Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

The heritage of Ontario’s forts

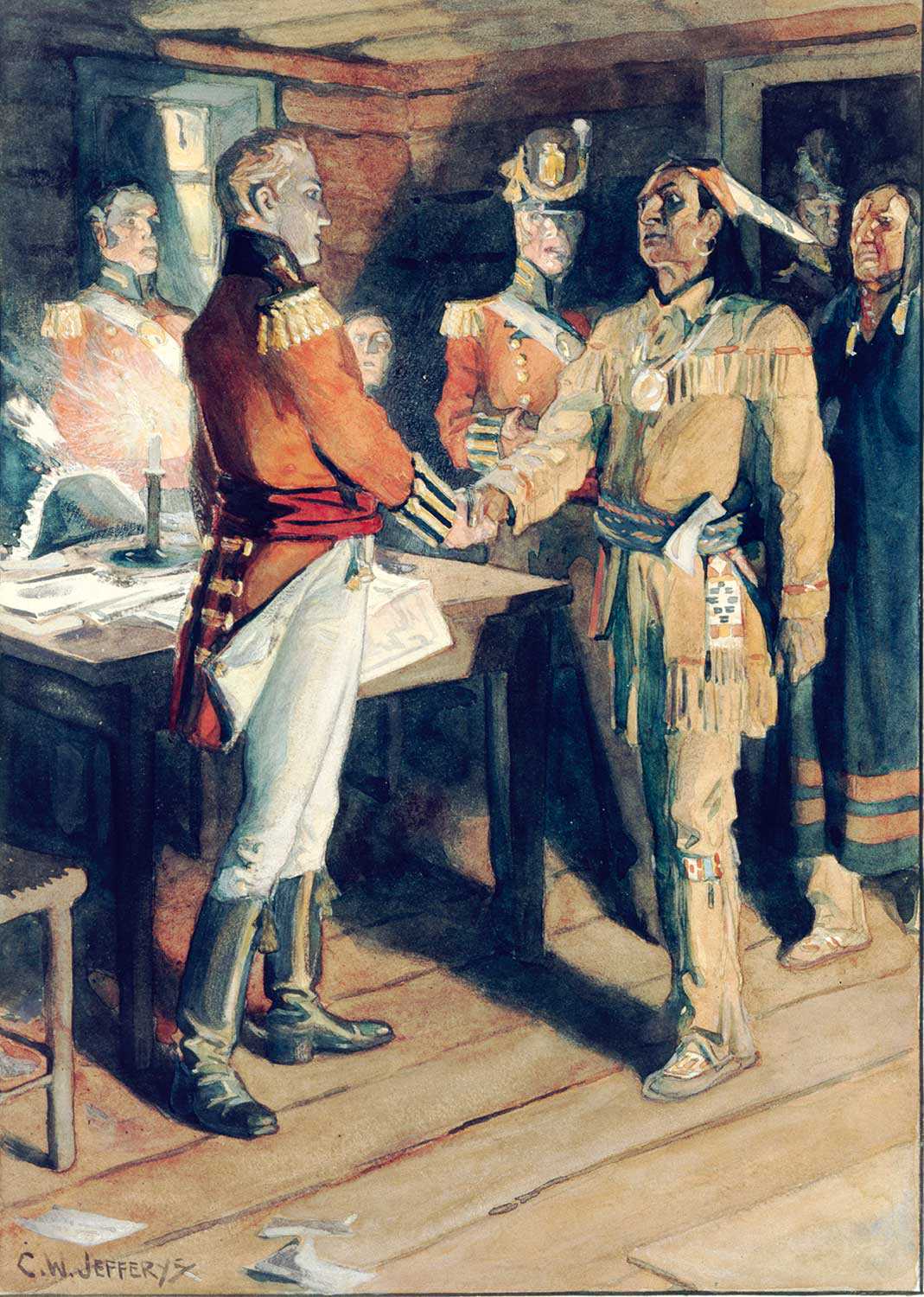

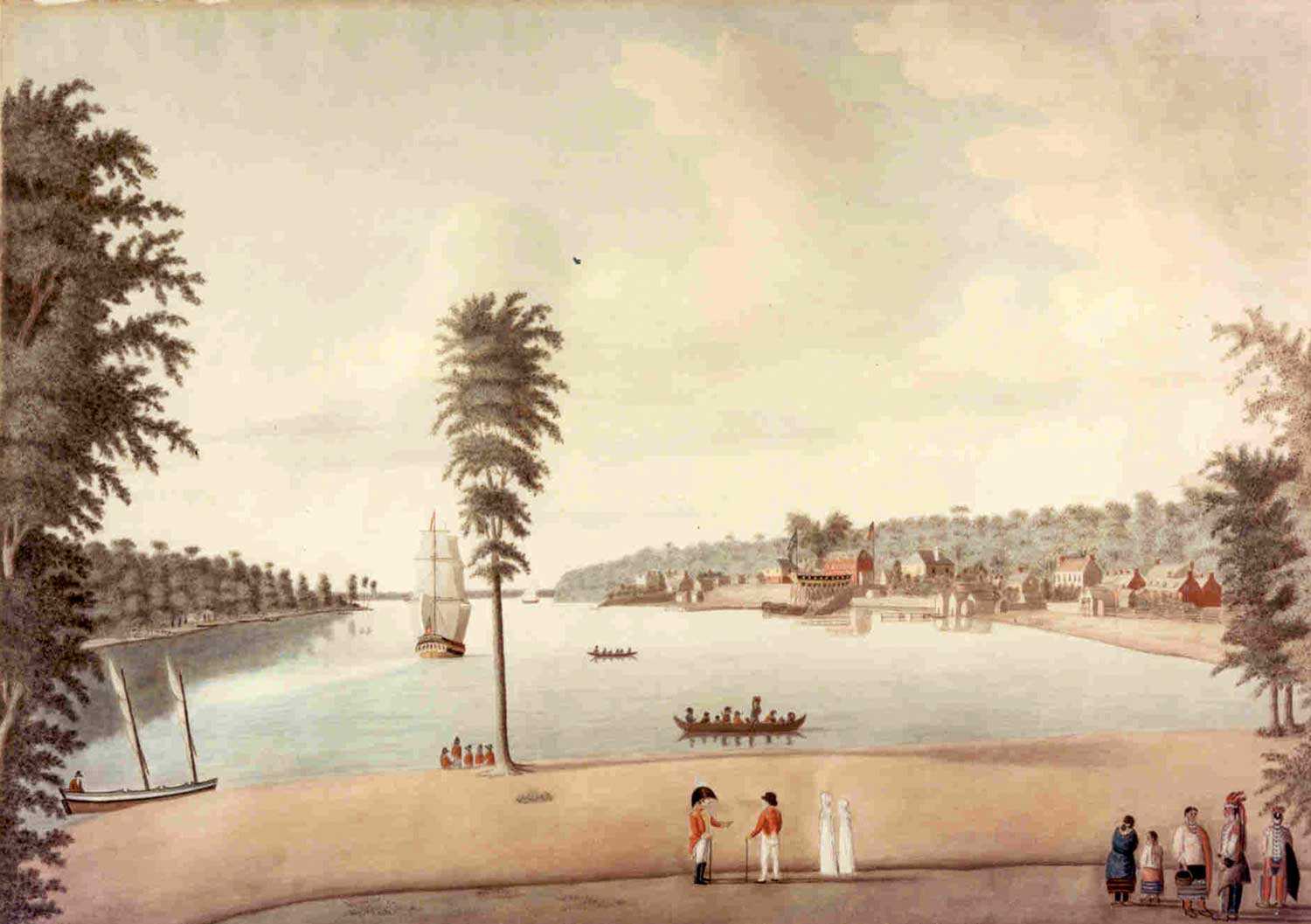

The War of 1812 marked the beginning of a fascinating history for many of Ontario’s forts.

To protect strategic points throughout Upper Canada, the British poured significant resources into defending the colony from invading Americans. After the War of 1812, many of these fortifications fell into disrepair. The outbreak of rebellion in 1837, however, and subsequent border raids gave renewed life to these sites. Once again, the British poured resources into refurbishing many forts. Then, following Confederation, responsibility for these sites was transferred to the new Canadian government.

While some properties continued to serve military purposes, others found new uses. The gradual disappearance of some forts caught the attention of heritage-minded groups. In 1889, the Lundy’s Lane Historical Society fought to erect a marker on the historic battlefield. Eventually, however, heritage groups shifted from simply marking sites to actively promoting their preservation. This was the case in Niagara. In 1905, the Niagara Historical Society successfully campaigned to have the government commit to preserving historic Fort George.

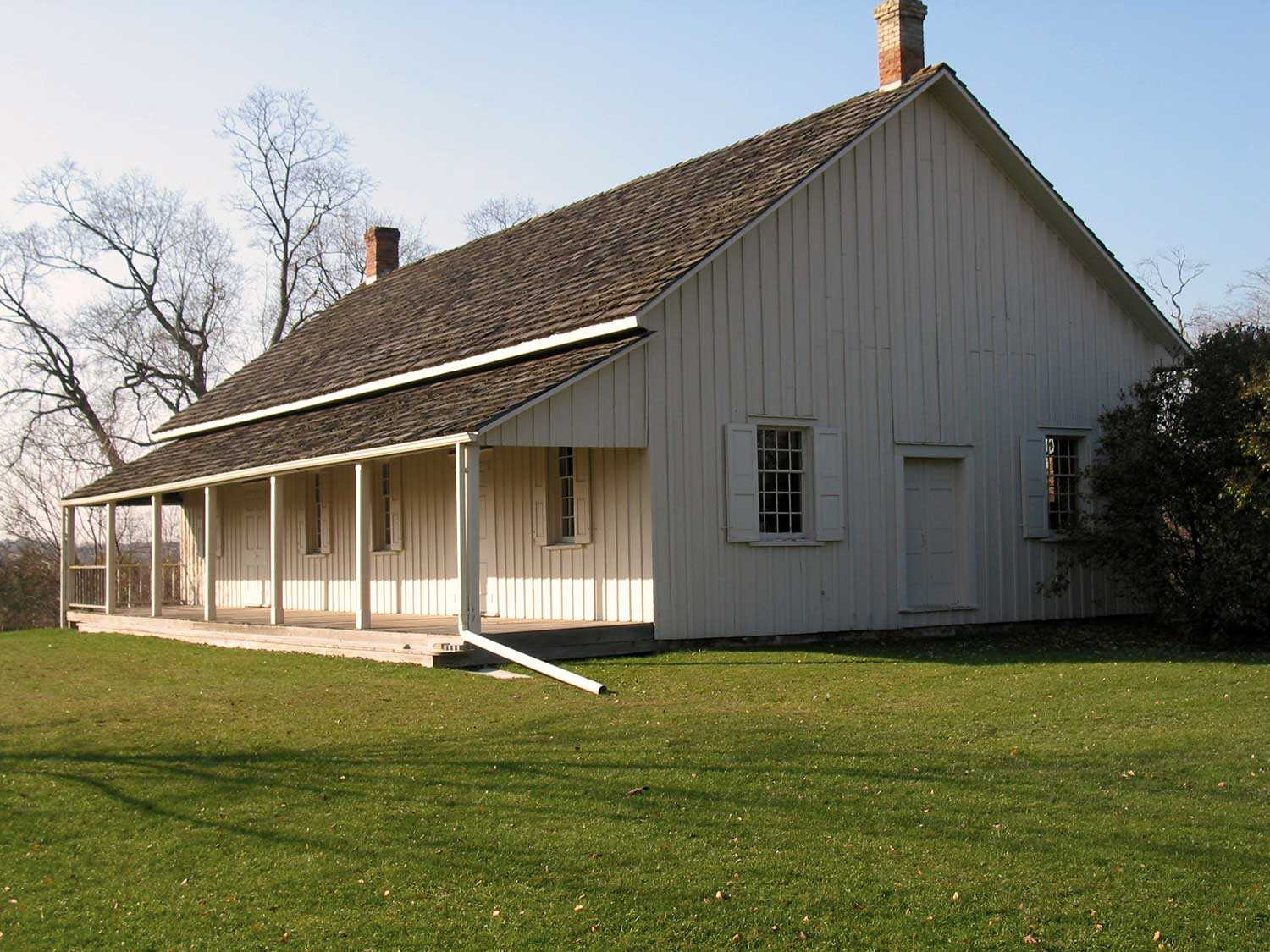

An even more intense battle raged over the threat to Toronto’s Fort York. In 1903, the federal government sold the military reserve to the city; the city agreed to preserve the grounds and restore the site to its 1816 configuration. Contrary to the agreement, however, city officials planned for a streetcar line to run directly through the fort, demolishing several buildings along the route. Under the leadership of the Ontario Historical Society, Fort York preservationists waged a vigorous campaign to thwart these efforts.

The residents of Amherstburg were even more ambitious in their efforts to protect the remains of Fort Malden. In 1904, they petitioned the federal government to acquire the property and convert it into a national historical park. Although interested, the government had no mechanism to create such parks. The establishment of the Dominion Parks Branch in 1911 was more concerned with the management of parks and forests. But interest for a national heritage program gained momentum with the 1919 creation of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board.

The early work of this Board coincided with the disposal of surplus military property, resulting directly in the acquisition of Prescott’s Fort Wellington in 1924 as a historic park. With a precedent set, the heritage group in Amherstburg renewed efforts to have Fort Malden acquired.

During the Great Depression, all governments struggled to stimulate economic growth and combat unemployment. Ontario embarked on an ambitious program to reconstruct the forts at Kingston and Niagara. These make-work projects created employment and enhanced the potential for attracting tourists from the United States. Ironically, these forts – originally built to repel American forces – were now being restored to attract American tourists.

Many compromises on historical authenticity were made in reconstructing the buildings and grounds of our forts; the philosophy of commemoration at the time emphasized accommodating the needs of the visiting public over the accuracy of reconstruction. This philosophy changed by the 1970s as the Parks Service became Parks Canada and a growing staff of historians, archaeologists and conservators supported the development of a strong national program of heritage commemoration.

As Ontario prepares to commemorate the bicentennial of the War of 1812, this rich legacy of historic forts and parks will provide a memorable experience and appreciation of this critical period in our province’s history.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)