Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

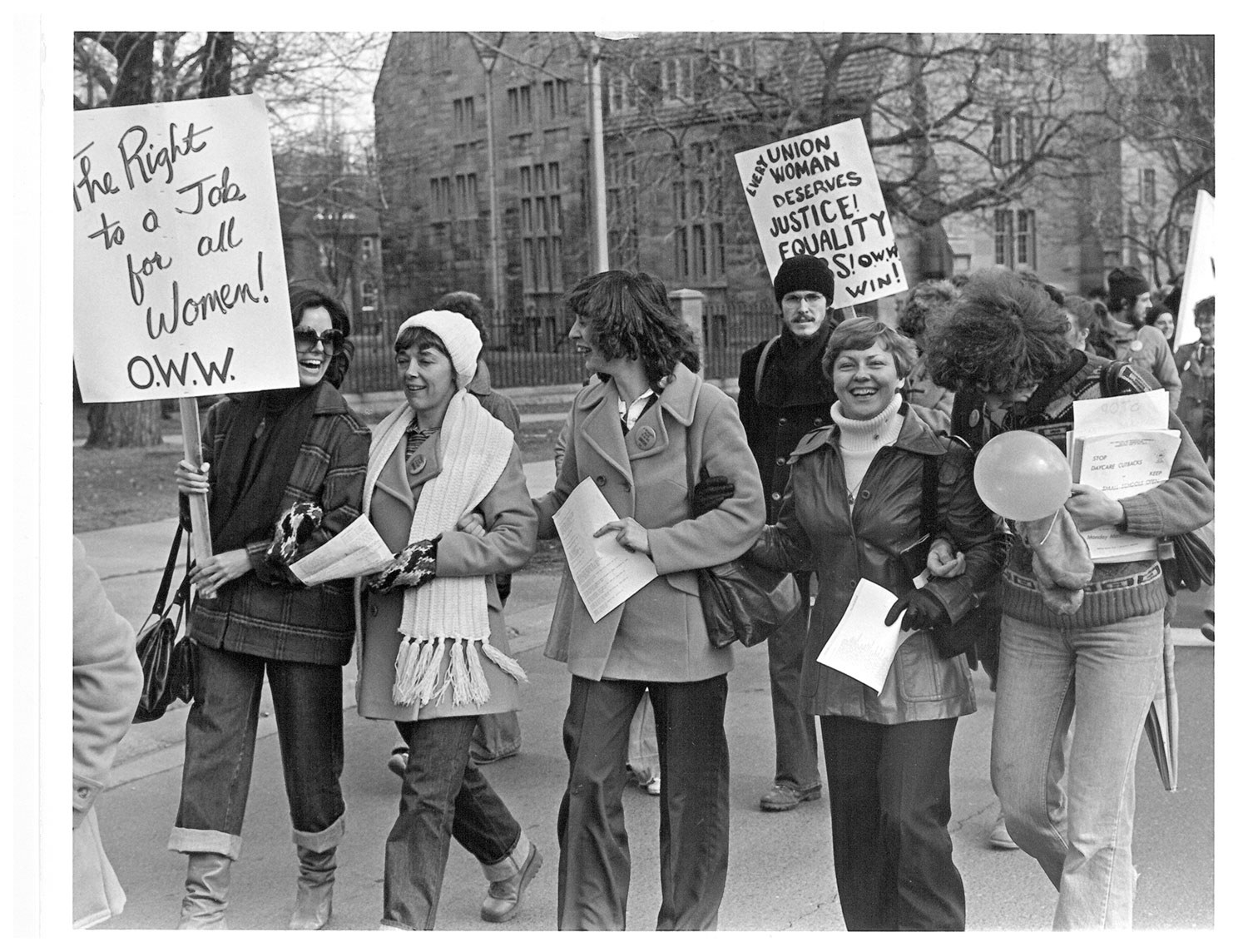

- Women's heritage

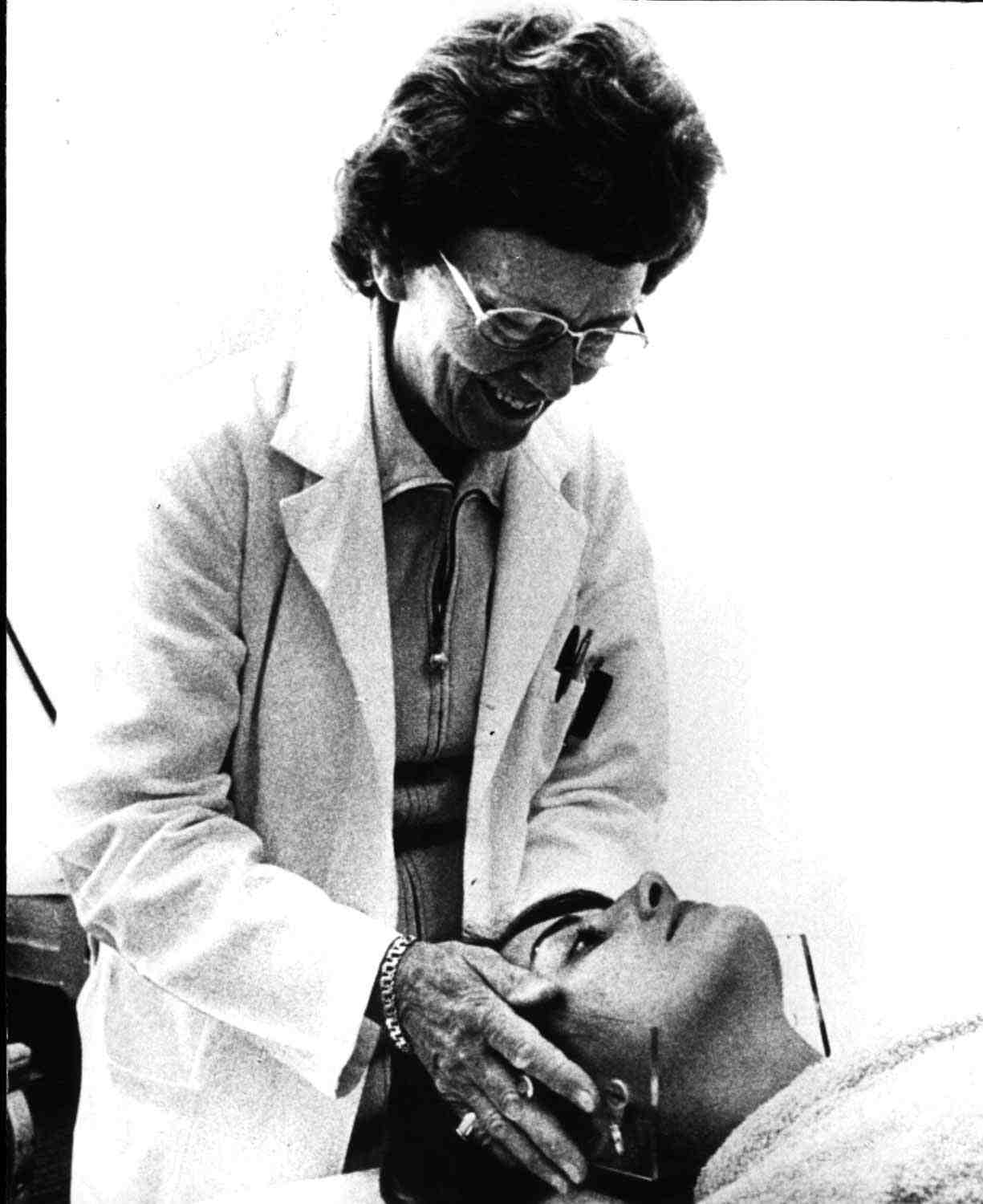

Vera Peters and the fight against breast cancer

Today, women with early breast cancer are usually treated with breast conserving therapy (removal of the cancerous lump followed by radiation). This approach is a relatively recent innovation that only became commonplace in the 1990s. Before then, women were subjected to radical mastectomies, an operation that cured cancer but left women disfigured and in pain. Toronto’s Dr. M. Vera Peters played a pivotal role in this transition.

Vera Peters was born in 1911 on a farm in Thistletown, outside Toronto. She entered the University of Toronto at age17 and, after a brief period studying math and physics, switched to medicine – one of only 10 women in a class of over 100. She supported her studies by waitressing on a cruise ship, where she met her future husband, Ken Lobb, a high school physical education teacher.

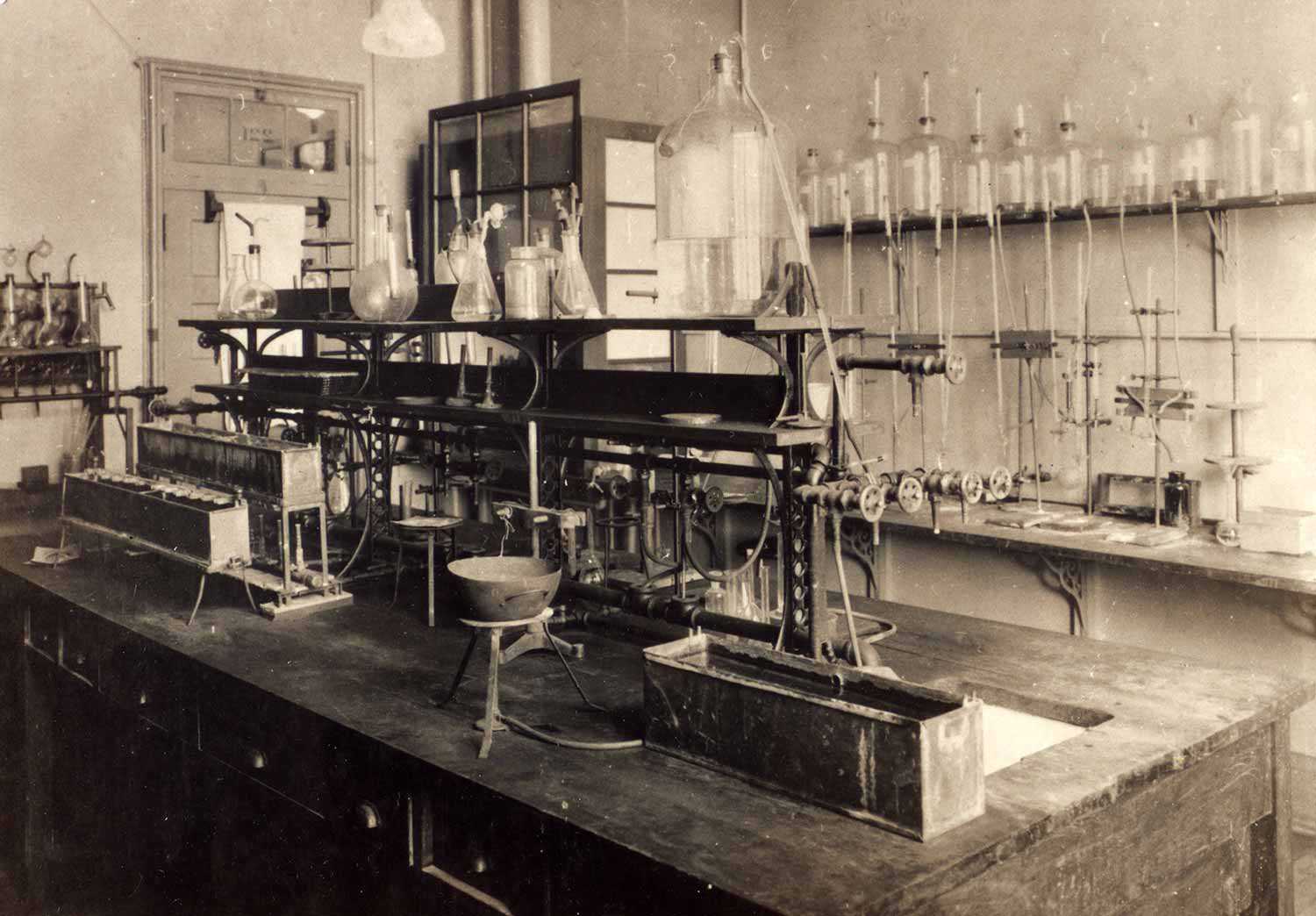

While she was a medical student, Peters’ mother died of breast cancer. This event was a turning point in her life. Through her mother’s illness, she met her future mentor, Dr. Gordon Richards, the head of radiotherapy at Toronto General Hospital. Peters had been fascinated by Richards’ lectures, and her personal connection through her mother’s illness crystallized her desire to enter the new field of radiation oncology.

After graduating from medical school in 1934, Peters joined Richards first as his apprentice and later as his assistant. She was to spend the remainder of her career in Toronto – first at Toronto General, later at Princess Margaret Hospital.

Her first major scientific contribution occurred in 1947. Richards asked her to review the hospital’s experience with Hodgkin’s disease. Peters embarked on a review of the associated cases treated at Toronto General and, in 1950, published a landmark paper that demonstrated that Hodgkin’s disease could be cured with radiotherapy. She also found that the extent of the disease at the time of diagnosis was the most important factor influencing survival. Her staging classification was the foundation for the staging system still used today. While her results were met with scepticism, most physicians eventually became convinced that Hodgkin’s disease was curable.

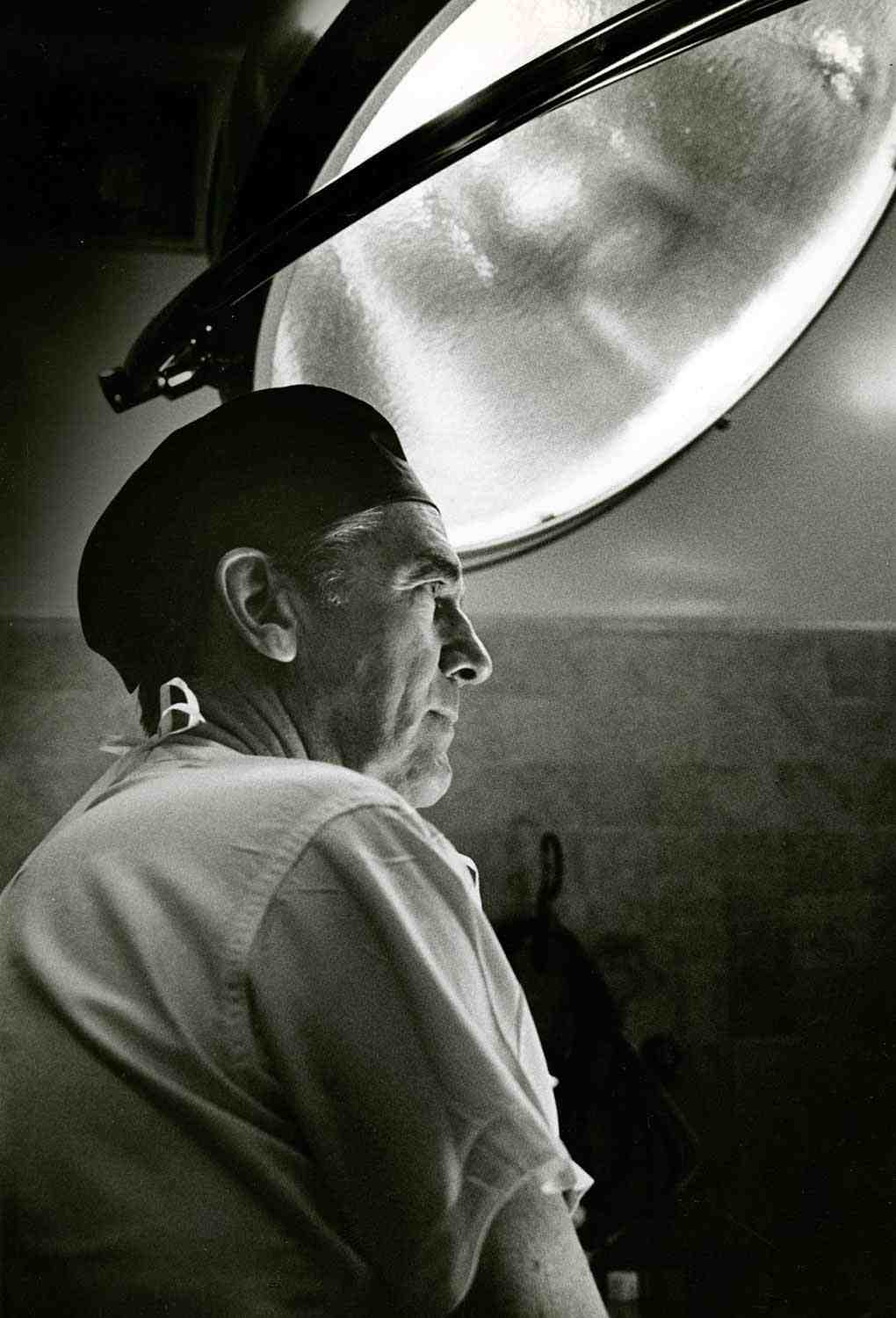

Peters’ second major contribution was in breast cancer treatment. When she began her career, the standard treatment for breast cancer was the radical mastectomy – the removal of the breast, skin, nipple, tissues in the armpit and chest muscles. As a woman, she was sensitive not only to the physical ravages of mastectomy, but also to what she called the “associated emotional trauma.” She witnessed the devastating effects on body image, sexuality and femininity.

Peters became determined to find a gentler approach. She was aware that, over the years, a number of Toronto women had been treated with lumpectomy (removal of the tumour) followed by radiation, but it was unknown whether this procedure cured as many women as mastectomy. With quiet resolve, she embarked single-handedly on a review of 8,000 cases of breast cancer treated in Toronto since 1939 and found that women treated with lumpectomy and radiation had the same cure rate as women who had undergone mastectomy. Her findings – first presented in 1975 – were met with hostility by the surgical establishment. It was only when a large American study confirming her results was published in 1985 that surgical practice slowly started to change.

Peters retired from Princess Margaret in 1976 and started a consulting practice in Oakville. In 1984, she was herself diagnosed with breast cancer and, true to her convictions, was treated with lumpectomy. Nine years later, at the age of 82, she was diagnosed with lung cancer. She received palliative radiotherapy and died on October 1, 1993 at the hospital where she had spent most of her career – Princess Margaret.

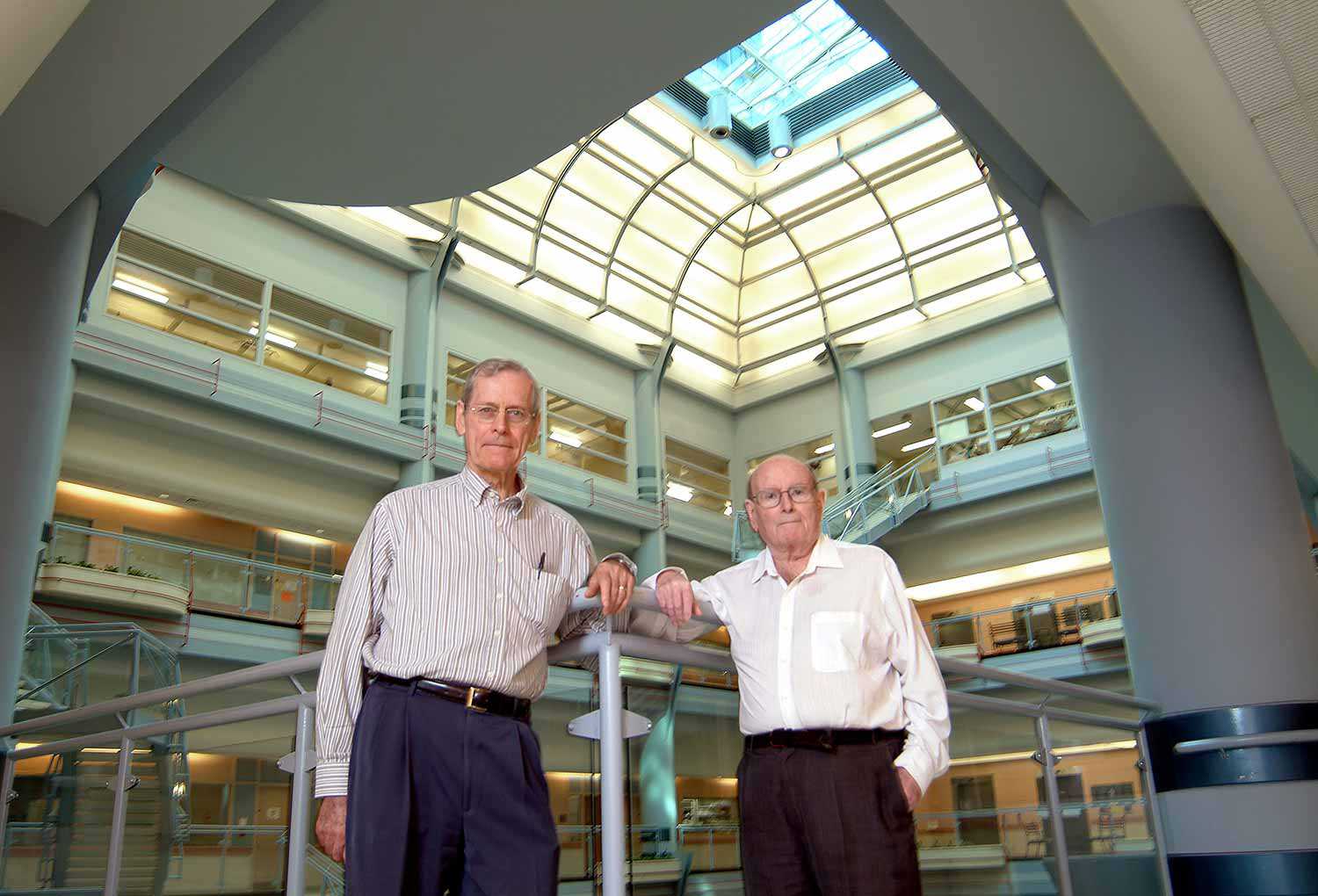

During her lifetime and after, Peters was widely recognized for her achievements. In 1975, she was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada. In 2010, she was inducted posthumously into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame. The Peters-Boyd Academy at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine is named in her honour.

Peters is remembered by her former students not only as a compassionate physician who always put patients first, but also as a pioneering role model at a time when there were few women in the top ranks of medicine.

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)