Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

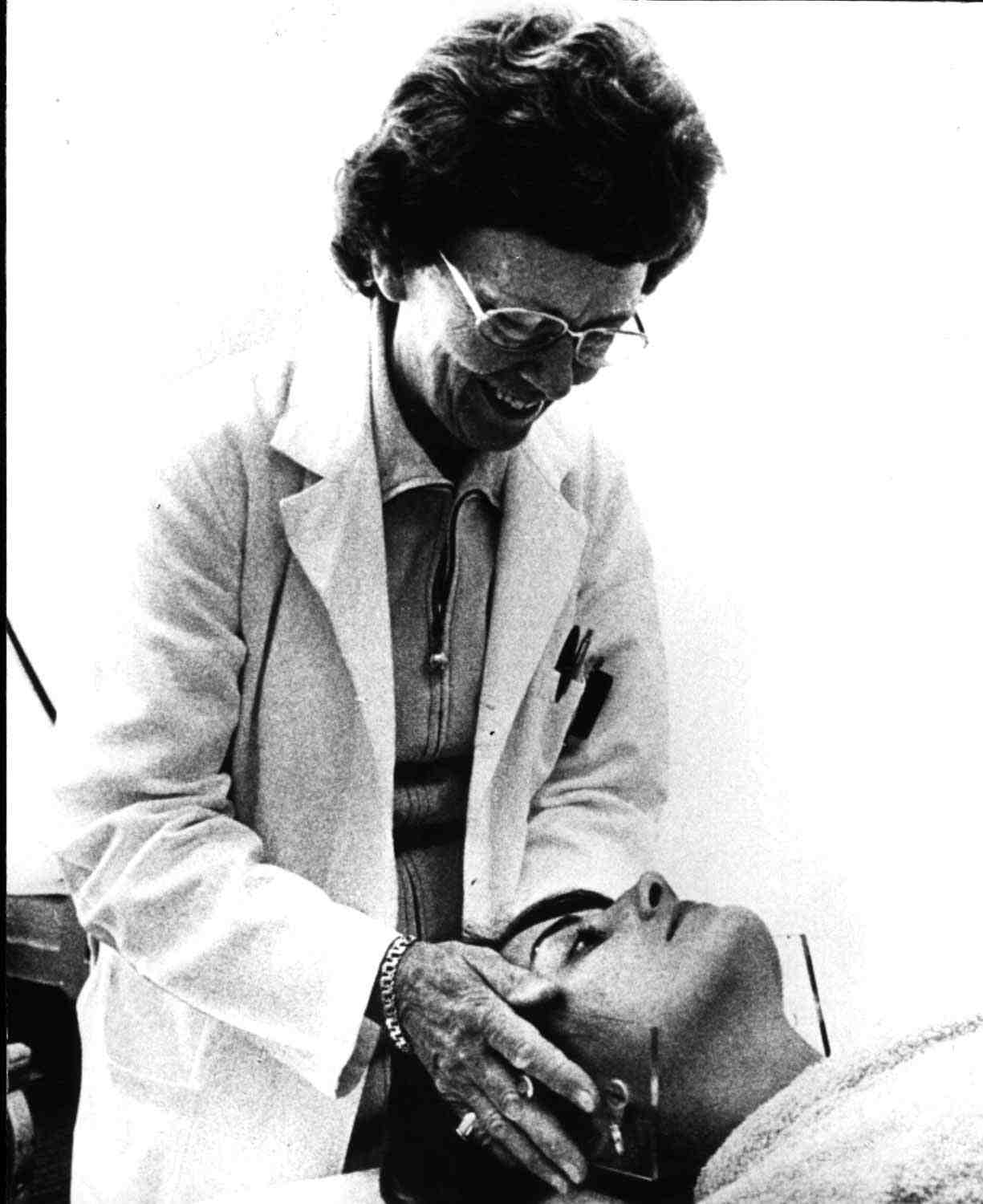

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Women in organized labour

Before the First World War (1914-18), women had few rights and they could not vote or hold public office. Policies were overtly discriminatory toward women in the workplace. Women were limited in the jobs that they were allowed to hold – lowpaying factory jobs (often in the textile industry), teachers, nurses or domestic workers. Starting in the 1920s, women were employed in greater numbers in clerical and sales clerk positions and factory work that was often dangerous. Women began to join the labour movement, with early action focused on better wages, hours and working conditions. Early strike action took place at the Toronto Carpet Factory in 1902 where women fought for a 55-hour work week, and in 1907 at Bell Telephone where 400 women operators walked off the job in protest to increased hours at lower wages and poor working conditions.

During the First World War and the Second World War (1939-45), women replaced men in manual labour jobs at factories. During this time, many factories were producing munitions in support of the war effort, and women were a source of cheap labour. At the end of the Second World War, some women were encouraged to leave their positions and others were legislated to leave. There was by no means a mass exit of women from the workforce; in the early 1950s, about 25 per cent of women participated in the labour force and, by the mid-1970s, that number increased to about 40 per cent.

The 1970 Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada made several recommendations relating to employment equality, but women labourers were still virtually non-existent in some industries, such as steel-making, mining and skilled trades. Women who continued to work in factories and in manual labour were often relegated to the lowest–paying jobs with very poor working conditions.

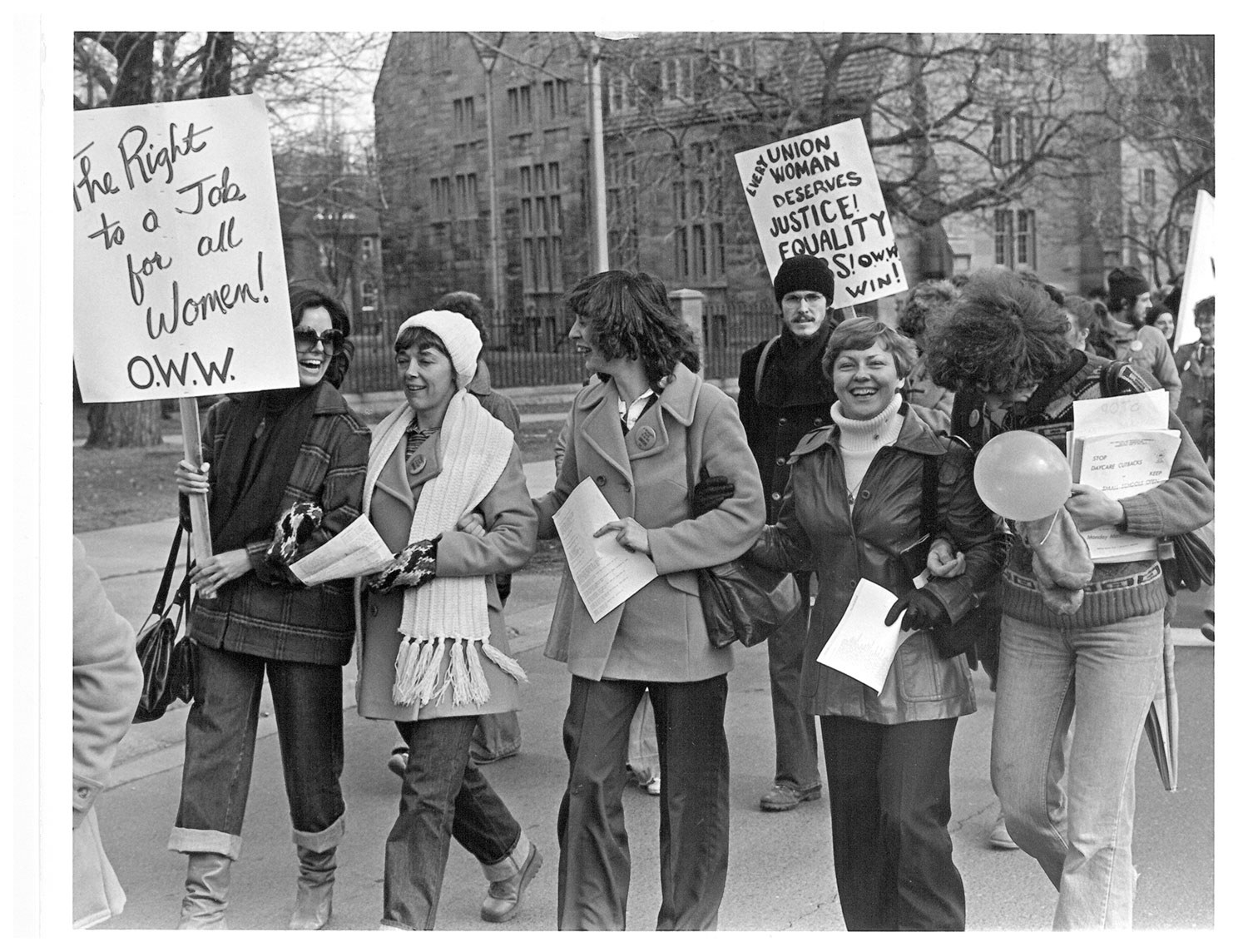

During the 1970s and 1980s, Ontario’s organized labour movement became an important supporter of women’s equality in the workplace. In Ontario alone, there were a number of strikes and labour disputes at female-dominated employment sites, including Fleck Manufacturing near London, a Radio Shack warehouse in Barrie, and several Eaton’s stores in southern Ontario.

The women of Fleck Manufacturing faced unsafe working conditions, low pay and harassment from supervisors. In 1978, the women at Fleck Manufacturing organized a new United Auto Workers Local (UAW) 1620, which went on strike when the company refused its demands. In the late 1970s, UAW membership was 90 per cent male, but the five-month-long strike at Fleck was organized and led by women. These same women led the International Women’s Day Parade in 1979. The eventual victory at Fleck Manufacturing had positive impacts for locals throughout the UAW, bargaining to acquire maternity leave, sexual harassment protection, childcare support and affirmative action.

In other sectors such as steel production, women were fighting to get back onto jobsites where they worked during the Second World War. The Women Back into Stelco committee was started by the United Steel Workers when five women launched a sex discrimination complaint against the company with the Ontario Human Rights Commission in 1979. Stelco employed 12,000 people, but only 28 women worked in production in female-designated jobs, mainly tin inspection. Not one woman was hired at Stelco between 1961 and 1977. It is unknown how many women applied for jobs at Stelco during this time period, but estimates range from 10,000 to 30,000 female applicants, without a single one being hired. The women won their case and Stelco hired 180 women. While the majority of these women were laid off in the early 1980s, Women Back Into Stelco was still a significant campaign because it compelled a major employer to change their hiring practices and gave women access to higherpaid industrial jobs.

The above are just a few examples of how organized labour has encouraged women in the slow and sometimes arduous climb to equality in the workplace. The fact is that equality has still not been reached. One way to measure this is the gender pay gap, which still exists in Ontario. As a union steward, I was interested to know that 2015 statistics show that the hourly gender wage gap is 7 per cent for those with union coverage and 18 per cent for those with no union coverage. The wage gap is more pronounced for Indigenous and racialized women and those with disabilities. In 2018, we must strive to do better for all women.

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)