Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Upper Canada’s first parliament buildings: A place of hopes and dreams

The discovery a decade ago of archaeological remnants of the first and second parliament buildings of Upper Canada in Toronto’s Old Town focused the attention of the city, province and nation on a cornerstone of Canadian history.

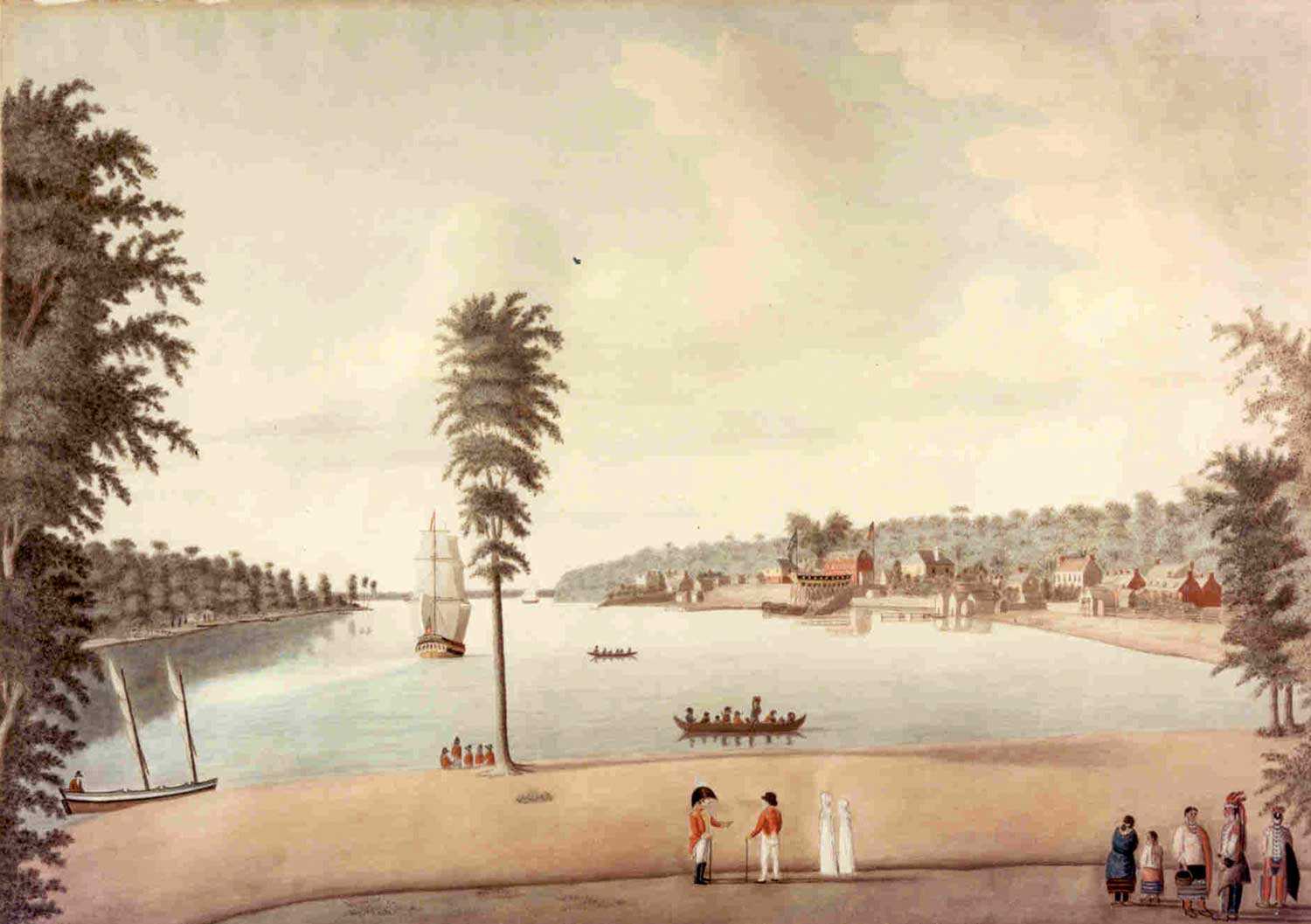

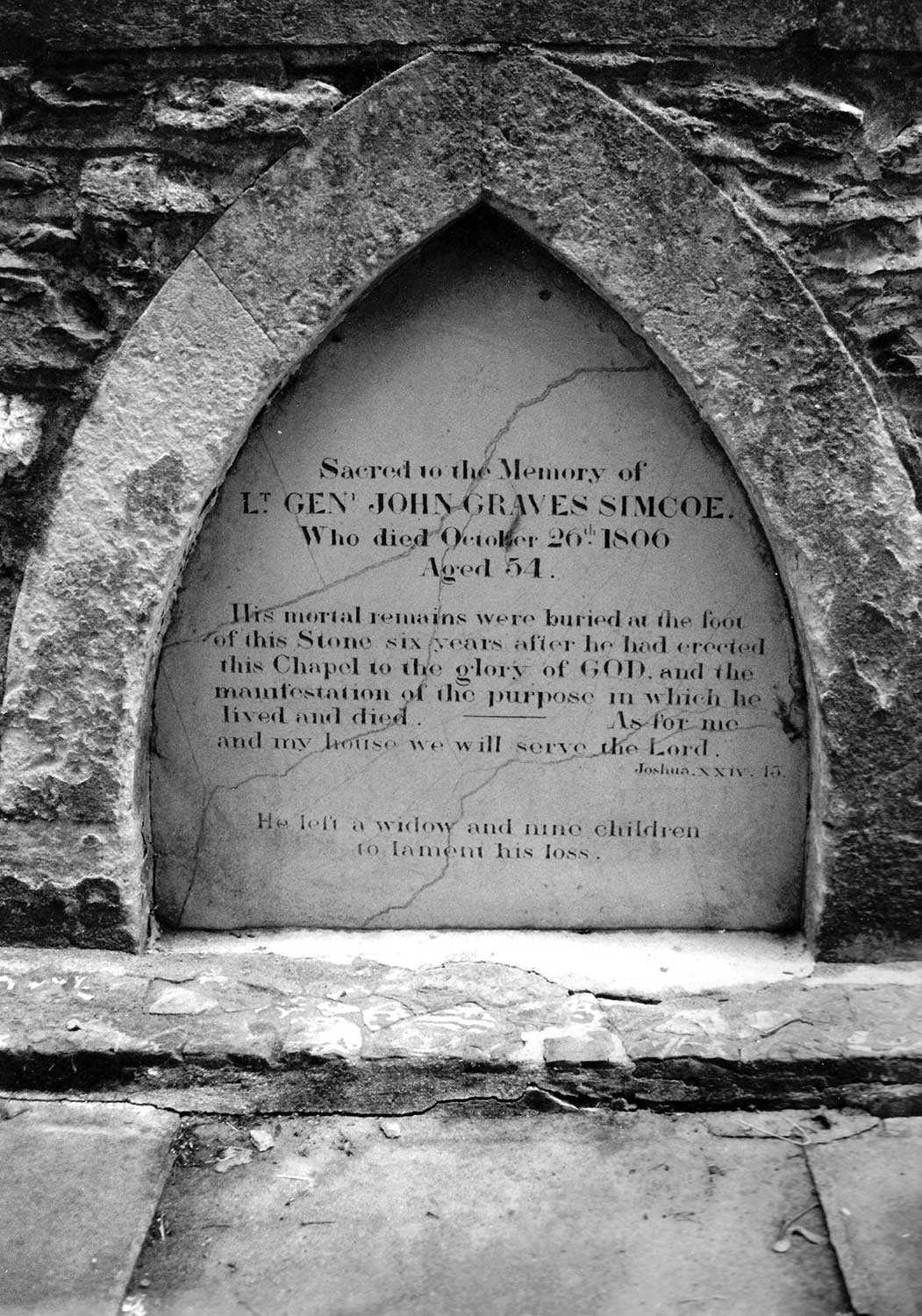

In 1794, Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe moved the capital of the newly established Upper Canada from Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) to York (Toronto). The early development of York was shaped by a plan that included land set aside for the Crown on which the parliament buildings were constructed. The first buildings, erected in 1797, consisted of two brick structures measuring 40 feet by 24 feet and situated 75 feet apart. They were likely one and a half storeys high, each with a small viewing gallery. Immediately east of the brick buildings were two 30-foot-long frame structures used for committee rooms.

The parliament buildings were used for many government and public functions beyond the sitting of the legislature (which was typically for only two months of the year). These uses included the Court of Appeal, Court of King’s Bench and District Court; another notable occupant was the Anglican Church. The site also had a military presence in the form of a blockhouse, built in 1799 on a bluff less than 10 metres from the shore of Lake Ontario.

On April 27, 1813, the United States army and navy mounted a successful attack on York, occupying York for six days – looting homes, confiscating or destroying supplies, and burning various public facilities, including Government House at Fort York, the parliament buildings and the adjacent blockhouse. Among the items taken from the parliament buildings was the Assembly’s ceremonial mace (the symbol of the Assembly’s power). President Franklin D. Roosevelt returned the mace to the Ontario government in 1934.

Early bricks (note the burnt bottom one). While it is surprising and fortuitous that archaeological remains of the parliament buildings have survived later institutional and industrial development on the block, recent work on the site has, to date, failed to uncover any additional remains of the buildings, which makes the original find all the more remarkable.

Soon after the 1813 American invasion, and while Fort York was being rebuilt, the parliament buildings, whose walls had survived the fire, were hastily repaired and were used to billet 200-300 British troops. By early 1816, the military reconstruction of the garrison was completed and the troops returned to Fort York. In June 1818, acting on the legislature’s advice, instructions were given to commission plans for new government buildings. The first session in the new buildings opened in December 1820 but they, too, were destroyed by fire on December 30, 1824. The land was vacant until the late 1830s, after which time it was occupied by the District Gaol and then the Consumers’ Gas Company complex. The property was redeveloped in the 1960s to include a number of light commercial enterprises.

In 2000, archaeological investigations focussed on the Consumers’ Gas courtyard as it was thought to represent the best opportunity for the survival of parliamentary building remnants. In one of the excavation trenches, they discovered the dry-laid stone footing of the east wall of the south parliament building. Extending into this footing were several linear charcoal stains that had clear and distinct outlines. They were the charred remains of partial lengths of floorboards and floor sleepers or joists that had burned in place, resulting in the creation of the ghostly images of the boards. The earliest known fire on this block was the one set by Americans during the War of 1812. Not surprisingly, similar evidence for burned floor sleepers and joists was documented during excavations at Fort York on buildings that were also set alight by the Americans.

These remains are a testament to a place of hopes and dreams in a new land. The parliament buildings were among the first brick structures in the town and were referred to as Palaces – the Palaces of Government (at one time, Front Street was called Palace Street). These were buildings where decisions were made that helped to shape the province and the nation. We celebrate the work of the Ontario Heritage Trust to interpret this place and to tell the important and fascinating stories with which it is associated. Charred floor joists extending into the stone footing. Mixed in with the floor complex were numerous fragments of thin, early-19th-century red brick, some of which were burnt. Other artifacts recovered from within the floor complex included mainly late-18th- and early-19th-century ceramics, some of which were also charred.

Note: The ASI worked with the Trust to complete an archaeological assessment of the site of the first parliament buildings in 2000.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)