Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Forgotten by her country

Military heritage

Published Date: Feb 17, 2012

Photo: “Open Doors” – Hospitable Pacifism of the Pennsylvania German Mennonites from original artwork by Canadian Artist Nicole Arnt (detail). Copies of this painting are available for purchase at canadianartcards.com.

“My Dearest Jewel.” Such were the words of adoration Lieutenant Maurice Nowlan wrote to his wife on what would become the final night of his life in December 1813. Despite being the eve of battle, his thoughts were only for Agatha. The next morning he was killed during the assault on Fort Niagara.

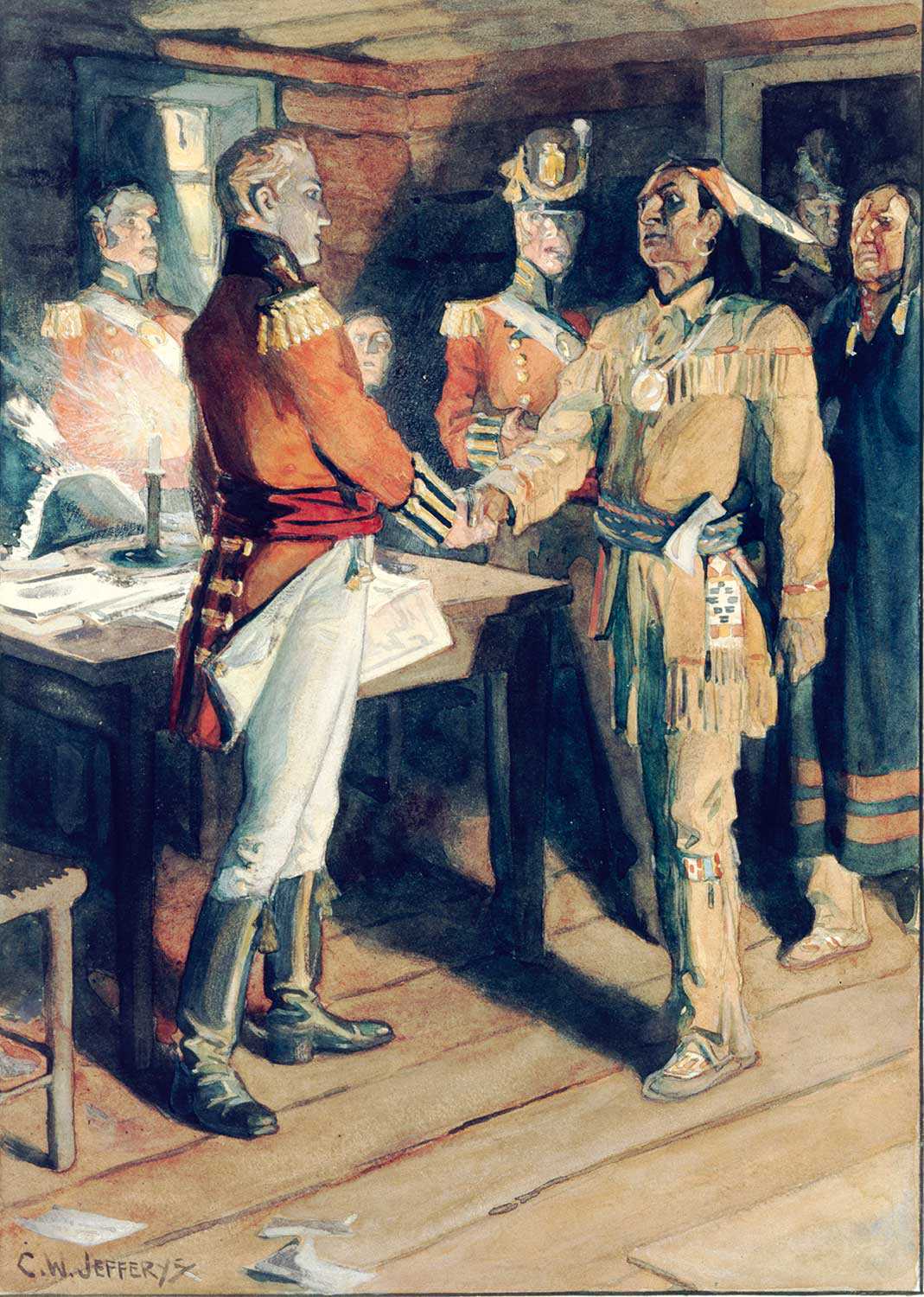

Like many, Agatha and Maurice met and married while he was in service and a war waged. Life continued to be lived, couples married and children were born. Captain William Derenzy of the 41st Regiment stationed at York married Elizabeth Selby in February of 1813; both were present at York during its invasion on April 27, 1813 – both with a part to play in the drama. For Elizabeth, entrusted by General Sheaffe, it was the task of hiding the public treasury funds.

The army attempted to limit the hardships and inconveniences during the war by sending women and children to Lower Canada. They were not always successful, however, in their attempts and exceptions were often made. A District Order from Kingston on June 7, 1813 stated that the women who did not obey an earlier order would not be permitted any “indulgences during their stay in this garrison,” while those who proceeded to Montreal would “be provided with Rations and Lodging.” A few days later, another order was issued requiring all women and children of the army in Upper Canada to be sent to Montreal where lodgings, fuel and rations were provided. Exceptions were allowed for women employed as nurses in the hospitals or who had obtained the special permission of their Commanding Officer. A District General Order from March 1814 sought to limit the number to three women per company “belonging to or proceeding to, the [more prestigious] Right Division.”

War was not the greatest difficulty for women. The greatest difficulty was widowhood. While the Militia and Indian Department established pension systems for the widows of soldiers and officers, native warriors and chiefs during the War of 1812, the Regular Army provided pensions only for commissioned officers and their widows.

If widowed, a soldier’s wife was usually limited in her options: she could remarry into the regiment, or be left destitute, unable to provide food or shelter much less passage home for her children and herself. Military widows could, and did, petition the Commander of the Forces for relief and/or a passage home. In many instances, it is impossible to discover the outcome of these lives and requests as the documents are incomplete. Some documents have “His Excellency’s” decision written on them. No explanations are recorded, merely words such as “complied with for a time limited” written on the document.

Despite the difficult circumstances in which women could find themselves, there were benefits to being a soldier’s wife. For those selected to accompany their husbands, they were not forced to separate from their loved one. While their lives may appear bleak and harsh in many ways, in the reality of the early 19th century, their lives were sometimes better than most. Women and children received regular food rations and, after 1812, military children had access to a mandatory education system, basic as it was – something civilian children in Canada would not share until much later. They also had access to the Army Medical Department, whose surgeons were to provide consultation and treatment for the families. Finally, in some instances, regiments took up collections to assist widows and a compassionate fund donated money to needy widows and orphaned children.

When widowed, it is easy to understand why many women chose to remarry from within their regiments. According to Subaltern Gleig, widows were “perfectly secure of obtaining as many husbands as they may choose.” At Fort York, there were at least two instances of this occurring during the War of 1812 – Mary Lucas in November 1813, and Mary Porter in September 1814. For the widows of commissioned officers, life could be more difficult as they would be constrained by social conventions and unable to seek the security of another marriage as quickly.

And what of Lieutenant Nowlan’s “Dearest Jewel?” Agatha eventually petitioned for assistance, having been left “totally destitute and without the means of support.” In October 1815, nearly two years a widow, she asked to be placed on the pension list and, in accordance with regulations, be paid the additional amount of one year’s pay as her husband had been killed in action. Apparently, the widow of a promising officer who died a hero’s death was forgotten by her country.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)