Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Bkejwanong: Sustaining a 6,000-year-old conservation legacy

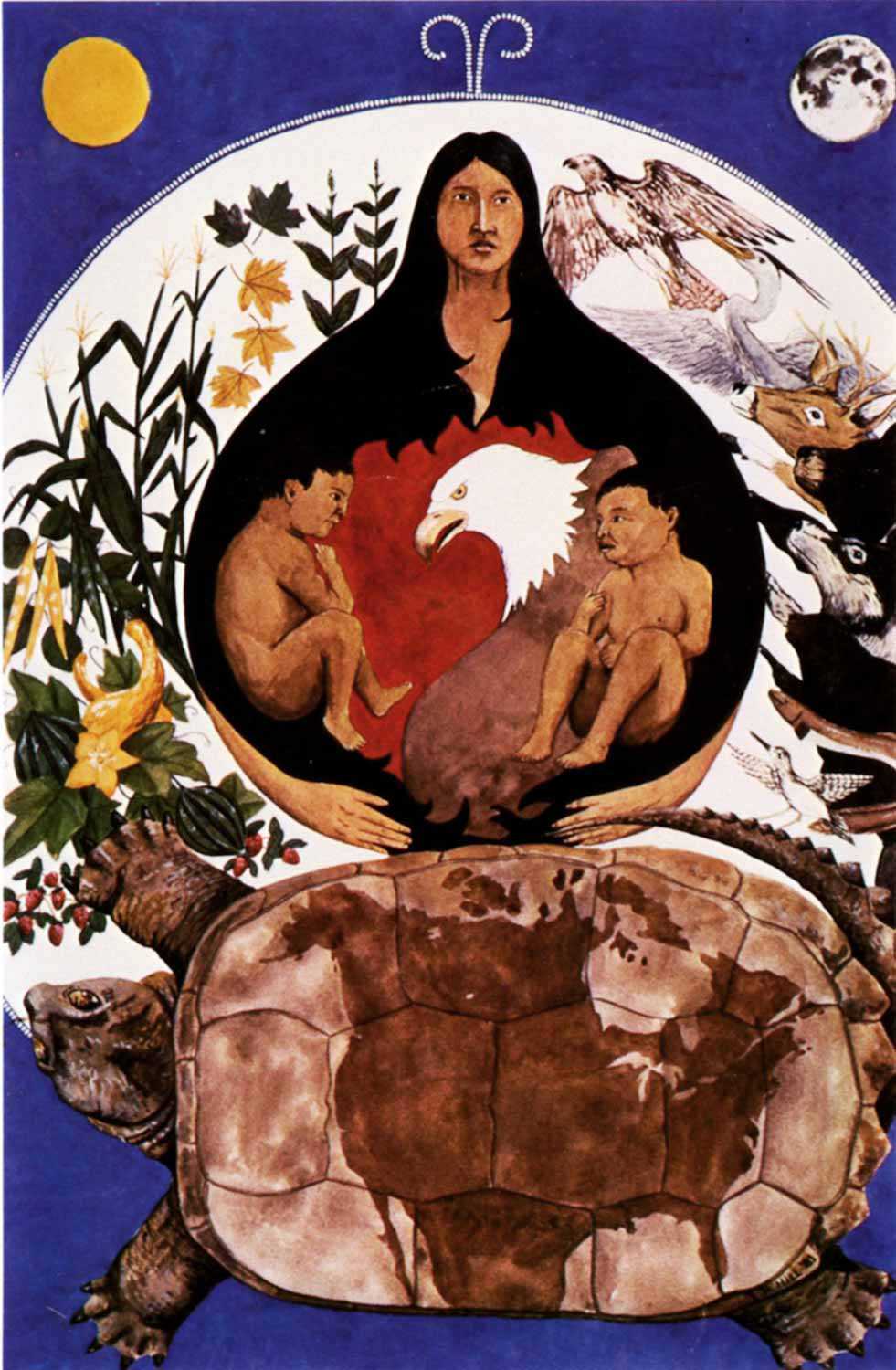

Nestled at the mouth of the St. Clair River on Lake St. Clair in southwestern Ontario is the Walpole Island First Nation or “Bkejwanong,” meaning “where the waters divide” in Ojibwe. A legacy of conservation practices cultivated by my people, the Anishnaabe (Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Odawa tribes) has ensured that the land remains remarkably alive with natural wonder.

Throughout the approximately 6,000 years that my people have lived at Bkejwanong, we have been dependent on Aki, the Earth. The land took care of us; in turn, we were taught that we had the responsibility to reciprocate that care. Land stewardship was instilled in our children through traditional teachings. Families would harvest materials, medicines and food from the land in a sustainable way to ensure that those gifts were available for future harvests and generations to come.

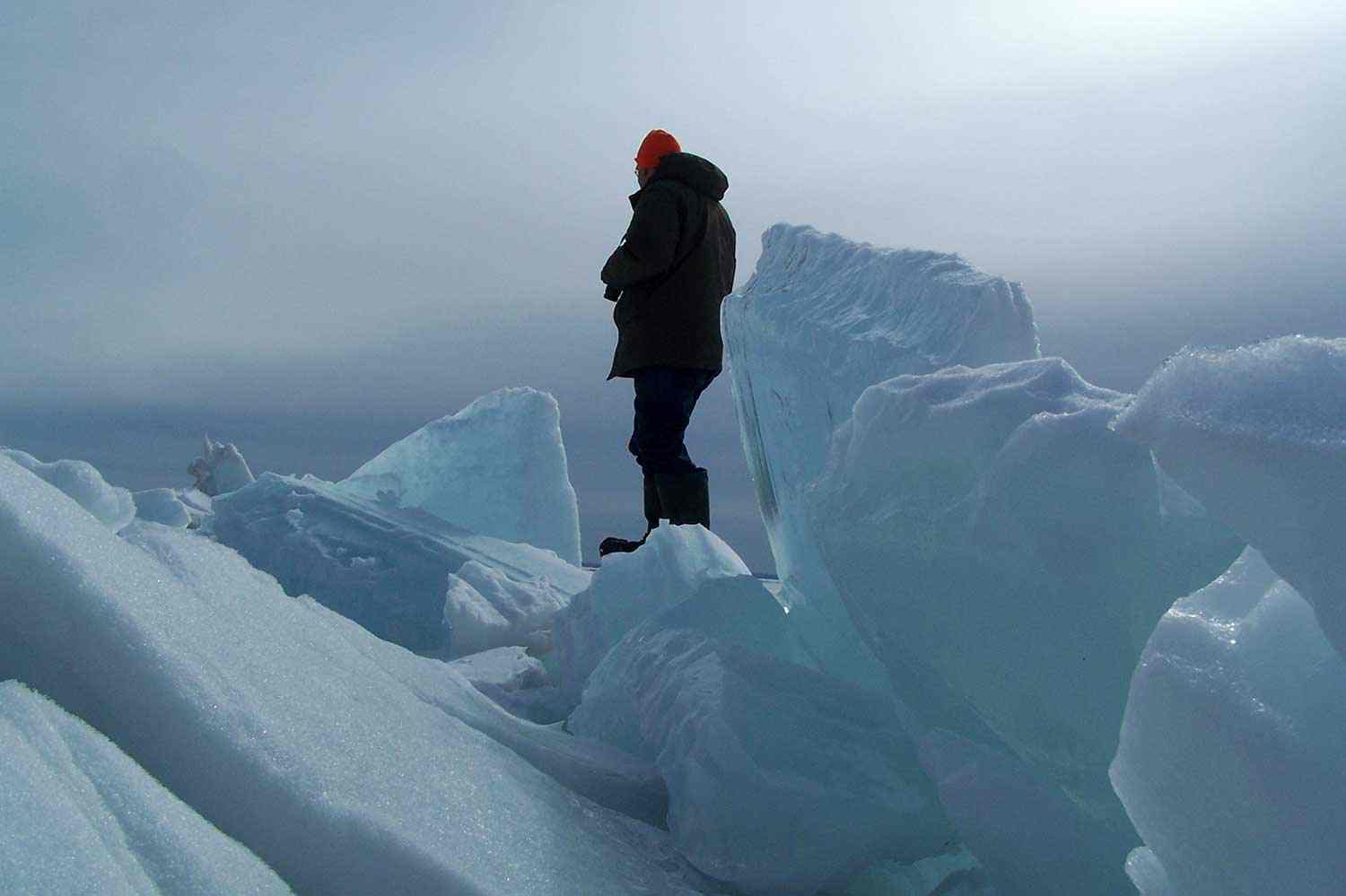

Today, our community boasts a unique natural heritage of world-class wetlands, Carolinian forests and rare oak savannas and tallgrass prairies – including over 60 of Canada’s rare and endangered species, some found nowhere else in Canada. With a population of just over 4,000, we have successfully shared our territory for millennia with a diversity of species such as small white lady’s slipper, Kentucky coffee-tree, sassafras, dense blazingstar, king rail, spotted turtle and flying squirrel.

During the last century, however, our relationship with the land has eroded. The traditional practice of passing knowledge from elder to youth has been disrupted because of the residential school legacy, technology and modern conveniences that have damaged our symbiotic relationship with the environment. The cultural values and ecological knowledge that have safeguarded our land for millennia are in danger of disappearing.

As a growing community with an historic cultural legacy tied to our ancestral home, how do we continue to protect and sustain our natural heritage in the face of modern social and economic pressures? This is a question we have been actively addressing as a community for decades through the work of the Walpole Island Heritage Centre and other grassroots initiatives.

Hummingbird banding demonstration by the Native Territories Avian Research Project (NTARP) (Photo: Carl Pascoe)

More recently, Anishnaabe-speaking community members and language learners are in the process of integrating our legends and stories into school curriculum and language immersion programs to foster and enable bilingualism. Further, our youth are becoming involved in conservation through the Bkejwanong Eco-Keepers youth environmental stewardship program, providing summer students with opportunities to work on stewardship projects, many of which they design themselves. This teaches conservation ethics and enhances cultural ties to the land, while exposing the students to a range of career opportunities within the environmental field. As well, our new energy conservation office educates community members on how to reduce energy use and eliminate greenhouse gases.

Partnering with groups and individuals outside the community is another important part of our conservation approach. We have shared and exchanged experiences with people across North America and beyond. For example, in partnership with the Native Territories Avian Research Project, we are creating hummingbird, songbird and owl banding programs in collaboration with Six Nations Territory and the Chippewas of the Thames to provide bird studies education and training opportunities.

Our community recently celebrated a milestone – the creation of Canada’s first registered Aboriginal land trust, the Walpole Island Land Trust, which aims to integrate formal land conservation with traditional cultural ties to the land. In addition to several tallgrass prairie conservation and stewardship projects (thanks to the generous support of corporate and conservation sponsors), we are also conserving and restoring a 171-acre/69-hectare marsh on Walpole Island with a number of local partners.

Tallgrass prairie is a globally imperiled ecosystem that provides habitat for many species at risk, such as the endangered bobwhite quail. Funds raised for these habitats will also support ecological restoration, research, training and community initiatives that will teach our children sustainable methods of harvesting food and medicine. Youth will be mentored by elders to learn ethical hunting practices, survival techniques and stories that relate our historical relationship with the land – ensuring that they know how to live on, and protect, our territory.

By pursuing natural heritage protection while working as a community to promote and maintain our relationship with the land, our rich biodiversity can share a prosperous future with my people. Simultaneously, it encourages us to look to the future as our elders and ancestors did, a philosophy that has supported my people for more than 6,000 years. We owe it to our ancestors and all our relations – the plants and animals – to sustain our conservation legacy.