Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Adaptive reuse: Building on an architect’s perspective

Ontario Heritage Trust architect, Leroy Shum, on the key elements of adaptive reuse, emerging industry trends and the possibilities of what it all means.

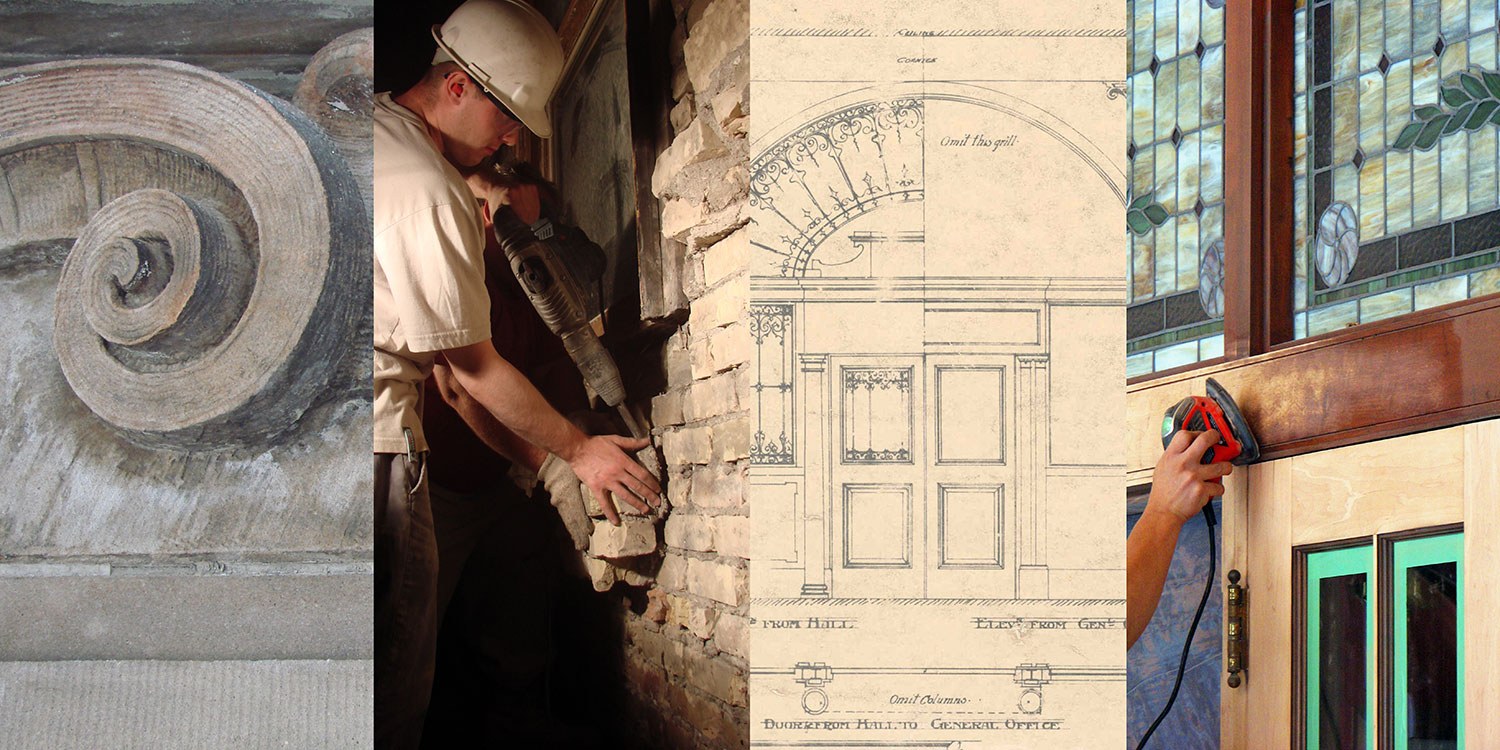

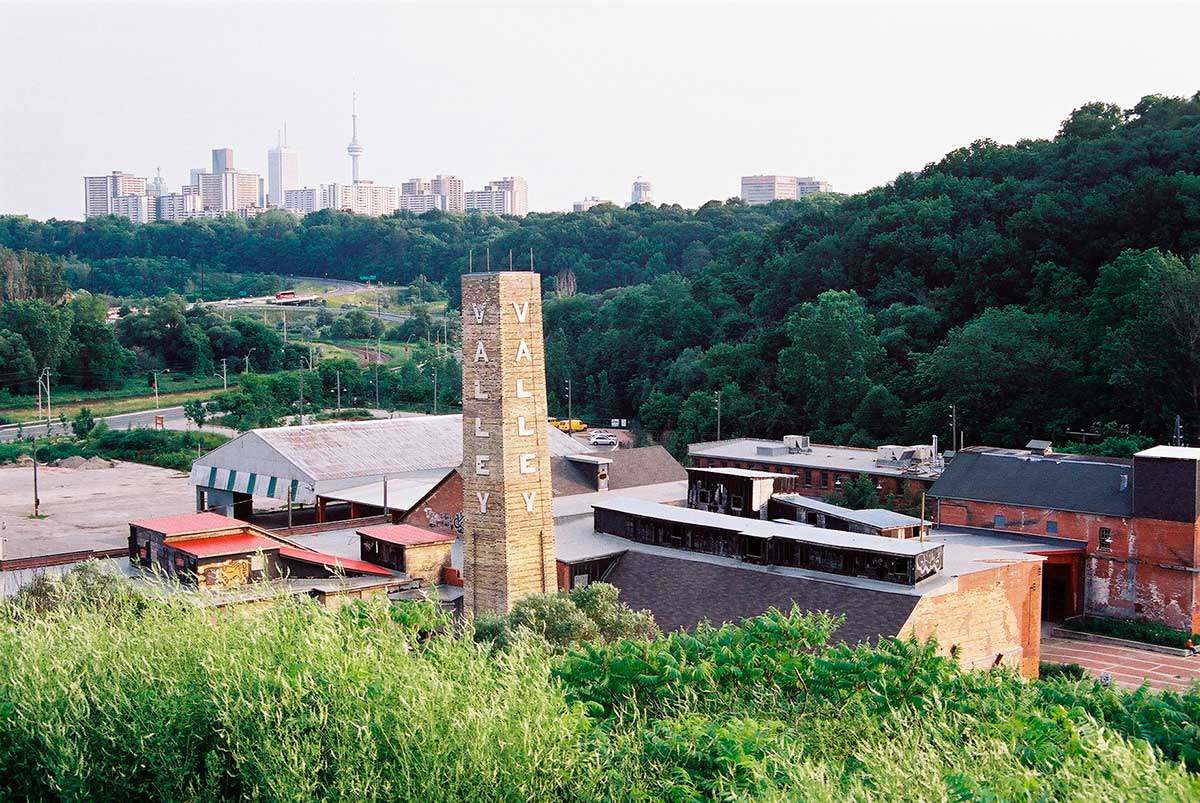

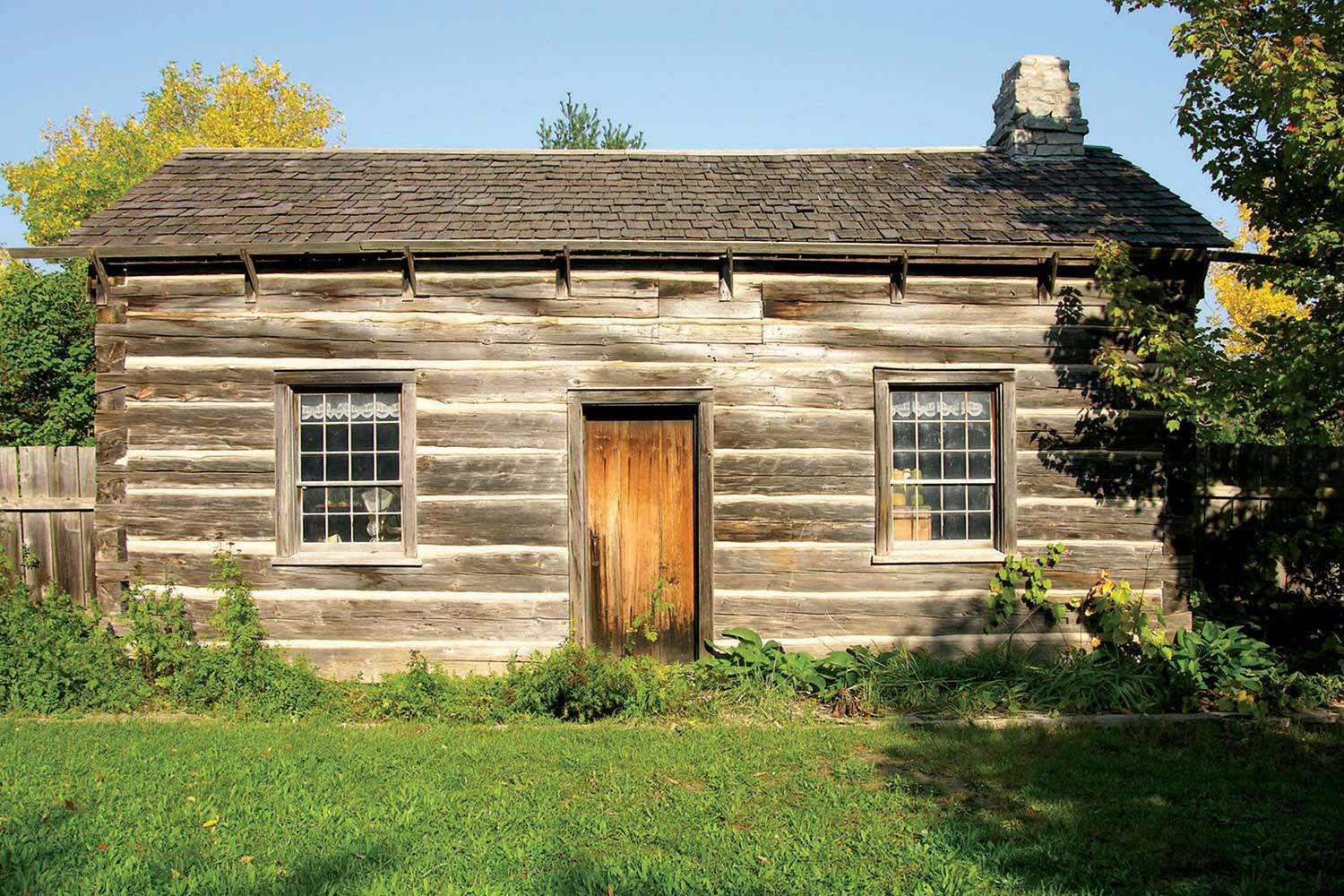

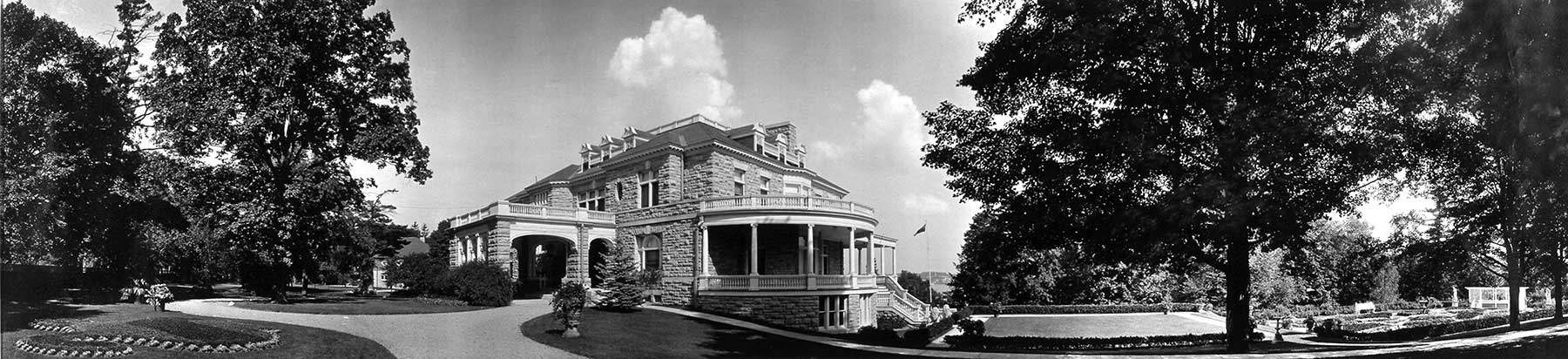

What happens when a building no longer fulfils its intended purpose? How does a space transform into something that serves the needs of the future? An industry practice that answers this challenge is adaptive reuse. Across Ontario, there are hundreds of adaptively reused buildings and spaces that operate differently from what was originally intended while retaining historical features. Toronto’s Evergreen Brickworks was originally a brick factory but today operates as a community space. The Thunder Bay District Courthouse now operates as a hotel. And the Ontario Heritage Centre, built in Toronto in 1909 as an investments and savings company, now serves as the headquarters for the Ontario Heritage Trust. It is one of the many adaptively reused buildings in the Trust’s portfolio.

How one defines adaptive reuse is often up to each person’s interpretation. It is a concept that is central in the building and architectural industries. Working alongside stakeholders and industry professionals, the Trust operates as a knowledge sharer to provide expertise and information about adaptive reuse and its practices.

"Adaptive reuse can be defined as what the term states: to revise the original intended use of a structure by adapting it for reuse," says Heritage Architect Leroy Shum. The concept takes an existing building or structure and, instead of demolishing it, reuses it for a new purpose. The fabric (the structure or key features of a space) remains strong, but the space is adapted for a new purpose. Adaptive reuse acts as a conservation exercise, protecting both the fabric of buildings and preserving the intangible heritage skills and techniques that went into the creation of the original space.

What goes into adaptive reuse?

Adaptive reuse is comprehensive, but there are some key points and processes that stand out. When it comes to starting an adaptive reuse project, the planning and assessment is a significant first step. Before acting, it is imperative to assess a property and bring in the proper experts and stakeholders to ensure that this method is the right pathway for that space and ensures the most success.

“Good adaptive reuse solutions are ones that are well thought out,” says Shum. “Depending on the situation, certain experts are brought in to formulate a solution to a problem. Architecturally, there are many external stakeholders involved in the course. Much like creating a business plan.”

Pulling apart the process before it even begins is essential to a successful project. There are a multitude of factors to consider when planning and implementing an adaptive reuse solution. Some key factors include:

- the environmental impacts

- the conservation of key elements of a building

- the interpretation of a space

Environmental impacts

When deciding whether to demolish a building or convert it using adaptive reuse principles, considering the environmental impacts of both processes is essential. The demolition of physical structures has environmental repercussions. “When assessing a building, you need to understand how much negative impact would be incurred based on the intended proposals.” added Shum. “If you break the process down, you think about demolition, you equate that to landfill, increased carbon emissions and, ultimately, waste.”

Environmental awareness is at the core of adaptive reuse — but so are the awareness and sensitivities surrounding the preservation of the original design and building fabric that have been cared for through maintenance and monitoring by staff and skilled labourers over time.

Conservation

Conservation is a key factor to any adaptive reuse project. While environmental impacts assess the broader space, looking at conservation can point to more specific parts of a building. “We focus on the retainment of existing fabric to be reused in a different way,” says Shum. “Some fabric is integral, particularly important to the interpretation of some of the properties. So, there are certain strategies we use to retain that." Deciding what needs to be conserved versus what can be adapted for a more relevant or current use is a vital part of the process. As a part of conservation and the deciding factors of choosing which fabric to conserve or not, there is the importance of continuing the interpretation of the space.

Interpretation

“With each building, whether it be modern or culturally sensitive, there is an interpretive element to it,” Shum says. “There is a timeline that tells a story.” Mapping out the history of a building and conserving the elements that hold that historical significance is how interpretation of spaces is created. When it comes to interpretation and the storytelling of the building, it is important to know “this is what it was then, this is what it is now, and these are the decisions made along the way.” This principle answers the “why” questions. Why is the building being adaptively reused? Why are certain fabric elements conserved over others? Why does the history of this building matter? These questions help build the story of space: the interpretation.

Maintaining the interpretation of the space is imperative to what adaptive reuse is. Shum emphasizes the importance of being aware of what impact we have on sites, properties and spaces based on the decisions moving forward. This awareness is necessary in the case of interpretation. Once significant, meaningful fabric or an item of focus is lost, it is lost forever.

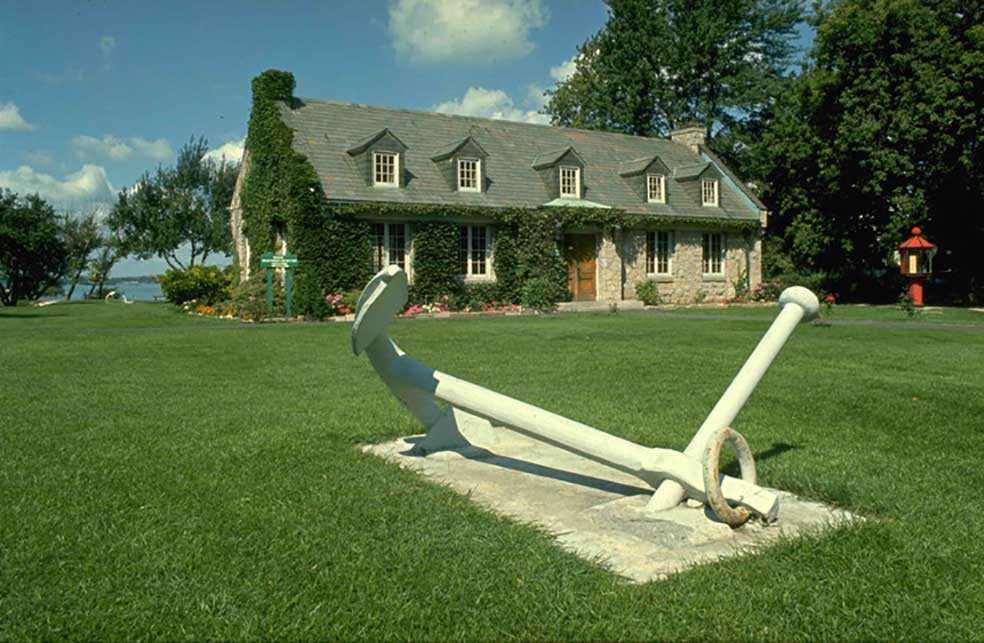

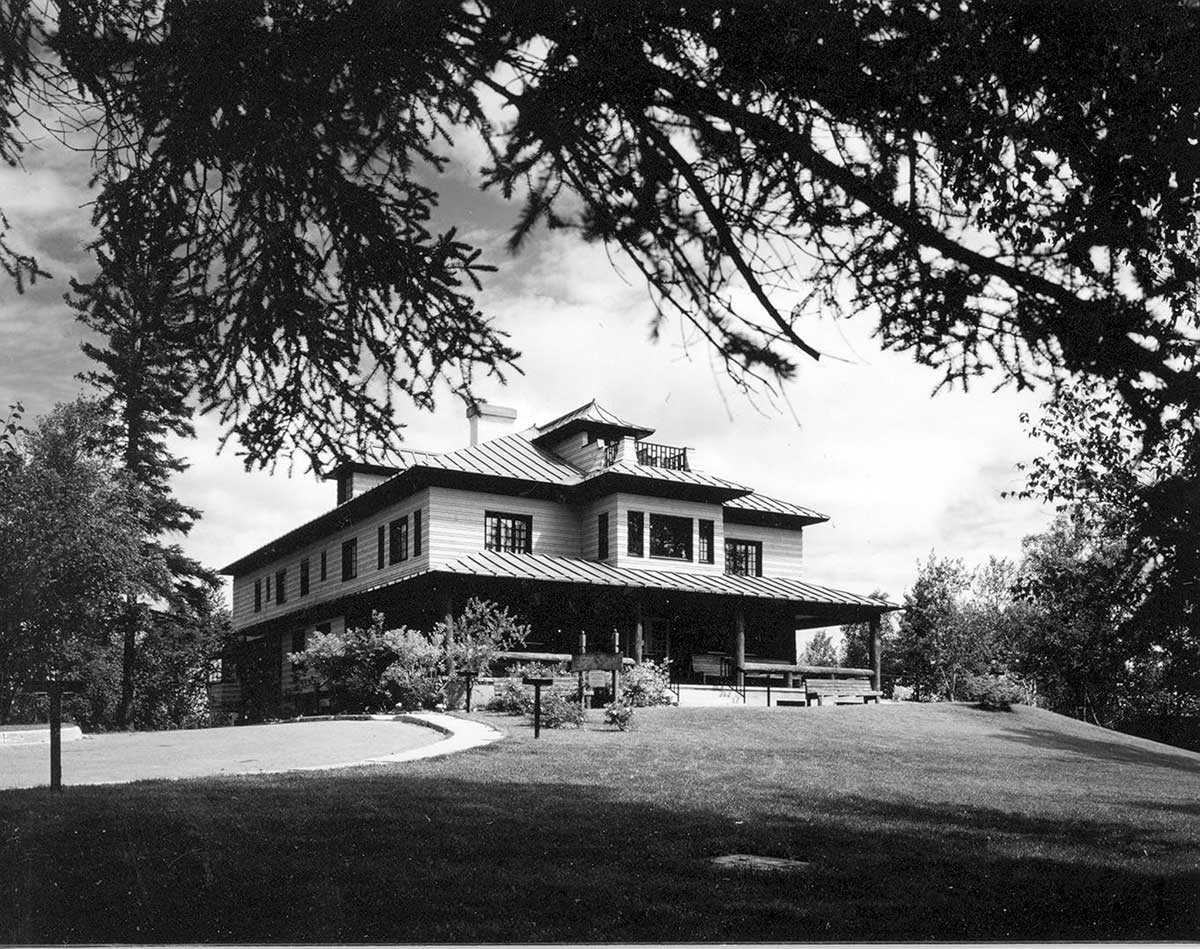

Exploring an adaptive reuse case study: Fool’s Paradise

The Ontario Heritage Trust holds several examples of successful adaptive reuse projects in its built portfolio. Located in Scarborough, Fool’s Paradise is a small house located on the edge of the Scarborough Bluffs. The house was once the residence of Doris McCarthy, a renowned Canadian artist and painter. In 1986, McCarthy donated the 2.8-hectare (7-acre) property to the Ontario Heritage Trust. In 2010, the Trust reused the space and converted it into the Doris McCarthy Artist-in-Residence Program. “It was a private residence, but it was the wish of Doris McCarthy that it would become an incubator for the arts,” says Shum. The program being run out of this space currently hosts multiple artists each year who can create their artwork while living at McCarthy’s former home and studio. While the structure remains the same, the use of the space has changed to welcome artists and preserve artifacts from McCarthy’s life. It is important to the interpretation of the space that the legacy of Doris McCarthy lives on through the program. The site has transformed in a way that is more relevant today and serves the needs of more people. The fabric elements of the house are conserved to ensure that the artists experience what McCarthy once felt while making her own creations there.

Conclusion

Adaptive reuse is the process of taking a space, assessing the needs of the community, identifying a new purpose, and transforming it into something new. This concept has been explored through the lens of architecture and buildings. But it begs the question: can adaptive reuse apply to more than just buildings and structures? If a building can adapt and change its original intended use into something else, why can’t other spaces? "If we talk more about natural or cultural landscapes, then we would have a lot more questions and considerations to make,” says Shum. Applying adaptive reuse principles to other spaces and landscapes would need a change in its process, a careful rethink. But this does not mean it cannot happen. In fact, it’s more imperative than ever that we consider how all spaces — including cultural and natural spaces — can adapt and change to suit modern needs.