Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

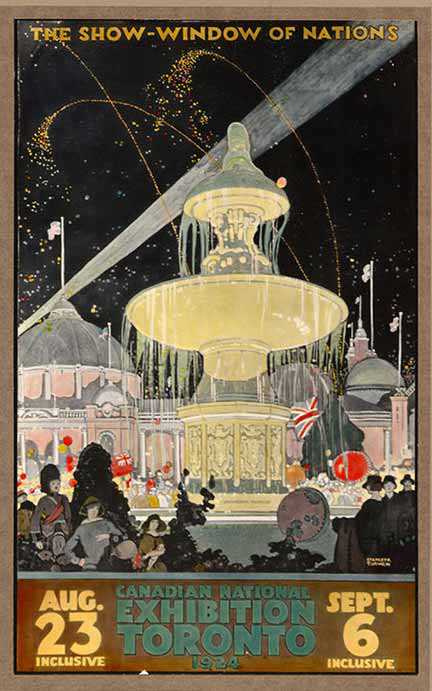

Communication firsts at the Canadian National Exhibition

The Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) was founded in 1879 for the purpose of fostering the development of agriculture, industry and the arts. Originally called the Toronto Industrial Exhibition, the name was officially changed to the Canadian National Exhibition in 1912 to represent better what the fair had become: “The Show Window of Nations.” The CNE grew to reflect the changes in Canadian society as the emphasis slowly shifted from traditional agriculture to industry, featuring timely exhibits on the latest technological advances.

Over the CNE’s 140-year history, the public experienced at the fair – often for the first time – many technological advances in telecommunications, radio, film and television. In 1879, one of the first telephones in Canada was on display, its capabilities demonstrated to the public by a Mr. Potter and Dr. Roseburgh. Almost a decade later, in 1888, Lord Stanley (the namesake of the famed Stanley Cup) was recorded on Thomas Edison’s Tinfoil phonograph as he addressed fairgoers at that year’s CNE.

In an advertisement in the 1910 CNE program, the Northern Electric and Manufacturing Company highlighted their Inter-Phones, promising to bring the convenience of instant communication to Canadian businessmen and farmers alike. They advised business executives to “Sit at your end of the wire and talk to your employees at the other end. Steps are minutes – save them.” For its residential audience, Northern Electric promised convenience and peace of mind. An advertisement for the Northern Electric Telephone in the 1914 CNE program guaranteed “Instant communications regarding Market Reports, Storms, Sickness, Assistance Needed, etc. ... Your house or farm can be kept in close touch with the outside world.”

In the 1920s and 1930s, Canada became even more closely connected through innovations in music, radio and television technologies. In 1920, the Marconi Company set up a radio transmitter in the Railway Building (now the Music Building) and broadcast music played on a phonograph to a receiving set in the Horticulture Building, approximately 100 metres (320 feet) away. Music was no longer restricted to a single room. In 1922, the Toronto Daily Star (now the Toronto Star) took it one step further, demonstrating wireless radio through their Radio Car, which travelled around the grounds broadcasting news of the world to thousands of people.

These kinds of demonstrations continued into the 1930s. Several radio stations, including CFRB and amateur radio station VE9CNE, would set up at the CNE for the duration of the Exhibition, transferring their entire broadcasting and studio operations to the fairgrounds. Features like the ABC of Broadcasting (1935) showcased the lifecycle of the radio broadcast, from where it began in the studio to how it reached radios in living rooms across the country.

In the realm of film and motion pictures, the Ontario Government played a large role in bringing scenes of the rest of the province to the city. In 1932, the Ontario Government Motion Picture Bureau presented “interesting short features” alongside news events from the preceding days, often within a few hours of their occurrence. By 1939, Canadians caught their first glimpse of television, through a demonstration by the Toronto Daily Star and RCA Victor, featuring a complete television studio. The first television appearance in the United States had occurred just a few months earlier, at the New York World Fair.

By 1941, other innovations such as facsimile transmissions (better known to us as faxes) and even artificial voice technology had made appearances at the CNE. Courtesy of Bell Telephone Company, Voder – short for Voice Operation Demonstrator – reproduced any tone or sound made by the human voice entirely through electrical currents. Specially trained telephone operators used a system of keys corresponding to the human vocal system to make the “uncanny mechanical voice”, dubbed Pedro, speak.

From 1942-46, the CNE closed its gates to act as a base and demobilization centre for the armed forces of the Second World War. By 1947, the Canadian National Exhibition was back up and running, showcasing the latest and greatest in communications technology – and other great strides in advancement – for millions of curious Canadians. From radar demonstrations in 1948, to the CNE Colour Network in 1964

(Canada’s first closed-circuit colour television network) to virtual reality simulations in 1996, the CNE was at the forefront of new communications technology.

In 2016, the CNE introduced the CNE Innovation Garage – a threeday event showcasing the best and brightest start-ups, new technologies and innovations. The Garage has become a place where fairgoers can touch, taste, feel and interact with innovators, harkening back to the CNE’s roots as the place to experience the latest and greatest in new technologies. As the world evolves, the CNE will continue to grow alongside it and always be a place to celebrate and showcase new technologies.