Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

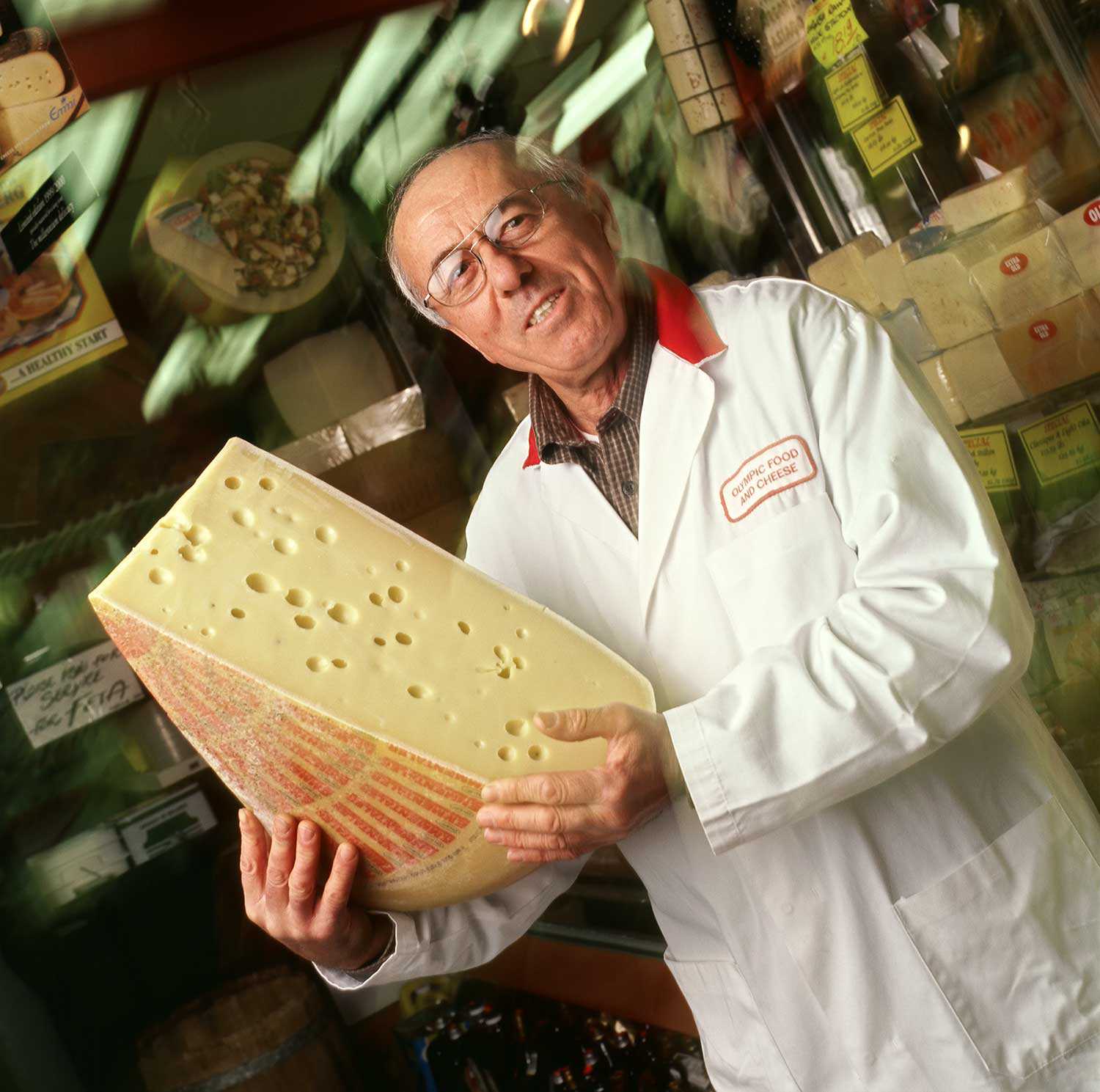

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Conserving what we value

Published Date: 01 Oct 2019

It was my time to finally get my message across.

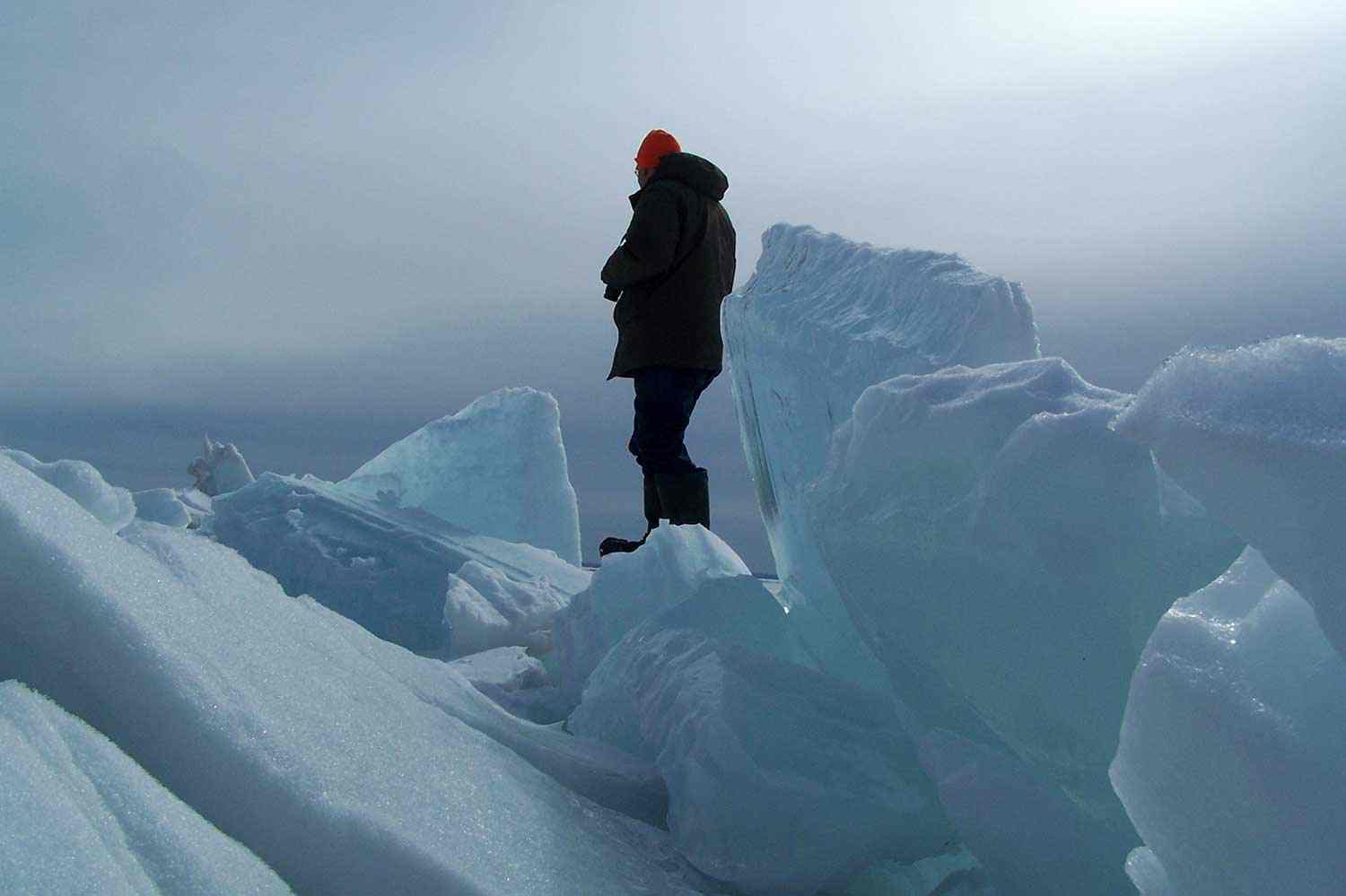

About 15 years ago, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) was beginning to purchase properties on Pelee Island. The community, however, was uncertain about conservation – uncertain about what potential changes it would bring.

The NCC had retained the help of a stakeholder consultant. He brought many key community members together – including the mayor, councillors and farmers to tour a property that the NCC hoped to purchase. I was asked to share why we wanted to conserve this, and more properties, and why it was important.

Dan Kraus is a Senior Conservation Biologist with the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

This was my chance. I explained how the property was part of a provincial Area of Natural and Scientific Interest, how it had rare alvars with vegetation communities that had been ranked as globally rare by NatureServe, the many species that were nationally at risk, and how it was an Important Bird Area for migrants that rivaled Point Pelee for species richness and abundance. I explained the post-glacial biogeography of the island – how it has once been connected to the mainland, and that many of the plants and animals would never occur again if they were lost. How wetlands and other habitats found on the island were becoming very rare in southern Ontario, and needed urgent protection.

I finally took a breath. This was going great. I was giving myself goosebumps.

Then, I looked around – at blank faces. For a fleeting moment I thought: they finally get it.

My self-delusion was broken when our community consultant looked at me and said something that I’ll never forget. Something that has forever changed how I think about conservation.

“Now, can you explain why it’s important for them?”

As a scientist, I think about nature and our work at NCC through the lens of conservation biology – through a discipline that sees a world of rare species, wildlife connectivity and optimal reserve design. It’s a useful and important lens. In a country that has almost 800 species at risk and has many habitats that are rapidly declining, we need good science to help identify and direct where we invest in conservation.

I once believed my science was conservation. I assumed science is the why of conservation and that nature conservation is science-based. But science actually does not fully address why we want to protect nature. It simply creates and gathers information to help us do conservation. The deeper questions of why – why do we protect nature? why do we care? – stem from our values.

And all of the conservation work we do is ultimately value-based.

I deeply value rare species and wetlands in places like Pelee Island for their intrinsic values. I think they are incredibly interesting and that we have a responsibility to protect them. And I tend to surround myself with people who share these values. But this is just one way to value nature. People that don’t seem to care about rare species and wetlands often still value nature. They just value nature in a different way.

There are now many ways to describe how people value nature. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Ecosystems and human well-being: A framework for assessment. Report of the Conceptual Framework Working Group of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2003), was one of the first reports to describe the goods and services that people get from nature. It identifies 24 services in three main categories: provisioning (e.g., drinking water), regulating (e.g., erosion control) and cultural (e.g., how I really like rare species).

Economists have even started to put a dollar value on these goods and services. While the ecologist in me originally feared that economic valuation as perhaps a capitalist plot to commodify nature, I’ve changed my mind. Economists recognize that there are some goods and services that we cannot put a dollar value on. When numbers are applied to these select goods and services, they are very high, and can actually help to illuminate better the immense value of nature.

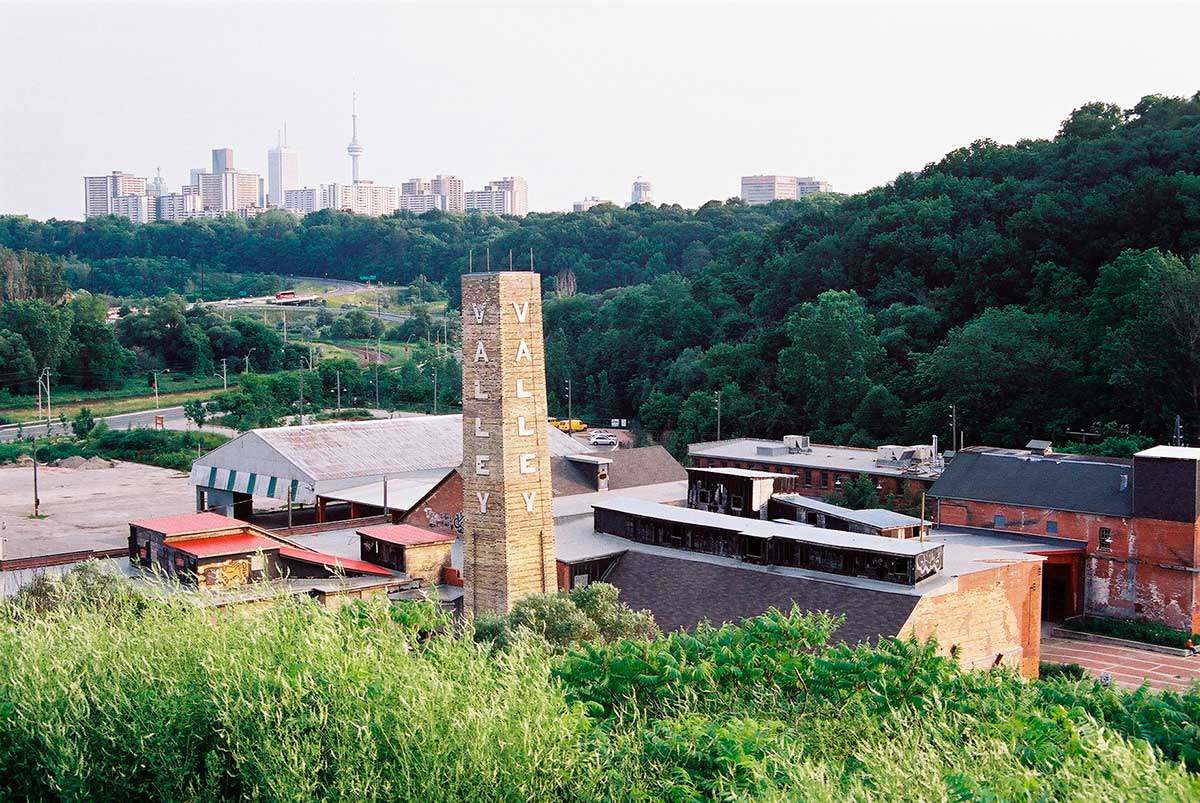

A hectare of Great Lake forest can provide $20,000 of ecological services each year (based on a study done by TD Economics and the NCC), and this does not include many services such as recreation, tourism or the biodiversity that this forest supports. The trees in the City of Toronto’s urban forest are worth an estimated $7 billion (as per TD Economics, Urban Forests: The Value of Trees in the City of Toronto. 2014).

Even with the limitations of economic valuation, these are big numbers. It’s becoming increasingly clear that we can’t afford to lose the benefits they provide.

A diverse Canadian society needs us to develop diverse ways to describe the benefits of nature. This doesn’t mean abandoning the intrinsic values of nature – the so-called cultural services that nature provides. As conservationists, we absolutely need to express why we value nature. Our passion and commitment will inspire a few others to love what we love. But we also need to listen and learn about how other people value nature, to become nimble in understanding and translating why nature is important for everyone.

If we simply insist that all people value nature in the same way that we do, we are missing an opportunity to broaden our own understanding of the values of nature. At worst, a values high-ground can fuel division and thwart opportunities that could spark new collaborative approaches to advance the conservation work so desperately needed by our communities, country and planet.

Nature conservation is ultimately about people. Science is doing a good job in identifying what we need to protect, and where we need to focus our actions. My office is filled with lists of rare species and maps of priority places. But the Holy Grail of conservation is not more information on what to do; it’s creating a society where people value and want to conserve nature.

It wasn’t until I listened that I realized what my response should have been that day on Pelee Island.

I should have asked why they care about Pelee Island. I would have learned that they were fiercely proud of the unique character of the island and that they had conserved species that had been lost from government-protected areas on the mainland. That they were concerned about a lack of job opportunities for their children, and recognized the need to diversify the agricultural economy through eco-tourism. They were worried about water quality. They wanted a voice in what was protected and how it was managed.

We shared many of the same values. I just didn’t take the time to listen.