Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Protecting Ontario's agricultural landscapes: Challenges and opportunities

Cultural landscapes, Food

Published Date: Oct 12, 2012

Photo: Farmland along the Niagara Escarpment, near Milton (Photo: Ontario Tourism)

Agriculture is an integral part of Ontario’s story. It has shaped and impacted the growth and development of communities since the province began.

Although agriculture in 21st-century Ontario is subject to a number of pressures and challenges, it also presents exciting and innovative opportunities for social and economic prosperity, and for the preservation of significant working landscapes. One way to support the preservation of Ontario’s agricultural heritage is to build on past traditions to embrace new and creative approaches to farming in the province. Such approaches have the potential to ensure that agricultural land continues to be used for its intended purpose, and remains a viable part of Ontario’s identity, while supporting alternative options for building community, stimulating the economy and enhancing the development of a sustainable food system.

As demonstrated by the hot, dry conditions of this past summer, agriculture is subject to ongoing challenges, including drought and shifting market costs. Such conditions can make farming difficult as farmers struggle to make ends meet, and to ensure the ongoing viability of their land. In addition to these ongoing challenges, agriculture – and the preservation of agricultural land in Ontario – is subject to long-term pressures that can have serious and, at times, irreversible implications for the future of farming in the province.

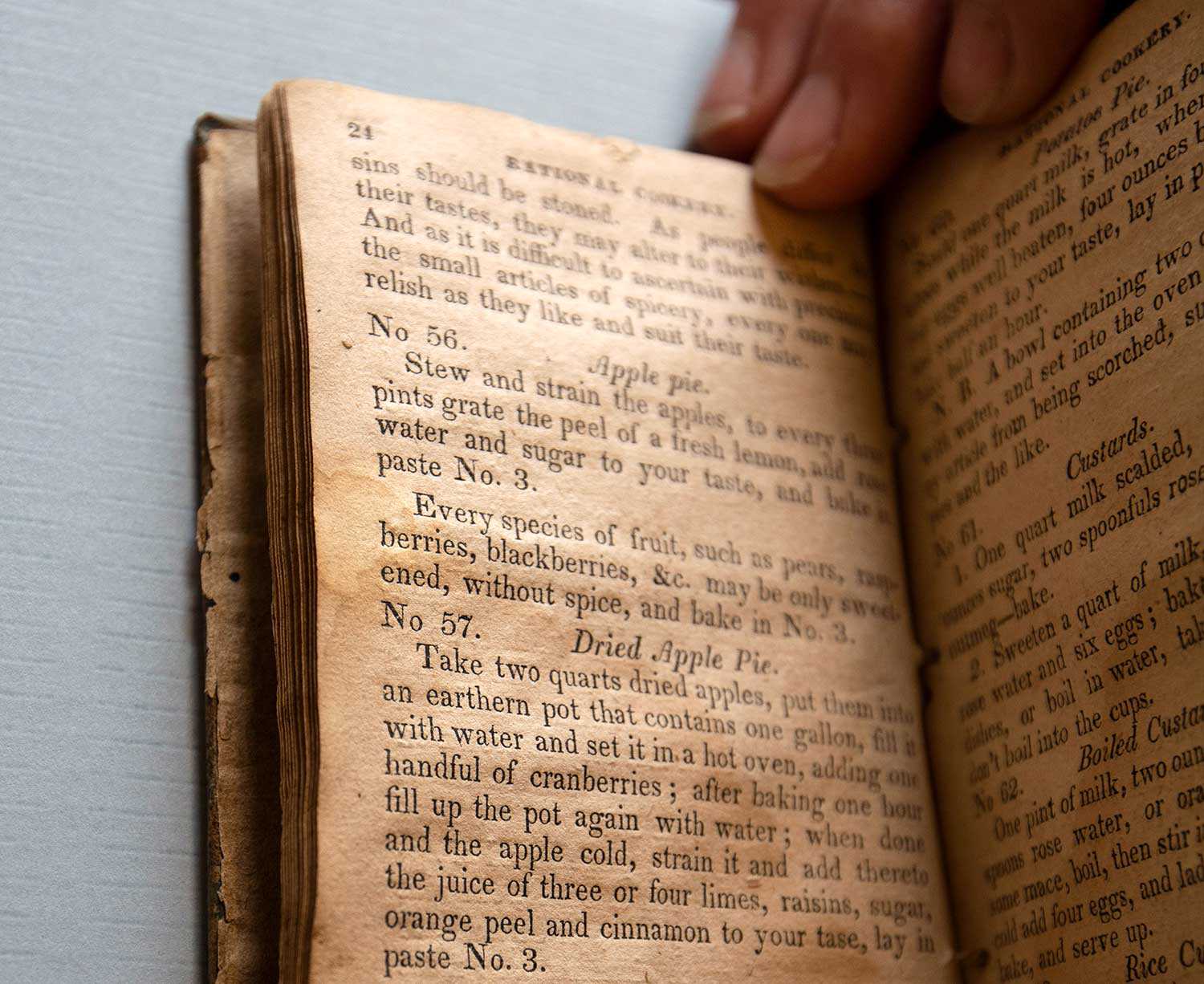

According to the Canada Land Inventory, only 0.5 per cent of the country’s land is categorized as Class 1 farmland. Over half of this land is located in Ontario, with some of the most fertile land located just west of Toronto. Ontario’s farmland, however, also represents an attractive, non-renewable commodity for developers who stand to benefit from urban and suburban expansion. Once this farmland is developed, it is lost forever. The 2011 Agricultural Census indicates a 9.2 per cent decrease in the number of census farms in Ontario between 2006 and 2011, and an overall 4.8 per cent decrease in farm area during this same period.

This disappearance of agricultural land is often accompanied by astronomical increases in the value of remaining farmland, particularly in proximity to urban centres. Although the land may be zoned for agriculture, it is increasingly purchased on speculation in anticipation of further expansion of the municipal settlement boundaries or future changes in current land-use planning restrictions. Such purchases can and do result in large increases to the value of nearby farmland, making it difficult for farmers who don’t wish to sell their land, and jeopardizing the long-term future of their agricultural enterprises

A related challenge arises from the loss of farmland biodiversity in Ontario due to the large and specialized nature of many of the province’s farms. In order to remain economically viable, many farms sell their produce to food companies that demand massive quantities of a uniform product. This agribusiness approach is focused on the production of crops that can be grown quickly and reliably, often at the expense of the survival of local and regional crop varieties, and of the overall ecological health of the land. Unfortunately, at present, few financial incentives exist to enable farmers to act as environmental stewards by pursuing an agricultural approach that embraces biodiversity and recognizes the place of farmland in the larger ecological system.

The future of agriculture in Ontario is threatened by a loss of farmland and by a shortage of current and future farmers. Our current generation of farmers is aging; statistics suggest that few of their children want to take over the family farm. This situation is compounded by the increasing costs of farming and the availability of cheap, imported produce, both of which make it difficult for Ontario farmers to remain competitive. And the high cost of good farmland is a barrier to attracting the next generations of farmers.

A drastic reduction in agricultural infrastructure – such as processing facilities, abattoirs, cheese plants and other related industries – has also altered Ontario’s agricultural landscape, as produce is now often shipped much farther afield for processing before being transported to destinations across the globe. It is estimated that only 10 to 15 per cent of the province’s overall food production actually makes it to Ontario tables, the rest being exported. This fact greatly limits access to ready and affordable local food options.

The challenges presented by current production systems, and competition from large retail outlets able to sell foreign-grown food at low prices, make it difficult for farmers to earn an income by selling directly to consumers. This distance between producer and consumer can contribute to a decline in knowledge about how food is produced, and about how to shop for and cook fresh food by taking a local, healthy and affordable approach.

In spite of these challenges, new and innovative approaches that support farming and the preservation of agricultural land across Ontario continue to emerge. For instance, the Ontario Farmland Trust (OFT) works directly with farmers through its Land Securement Program to ensure that their land is protected, and retains its potential for agricultural and conservation practices over the long term. The OFT also works to address the challenge of the often-prohibitive cost of farmland by leasing out parcels of its land, on a long-term and secure basis, to beginning farmers at rates they can afford.

Publicly owned land also offers opportunities for agriculture in both rural and near-urban areas. For instance, the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) rents over 3,000 acres (1,214 hectares) of its land for farming, and embraces an innovative vision for sustainable agriculture. Additionally, the newly emerging Rouge National Urban Park presents interesting possibilities for farmland preservation and the encouragement of small-scale and sustainable agricultural practices.

Movements to preserve and provide agricultural land to novice farmers are also accompanied by initiatives that encourage existing farmers to manage their land sustainably and to recognize their role as environmental stewards. One such volunteer initiative, the Canada-Ontario Environmental Farm Plan, works with farm amilies to identify environmental strengths and weaknesses, and to suggest specific actions and projects to improve environmental conditions on their farms. In addition, the Alternative Land Use Services (ALUS) program, which has been piloted in Norfolk County, pays farmers for stewardship activities that help to support biodiversity through the conservation and protection of natural features on the agricultural landscape, and that result in a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

Such initiatives are also accompanied by efforts to maintain the biodiversity of seeds and livestock in the face of a more industrial approach to agriculture – including genetically modified crops and domination by few varieties or breeds. Seeds of Diversity works to promote traditional knowledge of crops and garden plants through the preservation of heirloom seeds, while Rare Breeds Canada focuses its efforts on the preservation and survival of heritage livestock. Together with farmers from across Ontario, these organizations help to maintain biodiversity in the local food supply, and to help ensure that local seed varieties and livestock breeds remain a part of Ontario’s agricultural landscape.

The preservation of agricultural land and the promotion of sustainable and ecological farming practices speak to the need to engage and empower a new generation of farmers through education, training and mentorship. This new generation may include young people from farming and non-farming backgrounds, as well as immigrant farmers who bring considerable knowledge and skills that can be applied in an Ontario context. In recent years, a number of training programs have been initiated in Ontario by organizations such as FarmOn Alliance, FarmStart, Collaborative Regional Alliance for Farmer Training and Farmers Growing Farmers. Together, these organizations have worked to provide internship and training opportunities for new farmers across the province. The Sustainable Agriculture program at Fleming College also provides prospective farmers with an opportunity to gain essential knowledge and hands-on agricultural experience.

The protection and future of agriculture in Ontario is also dependent on an engaged population that recognizes the value of farmland – and of buying local, healthy food that is produced using ecologically sound farming practices. Throughout the province, opportunities abound for Ontarians to learn more about local food systems, and to support farmers through the purchase of local produce. Farmers’ markets present a wonderful opportunity for consumers to engage directly with farmers in the purchase of fresh, local food. Community Supported Agriculture programs allow consumers to invest directly in local farms by paying an up-front amount for a portion of the season’s harvest.

Livestock continues to be an important part of Ontario’s agricultural heritage, as seen here on this farm along the Bruce Peninsula. (Photo: Ontario Tourism)

Communities, organizations and businesses across the province are embracing agriculture as a means of boosting tourism and the local economy, and creating healthier places to live and work. Across Ontario, “Eat Local” and “Buy Fresh Buy Local” initiatives have been established, encouraging consumers to connect directly with local farmers. A number of regions and communities have developed maps and food guides to connect people with local farms and produce. The pick-your-own experience is one way in which Ontarians can support local farmers while enjoying fresh, local food. Chefs in restaurants across the province are also working with local producers to bring fresh, healthy food to the table. As well, the provincial government has provided support for local food initiatives through the Ontario Market Investment Fund.

“The farm-to-table movement has to go beyond being trendy. As much as I have an ethical investment in buying from local and sustainable practices, my first commitment is to make delicious food that has value for my customers. What you quickly come to realize when you aim to source the best product is that the most delicious beef, the best tomatoes, the most flavourful trout, will undoubtedly come from farmers that practice heritage agriculture. Then it’s simply a matter of finding the farmers that are closest to you, as freshness is a major factor in quality and taste. The farm-to-table approach makes for better food. And that’s something everyone can get behind.” Carl Heinrich is co-owner of Toronto’s Richmond Station and winner of this year’s Top Chef Canada. He buys seasonal product from local farmers and brings in whole animals to butcher in-house. For more information on Heinrich’s new restaurant, visit www.richmondstation.ca.

Recognition of the need to reach out to young people to educate them about food and healthy eating drives a number of projects and initiatives in Ontario. For example, FoodShare Toronto offers innovative opportunities for students to learn about the local food system, and for fresh produce to be incorporated into school food programs. Students at Trent University support local food initiatives through on-campus organic gardens and the student-run café, The Seasoned Spoon. Additionally, a growing number of hospitals and similar institutions are providing fresh, local food.

While agriculture in Ontario faces many challenges, exciting opportunities also exist to ensure its place in the future of the province. The preservation of agricultural heritage is linked to these opportunities for creativity and innovation, which support working landscapes, embrace biodiversity and recognize the role of farmland and farmers in Ontario’s ecological and economic systems. By seizing these opportunities, Ontarians are helping to build a sustainable food system so that agriculture remains an important aspect of the province’s identity.

![Rose Lieberman, Rose [Hanford?] Green and Aaron and Sarah Ladovsky in front of United Bakers restaurant, Spadina Ave., Toronto, 1920. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, fonds 83, file 9, item 16.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/SoupsOn_Archival_3505.jpg)