Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

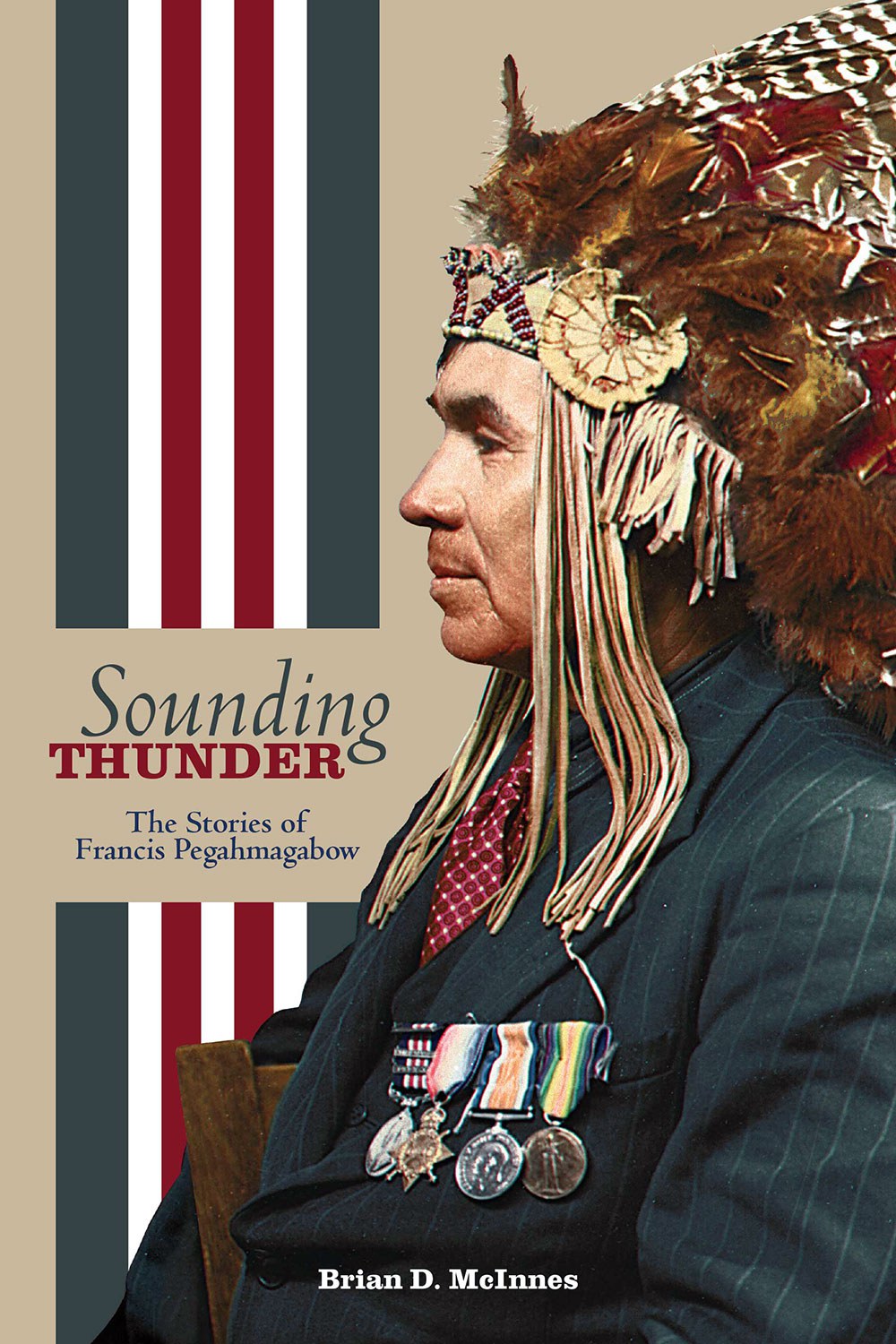

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Clay connection – Indigenous living and creativity

"When we move our feet in harmony with that beat, we are literally and figuratively moving in harmony with the heartbeat of the earth."

Rick Hill

A couple of decades ago, I witnessed a friendly debate between a white historian and an Indigenous ethnologist. The well known historian, who just happened to look like United States General George Armstrong Custer, was going on about rigorous scholarship, professional ethics and how historians had to consider both the emic (from within) and etic (from without) points of view when writing on Indigenous history. Growing a bit impatient, the Indigenous scholar told the historian to get out of the library and into the community where the real culture existed. The Custer look-alike stiffened, tilted his head back and stated, “I will have you know, the library is my culture.”

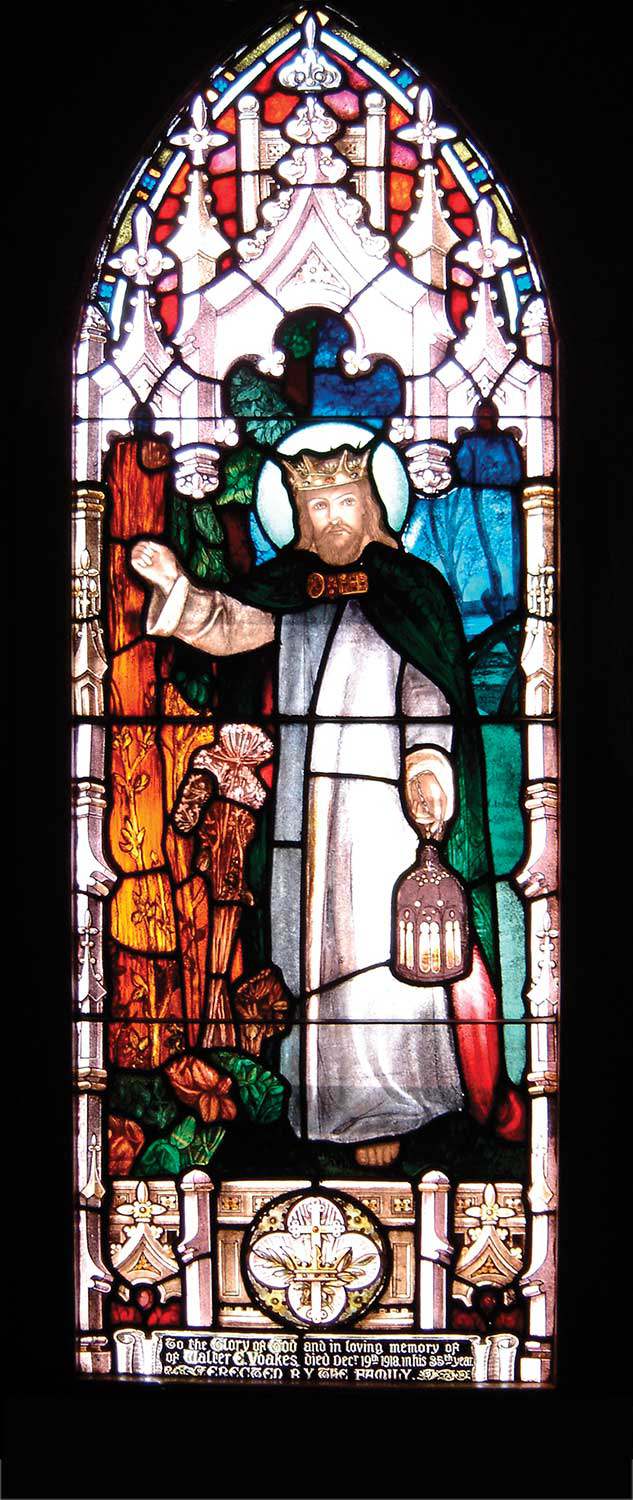

The audience roared their approval and some laughed at this ironic polarity regarding knowledge that their debate highlighted. It seemed all too perfect. North Americans have their libraries, art galleries, museums and universities as the keepers of their collective knowledge. Indigenous peoples have their oral traditions, customary practices, belief systems and traditional arts, and make personal memory the keeper of the knowledge for their societies. Never the twain shall meet.

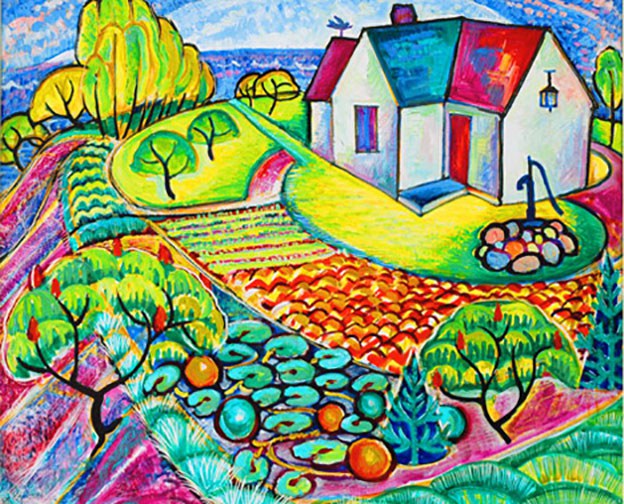

Sometimes we think of art as a tangible manifestation of culture. Societies make things to give evidence of collective identity or individual reaction to collectivity. We tend to think of these creations as material culture, to distinguish them from the fine arts. We also tend to think of philosophy, rhetoric and knowledge as intangible aspects of a culture. This we refer to as intellectual or cultural property. Both forms of cultural expression are important in shaping our worldviews, identities and perhaps destinies.

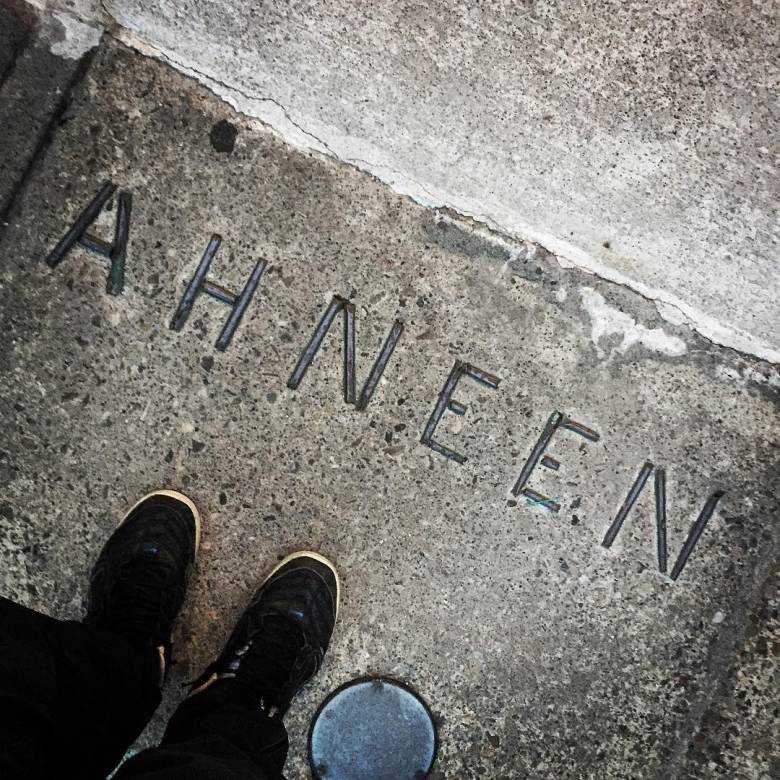

When the Mohawks first greet each other, what they say loosely translates to “What kind of clay are you made from?” It really means, “Where are you from?” However, since the Mohawk Creation Story tells of the first humans being made from the clay of the earth, this greeting has a deeper meaning. It acknowledges the Creation Story.

In response, one might say, “I am of the Wolf-kind of clay of the Mohawk valley.” This means they are of the wolf clan, as compared to the bear and turtle clans of the Mohawk Nation. It also means that Mohawks of today are genetically linked to the clay where their ancestors first roamed – the Mohawk Valley near Albany, New York. Further, it means that since Mohawk ancestors have been buried in the loving arms of the Mother Earth for centuries, clay is really the recycled remains of all that once lived here before. Human flesh decays and becomes soil and clay. All that lives becomes fuel for the spirit of the earth.

So, when Mohawk artisans took a lump of clay from the ground and shaped it into a ceramic vessel to be used as a cooking pot, they held in their hands the ‘living’ earth. It is malleable. It transforms itself with the gentle hand of the maker. The ceramic pot is therefore like a distant relative, reborn into a utilitarian object. It is an entirely different notion about how ancestral knowledge fuels our vitality. Their flesh becomes the earth. The earth produces clay. Clay becomes a container. The container is used to prepare food. Humans are nourished by the food and the minerals in the clay in which food is cooked. In case you were going there, it is not a form of cannibalism! It is recycling the energy of our ancestors.

What makes humans different from an earthen jar is that the Creator gave us a part of his living breath. That is what animated our bodies. It also allowed us to be able to think, to feel and to create, and to visualize the unseen aspects of the Creation.

This does not mean that the ceramic pot is ‘dead.’ Far from it. It has its own kind of life force – a living spirit that can communicate with those who are ready. However, it cannot recreate itself, or modify its form. However, it can stimulate the human mind to do that very thing. Old art inspires new forms. The clay pot exists as itself. It manifested its destiny with the helping hands of the person who made it. It was a collaboration between the human and the earth.

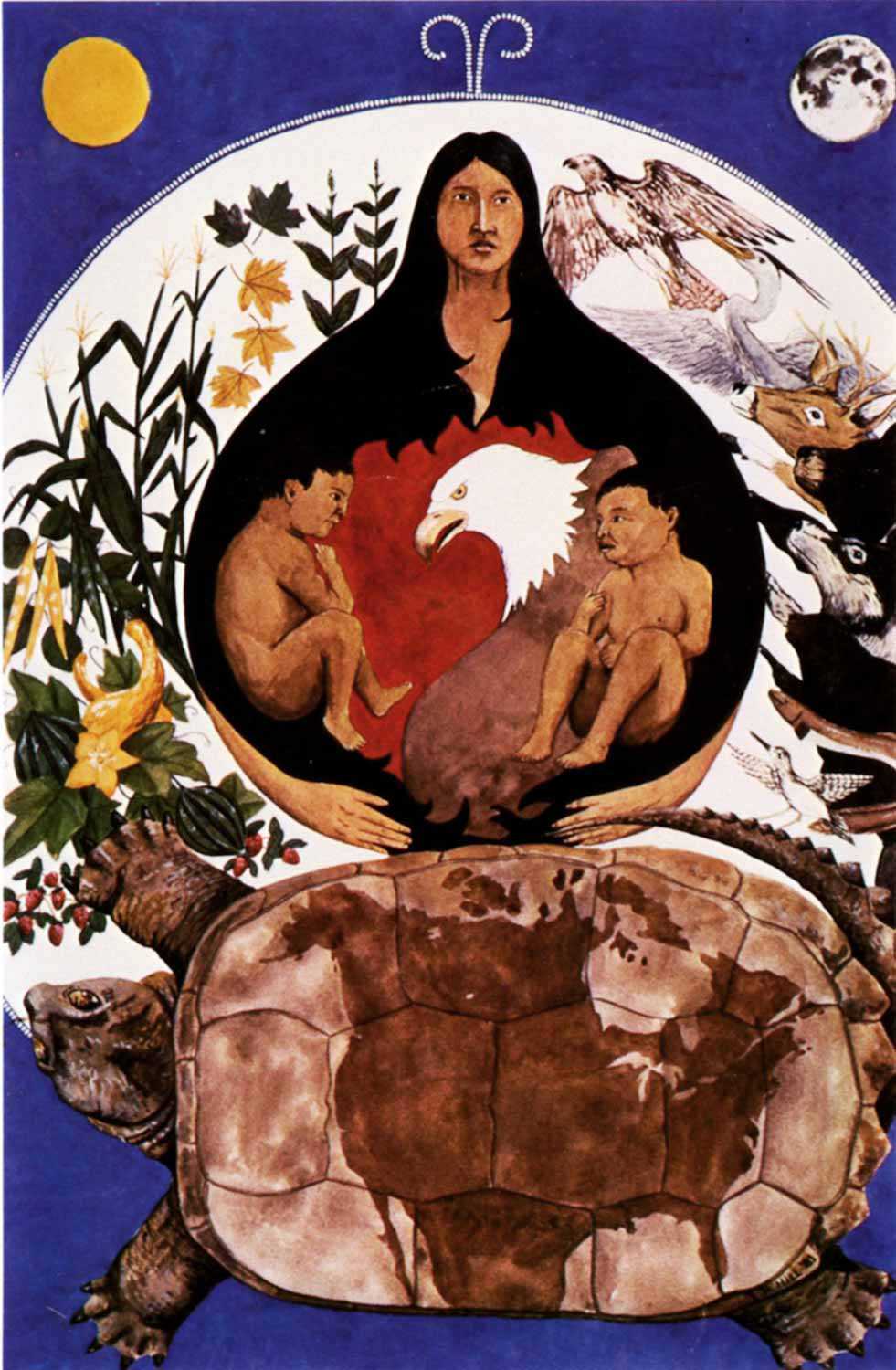

Haudenosaunee oral traditions tell of an important moment when the world was being created. A pregnant woman fell from the sky and was placed on the back of a giant turtle. A tiny muskrat dove to the bottom of the ocean to retrieve a small pawful of mud. When that mud was placed on the back of the turtle, magic took over. It began to grow.

The Sky Woman began to dance in a counterclockwise circle, shuffling her feet in such a way that flattened and widened the clay underneath, eventually to form the shape that we call the Great Turtle Island, which would later become the Mother Earth from which humans, along with all of the plants, birds, animals, trees and medicines, were also made.

When we hold ceremonial dances today, we dance in the same direction that Sky Woman first travelled on the Turtle Island. To give thanks, we relive the Creation with our dances, the most sacred of them to the beat of a rattle made from the carcass of snapping turtle, itself a symbol of the earth. When we move our feet in harmony with that beat, we are literally and figuratively moving in harmony with the heartbeat of the earth. It is difficult to describe what it is like to be in the middle of rows of dancers, with singers in the inside, a row or two of women dancing the same way that Sky Woman made the Turtle Island, and rows of men on the outside, with children interspersed throughout.

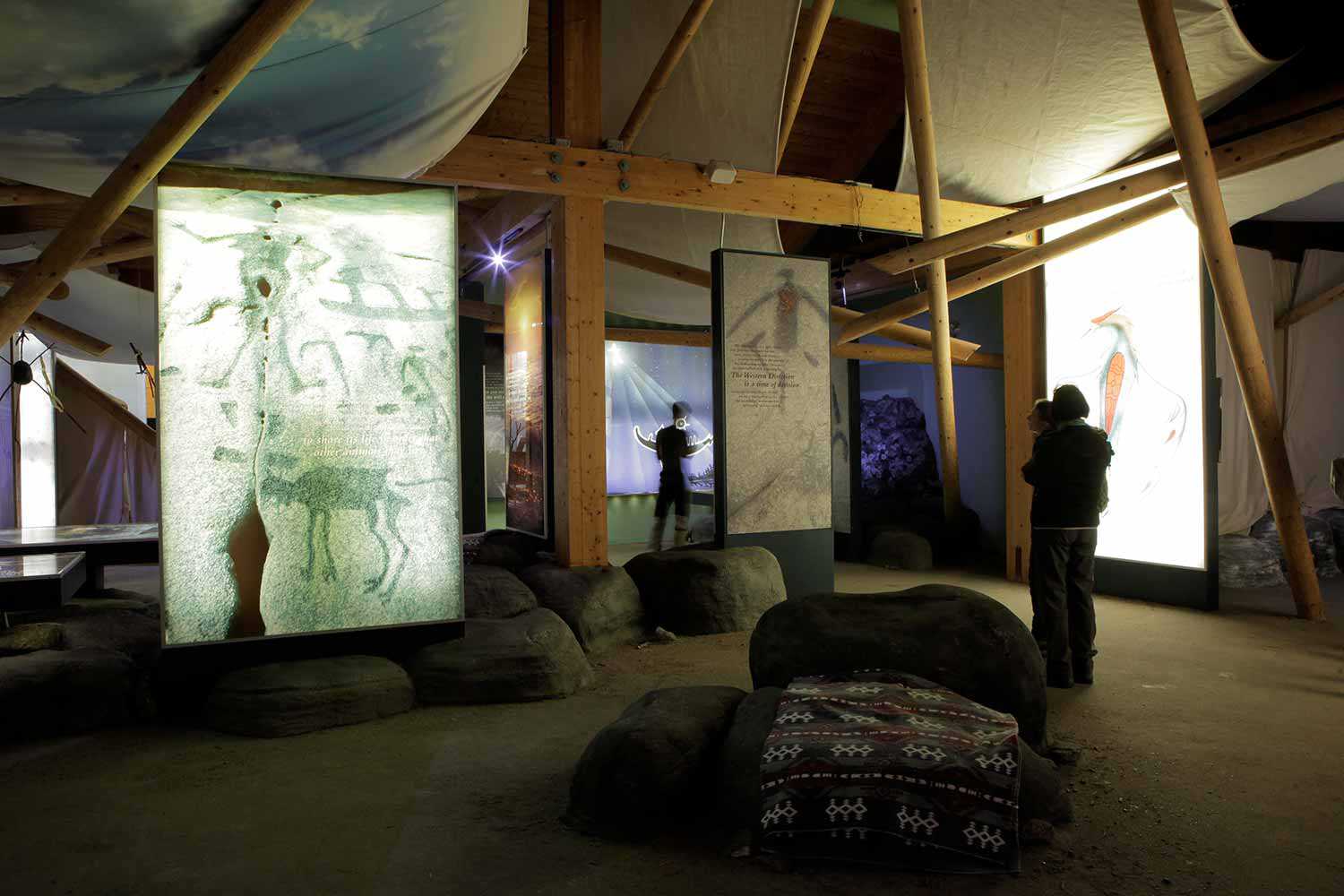

Everyone has brought their hearts and minds together to bundle our thankfulness in a great dance. You feel the connection to the ancestors, who also did the same dance, the countless generations of singers who sang the same songs, and a deep connection to what makes the Creation a sacred place. All seem to be present in these dances. It is something that no painting, no sculpture, no video or no essay can capture respectfully.

You have to be there and be part of it to know what it is. When we dance, we are instructed to dress in our most beautiful clothes. It is amazing to see women literally wrapped in their culture. They bead symbolic designs of their Creation on their wraparound skirts. It is here that verbal culture and visual culture come together. The tiny beaded designs are like a cosmogram – a graphic depiction of our universe. By seeing the symbols, you reaffirm your understanding of your being.

Certainly, some of the beadwork is more expertly crafted, some more intricately depicted. Some with more harmonious colors. No two are alike. Yet, they all make up one large narrative. In that moment of the dance, the differences in beadwork do not matter. It is how they look as they move in the dance circle that matters. They exist for that moment, come alive during the song, then slowly settle back into their more static form. Just like the annual cycles of nature. The same happens with the split feathers on the men’s headdress, called a gustoweh. The striped turkey, hawk and eagle feathers flutter in a special way when the men dance. The large upstanding eagle feathers twirl as if they are birds circling about. As the men move their shoulders and heads, the feathers react and seem to have a dance of their own.

For a brief moment, all seems to be perfect. You don’t want the dance to end. Its vibration stirs our hearts and unites our spirits. For one moment, we truly understand what it means to be Haudenosaunee. Then we get in our cars and go back to our single-family homes. Back to our jobs and secular life. Back to school or back to the protest. Yet, we carry the memory of that moment. We carry the memory of our ancestors. We carry the memory of our Mother, the earth. The memory of beads and the memory of feathers. That is what sustains us through the rest of our non-Indigenous lifestyle. We are thankful for those moments of clarity.

![Rose Lieberman, Rose [Hanford?] Green and Aaron and Sarah Ladovsky in front of United Bakers restaurant, Spadina Ave., Toronto, 1920. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, fonds 83, file 9, item 16.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/SoupsOn_Archival_3505.jpg)