Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

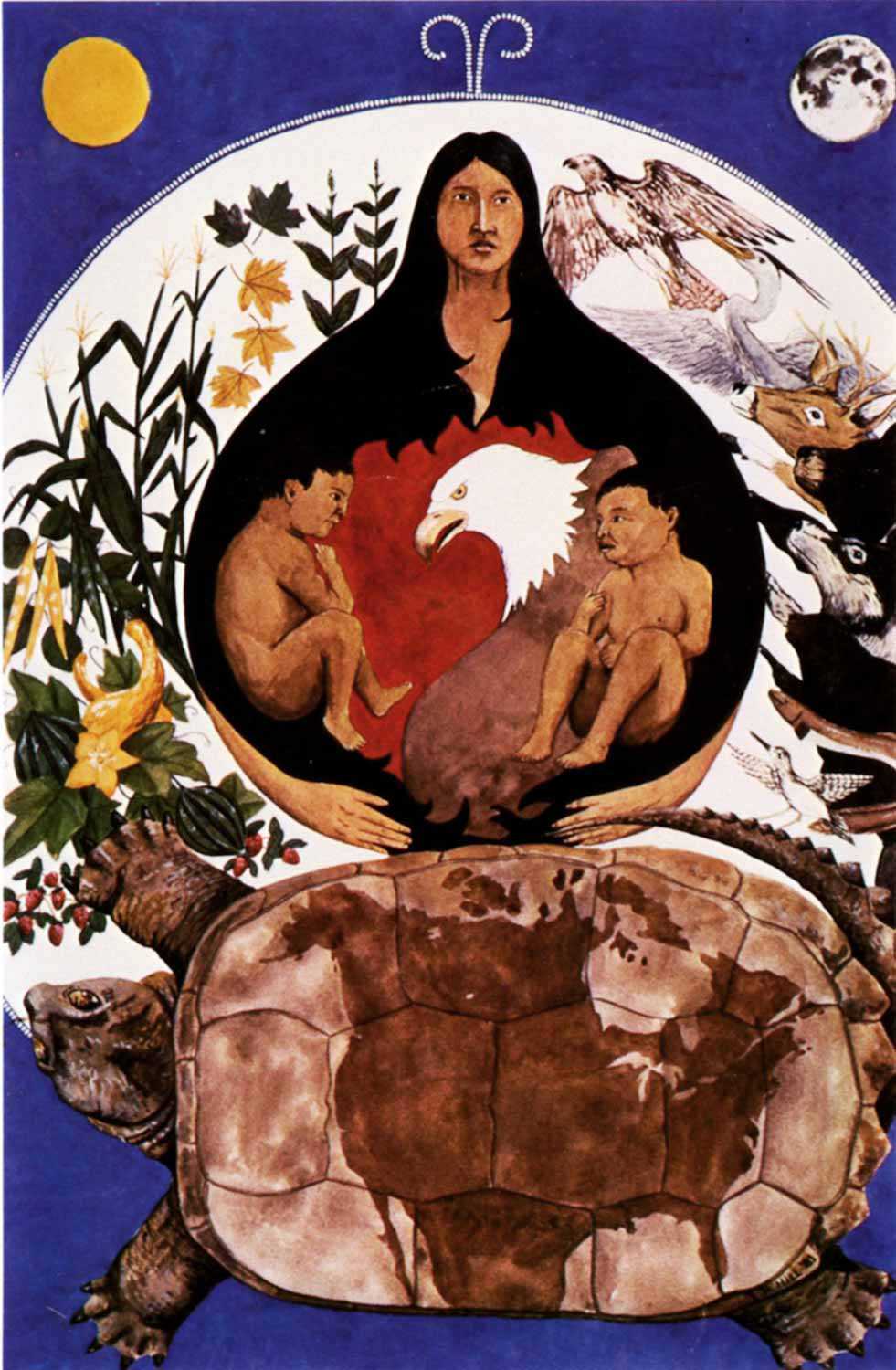

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

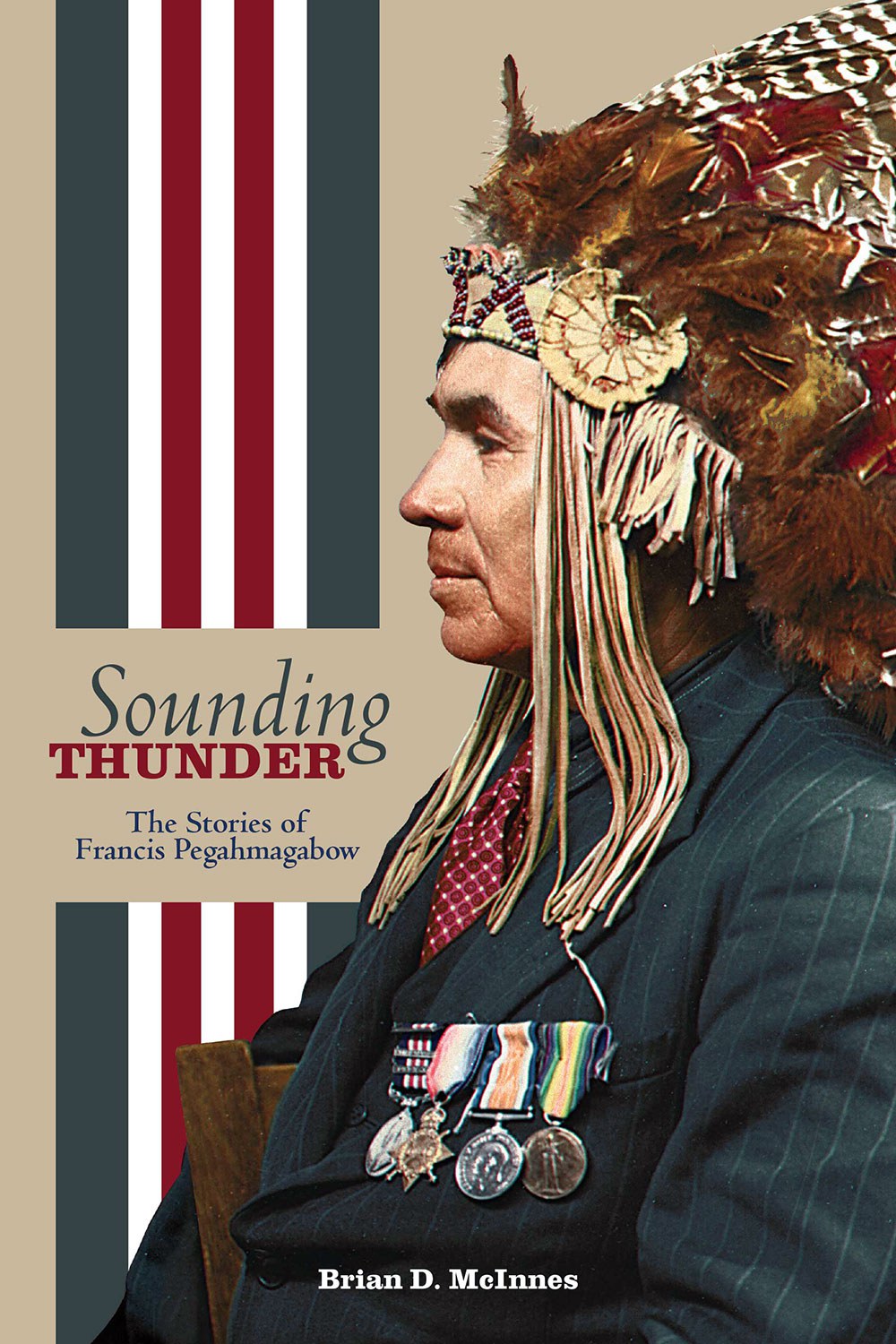

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

The intangibility of our digital worlds

"More and more, our stories are captured and experienced – sometimes entirely – in virtual space. It’s the very definition of intangible."

When was the last time you printed your photographs or made a photo album that you could hold in your hands? It’s probably been a while.

But you’re likely documenting your life with digital images regularly. The average iPhone user takes about 150 pictures a month. It could be phone pics of your son dancing at Grand Entry during the annual pow wow. Or GIFs of you taste-testing at last weekend’s community butter tart festival. Or perhaps you’re taking in a virtual reality installation at your nearby art gallery. There’s no question that Ontarians, like the rest of the planet, have become a digital species. More and more, our stories are captured and experienced – sometimes entirely – in virtual space. It’s the very definition of intangible.

Digital culture is not only intangible, but digital tools are also great for documenting intangible heritage.

The simple family photograph is a great metaphor for this digital shift. Instead of printing hard copies of our pics, we are storing years and years’ worth of them on our devices, our hard drives, sometimes up on the cloud, and sharing them with our communities over Facebook, email, Instagram and other forms of social media. Most of them never materialize on paper or in a picture frame on our wall.

So what happens to these pics – these memories – when our devices break down, or when we lose our hard drive? Or when Facebook or YouTube changes its policies? And who owns the servers that our photographs are stored on? Are we caring enough about how to preserve these digital stories, these family albums, for future generations? Or even for next year?

It’s not just personal. Ontarians of all walks of life use digital tools to capture, share and preserve our collective intangible cultures, including food, dance and oral traditions. Community groups on Facebook, bloggers, Instagrammers and YouTubers are all documenting and sharing stories of identity. For example, Ontario’s top farming Instagrammers document the province’s extraordinary bounty and food culture. Ottawa-based Garnement Inc. is a group of young Franco-Ontarian comedians sharing laughs and culture on a YouTube channel. The connections between participatory culture and social media are strong. Just this summer, Toronto’s Caribana festival has been renamed and rebranded as the Peeks Toronto Caribbean Festival, because its new major sponsor is Peeks, a mobile livestreaming app. It’s not hard to imagine the possibilities of kaleidoscopic citizen-livestreaming from such a spectacular event. Food, festivals and oral traditions are a great match for participatory and sharing digital tools.

It’s not just our personal artifacts of photos, videos and music. Our professional, collective cultural creation is increasingly digital, and those projects themselves become “intangible.” Often these projects have no physical manifestations at all. I’ve been making contemporary documentaries exclusively native to the web for over 15 years, as have so many artists working with cutting edge digital tools to make video games, apps, interactive and immersive projects and, now, virtual reality installations. In fact, Ontarians produced one of the earliest major breakout video games back in 1983 called Boulderdash. Across the province, we’re seeing virtual reality and augmented reality come alive in museums and galleries. In London, the Ontario Museum of Archaeology houses a virtual reality exhibit of an Iroquois longhouse. In Ottawa, the Science and Technology Museum is getting a major renovation, which will include a virtual reality arcade to showcase the entire archive. When physical space is limited, virtual reality can help with access.

For the last 15 years, huge efforts have been made to digitize archives, cultural collections in museums and local libraries. By digitizing, we are hoping to both safeguard and conserve work. It’s also an effort to make work more accessible to more people, often online. Large national projects around the world, including Canada, have embarked on this effort. At first, we thought of digitization as a solution to the archive problem. But as technology ages and becomes outdated, we are realizing that digitization is sometimes more fragile than the original material, especially as software and hardware become obsolete. For example, my early digital documentaries (from less than 15 years ago) were built and exhibited in a program called Adobe Flash, which was at the time, available on over 95 per cent of browsers. It was one of the most accessible video and multimedia players of the time. Now, Flash is all but dead. Meanwhile, modern film print, when well preserved, can last longer than 100 years. So will digital works go the way of silent films? (Silent films were made on flammable and very fragile nitrate film and 90 per cent of silent films are now considered lost). UNESCO only recognized moving images as an integral part of world heritage in 1980; it recognized digital heritage in 2001. We are losing some of digital culture faster than we are making it. Some of it is meant to be ephemeral, like Snapchat, but we need to think in deeper ways about how to make it accessible for future generations.

So while the digital shift affords us all sorts of new ways to make, document and share cultures, it also brings new challenges of how to safeguard these new intangible artifacts. We need investment in strategic planning and action on digital and intangible heritage at all levels of government.

In the meantime, don’t forget to print and store those personal pics!

![Rose Lieberman, Rose [Hanford?] Green and Aaron and Sarah Ladovsky in front of United Bakers restaurant, Spadina Ave., Toronto, 1920. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, fonds 83, file 9, item 16.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/SoupsOn_Archival_3505.jpg)