Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

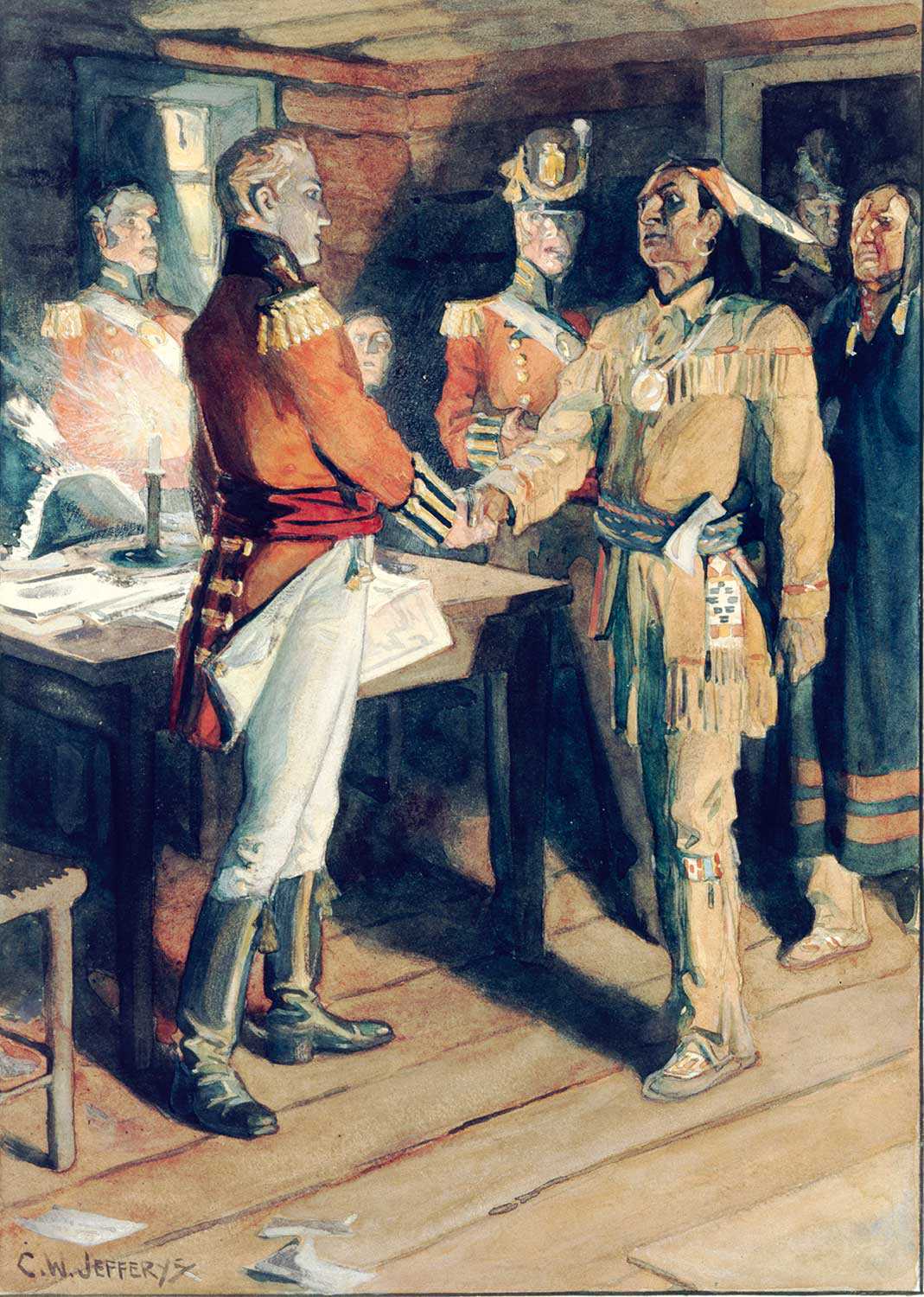

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Fighting power: Ontario soldiers in the making

Military heritage, Community

Published Date: Feb 14, 2014

Photo: Looking considerably more martial is this group of finely turned-out soldiers from Toronto's Queen's Own Rifles, stationed in England before the start of the First World War.

That Canadians are an unmilitary people has become something of a cliché. But a look back at Ontario in the summer of 1914 might leave a different impression.

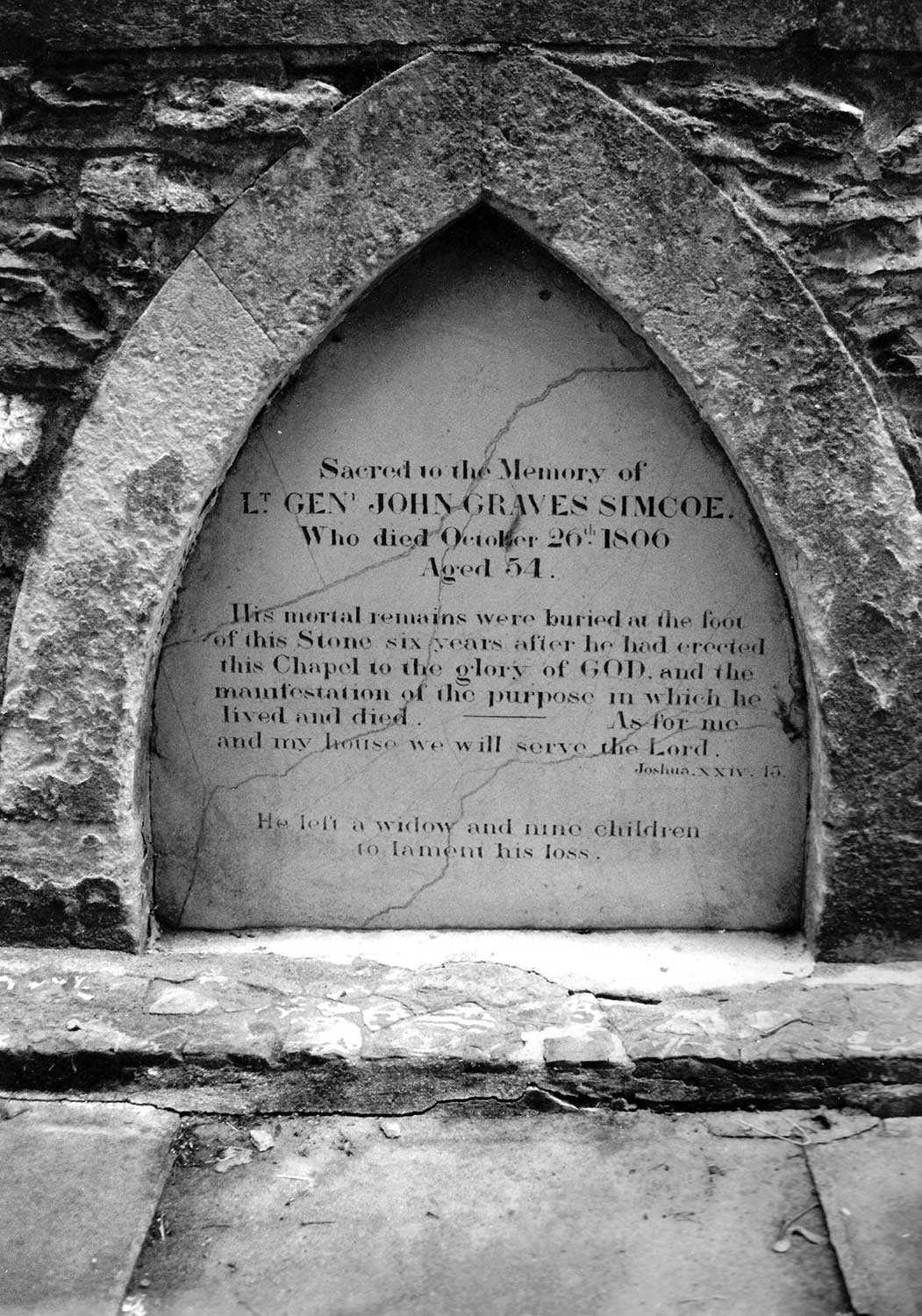

Across the province, units of Canada’s militia were engaged in the annual training ritual. At city armouries (many of them brand new – a product of the federal government’s Edwardian building campaign), part-time soldiers practised drill, musketry, field hygiene and military engineering. The units’ names were impressive – the Queen’s Own Rifles, the Governor-General’s Foot Guards, the Prince of Wales’ Own Regiment – and the men cut fine figures. Their officers were wealthy and influential, and had the resources to ensure that the soldiers always performed well. Some commanding officers even took their units to Britain for summer manoeuvres to sharpen them up and show them off.

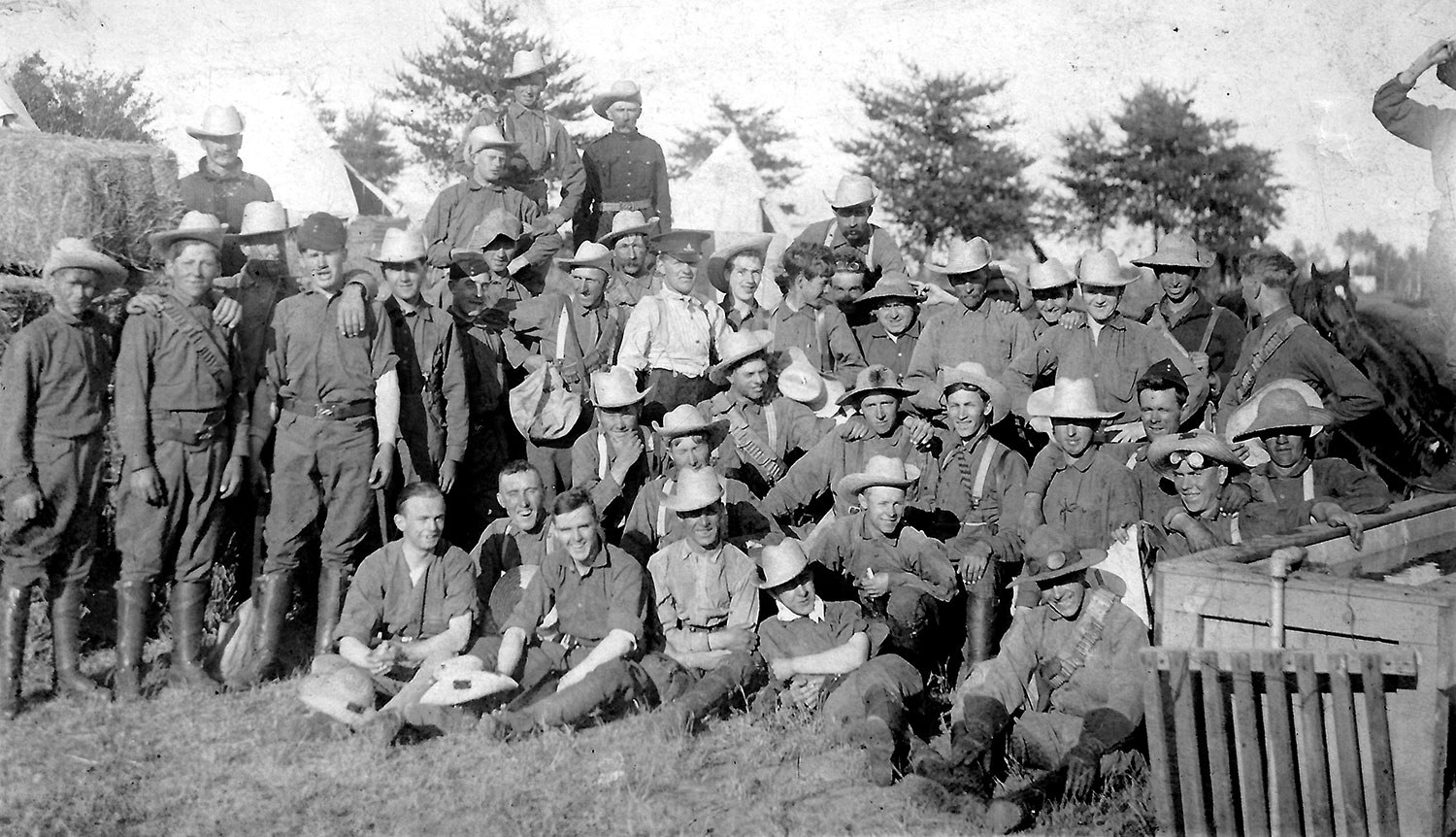

The situation was slightly different outside of big cities. The units’ names sounded just as formidable – the 25th Brant Dragoons, the Simcoe Foresters, the St. Clair Borderers – but contemporary photographs suggest that their summer training camps were more relaxed. The men lounged around in an odd mixture of civilian clothes and military uniforms, with officers sometimes indistinguishable from other ranks. They marched and galloped across the countryside, playing out day-long encounters between opposing armies. The press usually called them “sham battles,” but one eager soldier recognized their true nature and called them “shambles.” For many young men, militia camp was less about training for a future war and more about relaxation, recreation and getting away from the drudgery of the home farm.

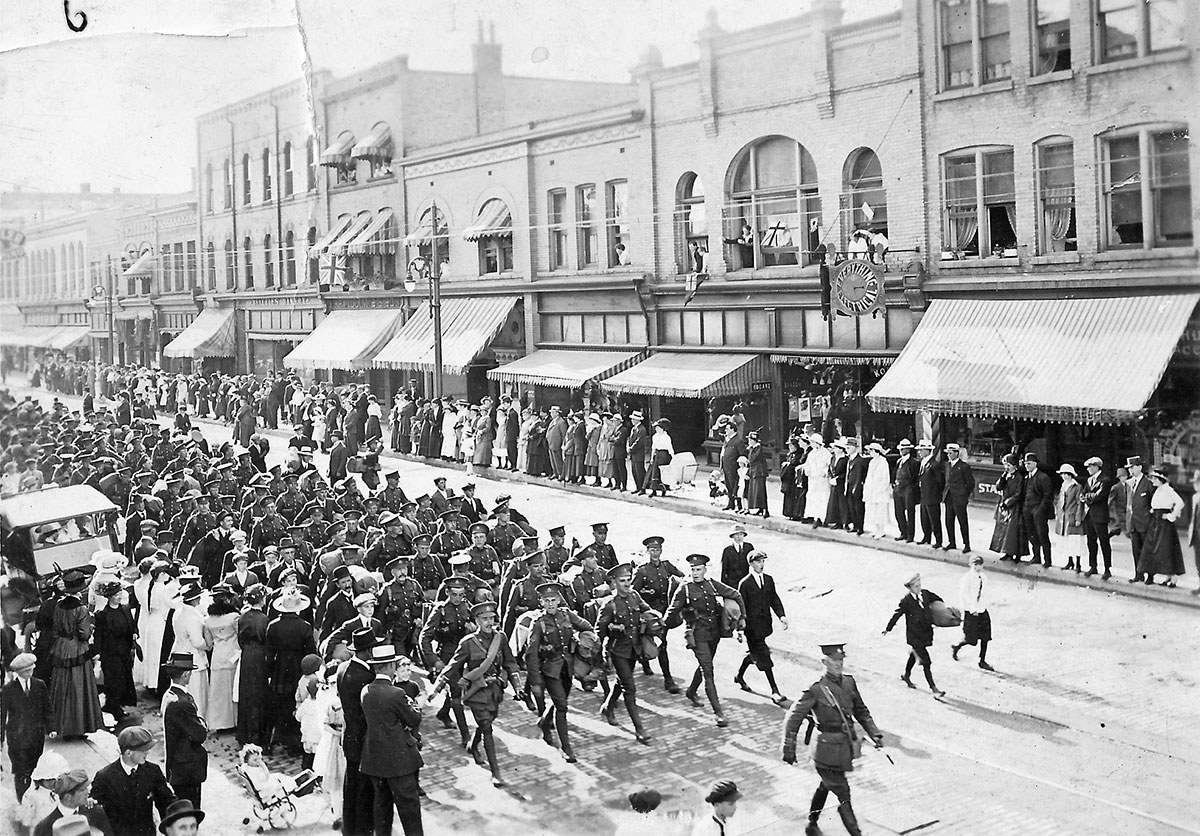

When war broke out at the beginning of August 1914, the cities responded first – or so historians tell us. A few militia units were put on an active footing on July 29 to guard docks, rail junctions and other strategic sites. Then, on the declaration of war a few days later, urban armouries became hives of activity as city workers – many of them British-born and with military experience – answered the call. In the countryside, men were less carried away by patriotic fervour, for their attention was focused on pragmatic rural concerns, such as the coming harvest.

While it should be noted that the majority of early volunteers were, indeed, of British birth, the reality was somewhat different. It was not that men in rural Canada were slower to respond to the call to arms, but that it was more difficult for them to do so. The first call went out to every militia unit across the country, but only those in the cities were told to accept volunteers and send them to the assembly camp at Valcartier, Quebec. It would be two weeks before rural regiments were given the go-ahead to begin sending soldiers. By then, the units of the First Contingent were mostly full. Most rural volunteers had no choice but to wait for the Second Contingent.

Nor were those early volunteers the seasoned soldiers some of them claimed to be. On coming forward for attestation, men were asked if they were serving in the militia or had previous military experience. But their responses should be treated with caution.

A volunteer for the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), before he could join an overseas unit, was often required to join the militia regiment that was doing the recruiting. He would then state that he had militia experience, even if it was only the few minutes it took to complete one form and turn to the second. Nor can claims of previous service be taken at face value, for no proof was required. A volunteer may have said that he had served in Britain’s Territorial Army, safe in the knowledge that no one would try to verify it. Even more difficult were claims of service in foreign armies. Among the volunteers for the Third Battalion, raised in Toronto at the beginning of the war, were men who claimed to have served in the Spanish-American War, the Greek and Russian armies, and the militia of British Guiana. Evaluating such claims – at the time, let alone a century later – was impossible.

Still, by any measure, Ontario’s response to the call for men was impressive. A pre-war mobilization plan had given the province a quota for its contribution to any overseas contingent. In August 1914, Ontario exceeded that quota by approximately 30 per cent.

Ontario’s three divisional areas contributed nearly 10,000 of the First Contingent’s 26,000 officers and men, and even that number was low because hundreds of Ontario enlistments were counted with districts in Manitoba and Quebec.

Furthermore, those numbers did not include many other early volunteers. Ontario was home to thousands of reservists of the British Army (not to mention the French, Italian, Russian and even the German and Austro-Hungarian armies), soldiers who had completed their regular terms of service but could be recalled to their units in the event of hostilities. In the late summer of 1914, Ontario newspapers were full of stories of recent immigrants returning to Britain to rejoin the colours. Ad hoc units, such as the Welland Canal Force and the St Lawrence Patrol, accepted volunteers to protect vital interests. Later, men could join the Railway Service Guard to work on troop trains. Militia regiments also continued to accept volunteers. Late in the war, they would be transferred en masse to the CEF, but in 1914 they did not show up in the usual statistics.

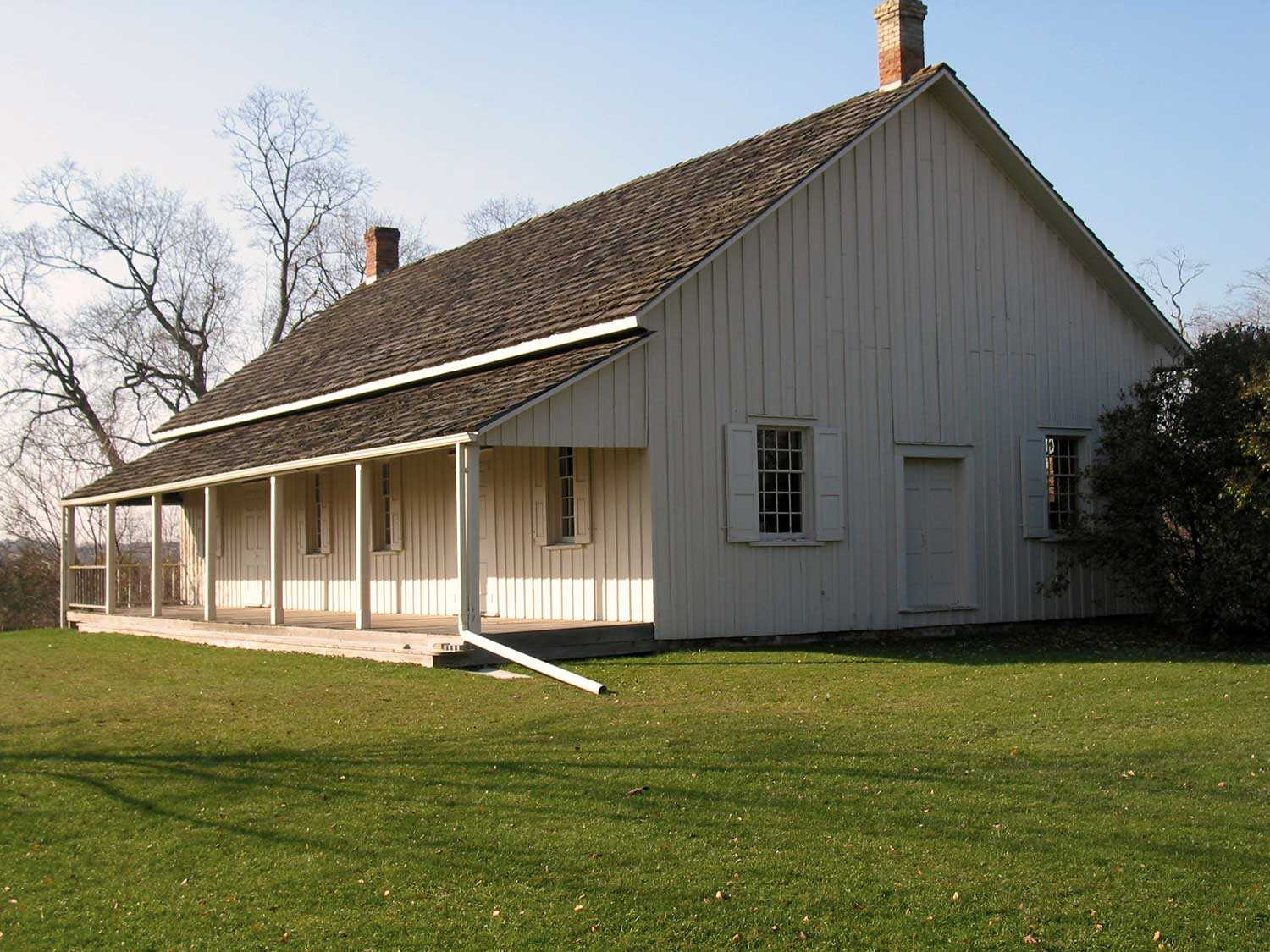

Over the course of a few days in August 1914, Ontario was dramatically changed. The streets may not have looked different. Colourful recruiting posters, Victory Bond advertisements, service flags hanging in parlour windows, black armbands and mourning veils were all things of the future. But the sense that life had changed irrevocably was unmistakable.

At least one Ontario home was already in mourning. Toronto native Stanley Wilson had been serving in Britain’s Royal Navy for more than a decade when war was declared, and his vessel HMS Amphion had been in action from the first day. But, on August 6, the Amphion struck two mines while returning to its base at Harwich and sank within 15 minutes, taking Stanley Wilson and a hundred other sailors with it. Over the next four years, thousands of other Ontario homes would feel the same sting; mourning would become a universal condition. [All images are courtesy of the Ley and Lois Smith Archive of War and Popular Culture, History Department, University of Western Ontario.]

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)