Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Preserving the Huronia Regional Centre

Expanding the narrative

Published Date: Sep 07, 2018

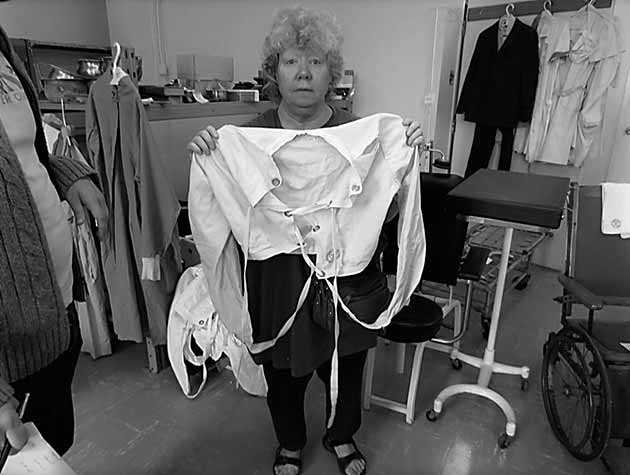

Photo: Huronia class-action lawsuit lead plaintiff Pat Seth displaying a strait jacket used at the institution. (Photo: Nancy Viva Davis)

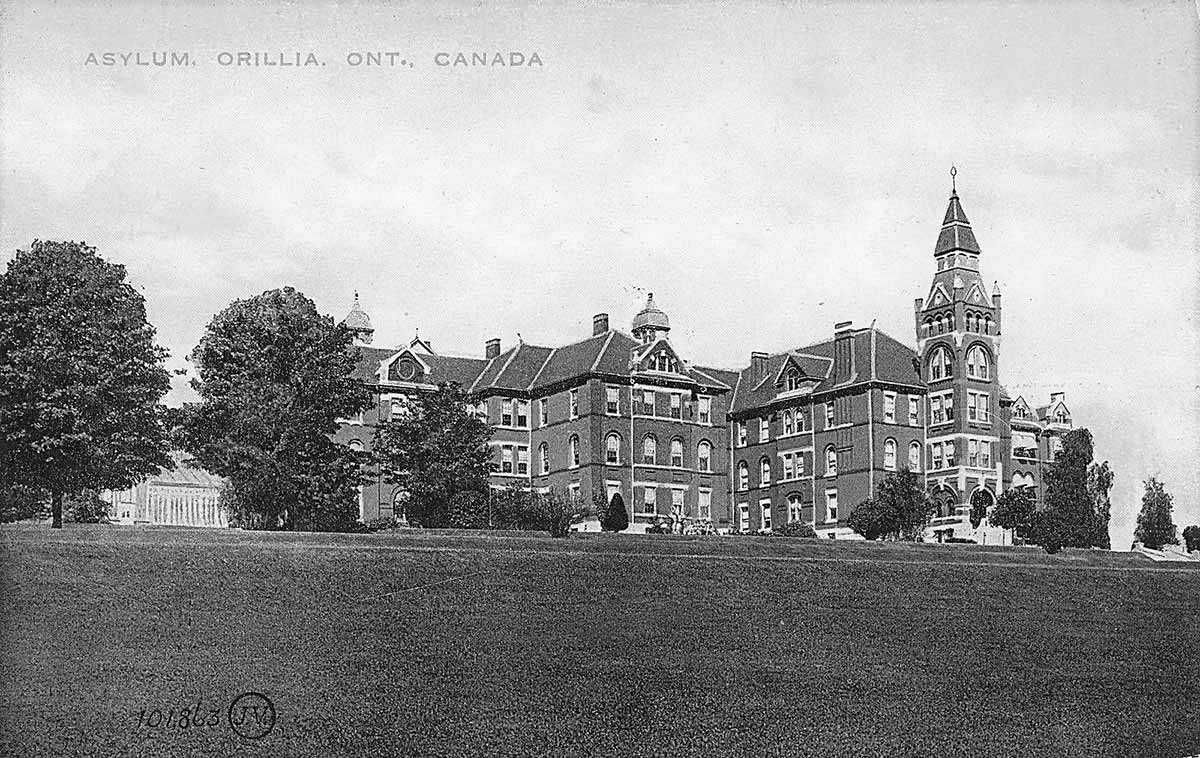

Along the shores of Lake Simcoe, the rolling hills of Ontario farm country slopes gently towards the water. Here, city dwellers flock to escape the heat and bustle of urban life. The waterfront is dotted with cottages and rentals for just such purposes, and the quaint, often-sleepy town of Orillia sits at the head of the lake, welcoming visitors and residents alike. But this picturesque scene belies a darker history of this area. On the shores of Lake Simcoe, just outside Orillia, sits the corpse of the Huronia Regional Centre: a now-shuttered institution designed to warehouse people diagnosed with intellectual disabilities, whose history includes the deep neglect of, and in many cases, profound and sustained physical, sexual and emotional violence against those incarcerated within.

The Orillia Asylum for Idiots opened its doors in 1876. The asylum, later renamed the Orillia Hospital School and later still the Huronia Regional Centre, fell under the auspices of the Government of Ontario, whose Mental Retardation Policy sought to contain and isolate people identified as “retarded,” both for their own benefit and for that of the broader society. The goals of this policy later dovetailed with Canada’s eugenics movement, which supported the institutionalization and forced sterilization of the mentally ill. This institution remained open until 2009, and during this time contained thousands of Ontarians. Heartbreakingly, the legacy of this institution is one that has remained largely outside the public purview, and has therefore not generated the kind of public outrage and attention it deserves. Many people lived, suffered and died at Huronia, taking their stories of abuse to the grave.

In 2012, I became aware that a large class action lawsuit was being launched against the Ontario Government on behalf of Huronia survivors. As a researcher, I am interested in using storytelling to gather and preserve important social experiences. Because of this, I reached out to Jim and Marilyn Dolmage, the litigation guardians for the lawsuit’s two lead plaintiffs, Marie Slark and Patricia Seth. They were eager for help. Through the process of the lawsuit, launched in 2010, all four of them recognized how many untold, unheard stories there were from Huronia, and were desperate that these living legacies not be ignored or forgotten further. We all agreed. This dark part of Ontario’s recent past must be preserved so that we do not repeat the same grievous errors in the future.

Together, we began to assemble a team of Huronia survivors, researchers and allies interested in collecting such stories. The court case settled in 2013 and, in 2014, our group made our first collective action together by revisiting the Huronia site (now closed to the public permanently). For those of us who did not experience life at Huronia, this was an overwhelming experience. Our survivorcolleagues led the way through the dark, broken halls of the institution, pointing out where they had been held in solitary confinement for long periods of time, where they had been beaten, raped, made to hurt one another, overmedicated, underfed and exposed to a grotesque litany of punishments. We held hands in the cemetery and sang together, remembering and paying tribute to all those who did not leave the institution alive, and now resided somewhere under a jumbled mess of numbered gravestones.

Over the years, we came collectively to piece together a picture of life at Huronia that had not been drawn before. With survivors leading the way, we worked to understand dynamics between staff and patients, the ubiquity of violence, and the unceasing demands of the institution for free labour, behavioural compliance and deep social isolation and neglect. This has helped us enormously in the task of trying to understand how and why institutional violence happens with such regularity. This was, however, incredibly hard work. The survivors involved in this project were unceasingly generous with their time, their expertise and their willingness to expose the brutality that they endured, even when this came at the cost of their own emotional equilibrium. Further, not everyone had the same stories: each person’s experience of incarceration was unique, although many overlaps emerged. For those of us receiving the stories, it was hard not to feel undone by what we learned. Often, we were the first people to have heard these stories, and this was a task that felt both vital and fraught.

Our team has worked over the past several years to find ways of communicating the legacy of Huronia lest it be forgotten. We have held a cabaret, written articles and a book, and are working on an online legacy project. One of the most important ways that this has occurred, however, is through the creation of the Huronia Speakers Bureau (www.huroniaspeakersbureau.ca). The Speakers Bureau is an organization of survivors who are willing to speak publicly about their time incarcerated. This work is particularly important as it gives the opportunity for members of the public to hear the complicated, difficult stories of life at Huronia from those who lived these experiences directly. While the Speakers Bureau certainly does not heal the old, deep wounds of trauma, offering survivors the chance to tell their experiences benefits us all.

A settlement agreement reached in a class-action lawsuit brought against Ontario by former residents of Huronia Regional Centre was approved in Superior Court on December 3, 2013.