Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

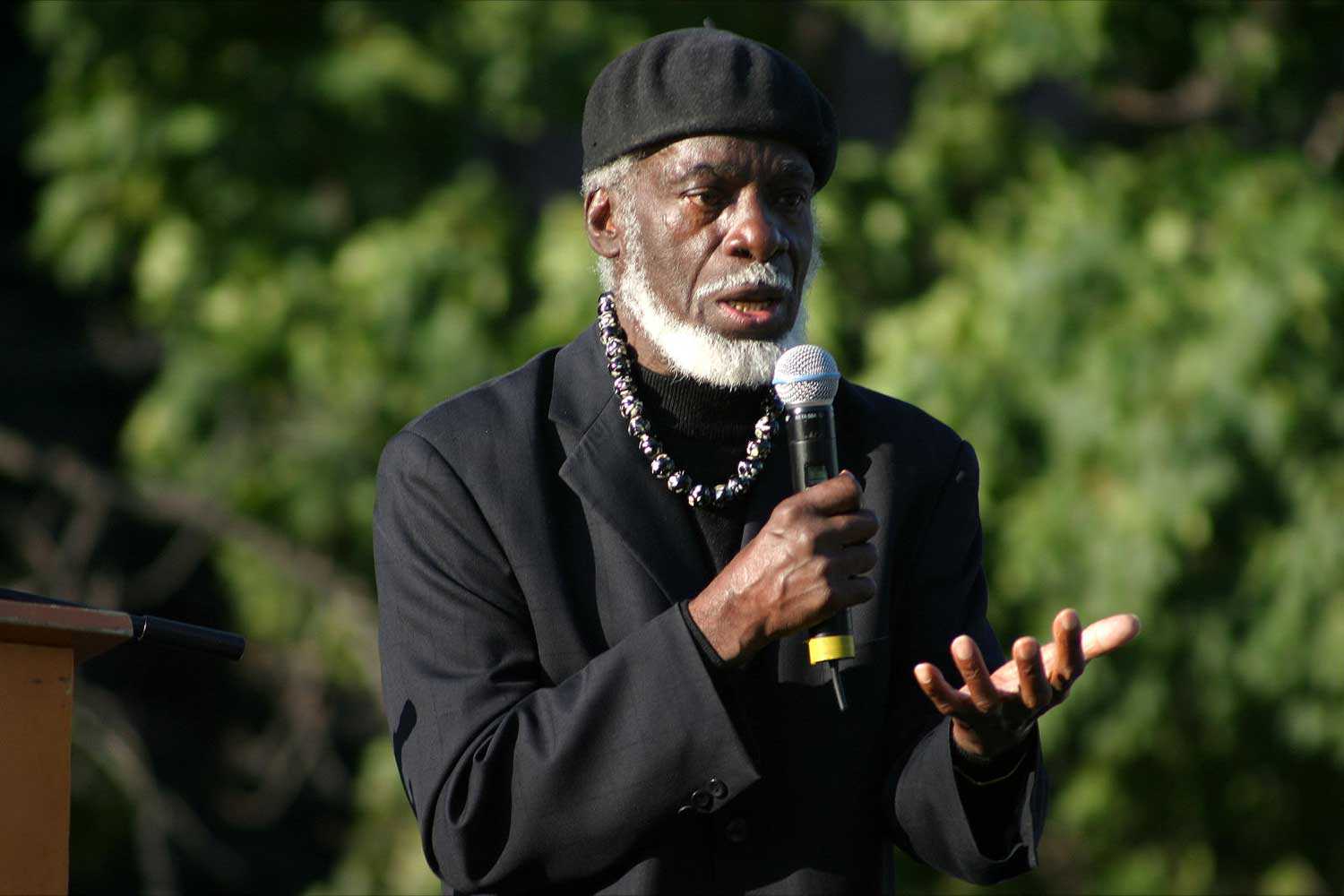

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

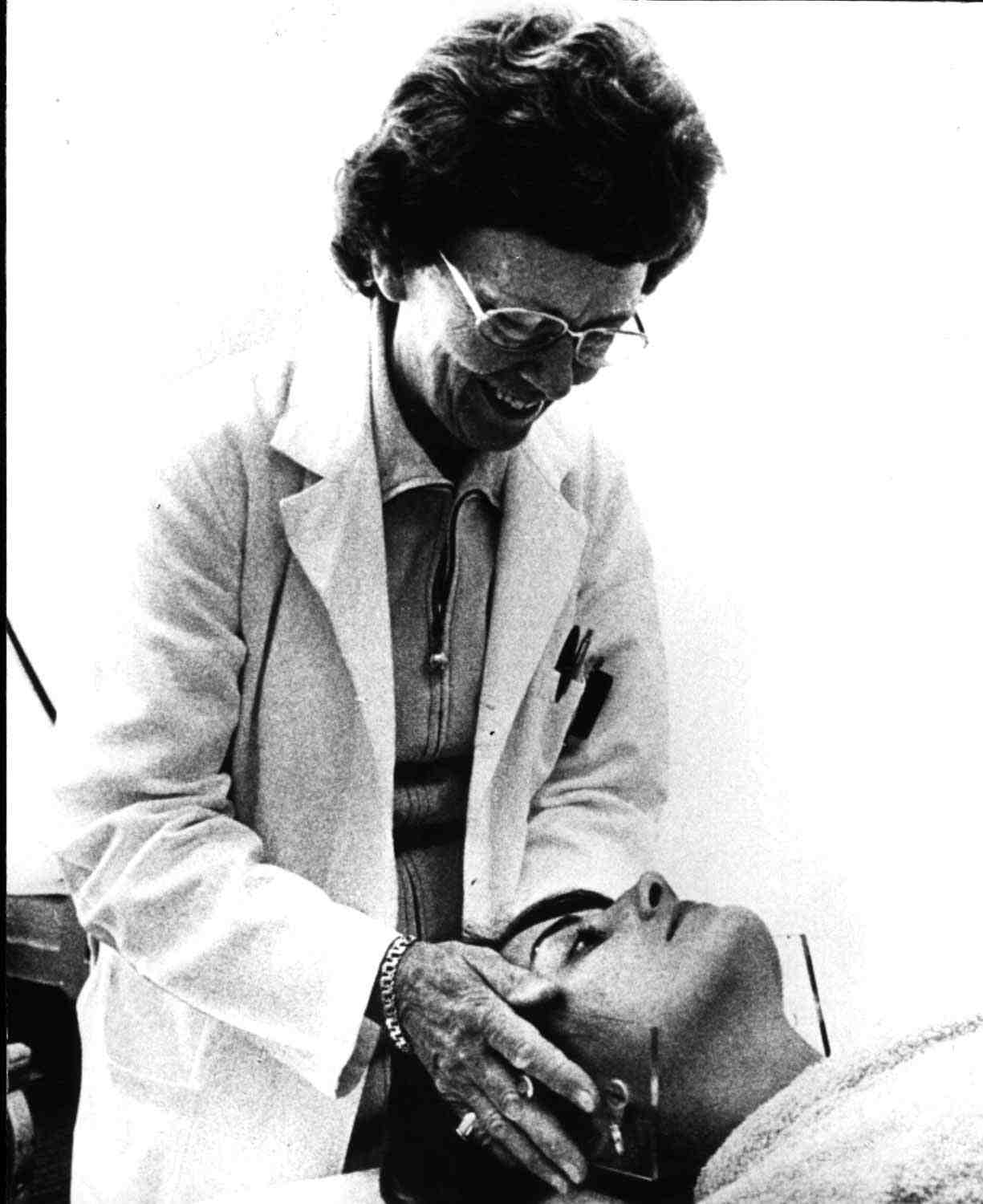

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

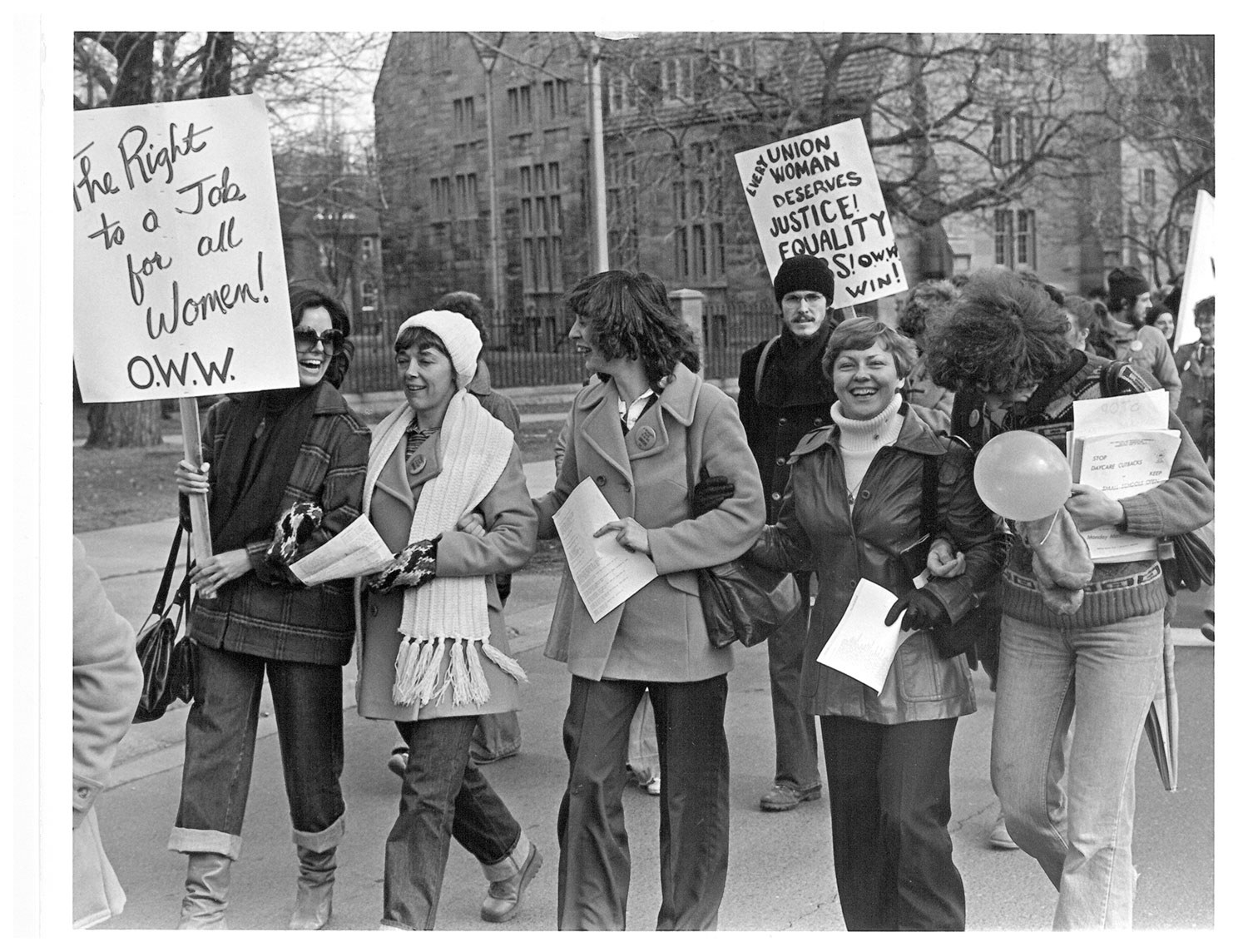

- Women's heritage

We’ve always been here: Black women’s history of voting rights and politics in Canada

Women's heritage, Black heritage

Published Date: Mar 20, 2018

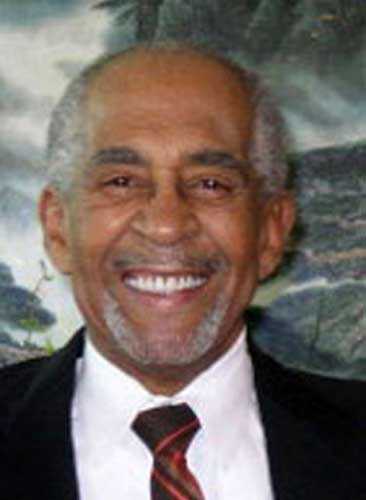

Photo: F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.

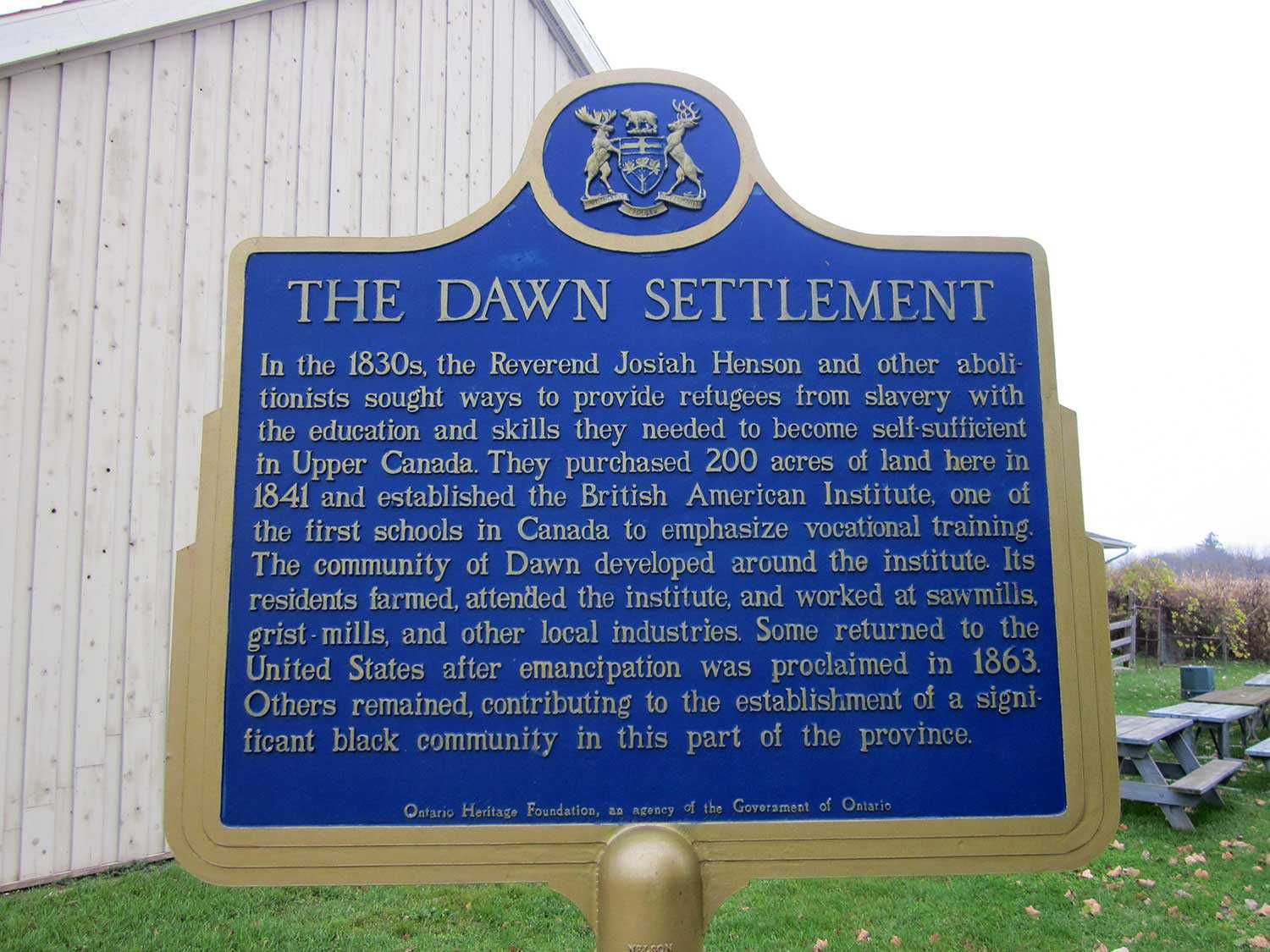

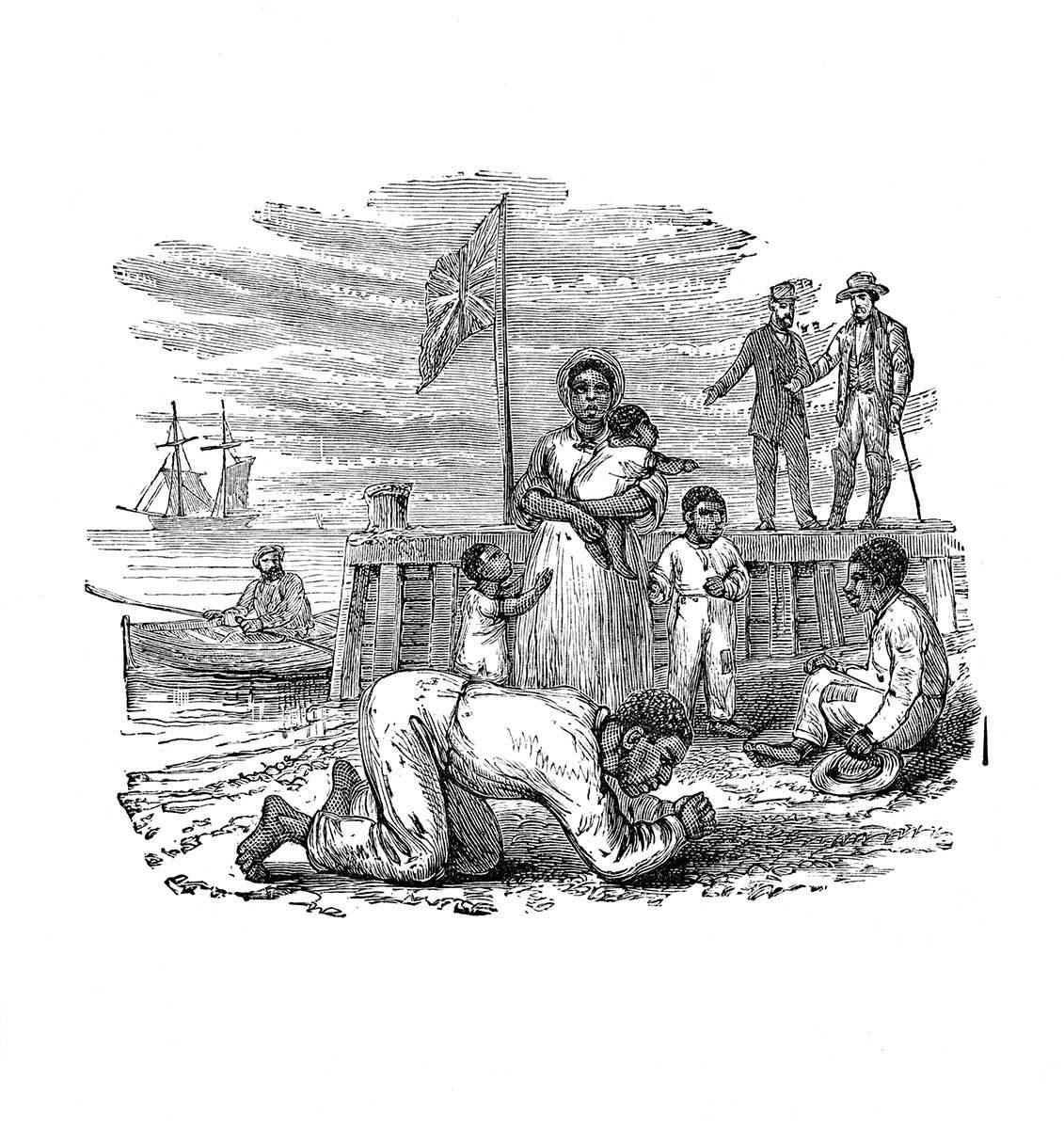

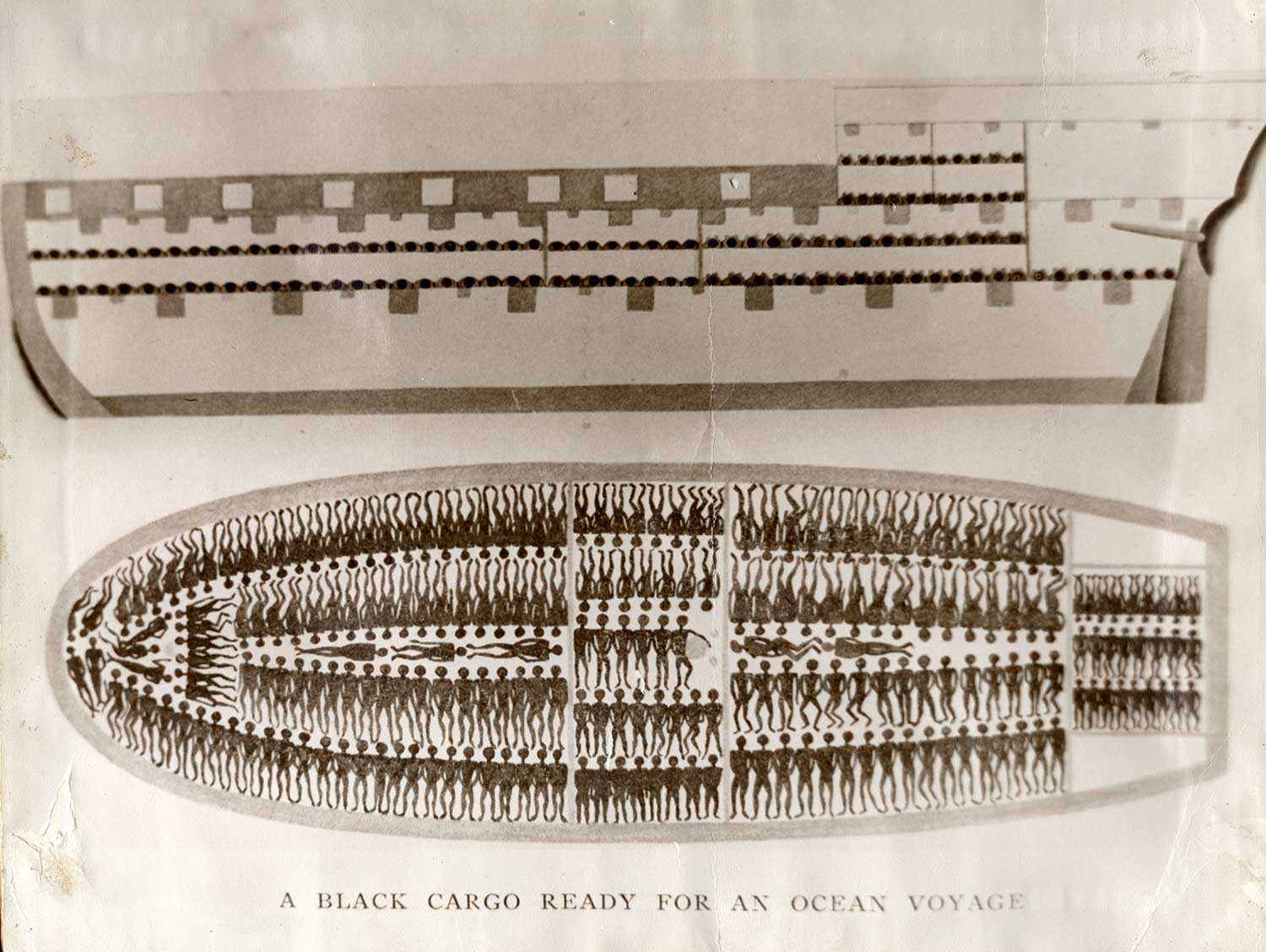

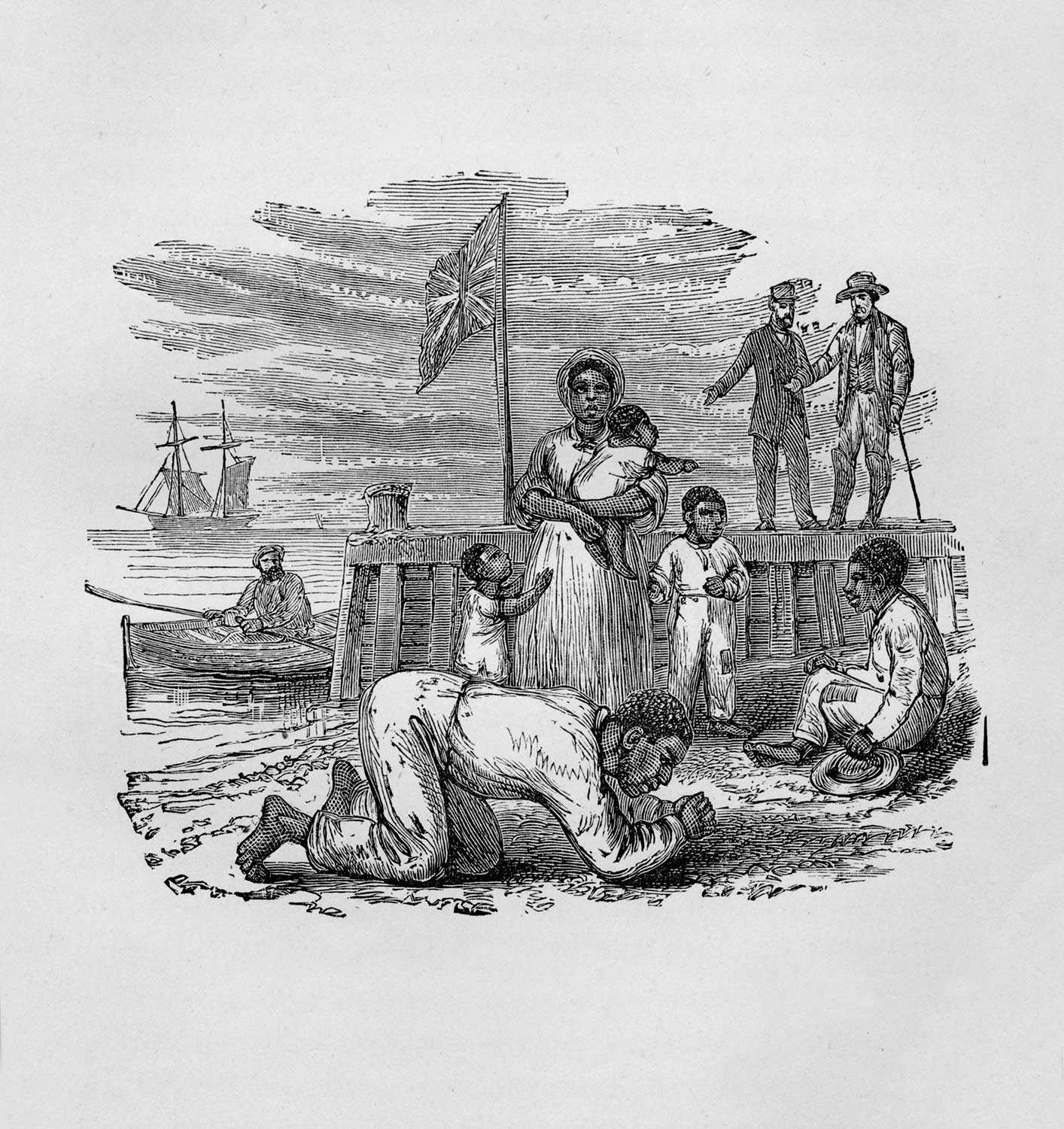

The history of Black women’s voting rights in Canada must be understood in the context of their evolving social status in the nation’s preceding French and British colonies between 1600-1834 through to the 20th century. Enslaved and legally deemed chattel property (personal possessions), Black women and men were not legally “persons” with any rights or freedoms and thus could not vote. After the abolition of slavery in most British colonies in 1834, including those in what is now Canada, Black women’s status changed to British subjects. While Black women were technically entitled to the rights, freedoms and privileges that their citizenship status carried, before 1917 that did not include the right to vote in provincial or federal elections.

F 2076-16-5-1-38/Baptist Sunday School group in Amherstburg, Ontario, [ca. 1910], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027813.

Black women get the vote

Black women did not face legal barriers to voting because of their race, unlike other racialized women. Black women, like white women, were able to exercise the right to vote in the mid-19th century. Black women, married or single, could cast their vote for school trustees beginning in 1850 and in most Canadian municipal elections by 1900 as long as they met the general eligibility criteria. They had to be able to prove their citizenship status as British subjects and later Canadian citizens, born or naturalized and they had to own taxable property of a certain value. Limitations placed on [white] women voters in provincial and federal elections also applied to Black women until 1917.

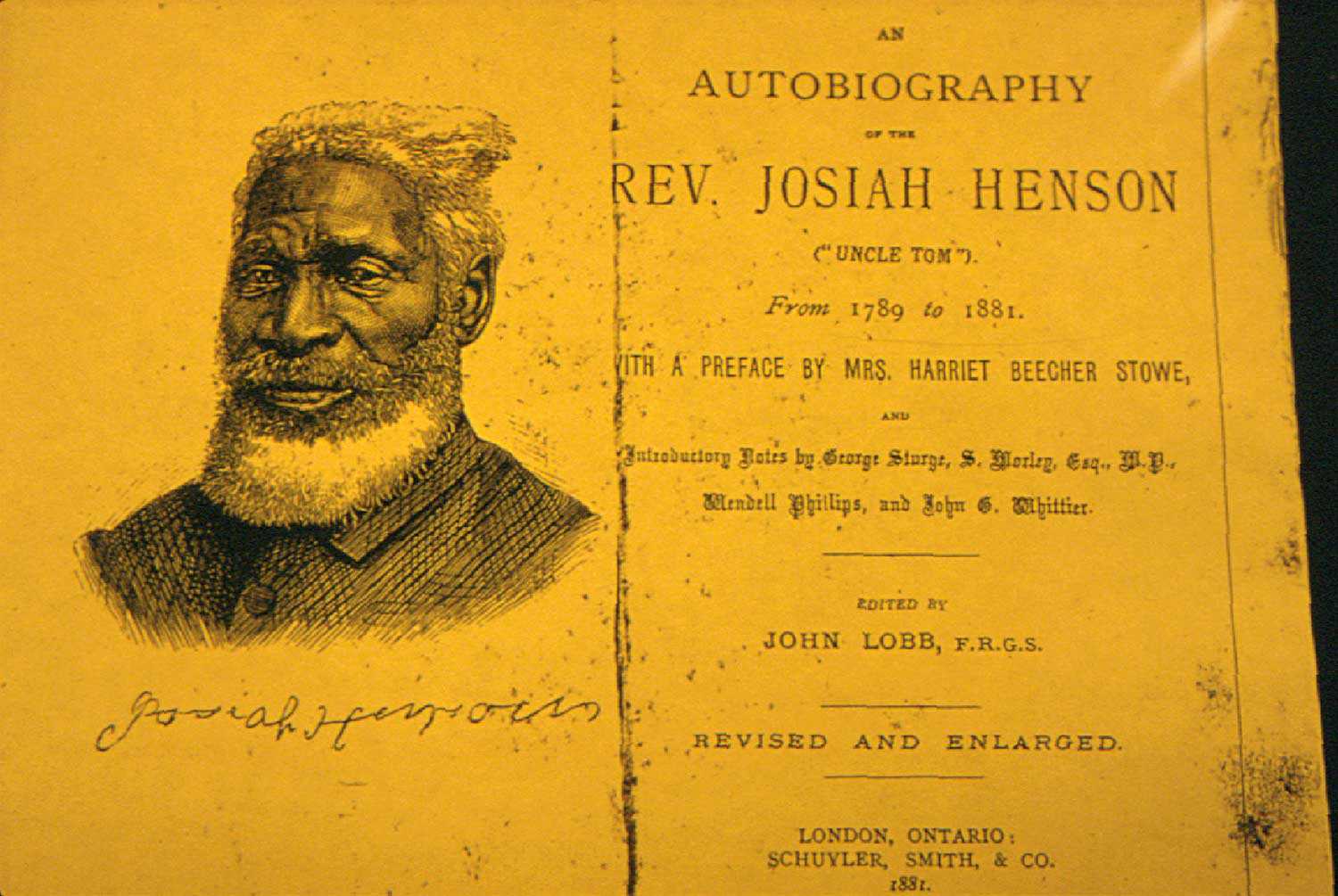

Black women actively participated in the suffrage movement. In the 1850s, Mary Ann Shadd Cary used her newspaper, The Provincial Freeman, as a transnational platform to discuss women’s rights, including women’s participation in political meetings, and the right to vote. Shadd also used the weekly newspaper to inform readers of suffrage meetings held in Canada and the United States. In August 1854, Shadd published her observation of a meeting of voters in Chatham. She noted that she “[a]ttended the meeting held by the voters, last night, at Chatham, at which I saw quite a large number of females. I like that new feature in political gatherings, and you will agree with me, that much of the asperity of such assemblies will be softened by their presence.”

During the mid-19th century, the struggle for the abolition of enslavement in America and full civil rights for those once enslaved encompassed the right to vote. Some women of African descent fought to ensure that the franchise was extended to them as well. This political advocacy extended to female freedom seekers who migrated to Canada.

At the height of the women’s suffrage movement at the turn of the 20th century, Black women were actively involved in agitating for women’s right to vote. Similar to white women, the level of engagement by Black women in the movement to secure the franchise tended to be influenced by their socio-economic background. Black women involved in such mobilization efforts tended to live in urban centres, were more often educated and financially secure. It is important to note that Black women’s struggle for the franchise was largely along racial lines. The wider women’s suffrage movement focused on securing the vote for white women and was not inclusive of agitating for the voting rights of racialized women – Black, Indigenous and Asian women. At least three members of the celebrated members of the Famous Five – Nellie McClung, Emily Murphy, Irene Parlby, Henrietta Muir Edwards and Louise McKinney – early champions of female suffrage and rights, held views of racialized peoples including Blacks, Indigenous, Chinese and Jews as being socially inferior.

The Wartime Elections Act of 1917 granted the federal franchise to the female relatives of men in serving the military (army or navy, active or retired). This law extended the right to vote to Black women related to men serving in the No. 2 Construction Battalion (the segregated all-Black labour unit in which over 600 men served from across Canada) and to the female relatives of Black men who were able to enlist in regular regiments.

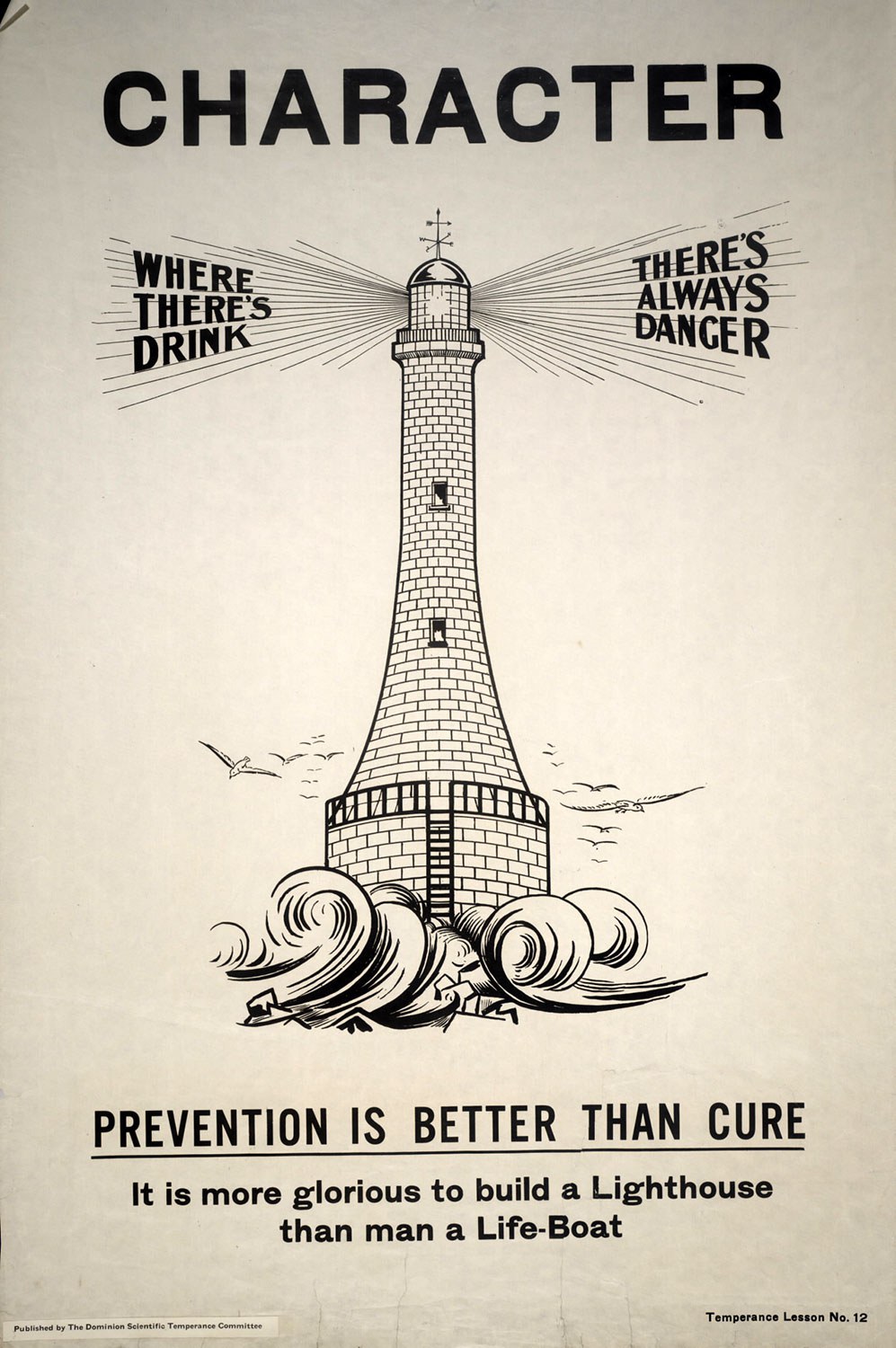

Over time, Black women became more involved in the political process and community organizations run by Black women added voter engagement to their mandate. At a 1924 meeting held by the Women’s Home and Foreign Mission Society of the Baptist churches in Windsor, the group asserted that, “We as Christian women will use our influence in this next election to keep the Ontario Temperance Act in force.”

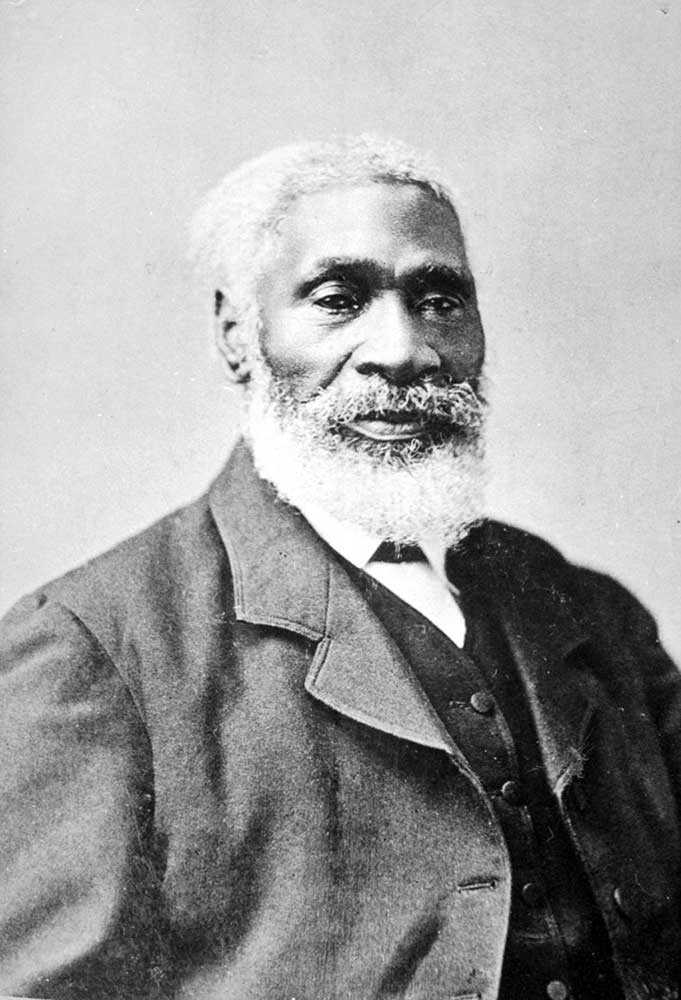

The right to vote and participate in the political process has been important to Black women and men in Canada throughout Canadian history. After over 200 years of enslavement and despite the continued anti-Black racism that they experienced, Black Canadians firmly believed that voting affirmed their status as British subjects and later as Canadian citizens; it enabled them to assert their political voices.

Black women have pushed the margins against the social constraints imposed on them and have inserted themselves in political spaces from which they were once excluded. The political engagement and activism of Black women in Canada has been and continues to be shaped by their experiences of gender and race.

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)