Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Keeping the peace: Quakers and the War of 1812 in Upper Canada

Despite the fact that the War of 1812 came literally to the doorsteps of members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), only a handful had any voluntary involvement in the conflict. This should not suggest that they were not affected by the war. On the contrary, Quakers suffered deeply for their pacifism.

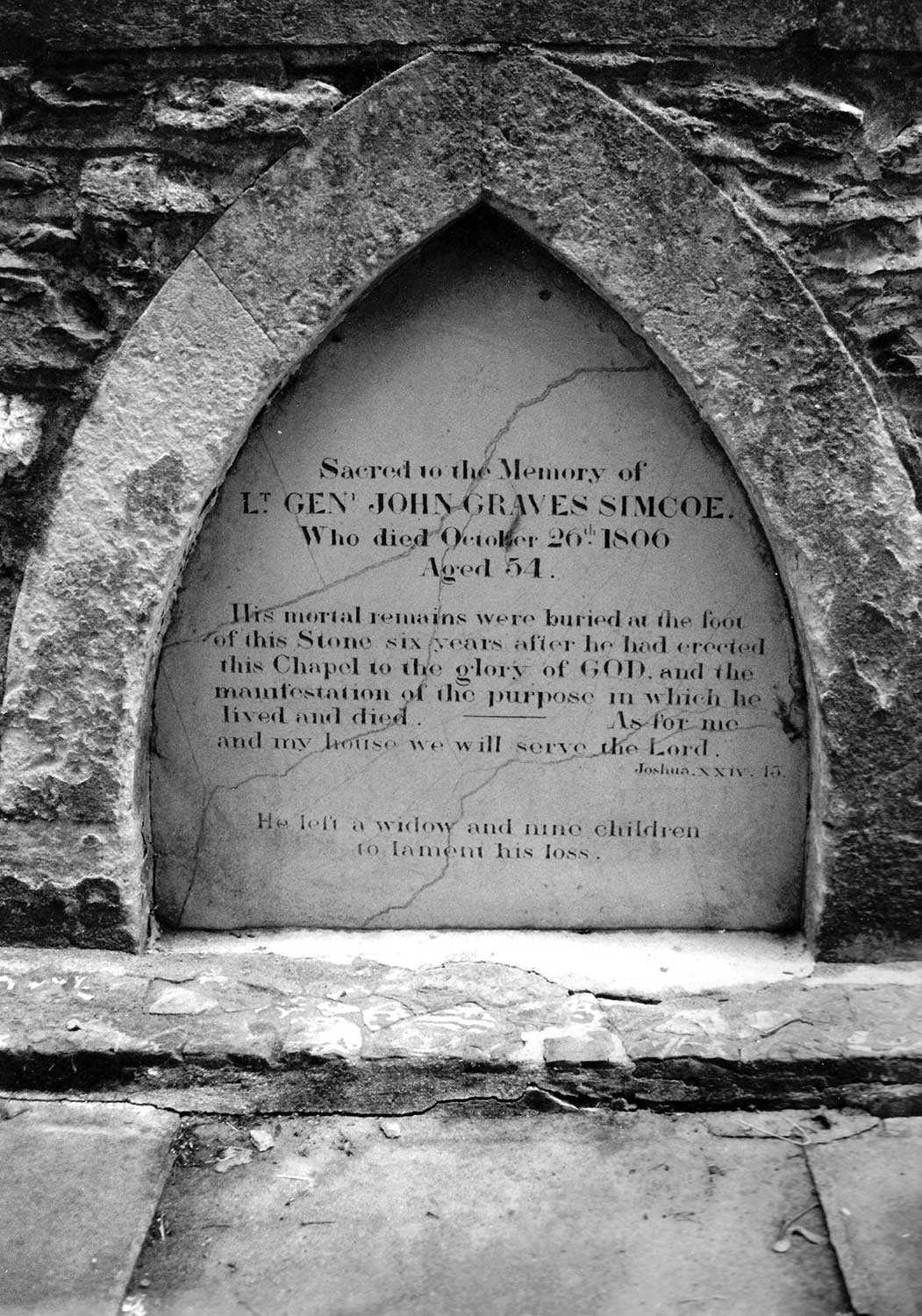

Friends’ pacifist position was well-known to the Upper Canadian government. In 1792, Lieutenant Governor Simcoe encouraged Quaker settlement by promising some exemption from militia duties. In 1806, one Quaker meeting presented an official address to Lieutenant Governor Gore, assuring him of their commitment to the “welfare and prosperity of the province,” while reminding him that “we cannot for conscience sake join with many of our fellow mortals . . . in taking up the sword to shed human blood.”

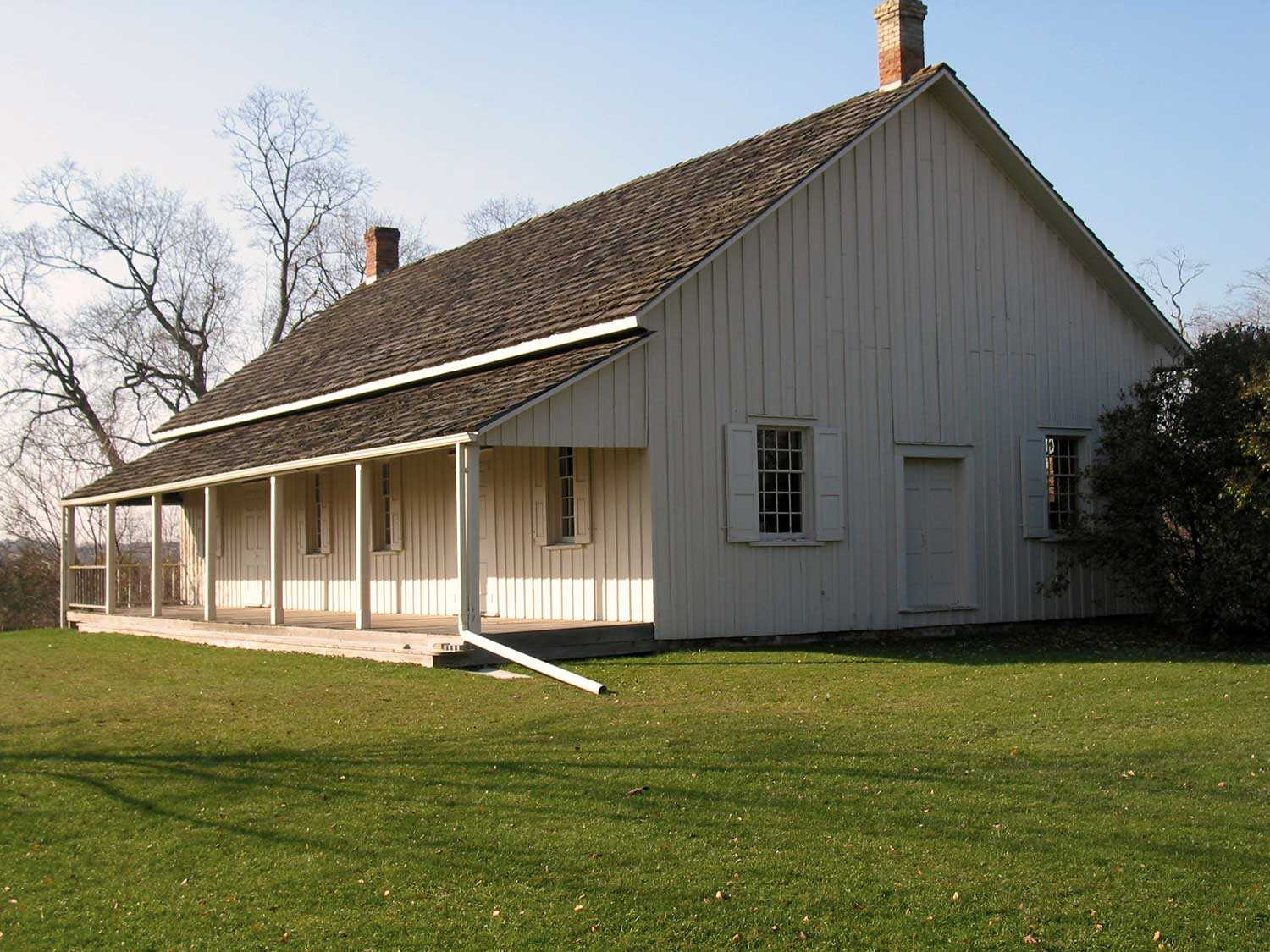

Despite government concessions for religious testimonies, the Militia Acts of 1793 and 1794 permitted exemption from military service only on the condition that fines were paid in lieu of service. Quakers refused to pay these fines on the grounds that this action supported military activity. Those who did pay fines or engaged a substitute for their service faced discipline and possible disownment. Quakers also prohibited participating in militia roll call or military exercises, even if no fighting took place. When they refused to pay military fines, the colonial government responded by seizing their property. In the years between 1806 and 1812, Quakers paid dearly in property and goods; a number of them paid the penalty of a month in prison. While Quakers throughout the province suffered on account of their principles, Yonge Street Friends were affected most severely, no doubt the result of their proximity to the capital of York.

Most Quakers stood by their pacifist beliefs when war erupted in 1812 and very few joined the conflict voluntarily. If their horses or other goods were appropriated, Friends were expected to bear their loss willingly. Because many Quaker farmers refused government war bills as payment for grain or for billeting soldiers, they lost revenue as well as giving up property.

The peace testimony at this time was really an anti-war testimony. Any and all connections to war or war activity were forbidden. With very few exceptions, Quakers abided by these restrictions. Their settlements were still relatively new and usually set apart from other colonists. The Yonge Street settlement had just recovered from an epidemic that ravaged the community in 1809; a second unknown epidemic swept through the settlement in 1812-13. And, in 1812, David Willson led a group that broke away from the Yonge Street Friends to form the Children of Peace. The seeds of division among Quakers were sown.

The war had a devastating impact on Quakers in Upper Canada, but it was more than war that proved to be so devastating to Upper Canadian Quakers during this period. War posed not only an external threat, but it also led to internal division and disruption among the Quakers.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)