Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

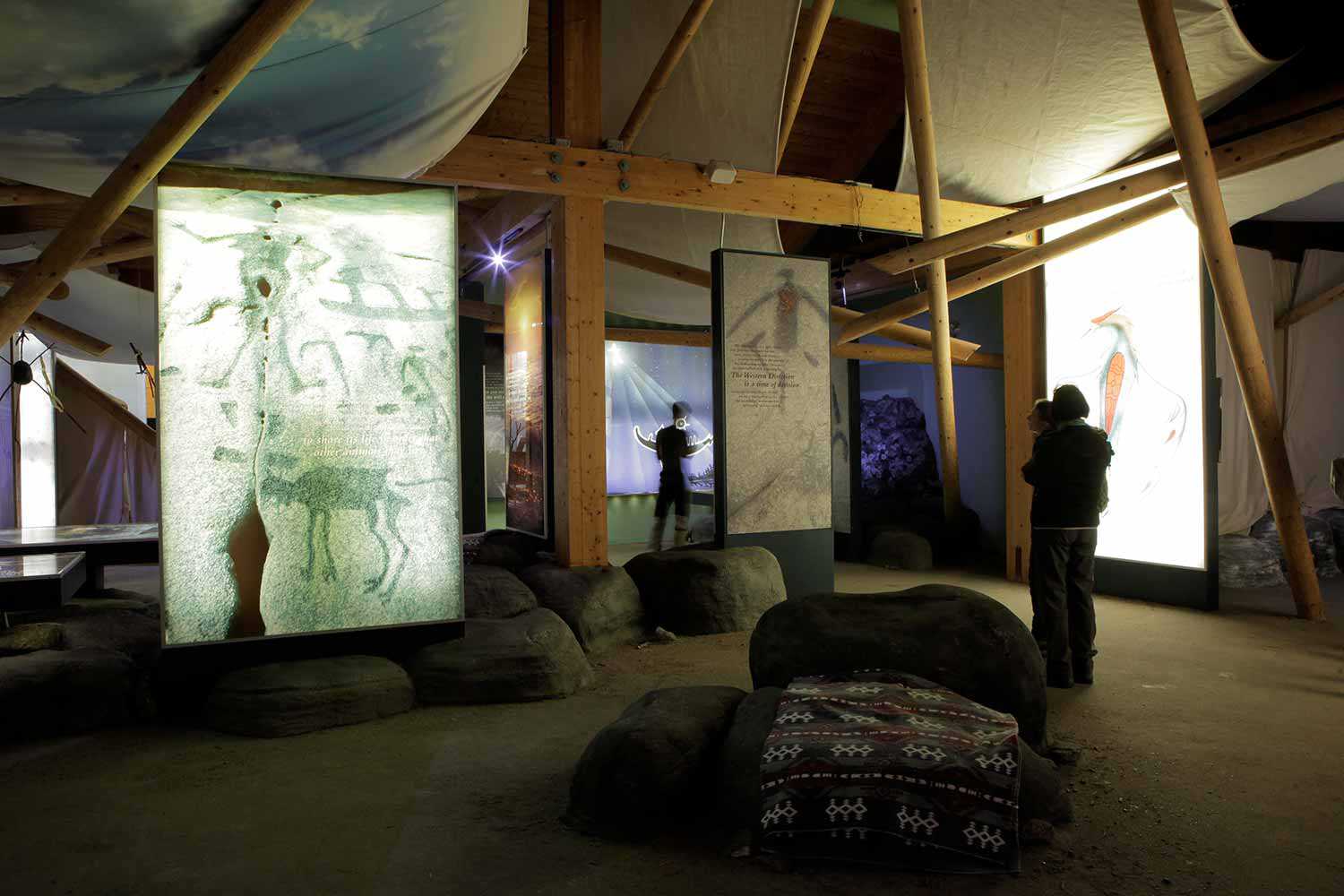

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

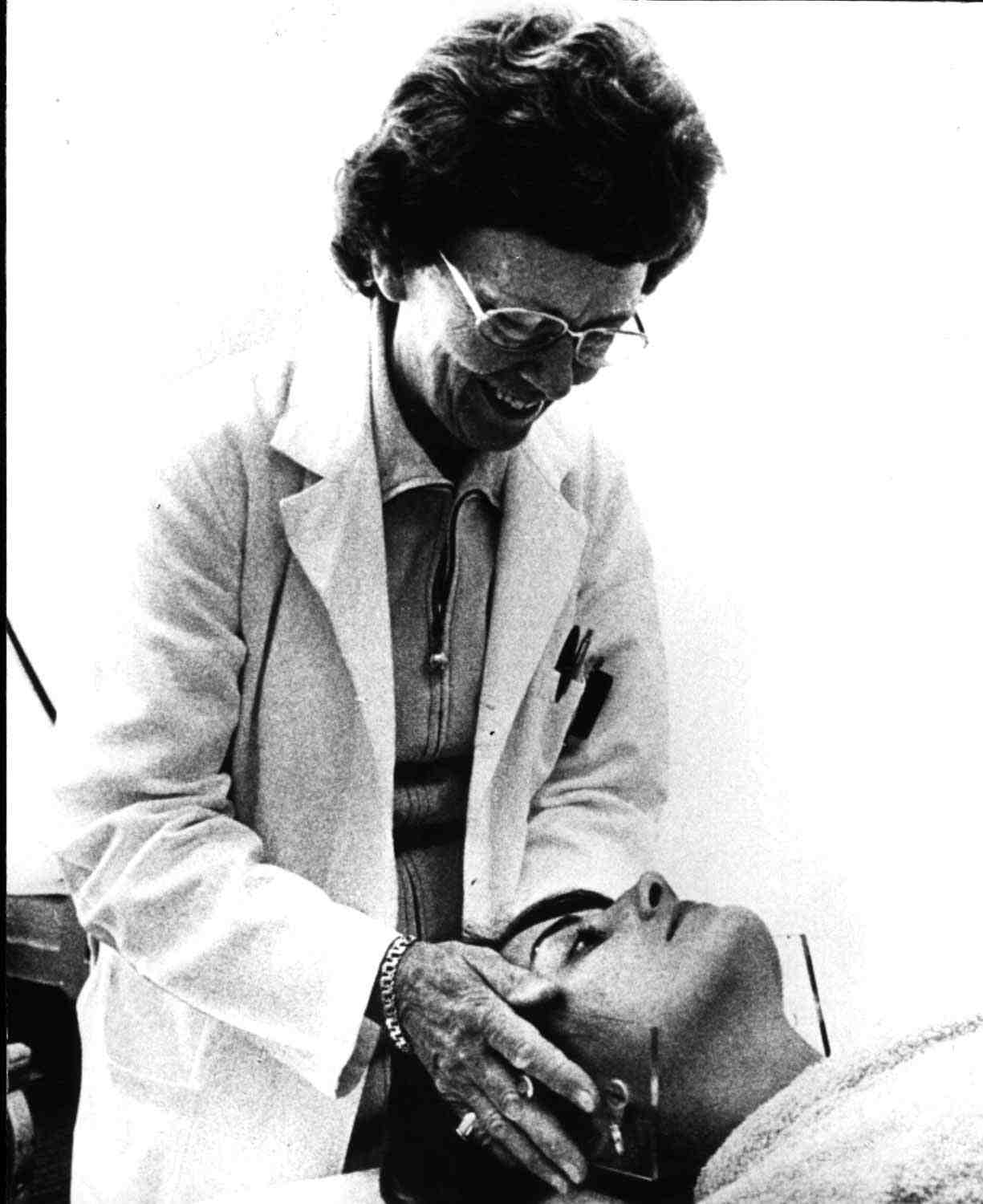

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

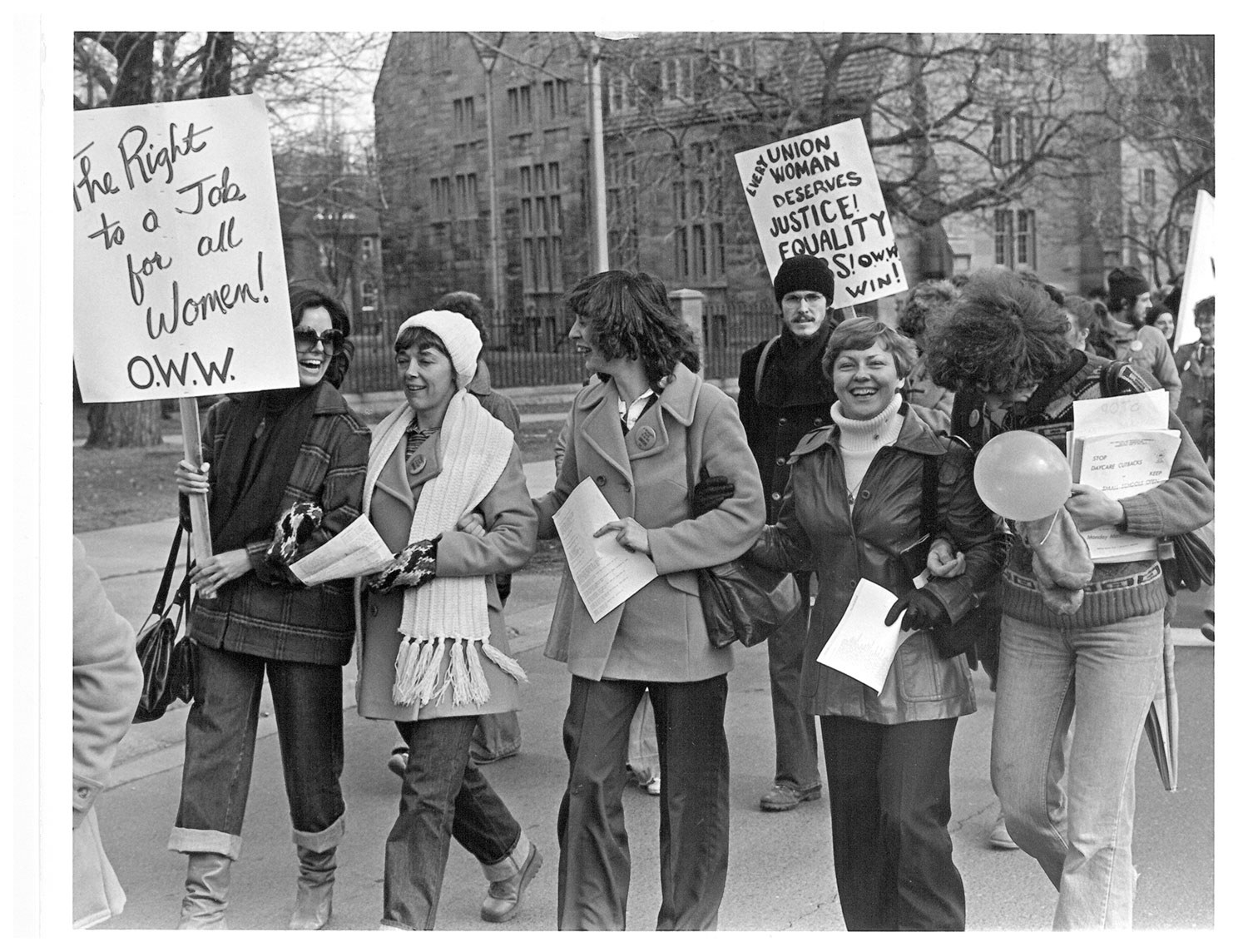

- Women's heritage

Kit Coleman: Journalism pioneer

Kathleen Blake Coleman, known to her readers as “Kit,” stood out among Ontario’s women journalists of her day because of her obvious talent, lively writing style and willingness to travel and report from abroad, notably Cuba during the 1898 Spanish-American War. Born in County Galway, Ireland in 1856, she was the daughter of struggling tenant farmers but received a very good education. Her family arranged her marriage to an older, wealthy man, a common occurrence in Ireland then. But he did not provide for her in the event of his death, and she immigrated to Canada as a young widow, looking for a new life in the early 1880s. In Toronto, she survived a second, unhappy marriage to a travelling salesman that produced a son and a daughter, whom she financially supported as a single parent. She was first hired by the Toronto Daily Mail in 1889 as editor of its new “Woman’s Kingdom” page.

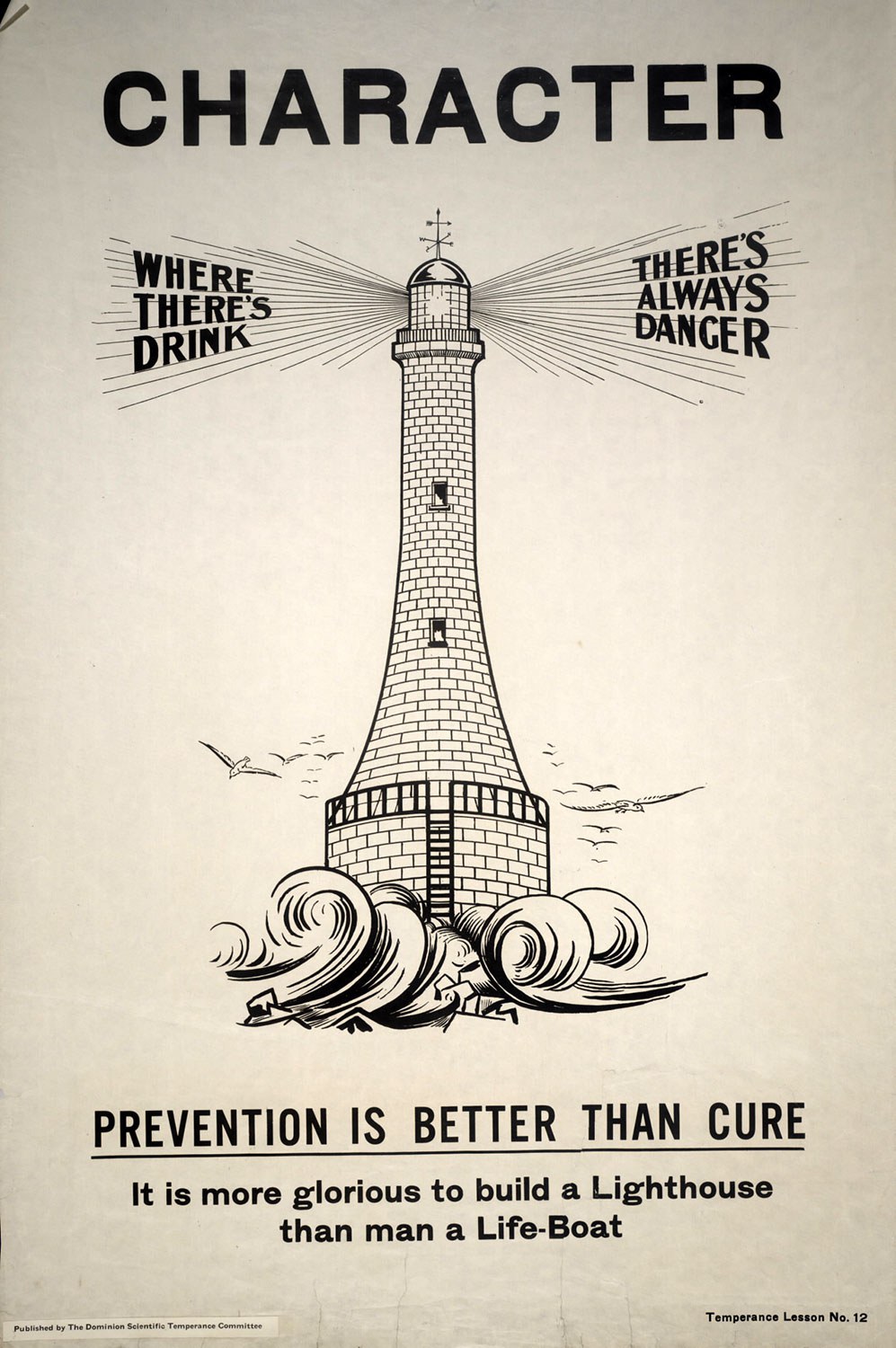

Coleman was one of the first women to benefit from a period of strong growth in the newspaper industry. Big and small business provided the advertising to finance the dailies, the technology that produced them became more sophisticated, and the Ontario government emphasized the importance of literacy and school attendance so that more people were reading them, boosting circulation. The space that opened up for female journalists on the newspapers was gender specific, however, in line with the popular thinking that women naturally excelled in the domestic sphere and should stay there. The women’s pages were born of the owners’ business decisions to attract female readers and the advertisers of household products that catered to them.

Women’s page jobs attracted intelligent, educated women who were actually interested in more than just household hints, recipes and child-rearing tips. A number of them tried to write about issues beyond the domestic sphere, with varying degrees of success, depending on how much opposition they faced from their editors, advertisers and readers of both sexes. Her least favourite topic was fashion; she preferred to write about politics, business, science and social issues when she could get away with it. She also started a popular advice column. Because of her following among both women and men, she survived a merger with another Toronto newspaper in 1895, under the new masthead, the Mail and Empire.

Mail and Empire building, northwest corner of Bay and King streets, Toronto. Photo: City of Toronto Archives.

Coleman was able to venture outside of the women’s sphere from time to time by covering high profile, scandalous court cases and travelling abroad and writing about her adventures. Notably, she dared to go to Cuba during the 1898 Spanish-American War as an accredited female war correspondent – apparently the American government’s first. It was a circulation stunt to attract readers and earned her an international audience. The army commanders on the ground were opposed to her presence and she was stranded in Florida until she was able to make her own way to Havana just as the war was ending. Undeterred, she wrote movingly about the destruction it wrought on the land, and on the people, including the soldiers. She was no fan of war.

Shortly after she returned from Cuba, she married for the third time and moved with her kindly husband, Dr. Theobald Coleman, to Copper Cliff in northern Ontario, where he was hired by the Canadian Copper Company. She wrote that she helped him nurse injured miners and deal with an outbreak of smallpox, urging a quarantine, publicity that neither the town nor the company welcomed. But, being a city person, she was not really happy there in the first place and the Colemans moved to Hamilton after the company let him go.

Kit Coleman was an inspiration to younger female journalists, and agreed to be the first president of the fledgling Canadian Women’s Press Club in 1906. She felt that women, married or not, had the right to receive equal pay for equal work, and to earn their own livings in case their marriages failed or their husbands died. To the dismay of some of her more feminist colleagues, she did not advocate for the contentious vote for women, most likely because of the Mail and Empire’s editorial stance against it. By 1911, however, when the suffrage movement was gaining ground in Ontario, she did support it in principle.

Around the same time, she fought with management over her unequal pay and workload and began a new career as a freelance journalist, selling her syndicated columns to popular newspapers across the country. But after her Cuba adventures, her health was no longer robust. In 1915, she died of pneumonia at the age of 59, a pioneering icon among her peers, inspiring generations of female journalists to continue fighting for respect in the news industry.

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)