Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

The evolution of the agricultural cultural landscape

The agricultural cultural landscape visible today is a comprehensive record of the small- and large-scale changes in the industry that at one time was a driving force in the province’s economy. Today, many of the changes occurring in the farming community are impacting the unique rural character first established in the 19th century by British surveyors who laid out a grid pattern of concessions and side roads across the province. This grid created the framework for settlement and supported the efficient layout of 100- and 200-acre (40- and 80-hectare) mixed farms that remained the most prominent form of farming well into the mid-20th century.

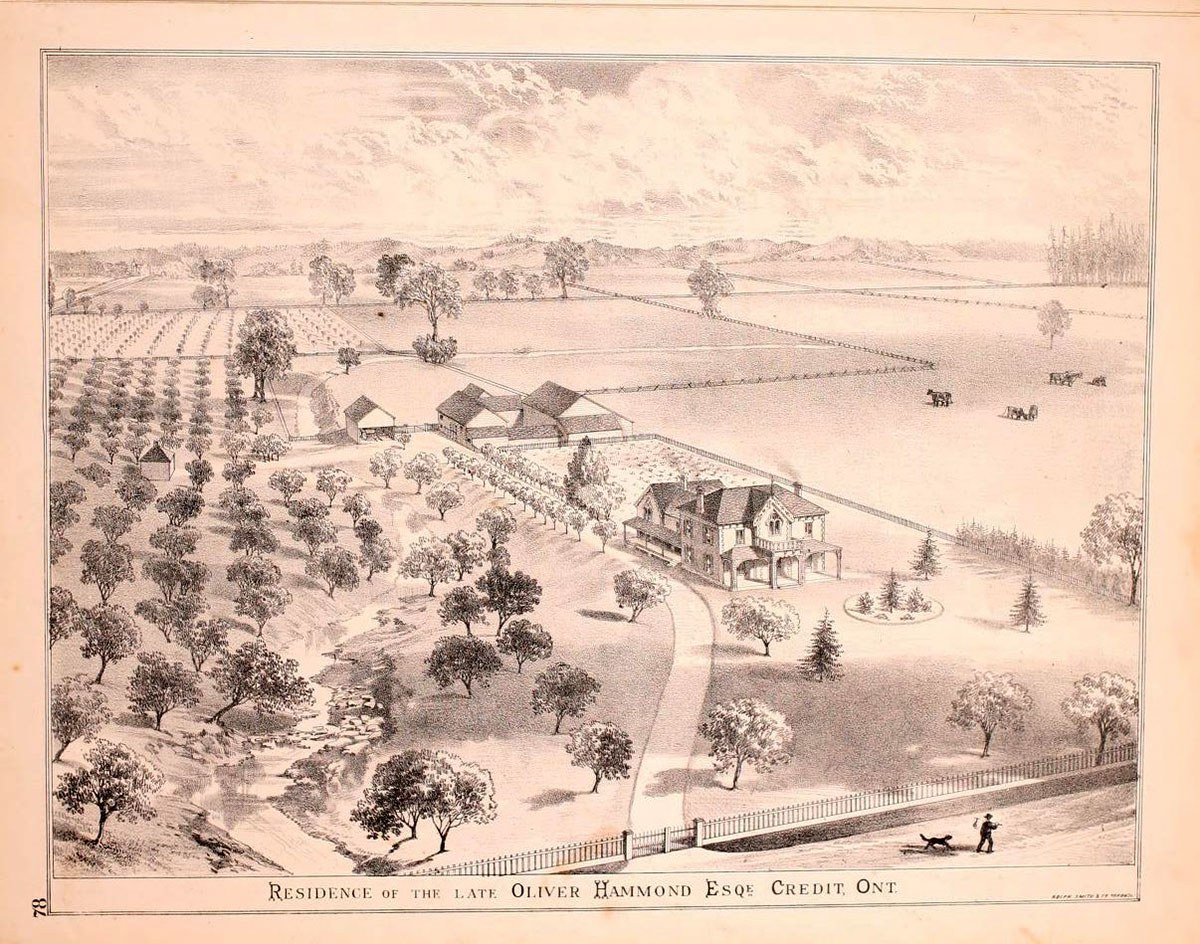

The mixed farm model was an extremely efficient organization of farm family labour, animal husbandry and crop production. It created a distinctive layout and division of the farm into eight to 10 fenced fields, a small managed woodlot for fuel and timber, a farmstead core dominated by a large timber barn for the farm animals and hay and grain storage, numerous outbuildings, and a spacious farmhouse surrounded by gardens and an orchard.

The division of the landscape into the domestic activities of the farm women and the production area of the farm men was guided by a well established layout pattern centred on the farm lane that linked the back fields and the farm core to the public road. Each of the fields was fenced to control the farm animals; trees and shrubs were allowed to grow along these fencerows, creating a well-defined border to each field. Within the farm core area, the farmer planted sugar maple and Norway spruce treelines to act as windbreaks and to define the boundary of the heart of the farm. Today, in many areas, these landmark treelines are the only remaining evidence of a former farm location.

This historical atlas sketch illustrates the ideal mixed farm layout. The farmhouse, barn and outbuildings are efficiently arranged along the laneway that links the fields and the farm core with the public road. (From the 1877 version of the Illustrated Historical Atlas of the County of Peel.)

Within the mixed farming environment, churches, cemeteries, schools and small enterprises created a community identity and local industry. For example, in the 1800s, there were 98 cheese factories operating in the countryside of Oxford County – close to the source of the milk and cream on which they depended.

The mixed farming economy improved in the early 20th century with the expansion of Niagara’s electric power into rural areas. This advance hastened the dramatic change in farm practices. As well, new efficiencies were gained by replacing horse power with tractors. As larger mechanized equipment became more effective, extra farmland was required to keep the farm profitable. As a result, by the mid-20th century, the size of farm holdings grew with the consolidation of multiple farms into single ownerships. As additional farms were acquired, many of their farm buildings and fencerows became redundant and were demolished. As farmers changed to large-scale cultivation of specialized crops – such as corn – the mixed farming pattern was all but erased.

Farmers have consistently been innovative in their farming practices, changing quickly to different crops and equipment in response to market conditions. This change has resulted in the constant evolution of the rural landscape caused by the nature of the agriculture industry itself.

Today, the rural landscape is also facing pressure for change from outside the farming community. New infrastructure installations – such as communications towers, transmission lines, solar panel stations and wind turbines – are adding large structures to the farming environment. Similarly, suburban development to the limits of our urban boundaries, and the expansion of employment areas on the edges of many small towns, have created land-use changes that alter the historic pattern of agricultural use and, in turn, create more demand for road improvements and services.

The traditional rural road had a narrow cross-section and was lined with naturalized vegetation and deliberately planted trees. In many areas, mature sugar maples still shade these back roads, adding to their appeal as scenic routes. These roadside edges, however, are vulnerable to road-widening improvements needed to accommodate increased traffic.

Despite these developments, glimpses of the historic pattern of agriculture still exist in some parts of the province. For example, the farmers in the Waterloo region are generating some of Ontario’s highest receipts despite a reliance on traditional horsepower on farms averaging 64 hectares (159 acres). Furthermore, throughout the province, a new generation of farmers is successfully experimenting with a range of new products and specialized crops for niche markets. This change is creating new patterns of farm buildings within the historic country road grid, the foundation of the agricultural landscape. This ongoing evolution of the landscape is clearly evident to any traveller who ventures off the highway to see what’s up at the farm.

![Rose Lieberman, Rose [Hanford?] Green and Aaron and Sarah Ladovsky in front of United Bakers restaurant, Spadina Ave., Toronto, 1920. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, fonds 83, file 9, item 16.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/SoupsOn_Archival_3505.jpg)