldwide on some 2,600 museums, cultural plans...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Michael Emory,

Heritage buildings and the evolution of workspace

I work for Allied Properties – a leading owner, manager and developer of urban workspace in major Canadian cities. Allied’s units are publicly traded on...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Kiki Aravopoulos,

Case study: Thunder Bay District Courthouse

Location: 277 Camelot Street, Thunder BayOwner: David Sun, Business owner/InvestorPartners: Ascend HotelsOriginal use: CourthouseCurrent use: Hotel The former Thunder Bay District Courthouse sits perched atop...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Jennifer Campbell,

Heritage builds vibrant communities and cultural economies in Kingston

In 2010, the City of Kingston released its first Culture Plan – a document that shared a sustainable, authentic, longterm vision for cultural vitality in...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Paul Shaker,

The economic value of heritage districts: How assessment growth in heritage conservation districts compares with non-designated areas in Hamilton

There are competing views about the value of heritage properties. On the one hand, there is a growing consensus on the esthetic and economic development...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Environment

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Clare Ronan,

Reside: When heritage preservation translates to affordable housing

Raising the Roof is a Canadian charity that provides national leadership in homelessness prevention through various initiatives. Reside is one such project that creates affordable...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Thompson M. Mayes,

Old places support a sound, sustainable and vibrant economy

In Why Old Places Matter, I wrote about the many reasons that old places help people flourish. Yet, I intentionally saved the discussion of how...

- 01 Oct 2019

- Economics of heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Beth Hanna,

Revitalizing communities – The power of conservation

Over the past few years, I’ve spoken and written extensively about value – exploring questions of what we protect, how we make those decisions, and...

- 17 Feb 2017

- Buildings and architecture

MyOntario - Author: Kevin Mannara,

What was and what will be

The term symbolkirchen can roughly be translated as a “symbol bearing church.” Such churches point to living realities beyond ourselves and hold the potential to...

- 17 Feb 2017

- Buildings and architecture

MyOntario - Author: Georges Quirion,

Ontario’s rich industrial history

Northern Ontario has unique structures, not familiar to many, spread out through small northern communities, reflecting its rich history and its vast wealth of precious...

- 17 Feb 2017

- Indigenous heritage

Buildings and architecture

MyOntario - Author: R. Donald Maracle,

Christ Church, Her Majesty’s Chapel Royal of the Mohawk – Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory

During the American Revolution, the Mohawks were forced to flee their homeland in upper New York State. In 1784, after spending several years in Lachine...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Matthew Somerville,

The changing landscape of farming

Growing up on a small family farm, I have witnessed the benefit and impact of technology on agricultural landscapes. In the 1980s, our barn was...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Paul General,

I’m not hunting on your farm … you’re farming on my hunting territory

My people – the Haudenosaunee – have been part of the land along the Grand River for millennia, while other cultures have been here since...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Wendy Shearer,

Reading the landscape

An important value of learning to observe and understand the cultural landscape is to see how natural features and processes have been modified or enhanced...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Christopher Andreae,

Industrial cultural landscapes: Fragile and fugitive

Appreciating industrial cultural landscapes can be challenging due to the diversity of industrial activities and locations. The variation between rural and urban landscapes described below...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Gerald Hill,

Where is who we are

What might I mean by landscape holds us? When we open our eyes, we see light. We open our mouths, we breathe air. These are...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Beth Hanna,

The cultural landscape – A framework for conservation

Heritage conservation is not about the past. It’s about the places that surround us and the diversity of our communities. It’s about ensuring that the...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Anthony Chegahno,

Nochemowenaing: You don’t need to walk through here (An interview with Anthony Chegahno)

The Ontario Heritage Trust and the Chippewas of Nawash unceded First Nation co-steward lands in northern Bruce Peninsula that are part of an Indigenous cultural...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Lisa Prosper,

Cultural landscapes: Challenges and new directions

Cultural landscapes were first introduced into the heritage lexicon in the early 1990s as a new type of cultural heritage resource. The typology was a...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Bob Sutherland,

Reconnecting with Cree culture, language and land: An interview with Bob Sutherland

On July 20, 2016, Sean Fraser from the Ontario Heritage Trust interviewed Bob Sutherland about his experiences and travels reconnecting with Cree relations in the...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Thomas Wicks,

Tools for conserving cultural landscapes

Landscapes may appear static but they are always changing. Whether by human or natural influences, the changes are constant and often important. So, how do...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Sean Fraser,

Scotsdale Farm – An experience of interwoven landscapes

Dust stirs up behind the car, shaken by the audible crunch of rubber on gravel as we drive slowly along the fenced laneway leading east...

- 09 Sep 2016

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Mike Fedyk,

Cultural landscapes, the Métis way of life and traditional knowledge

While the term cultural landscape is not commonly used when discussing Métis land use, it is a concept that Dr. Brian Tucker, who holds a...

- 05 Dec 2014

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Valerie Verity,

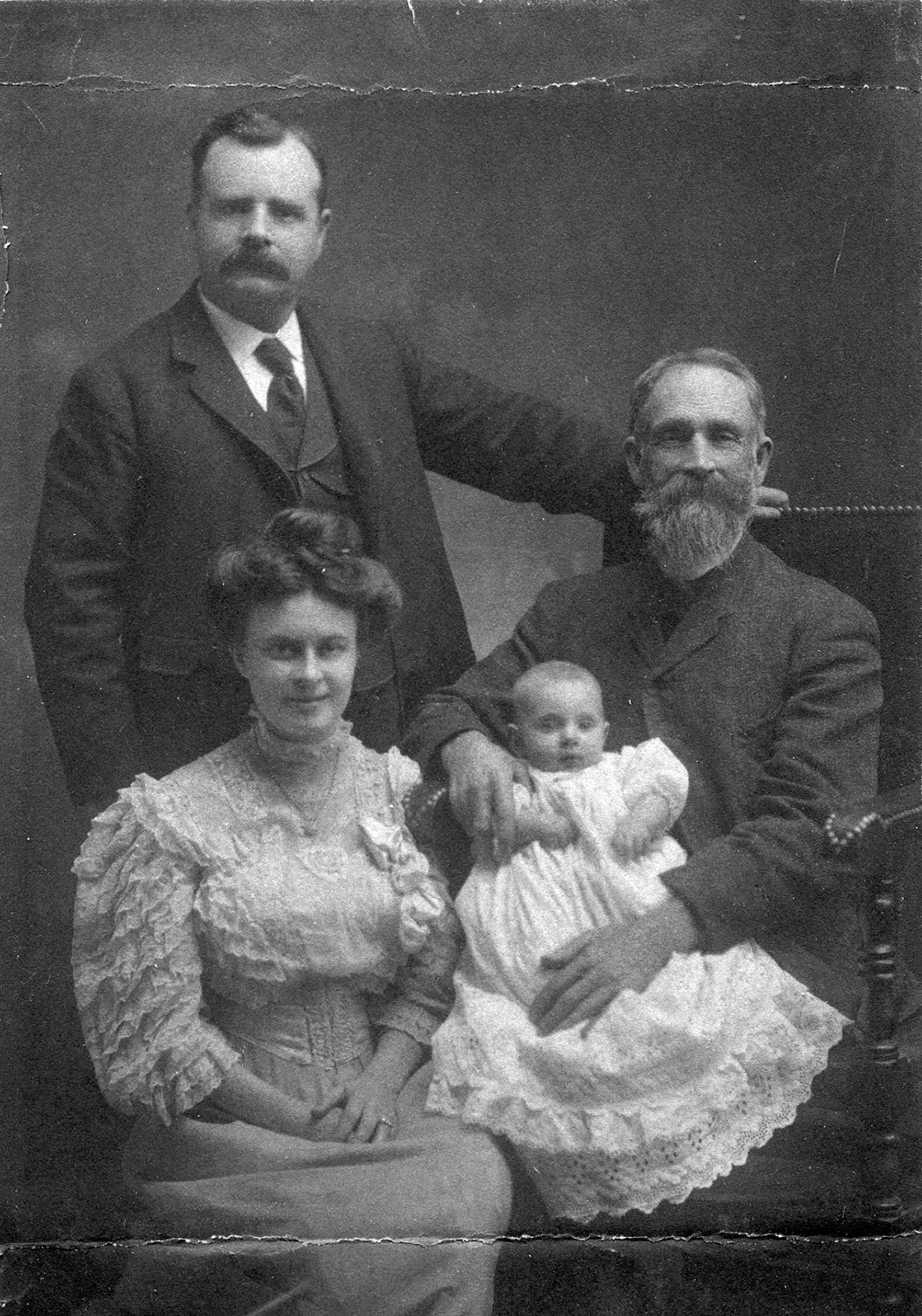

A story of two families

What a story the Macdonell-Williamson House and property can tell! Its location – with a commanding view overlooking the Ottawa River (where goods and people...

- 05 Dec 2014

- Archaeology

Buildings and architecture - Author: Dena Doroszenko and Romas Bubelis,

Perspectives on a site: Artifacts, fragments and layers

When the Trust conserves a property as complex as Macdonell-Williamson House, we consider a variety of perspectives related to the site as an artifact –...

- 05 Dec 2014

- Buildings and architecture

Cultural objects - Author: Sam Wesley,

Understanding Macdonell-Williamson House through four artifacts

It is tempting, while admiring Macdonell-Williamson House’s centuries-old stone walls, Palladian grandeur and picturesque setting, to conjure up an era defined by continuity – when...

- 05 Dec 2014

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Michael Csiki, Majula Koita and Chantel Godin,

Engineering a solution: A structural perspective of Macdonell-Williamson House

The structural rehabilitation of Macdonell-Williamson House has provided a great opportunity for the engineers at Quinn Dressel Associates to contribute to the preservation of a...

- 14 Feb 2014

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity

Adaptive reuse - Author: Janet Gates,

One hundred years of entertainment

Birthdays are about celebration and, in the case of Toronto’s Elgin and Winter Garden theatres, a toast to 100 years of entertainment history. In 2013...

- 06 Sep 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity - Author: Erin Semande,

Partnering for conservation

The Ontario Heritage Trust has a number of conservation tools available to protect and preserve heritage throughout the province. Conservation easements are voluntary legal agreements...

- 06 Sep 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity

Adaptive reuse - Author: Thomas Wicks,

Treading the boards

Performance venues command an important presence in Ontario communities. They tell us about the aspirations of the people who built them, and they reflect the...

- 06 Sep 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity

Adaptive reuse - Author: Pamela Cain,

Second run: A new life for an Ontario theatre

Since the early 1970s, Magnus Theatre in Thunder Bay has made a commitment to urban renewal and the reuse and repurposing of community buildings. The...

- 06 Sep 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity - Author: Wayne Kelly, Romas Bubelis, Brett Randall and Beth Hanna,

Perspectives: The Elgin Theatre at 100

Looking back by Wayne Kelly When theatre entrepreneur Marcus Loew brought Loew’s Theatrical Enterprises to Toronto in 1912, he envisioned an “intricate, moneymaking machine,” a...

- 10 May 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Tools for conservation - Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

Resources: Building communities: Heritage conservation districts

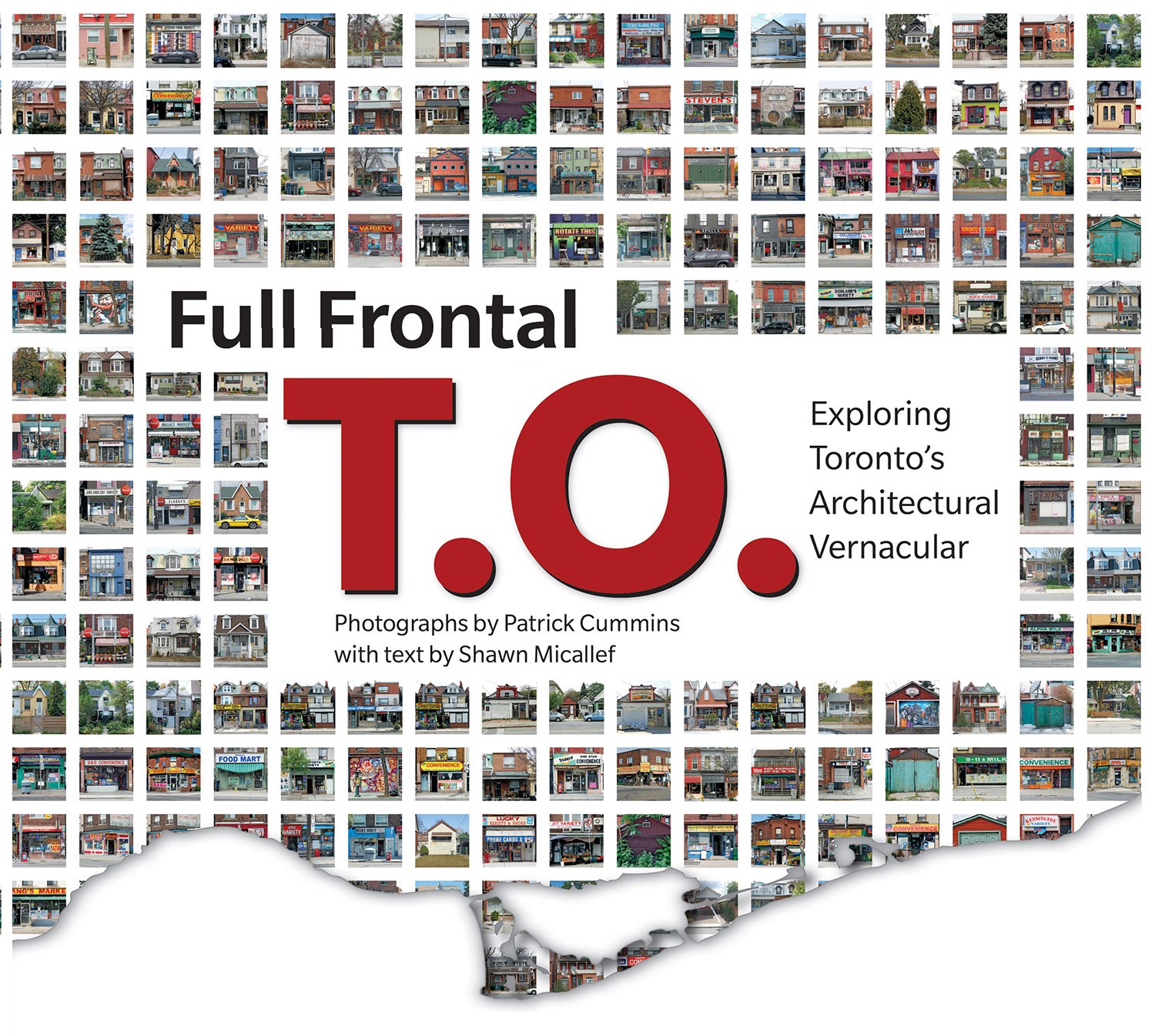

What's on the shelf Full Frontal T.O. – Exploring Toronto’s Architectural Vernacular, by Shawn Micallef with photographs by Patrick Cummins. Coach House Books, 2012. For...

- 10 May 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Tools for conservation - Author: Jim Leonard,

Heritage conservation districts: The most popular tool in the heritage toolkit?

When the Ontario Heritage Act came into force in 1975, municipalities across the province suddenly had the authority to protect and enhance “groups of properties...

- 10 May 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Tools for conservation - Author: Mark Warrack,

How districts change

Meadowvale Village – a once-small, rural village – is located on the Credit River at the north end of the City of Mississauga. In the...

- 10 May 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Tools for conservation - Author: Joan Mason,

Grassroots heritage: The stewards of New Edinburgh

Located in the City of Ottawa at the confluence of the Rideau and Ottawa rivers is the historical community of New Edinburgh. With its roots...

- 10 May 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Stephen Ashton,

Heritage conservation people

Growing up in Port Hope fostered a belief that every community had an amazing main street. That ignorance was shaken when I returned from university...

The Goderich story: A lesson in survival

For the past 18 months, West Street in Goderich has been as much a construction site as it has a place of service and retail...

- 15 Feb 2013

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity - Author: Bruce Beaton,

Off the wall

Storytelling takes inspiration from many sources. Traditionally, museums weave a narrative from real objects: a vase, a coat, a building or a historical site. At...

- 12 Oct 2012

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

Resources: Back to the land

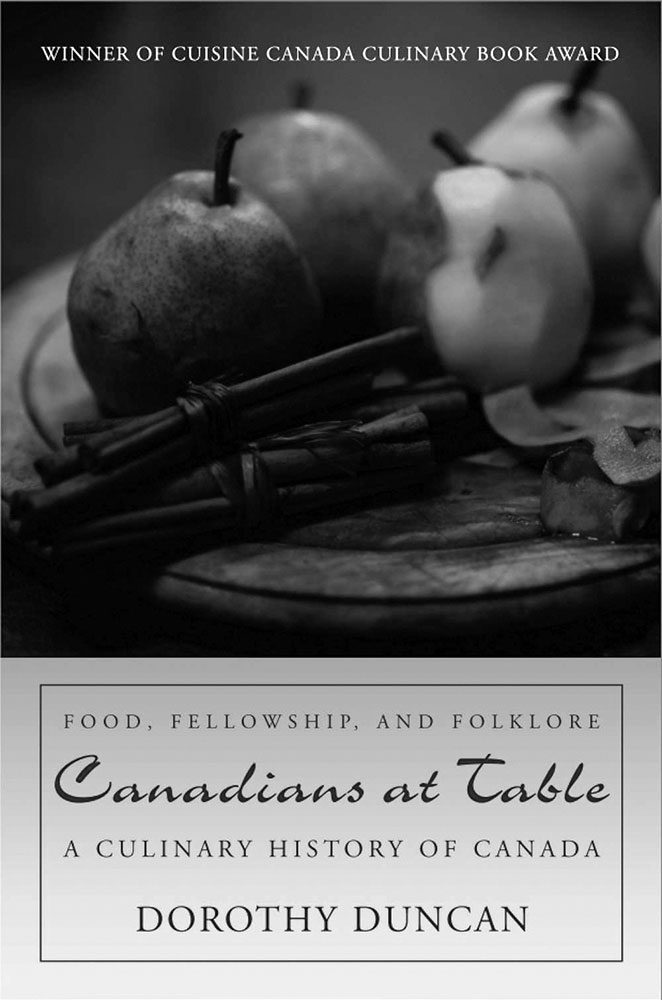

What's on the shelf Canadians at Table: A Culinary History of Canada (by Dorothy Duncan) Dundurn Press, 2011. In Canadians at Table, we learn about...

- 12 Oct 2012

- Cultural landscapes

Food - Author: Wendy Shearer,

The evolution of the agricultural cultural landscape

The agricultural cultural landscape visible today is a comprehensive record of the small- and large-scale changes in the industry that at one time was a...

- 12 Oct 2012

- Community

Cultural landscapes - Author: Catharine A. Wilson,

Coming together

Neighbourliness has always been a part of Ontario’s rich agricultural heritage. Much of what we view in the rural landscape today was once created by...

- 12 Oct 2012

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: David Nattress,

Keeping Ontario’s farm heritage alive

In our ever-expanding world, less arable land is available to grow the food we need to survive. As farms disappear across Ontario, buildings and implements...

- 12 Oct 2012

- Cultural landscapes

Food - Author: Kathryn McLeod,

Protecting Ontario's agricultural landscapes: Challenges and opportunities

Agriculture is an integral part of Ontario’s story. It has shaped and impacted the growth and development of communities since the province began. Although agriculture...

- 12 Oct 2012

- Cultural landscapes

- Author: Jim Miller and Christopher Miller,

Thistle Ha’: A national historic farm

Thistle Ha’, a farm in Pickering, was settled by Scottish immigrant John Miller in 1839. Miller and his family were renowned for their livestock importation...

- 31 May 2011

- Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Thomas Wicks,

Heritage in the public realm: Everything old is new

Ontario is growing. As municipalities across the province expand, so too does the need to revitalize existing municipal facilities to house and adapt to new...

- 31 May 2011

- Buildings and architecture

Natural heritage

Community

Tools for conservation - Author: Sean Fraser, Erin Semande and Mike Sawchuck,

Investing in preservation

It is an unfortunate reality that the preservation of our heritage remains the exception rather than the norm. What is a common-sense approach to living...

- 31 May 2011

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Wayne Kelly,

The roots of democracy: Ontario’s first parliament buildings

As the bicentennial of the War of 1812 approaches, excitement is building at the site of Ontario’s first parliament buildings in Toronto. Responding to fears...

- 28 Jan 2011

- Women's heritage

Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity

Adaptive reuse - Author: Catrina Colme,

Doris McCarthy’s Fool’s Paradise will inspire future generations of artists

With the passing of Doris McCarthy on November 25, 2010, the country lost a revered and talented artist, best known for her landscape paintings. McCarthy’s...

- 28 Jan 2011

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Michael Eamon,

Into the Kawarthas

When visitors first enter Peterborough’s stately city hall, they should look down. Inspired by the City Beautiful Movement – active in Canada from 1893 to...

- 28 Jan 2011

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Barb McIntosh,

Peterborough’s Living History Museum

Hutchison House holds a special place in the social history of Peterborough. Local volunteers built the house in 1836 to persuade one of their first...

- 28 Jan 2011

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Jim Leonard,

Recovering from disaster

On the afternoon of July 14, 2004, the skies opened up over the city of Peterborough. Throughout the day, evening and especially overnight, the city...

- 28 Jan 2011

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Dennis Carter-Edwards,

Exploring the Trent -Severn Waterway

Built over a period of 87 years, the Trent-Severn Waterway stretches 386 kilometres across the heartland of the province, linking Lake Ontario with Georgian Bay...

- 07 Oct 2010

- Community

Cultural landscapes - Author: Beth Anne Mendes,

The People’s park

Queen’s Park, Toronto, was officially opened by the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) in September 1860, and was a forerunner of the late-19thcentury...

- 06 May 2010

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

Resources: Finding our place in Ontario’s history

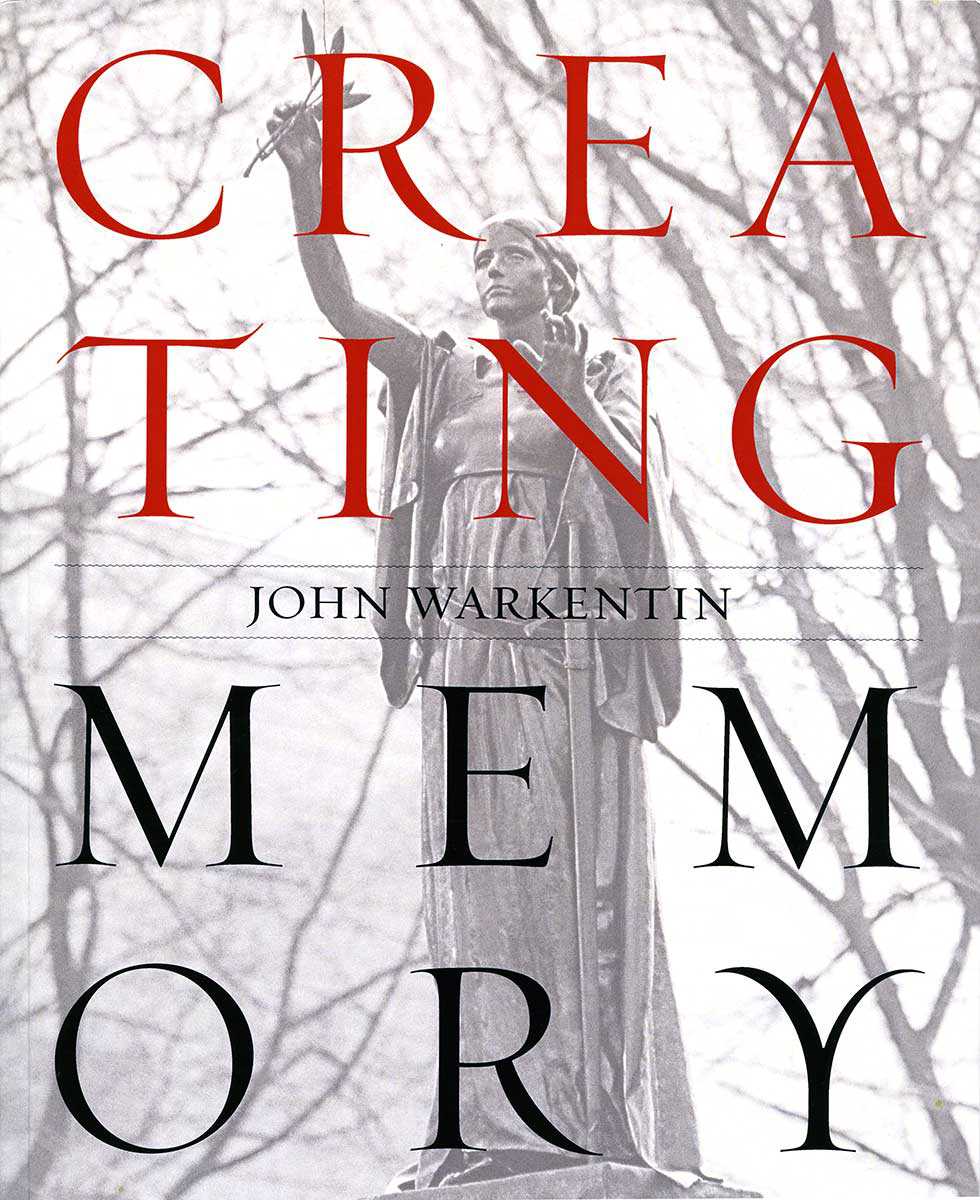

On the shelf Creating Memory, by John Warkentin Becker Associates, 2010. Toronto has over 6,000 public outdoor sculptures, works of art that provide a sense...

- 06 May 2010

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Regan Hutcheson and Leah Wallace,

Designations in bulk

Understanding Unionville, by Regan Hutcheson A visit to Unionville is like a journey back in time. Located north of Toronto in the heart of Markham...

- 06 May 2010

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Sally Coutts,

Leading by example

Ontario towns and cities have been designating properties under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act since the passage of the act in the 1970s...

- 06 May 2010

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Dave Benson,

Cataloguing a community

The amalgamated municipality of Chatham-Kent includes a number of early settlements that encompass thousands of heritage buildings. Recently, Heritage Chatham-Kent (HC-K), our municipal heritage committee...

- 06 May 2010

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Jim Leonard,

What a difference a day makes

On March 11, 2009, Brampton City Council designated 17 individual properties under Part IV (Section 29) of the Ontario Heritage Act. The simultaneous passing of...

- 06 May 2010

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Romas Bubelis,

Tracking Olmsted in Ontario

An undiscovered legacy of work left by landscape architects Charles and Frederick Olmsted Jr. exists in fragments of landscape across Ontario. Their father, Fredrick Law...

- 06 May 2010

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Romas Bubelis,

Maintaining a national treasure

Toronto’s Elgin and Winter Garden Theatre Centre is an inward-looking building of interior architecture. The exterior, by contrast, appears massive but plain. The singular exception...

- 11 Feb 2010

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Evelyn G. McLean,

Walkerville: The heritage of a company town

Among the shrinking number of 19th-century company towns, Walkerville – part of the City of Windsor since 1935 – remains an outstanding example of what...

- 11 Feb 2010

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Kiki Aravopoulos,

Seeing better days

The St. Thomas Canadian Southern Railway station (CASO) occupies a prominent position on the city’s main street. Perhaps it is the station’s sheer size –...

- 11 Feb 2010

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Kathryn McLeod,

Exploring Ontario’s southern peninsula

As you roam the highways and waterways of Ontario’s southern peninsula, a tapestry of stories unravels. These stories speak about settlement and growth, a testament...

- 11 Feb 2010

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Cultural landscapes - Author: Dave Benson,

The history of Chatham-Kent

Chatham-Kent’s rich cultural heritage began long before European settlement when large stockaded villages and Neutral Indians dominated the Thames River and the Lake Erie-Lake St...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Alison Little,

A legacy of support: Faith-based community

Reaching out to those in need has long been a part of Ontario’s religious tradition. Faith-based groups offering medical and social assistance arrived with the...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Jennifer Drinkwater,

Toronto’s synagogues: Keeping collective memories alive

Collective memory is cultural memory – what is remembered about an event by a social or cultural group that experienced it and by those to...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

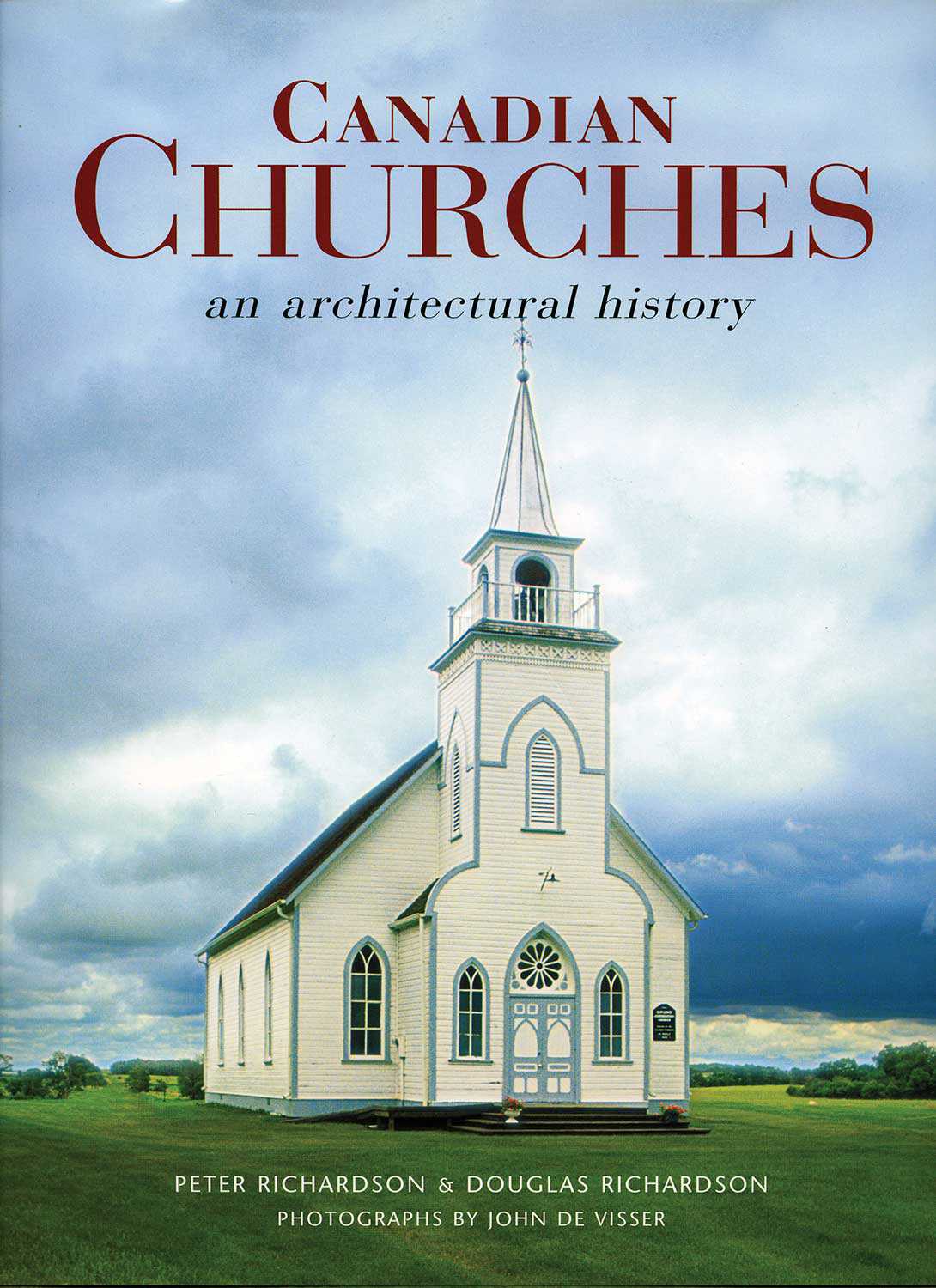

Places of Worship resources

Publications Churches: Explore the symbols, learn the language and discover the history, by Timothy Brittain-Catlin Collins Press. Churches and cathedrals, intentionally imposing and dignified, contain...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Marybeth McTeague,

Ontario’s postwar places of worship: Modernist designs evoke traditional styles

The years following the Second World War were characterized by a sense of renewal and optimism. Places of worship built in Ontario during this period...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Jennifer Laforest,

Adapting today’s places of worship

Adaptive reuse of religious buildings can simultaneously preserve significant heritage sites and benefit communities, but in Ontario those who want to make these conversions face...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Candace Iron and Malcolm Thurlby,

Gothic traditions in Ontario churches

The importance of worship in 19th-century Ontario can be measured by the church buildings erected in the province during that time. Invariably, Ontario denominations turned...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: David Cuming,

From Hamilton, a municipal perspective

Places of worship are often stunning buildings, constructed in forms and styles that have existed for thousands of years around the world, using specialized techniques...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity - Author: Nicholas Holman,

The music of worship

Goethe said that “architecture is frozen music,” but why did he say this? Was it because Christian church interiors, with their columns and arches, seem...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity - Author: Erin Semande,

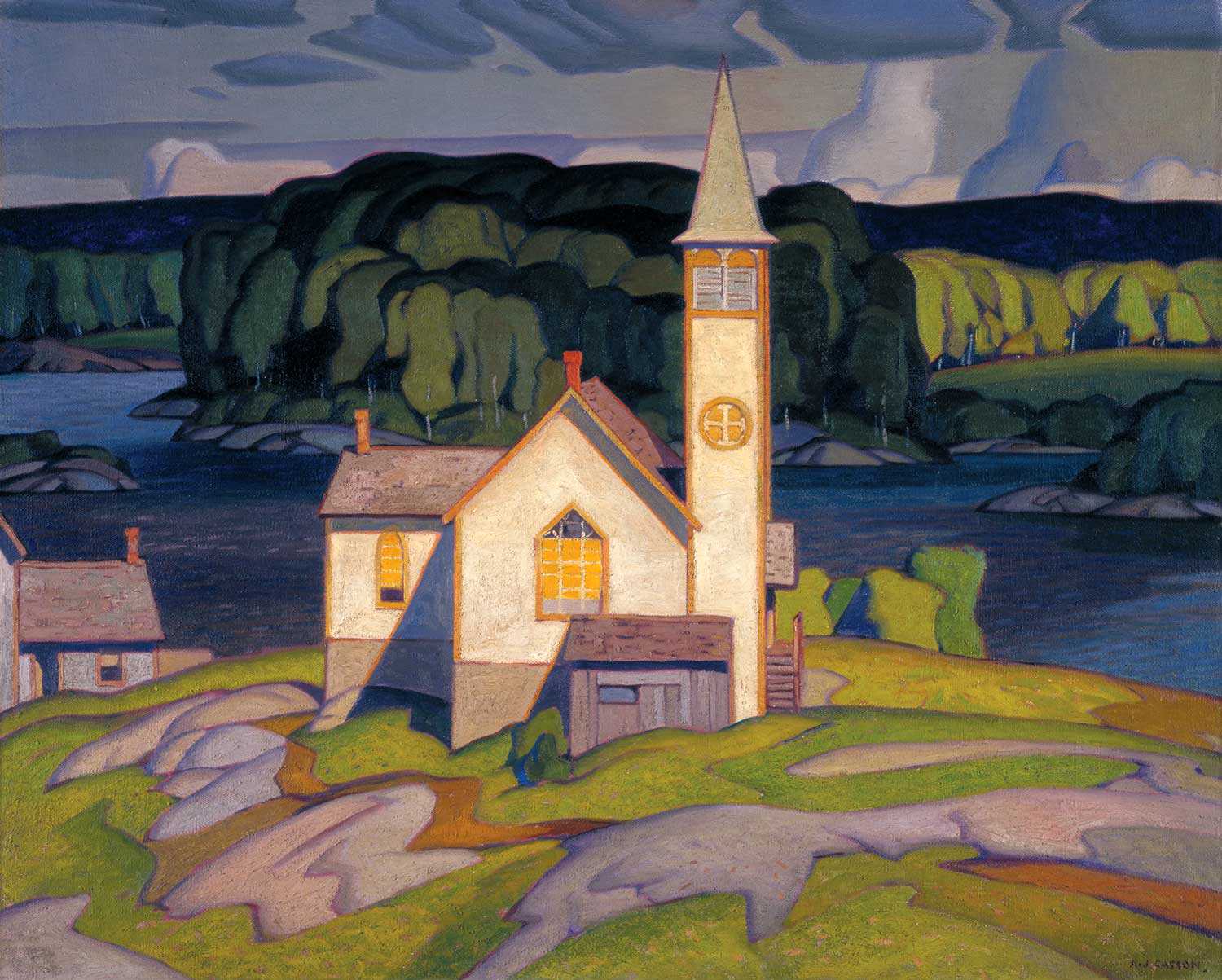

Art in the church and the church in art: Work of the Group of Seven

Talented and renowned artists have long been commissioned to decorate the interiors of places of worship, where they often turn the walls and ceilings into...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Vicki Bennett,

Form and function: The impact of liturgy, symbolism and use on design

During the 19th century, the location, physical condition and stylistic merit of churches were publicly discussed as reliable indicators of a community’s value, moral fabric...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Jane Burgess and Ann Link,

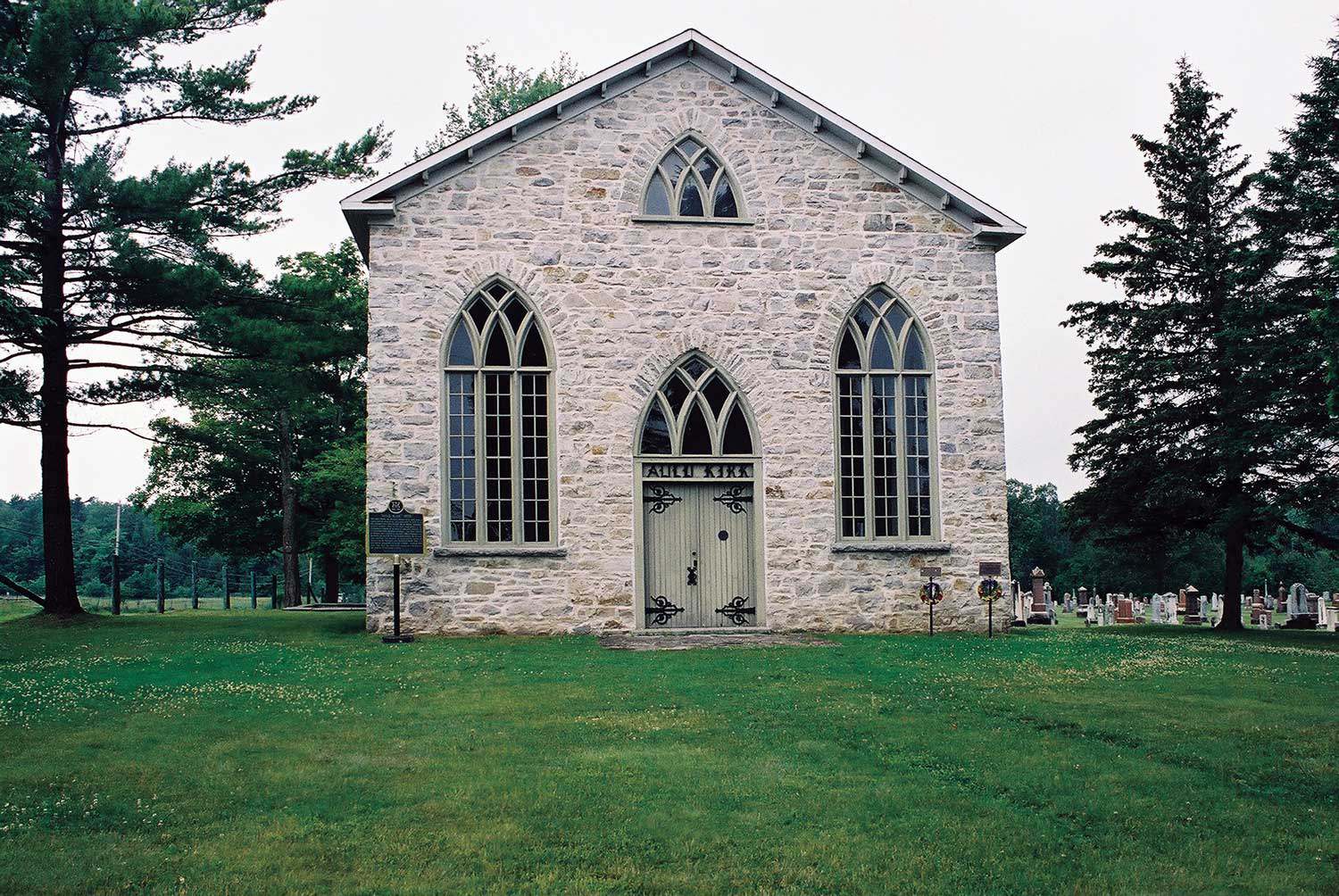

Enduring stewardship preserves a treasured heritage church

Located just east of Beaverton, the Old Stone Church, built in 1840 by a predominantly Scottish congregation, is a simple but handsomely proportioned small Georgian...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Laura Hatcher,

The changing face of worship

The architectural style, massing, materials and date stones of a place of worship offer clues about the congregation’s history and values. Likewise, the building’s size...

Religious freedom in the promised land

Eli Johnson toiled on plantations in Virginia, Mississippi and Kentucky before making his bid for freedom in the “promised land” – the term used by...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Cultural landscapes - Author: Wendy Shearer,

Places of worship in Ontario’s rural cultural landscape

The cultural landscapes of rural southern Ontario contain a variety of heritage resources – land patterns and uses, built forms and natural features. Within these...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Indigenous heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Yves Frenette,

Churches of “New Ontario”

In the middle of the 19th century, northern Ontario remained much as it had been under the French regime – a region of Catholic missions...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Indigenous heritage

Buildings and architecture

Francophone heritage

Community - Author: Wayne Kelly,

Ontario’s rich religious heritage

From the First People who for thousands of years conducted religious and cultural ceremonies at places they believed held spiritual significance, to subsequent arrivals who...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Indigenous heritage

Buildings and architecture

Community

Cultural objects - Author: Kathryn McLeod,

Christ Church and the Queen Anne Silver

Located in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory on the Bay of Quinte, Christ Church houses a silver communion service dating to 1712. This remarkable service represents an...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Richard Moorhouse,

Launching the Places of Worship Inventory

Survey, documentation and research – these are the first steps in the conservation process. How can decisions be made about our heritage without first acquiring...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity

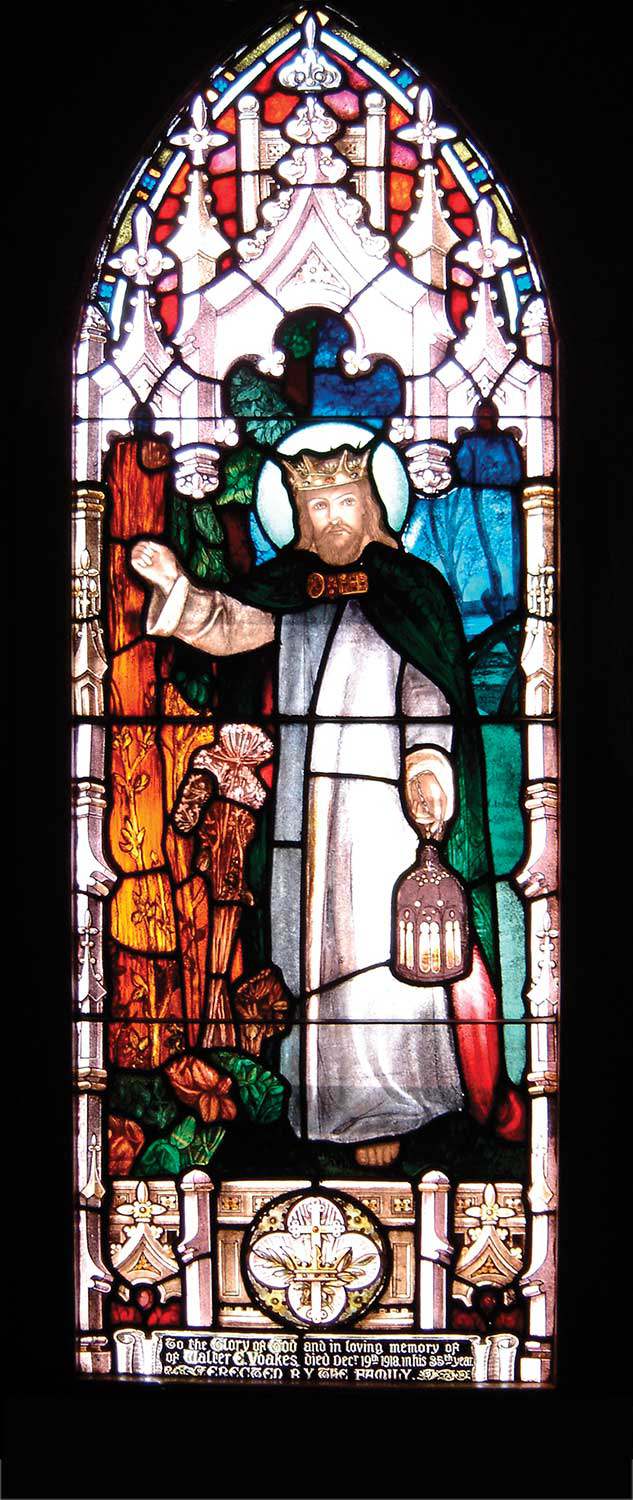

Cultural objects - Author: John Wilcox,

Adventures in light and colour

Light is a fundamental aspect of all architecture, especially places of worship. Light has always been considered a manifestation of the spirit, providing guidance, comfort...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Bruce Pappin,

The challenge of change in the Catholic Diocese of Pembroke

In May 2006, the Catholic parish of Ste Bernadette in the small northern Ontario community of Bonfield celebrated the 100th anniversary of its church. A...

- 10 Sep 2009

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Sean Fraser,

The challenges of ownership

Historic places of worship may possess cultural heritage values that engender public support for their preservation, but these values sometimes differ from the spiritual and...

- 28 May 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Tools for conservation - Author: Sean Fraser,

Subsidizing demolition

In nature, there is no such thing as waste. Nature operates in an endless web of interconnected cycles of use, transformation and reuse. The concept...

- 28 May 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Natural heritage

Community - Author: Tamara Chipperfield and Kiki Aravopoulos,

Heritage in harmony: The integration of natural and cultural landscapes

Approximately 11,000 years of human culture are recorded in Ontario’s landscapes. Most existing natural landscapes in Ontario today have intrinsic cultural heritage meaning and significance...

- 28 May 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Erin Semande,

The sustainability of place

Located on the Lake Huron shore at the mouth of the Maitland River, Goderich is known as “Canada’s Prettiest Town.” It is situated in what...

- 28 May 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Joe Lobko and Megan Torza,

Rebirth of the Wychwood Barns

The Artscape Wychwood Barns – near St. Clair Avenue West and Bathurst Street in Toronto – were created when five historic streetcar maintenance barns were...

- 28 May 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Environment - Author: L.A. (Sandy) Smallwood,

Discarding the past

When an old building is torn down, we lose more than just the structure. We lose a bit of our past. The foundation walls and...

- 12 Feb 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Kathryn McLeod,

Heritage off the 401

Highway 401, stretching from Windsor to the Quebec border, is one of the busiest highways in North America. Anyone who has journeyed east of Toronto...

- 12 Feb 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Romas Bubelis,

Building on the past

Eastern Ontario offers an array of impressive historic houses. Some of these houses – owned and operated by the Ontario Heritage Trust – are featured...

- 12 Feb 2009

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Michael Vidoni,

La nouvelle St. Brigid

L’église catholique St. Brigid d’Ottawa est entrée dans une nouvelle ère. Depuis presque 120 ans, elle se dresse au cœur d’un quartier divers et dynamique...

- 12 Feb 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Glenda Jones,

From mill to museum

The big oak door of the Mississippi Valley Textile Museum in Almonte in eastern Ontario swings silently open as it has done for over 10...

- 12 Feb 2009

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Wayne Kelly and Kathryn McLeod,

Ontario's eastern treasures

Inhabited by Aboriginal Peoples for 7,000 years, present-day eastern Ontario is rich with heritage. The area gradually transformed as French and later United Empire Loyalists...

- 12 Feb 2009

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Ellen Kowalchuk,

The Rockwood story

Behind the stately façade of Kingston’s Rockwood Villa lies the history of mental health services in Ontario. Built in 1842 as a residence for local...

- 11 Sep 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Romas Bubelis,

The character of adaptive reuse

In his 1947 essay titled “The Past in the Future,” architectural historian John Summerson (1904-92) offered this description of an old building. He was speaking...

- 11 Sep 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Erik R. Hanson,

Second chances for Peterborough’s priceless heritage

One of the greatest challenges to creating a healthy downtown is getting people to live there. While Peterborough’s historic centre is full of beautiful heritage...

- 11 Sep 2008

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Sean Fraser,

The heritage of faith – Ontario’s places of worship

In 2006, the Ontario Heritage Trust began compiling an inventory of significant pre-1982 purpose-built places of worship located throughout the province. These remarkable cultural treasures...

- 11 Sep 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Marcus R. Létourneau,

Kingston’s heritage: Time and again

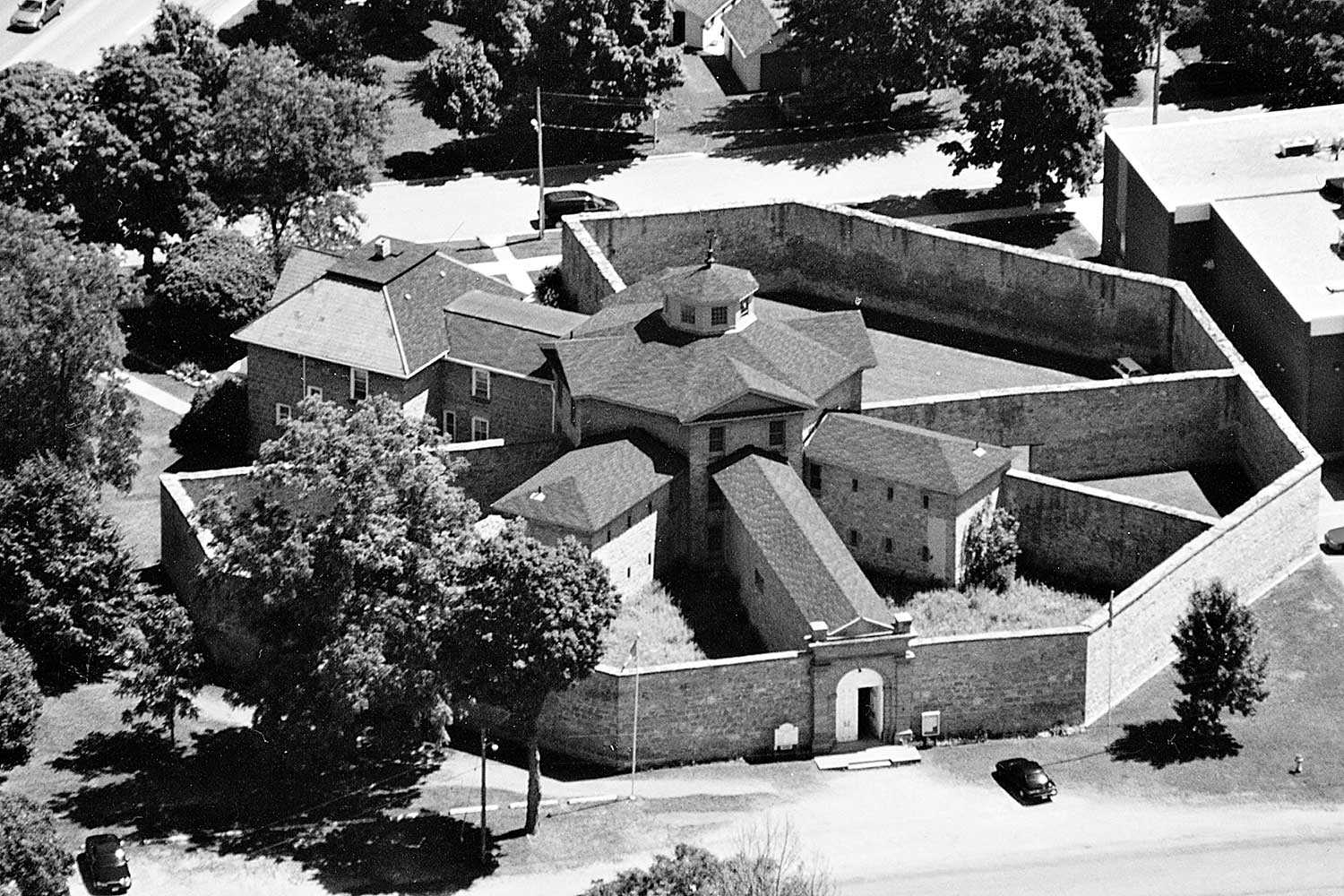

The City of Kingston sits at a strategic location, halfway between Montreal and Toronto, where Lake Ontario meets the western end of the St. Lawrence...

- 11 Sep 2008

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Beth Anne Mendes and Erin Semande,

Alma College remembered

By mid-afternoon on Wednesday, May 28, 2008, Alma College in St. Thomas was reduced to a smouldering ruin. The loss of this significant site to...

- 11 Sep 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Sean Fraser,

Understanding adaptive reuse

In our efforts to conserve heritage properties, finding a use can be our greatest challenge and our greatest opportunity. An unused, vacant heritage building is...

- 12 Jun 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Thomas Wicks,

A renaissance of northern heritage

After railway development connected this once-isolated area to the rest of the province at the end of the 19th century, the abundant natural resources attracted...

- 12 Jun 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Denis Héroux,

Adventurous workers wanted for remote locations – Housing provided

The exploration, settlement and development of northern Ontario were motivated by the exploitation of the region’s natural resources – primarily fur, timber, gold and silver...

- 12 Jun 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Romas Bubelis,

Northern icons

The towering McIntyre Mine Headframe in Timmins. The Clergue Block House and Powder Magazine in Sault Ste Marie. St. Francis of Assisi Anglican Church in...

- 12 Jun 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Cultural landscapes - Author: Sean Fraser,

The historical Cobalt Mining District – A community resource

At the turn of the 20th century, Cobalt was a small and isolated lumber camp. In August 1903, two lumbermen – James McKinley and Ernest...

- 14 Feb 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Cultural objects - Author: Kathryn Dixon,

Friends of the Trust

Throughout its 40 years, the Ontario Heritage Trust has developed strong partnerships with local communities. Among these partnerships are those with the groups whose efforts...

- 14 Feb 2008

- Buildings and architecture

Arts and creativity

Adaptive reuse - Author: Gordon Pim,

Raising the curtain: How the Winter Garden Theatre was rediscovered

In December 1913, Loew’s Yonge Street Theatre – the Canadian flagship of the mighty Loew’s empire – opened in Toronto. Two months later, the opulent...

- 14 Feb 2008

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Sean Fraser,

The past empowered

The buildings, structures and landscapes that comprise our cultural heritage are products of the intricate interplay between people and place over time. What is preserved...

- 14 Feb 2008

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Sean Fraser,

Have you seen this building?

In November 2007, the Sir Aemilius Irving House in Hamilton was demolished by its owner to make way for a new building. Unfortunately, local heritage...

- 14 Feb 2008

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Beth Hanna,

Enoch Turner Schoolhouse – a citizen’s legacy

When the province of Ontario introduced the 1847 Common Schools Act, municipalities were given the power to introduce taxes to fund public education. Toronto city...

- 14 Feb 2008

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Laura Hatcher,

Counting our blessings

Built in Glengarry in 1821, St. Raphael’s Church was one of Ontario’s earliest Roman Catholic churches. Constructed under the supervision of Alexander Macdonell – Upper...

- 15 Nov 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Environment - Author: Romas Bubelis,

Building assets

Which is more sustainable – an artificial or live Christmas tree? This is an environmentalist’s conundrum, and it illustrates the paradox of “sustainable” building materials...

- 15 Nov 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Environment

Adaptive reuse - Author: Sean Fraser,

The guiding principles of sustainable architecture

In the late 1990s, the Ontario Ministry of Culture introduced Eight Guiding Principles in the Conservation of Built Heritage Properties, which are in common use...

- 15 Nov 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Environment - Author: Sean Fraser and Karen Abel,

Inside Sheppard’s Bush

Charles Sheppard (1876-1967) moved to the Town of Aurora in 1921, after making his fortune in the Simcoe County lumber industry. Brooklands, his modest estate...

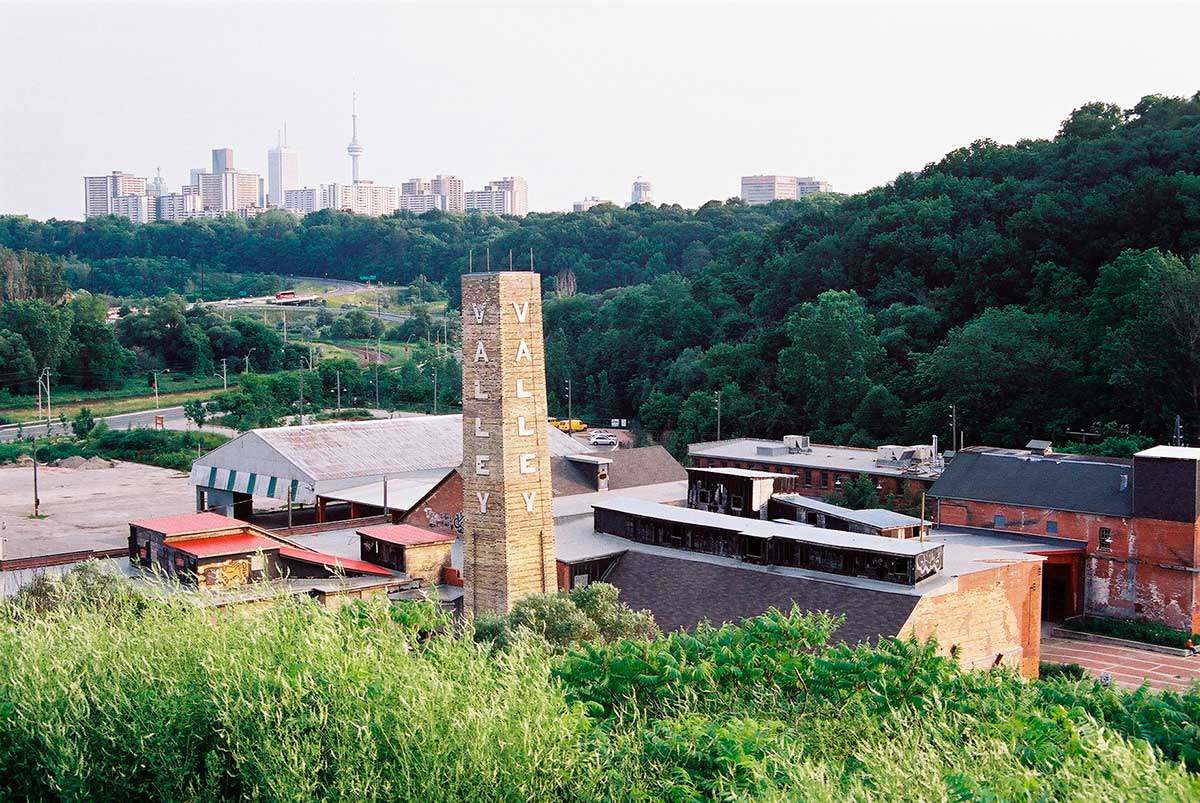

Evergreen Brick Works: Rethinking space

Evergreen – a national charity – builds the relationship between nature, culture and community in urban spaces. With its revitalization of Toronto’s Don Valley Brick...

- 15 Nov 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Beth Anne Mendes,

Discovering the City Beautiful

On July 25, 2007, the Ontario Heritage Trust and the Town of Kapuskasing unveiled a provincial plaque to commemorate the town plan that helped shape...

- 15 Nov 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Environment - Author: Sean Fraser,

Fact or fiction: Demystifying the myths around going green – Moving toward a more sustainable architecture

Sustainable: able to be maintained at a certain rate or level . . . conserving an ecological balance by avoiding a depletion of natural resources...

- 15 Nov 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Environment

Adaptive reuse - Author: Alex Speigel,

Sustainability for old buildings: A developer’s perspective

Adaptive reuse provides a sound and sustainable approach to the renewal of our urban fabric, as illustrated by the conversion of three Toronto buildings to...

- 15 Nov 2007

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Romas Bubelis,

In praise of older windows

Façade: a word of double-edged meaning. Architecturally, it refers to the face of a building. In literature, more often than not, it connotes a front...

- 10 May 2007

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Sean Fraser,

Building on our successes

The Ontario Heritage Trust’s heritage conservation easements conserve some of Ontario’s most significant heritage sites. Good stewardship of easement properties includes regular maintenance and periodic...

- 10 May 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Adaptive reuse - Author: Kathryn Dixon,

The story of Barnum House

Barnum House, on the north side of Highway 2 (Danforth Road), west of Grafton is historically significant for its association with the Barnum family. It...

- 10 May 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Tools for conservation - Author: Beth Hanna,

The R’s of conservation

An earlier generation spoke of the three R’s as “Reading, ‘riting and ‘rithmetic.” They were the fundamentals of education in the 19th century and considered...

- 10 May 2007

- Military heritage

Buildings and architecture - Author: Susan Ramsay and Marnie Maslin,

Battlefield House Museum and Park – A pioneer in the history of preservation

Nestled under the Niagara Escarpment and situated in a park connected to the Bruce Trail, Battlefield House Museum National Historic Site in Stoney Creek is...

- 10 May 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Tools for conservation - Author: Sean Fraser,

Leading the way in municipal heritage planning

What’s happening in your community? With significant amendments to the Ontario Heritage Act in April 2005 and a strengthening of the Provincial Policy Statement (PPS)...

- 15 Feb 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Kiki Aravopoulos,

Exploring Country Heritage Park

In March 2006, the Ontario Heritage Trust acquired a cultural conservation easement on Country Heritage Park. Located in Milton, this designed heritage attraction was created...

- 15 Feb 2007

- Buildings and architecture

Cultural objects

Tools for conservation - Author: Romas Bubelis and Nick Holman,

Heritage conservation at our front door

The term “porte-cochère” has continental flair, though humble origins. In French, it means “carriage door” and originally referred to a covered entryway into a courtyard...

- 15 Feb 2007

- Black heritage

Buildings and architecture

Natural heritage - Author: Gordon Pim,

Heritage by numbers

Ontario’s heritage is an immense and complex jigsaw puzzle. Every individual element of heritage creates a whole . . . a sort of heritage by...

- 07 Sep 2006

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Louise Burchell,

Saving the Spencerville Mill – Preserving community heritage

The Spencerville Mill, a fine cut-stone flour and grist mill, is located on the bank of the South Nation River in the small rural village...

- 07 Sep 2006

- Community

Cultural landscapes - Author: Romas Bubelis,

Rush and remembrance

On a windswept summer day in 2005, a small congregation gathered beside a cloverleaf off-ramp at the western fringe of Toronto. In Richview-Willow Grove Cemetery...

- 07 Sep 2006

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Cultural objects - Author: Erin Semande,

The biography of a house: If these walls could speak

Researching family history is a popular pastime for many who want to uncover their family’s unique past and discover how they contributed to Ontario’s growth...

- 16 Feb 2006

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Tools for conservation - Author: Gordon Pim,

Winning the battle

There are countless examples across the province of successful restorations of Ontario’s treasured heritage sites. Although the challenges are great – funding being the primary...

- 16 Feb 2006

- Buildings and architecture

Community

Adaptive reuse - Author: Sean Fraser,

Our cultural heritage places: how heritage buildings adapt

Although heritage remains a year-round activity for many of us, Heritage Day is celebrated annually on the third Monday in February. This year’s theme speaks...

- 16 Feb 2006

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Gordon Pim,

Snapshots of the past

A flash of phosphorus. A whiff of smoke. And an image is captured. Photographs have chronicled our lives for over 150 years, remaining one of...

- 16 Feb 2006

- Archaeology

Buildings and architecture

Cultural objects

Tools for conservation - Author: Romas Bubelis,

Historic wallpaper: Finding what’s beneath

Wallpapers first appeared in Canada as early as the mid-17th century. These oldest papers were block-printed, hand-painted or stenciled. Pattern and colour was applied to...

- 16 Feb 2006

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: Tim Mallon,

Small-town museums key to small-town success

For 18 years, my wife and I raised our two sons in the Town of Richmond Hill just north of Toronto. When we moved to...

- 16 Feb 2006

- Archaeology

Buildings and architecture - Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

Breaking news: Saving our First Parliament

It was announced on December 21, 2005 that the site of Ontario’s first parliament buildings in Toronto has been saved. The Ontario Government, in partnership...

- 08 Sep 2005

- Archaeology

Buildings and architecture - Author: Dena Doroszenko,

Unearthing the past: Discoveries at Macdonell-Williamson House

Built in 1817, Macdonell-Williamson House in eastern Ontario reflects the ambitions and aspirations of retired fur trader, John Macdonell. His life was fraught with financial...

- 08 Sep 2005

- Buildings and architecture

Community - Author: David Cuming,

Moving forward with heritage conservation

Thirty years ago, when the Ontario Heritage Act was new, I was a young planner with about a year’s experience working in London, England and...

- 08 Sep 2005

- Buildings and architecture

Tools for conservation - Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

The healthy roof: Staying on top of heritage preservation

The following excerpt appears in Well-Preserved: The Ontario Heritage Foundationʼs Manual of Principles and Practice for Architectural Conservation (Third Revised Edition), by Mark Fram (Boston...

- 08 Sep 2005

- Buildings and architecture

Tools for conservation - Author: Barbara Heidenreich and Jeremy Collins,

New natural heritage easement properties

John Edward (Ted) Greenwood Sanctuary On March 30, 2005, the Ontario Heritage Foundation received – from Mary Greenwood of Nakara, Australia – a 100-acre (40-...

- 08 Sep 2005

- Buildings and architecture

Natural heritage

Community

Cultural landscapes - Author: Richard Moorhouse and Beth Hanna,

The new Ontario Heritage Act: The evolution of heritage conservation

An important shift has occurred in Ontario’s legislative framework for heritage conservation. On April 28, 2005, the Ontario Heritage Amendment Act (Bill 60) received royal...

- 19 May 2005

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Larry Wayne Richards,

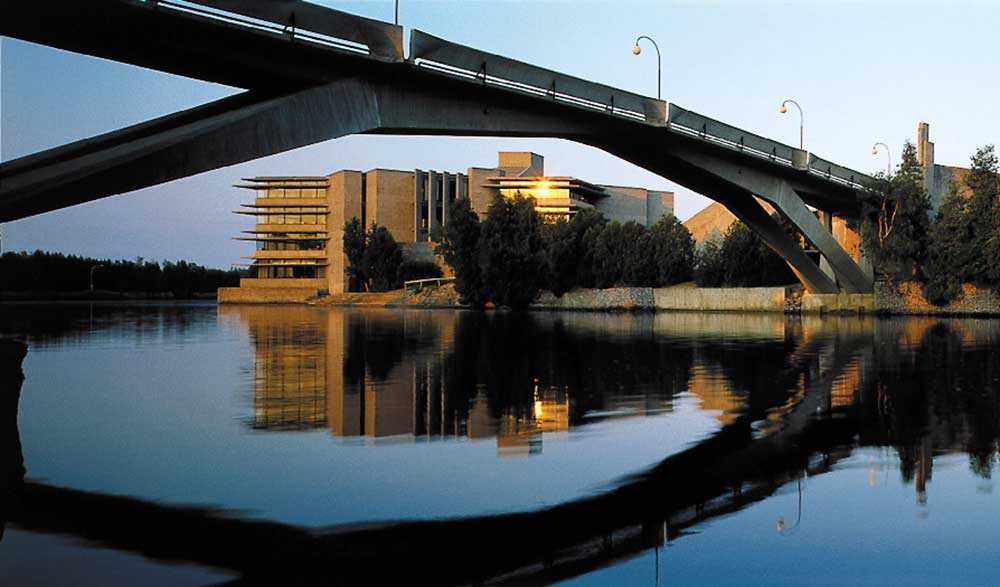

Trent University under the modernist microscope

Throughout the developed world, attention is being given to the built heritage of the modern era. Organizations such as UNESCO's World Heritage Center, the International...

- 19 May 2005

- Buildings and architecture

Tools for conservation - Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

Working with superstructures: The framework for Ontario's heritage buildings

Last issue, we discussed the importance of a solid foundation when preserving heritage structures. In this issue, we see how a buildingʼs skeleton holds everything...

- 19 May 2005

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

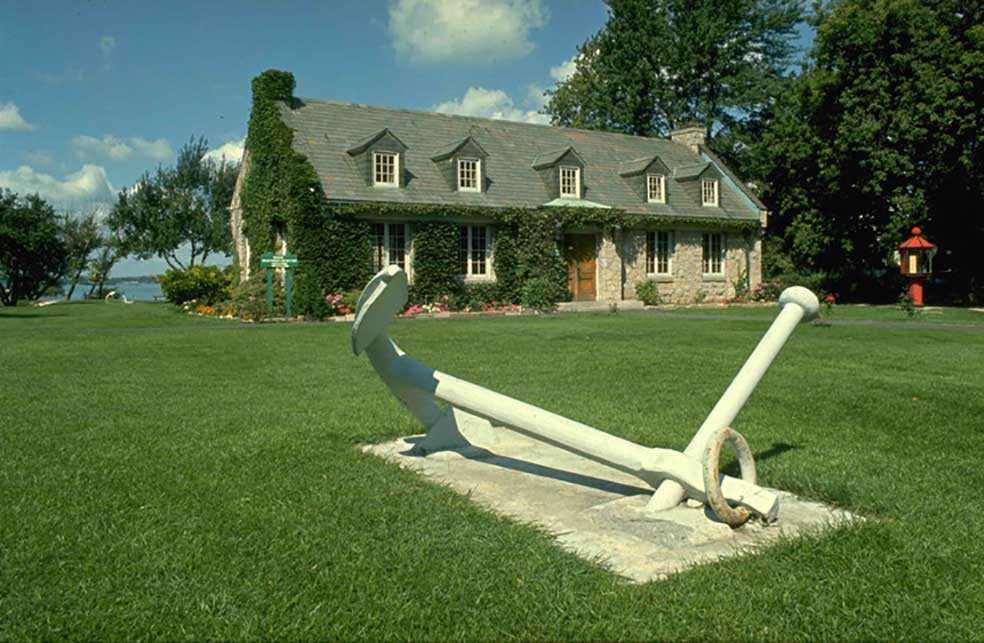

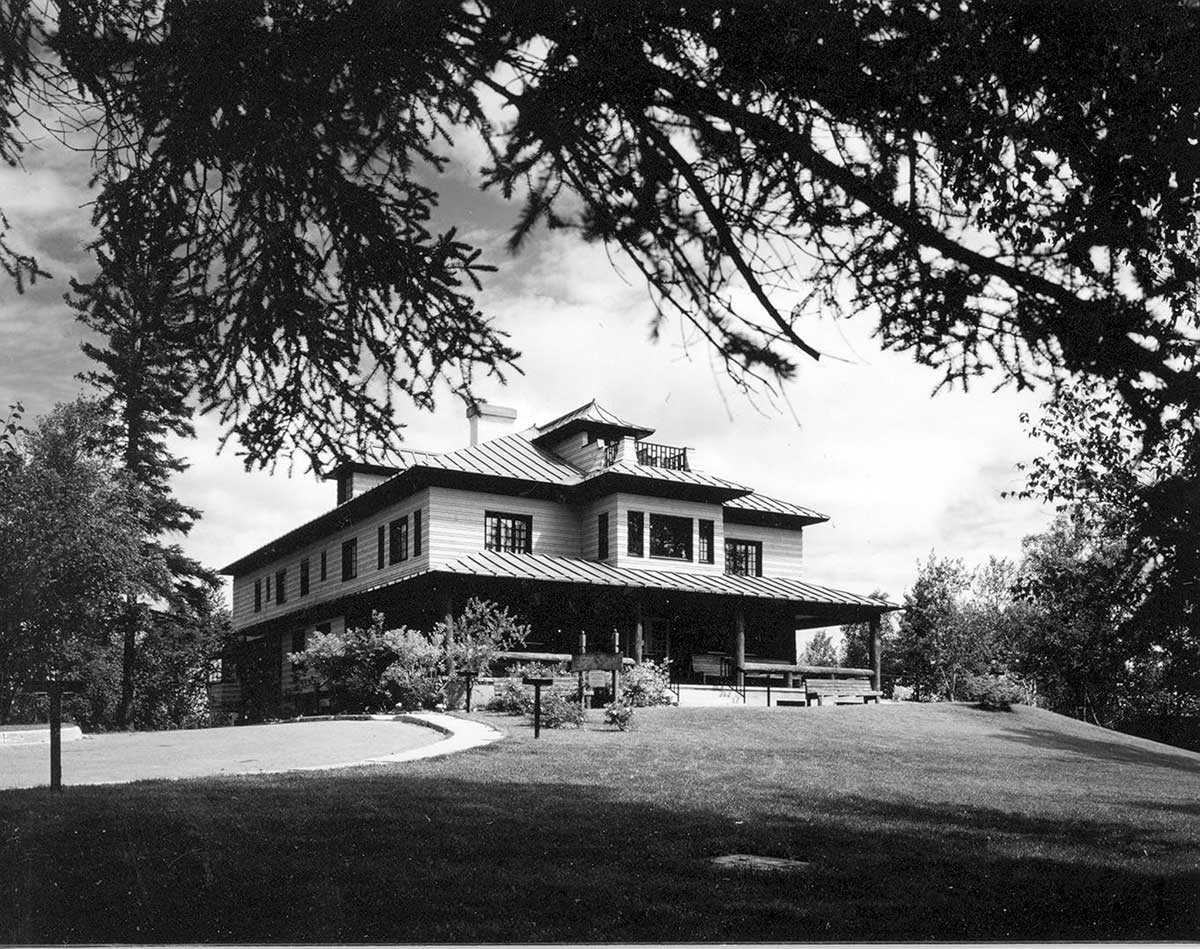

Leidra Lodge – A new conservation easement

June Ardiel has been a patron and leader in Ontario's arts community all her life. She has authored a book on the public art of...

- 19 May 2005

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Moiz Behar,

The changing face of heritage: The International Style – Toronto’s Toronto-Dominion Centre

In the second quarter of the 20th century following the First World War, Europe saw the emergence of a significant movement in architecture. This “modern”...

- 19 May 2005

- Buildings and architecture

Cultural objects - Author: Ontario Heritage Trust,

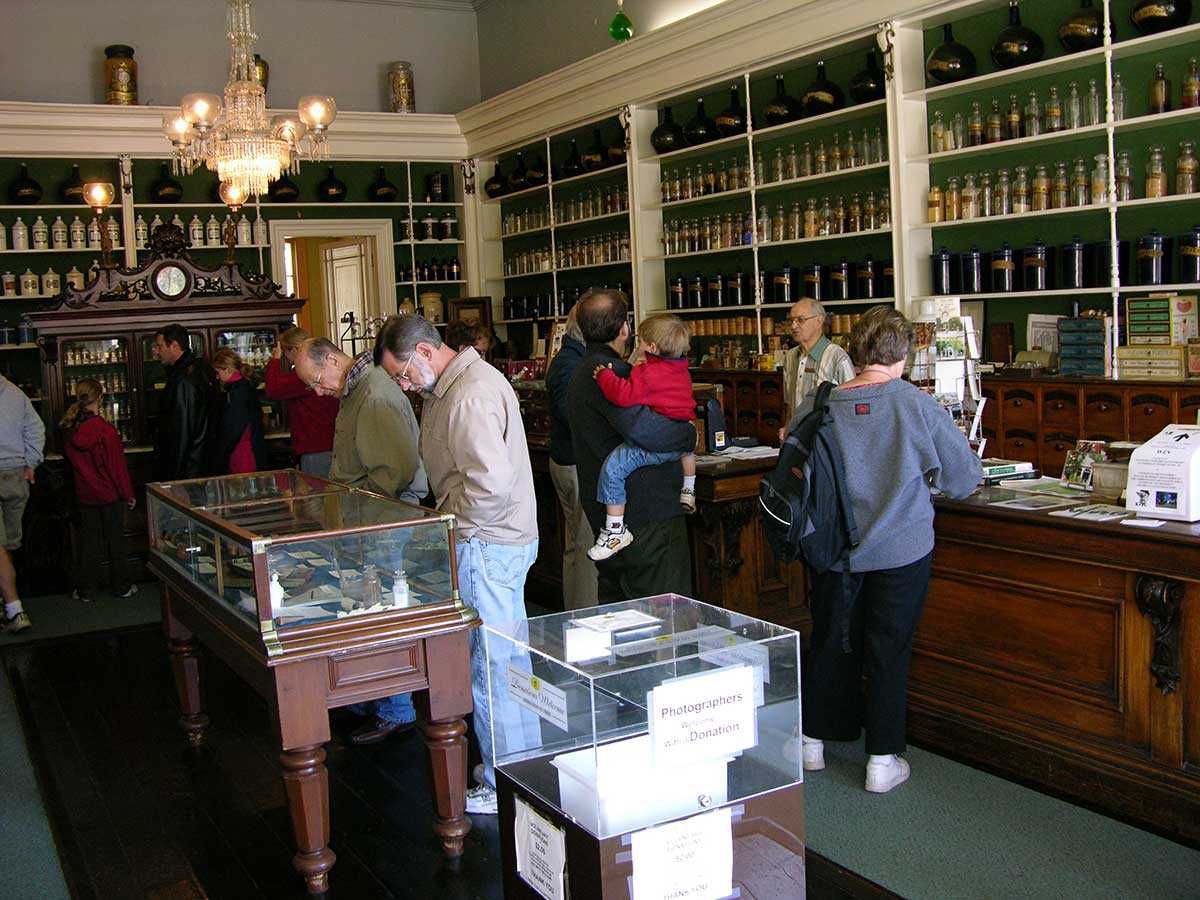

The Homewood collection

As you drive east along Highway 2 between Brockville and Prescott, you will find the robust Georgian Homewood Museum deeply set back from the road...

- 12 Feb 2005

- Black heritage

Buildings and architecture - Author: Wayne Kelly,

Inside Uncle Tom's Cabin

At a bend in the Sydenham River near the town of Dresden stands Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site. The museum – built on the site...

- 12 Feb 2005

- Buildings and architecture

- Author: Sean Fraser,

The Sharon Temple and the heritage of faith

While most of Canada celebrates Heritage Day on the third Monday in February, Ontario celebrates Heritage Week. The theme developed for Ontario Heritage Week 200...

- Accessibility

- Privacy statement

- Terms of use

- © King's Printer for Ontario, 2023

- Photos © Ontario Heritage Trust, unless otherwise indicated.

- Accessibility

- Privacy statement

- Terms of use

- © King's Printer for Ontario, 2023

- Photos © Ontario Heritage Trust, unless otherwise indicated.