Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

From Stratford to Shaw: Transforming smalltown Ontario

"Stratford has grown up around the Festival, maintaining its historical and natural beauty, while also encouraging small businesses that cater to both the local and tourist populations. Shops, restaurants, small inns and B&Bs abound. Because of the Festival, Stratford now boasts an internationally acclaimed chef’s school, a public art gallery, a music festival and many other cultural activities, existing in a remarkable symbiotic relationship."

Anita Gaffney, Executive Director, Stratford Festival

It’s hard to imagine either Stratford or Niagara-on-the-Lake being where they are today without their world-renowned theatre festivals. But, before these festivals opened their doors, both small towns had other identities entirely. By adapting to change, these communities avoided becoming outmoded or marginalized. Elements of each town’s unique history, geography and architectural character helped make them ideal locations for their respective festivals.

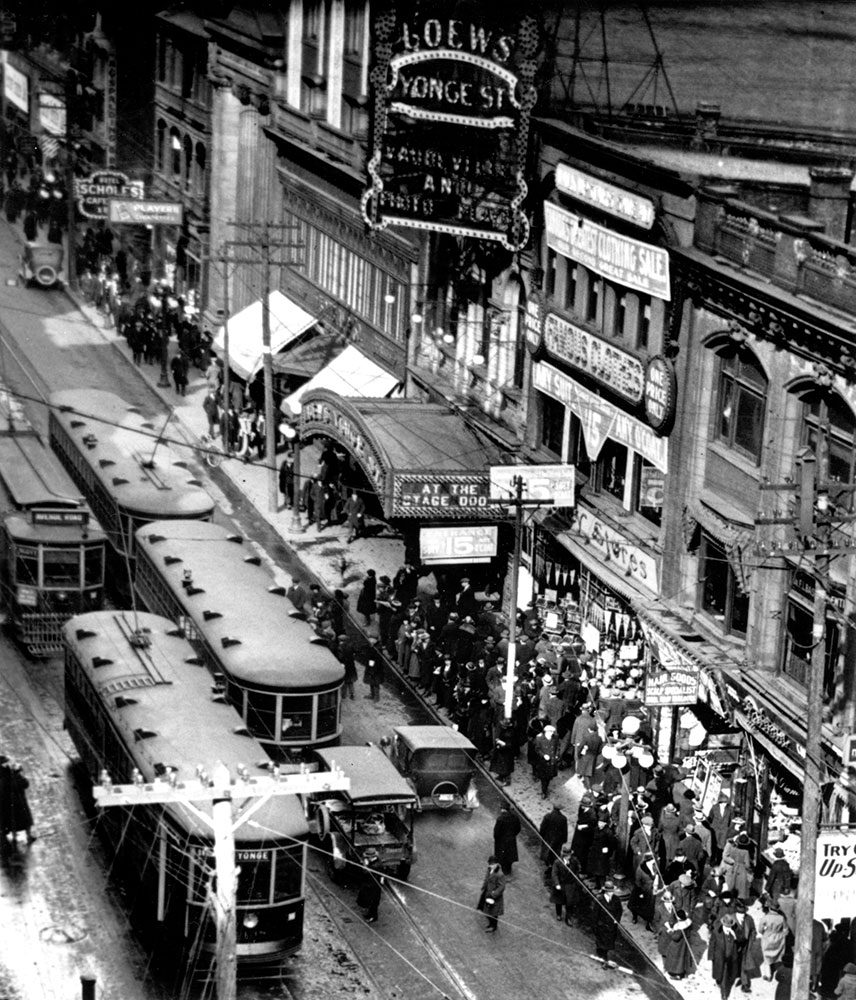

Stratford, incorporated as a city in 1885, had already enjoyed a boom time. With a burgeoning manufacturing industry aided by the Canadian Pacific Railway that ran through and dominated the town, Stratford quickly became a thriving commercial centre along the Avon River. So successful was the railway development that, in the early 20th century, a number of local advocates – particularly local businessman R. Thomas Orr – had to fight to prevent the scenic Avon waterfront from being developed by the railway. But the Great Depression devastated the community’s economy and the city’s industrial base slowly declined.

But people did not give up on Stratford. Orr was instrumental in developing the extensive parks system that still runs along the river. Orr also developed links between his city and the birthplace of William Shakespeare.

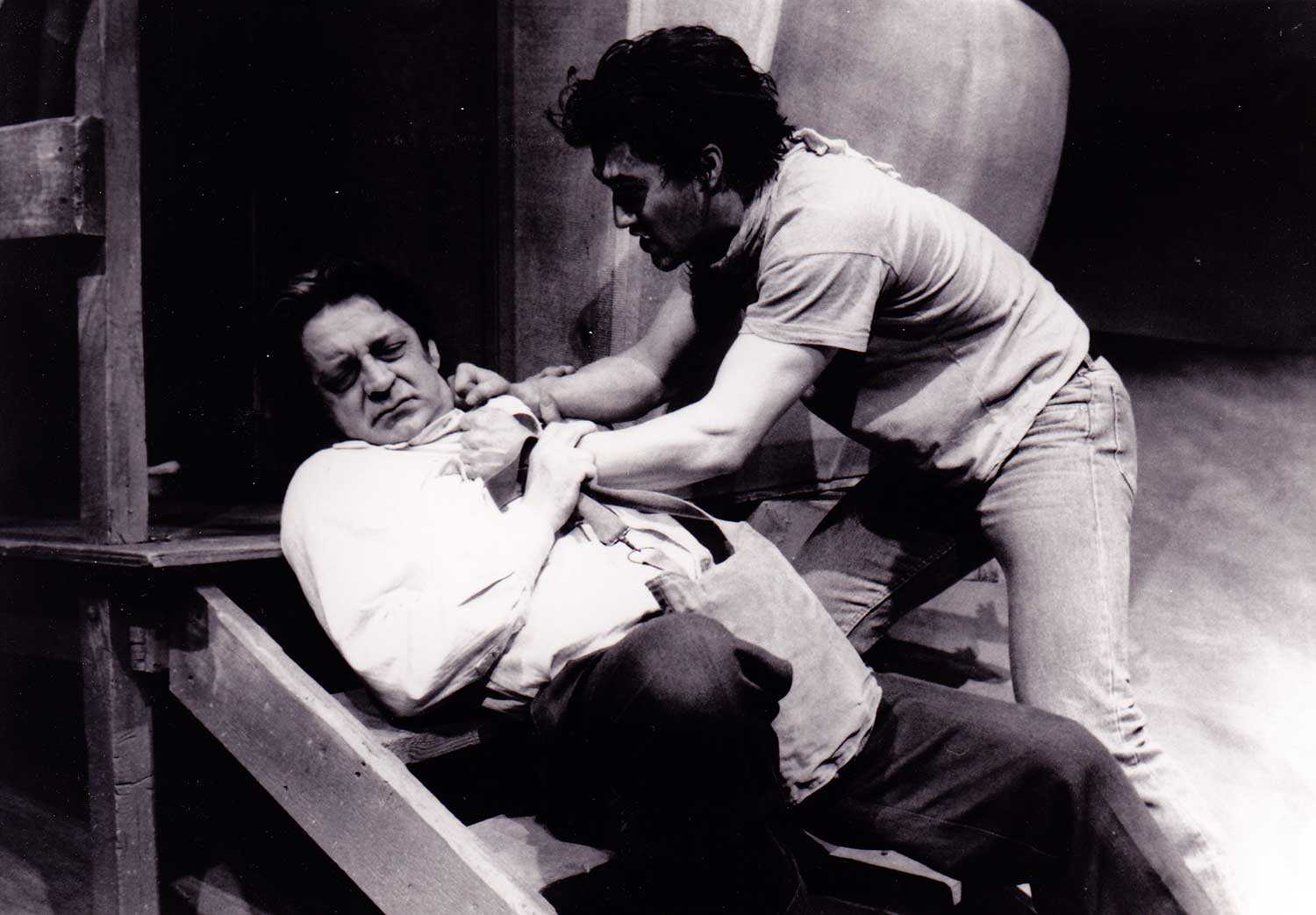

Tom Patterson, inspired by the beauty of his hometown, became obsessed with establishing a theatre festival that would put Stratford on the map. In 1952, Patterson established the committee that would become the Festival’s board of directors. Later that year, with assistance from Canadian director Dora Mavor Moore, an introduction was made between Patterson and British director Tyrone Guthrie (who became the Festival’s first Artistic Director). Guthrie was intrigued by the opportunity to launch a Shakespearean festival.

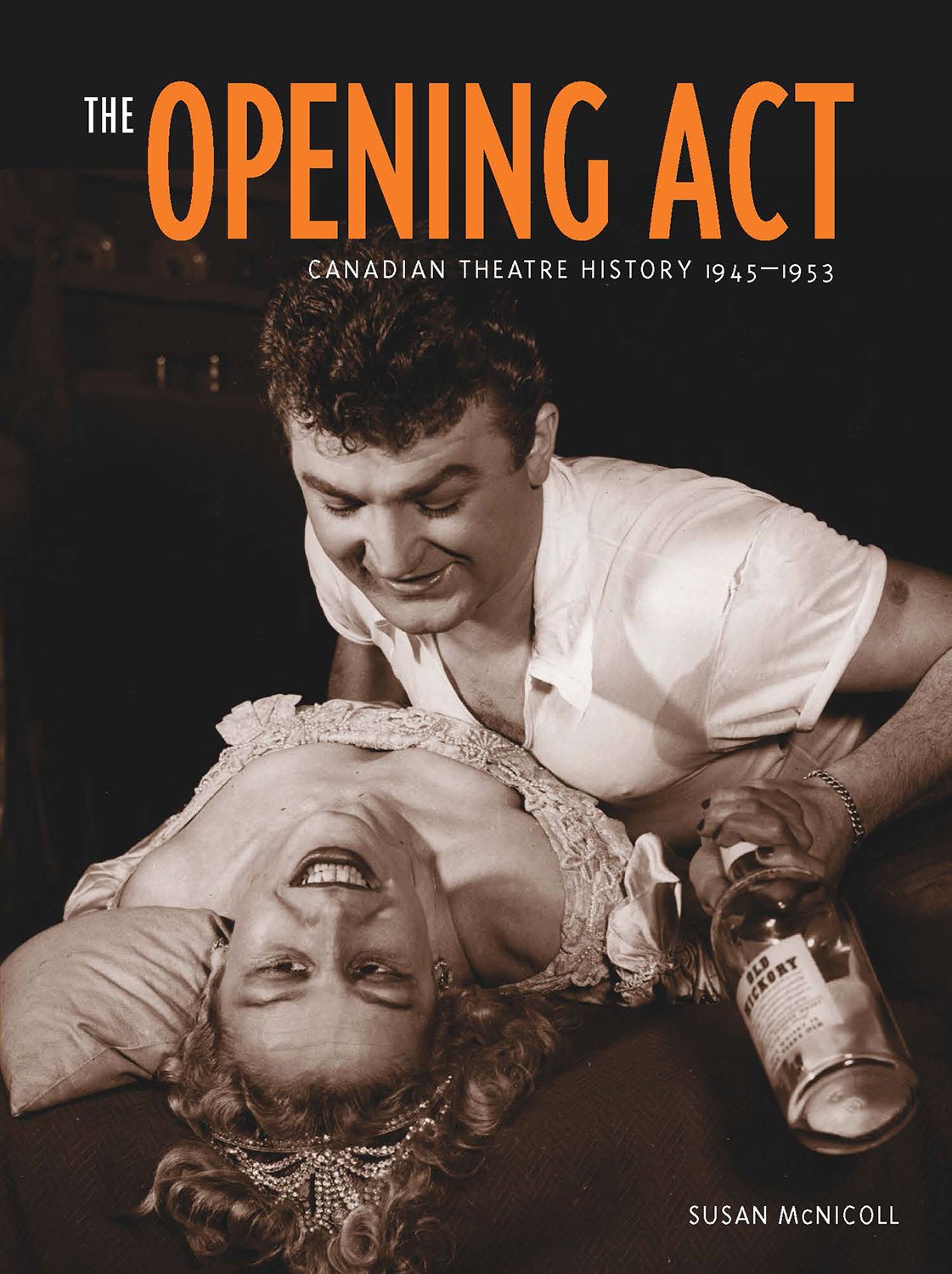

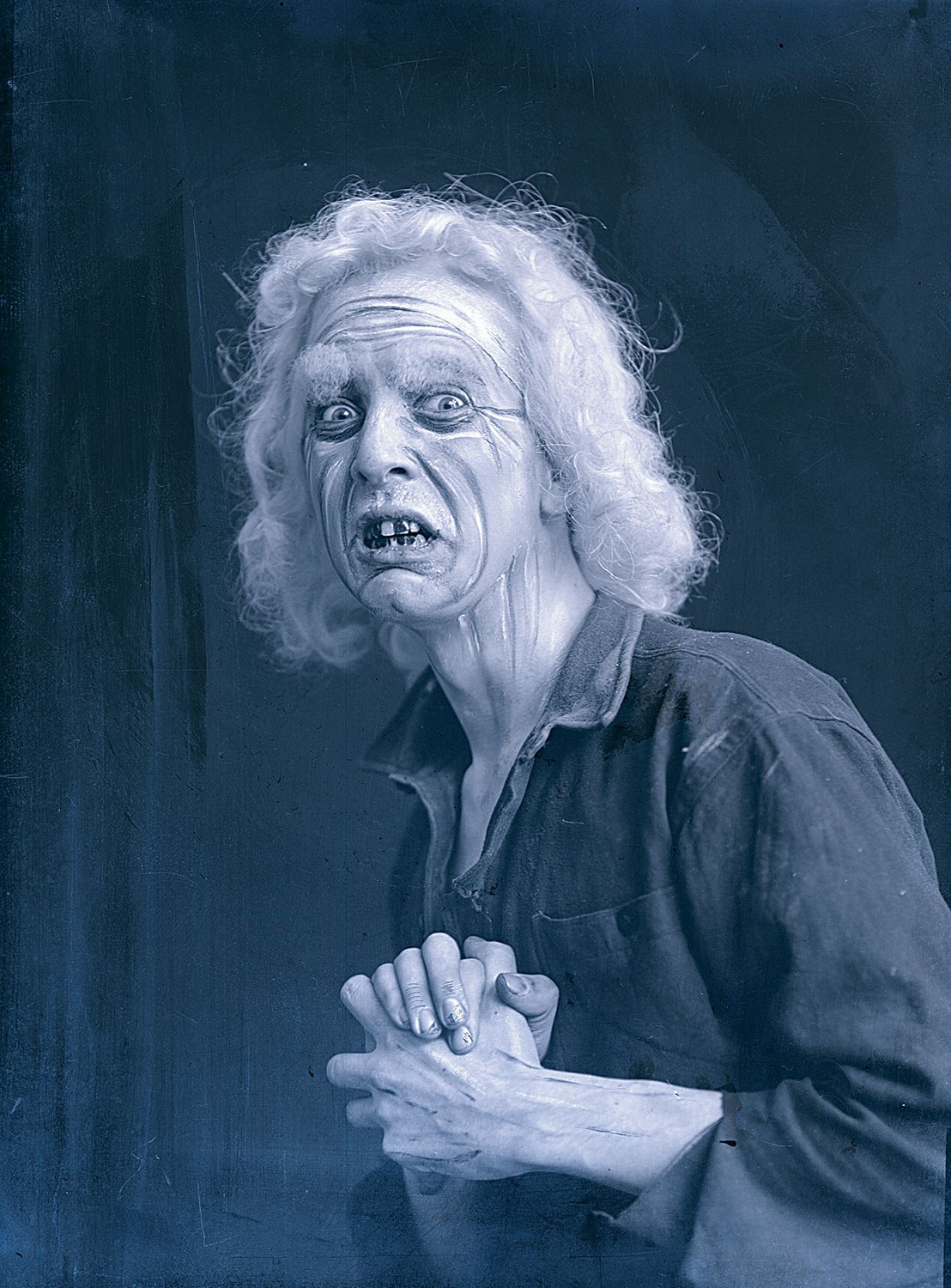

The Stratford community rallied around Patterson and the Festival. Local citizens became volunteers on the gates and at the box office, and even opened their homes to provide accommodations for the actors and theatre patrons. The Stratford Festival opened to rave reviews on July 13, 1953 with a production of Richard III.

Today, the Stratford Festival remains the city’s largest employer, generating approximately $140 million in economic activity annually. The community still rallies around the internationally acclaimed festival and enjoys significant economic spin-off – with restaurants, bed and breakfasts, and local shops all benefiting from the hundreds of thousands of tourists flocking to Stratford each year.

Stratford has become synonymous with the arts in Canada and is a leading contributor to the growth of the city’s creative economy. This vitality has also encouraged the development of a progressive business park and has attracted the University of Waterloo to open a campus in Stratford that specializes in digital media and technology.

Moreover, Stratford’s heritage conservation renaissance over the last 25 years has been fuelled by the success of the Festival. In recent years, a large number of historical buildings in Stratford have been adapted to house services and businesses that directly and indirectly support the Festival. Additionally, a heritage conservation district protects the downtown.

The Shaw Festival’s Edwardian Royal George Theatre on Queen Street in Niagara-on-the-Lake. (Photo: Andrée Lanthier)

Niagara-on-the-Lake has a similar history that places it firmly on the map as far back as the arrival of John Graves Simcoe and the American Revolutionary War. Following the War of 1812, when much of the town was destroyed, Niagara-on-the-Lake slowly regained its economic health. But its preferred geographic location was further eclipsed in the 1830s when the Welland Canal was built.

Despite these setbacks, the town continued to expand throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Tourism blossomed during the 1870s when hotels started to appear. Leisure activities flourished and some summer tourists eventually became year-round residents.

By the mid-20th century, however, Niagara-on-the-Lake was seen as somewhat adrift. Visitors and residents alike referred to it as quiet and unhurried or just plain dull. While it could still boast beautiful historical buildings, some of them were falling into disrepair. With steamers and trains now bypassing the town, sleepy little Niagara-on-the-Lake was slowly disappearing.

Then, in 1962, the town’s outlook changed. Brian Doherty, a Toronto lawyer who had moved his practice to Niagara-on-the-Lake, brought together a small group of people to generate ideas to revitalize the town. The conversation almost immediately turned to theatre – Doherty’s passion. He had not only written for the stage (and enjoyed modest success on Broadway), but he had also produced theatrical productions and was on first-name terms with several leading London and New York actors. When the discussion turned to their preferred focus, George Bernard Shaw’s name rose almost immediately to the top of the list.

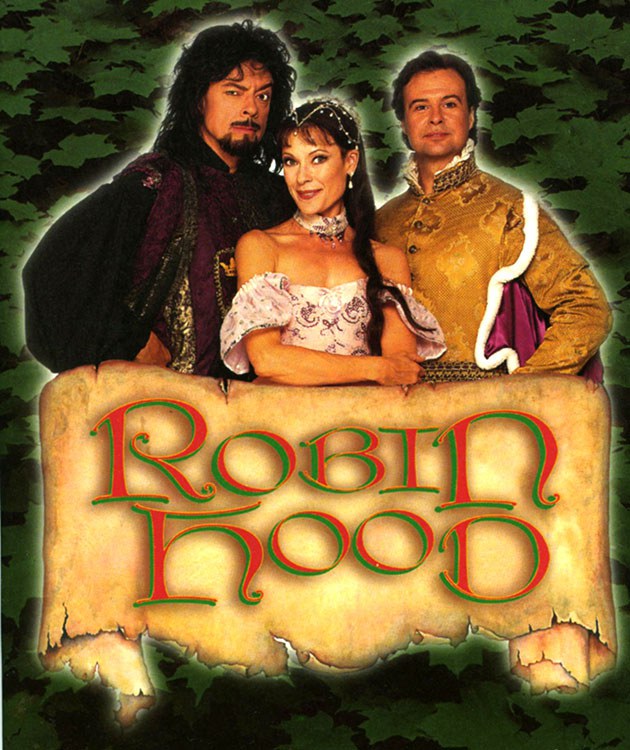

With a local organizing committee, the backing of an enthusiastic town, an obliging council and with actors and a director secured, the “Salute to Shaw” – as the first season was known – opened on June 29, 1962 with a production of Don Juan in Hell, followed by Candida. The Shaw Festival was born.

The historical setting and natural beauty of the town has played a large role in how The Shaw has marketed itself. The town of Niagara-on-the-Lake is steeped in tradition, with many families able to trace back their roots to the War of 1812. Careful consideration of local traditions and sensitivities of those living in the town for many years has impacted how The Shaw has done business, how we communicate to our local audience and how we partner with local businesses. (Odette Yazbeck, Director of Public Relations, Shaw Festival)

In the years following the Festival’s launch, interest in architectural preservation grew in the community. The town became known as a centre for conservation expertise and many of its landmarks were restored and rehabilitated in the 1970s. In 1986, the town designated its downtown core a heritage conservation district. In 2003, it became a National Historic District – another example of how the arts and culture served as the catalyst for a renewed interest in heritage conservation and pride of place.

Since the Shaw Festival emerged, Niagara-on-the-Lake has flourished, contributing over $75 million to the local economy each year. the Shaw Festival – while spending money locally on accommodations, restaurants, shops and attractions.

Throughout the centuries, the towns of Stratford and Niagara-on-the-Lake have each contributed to Ontario’s heritage in unique and compelling ways. Yet each place has also influenced the founding of their festivals through economic circumstances, geography and supportive communities. As these festivals grew and prospered, so too did the communities. It begs the question: Who saved whom?