Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Perspectives on the War of 1812

A British perspective, by The Honourable David C. Onley

2012 promises to be an extraordinary year for all Canadians. We will mark both the bicentennial of the War of 1812 and the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty The Queen. These two events highlight the core values that have defined us as a people.

Two hundred years ago, we took up arms to ensure that we would be governed according to British parliamentary, not republican, concepts. Two centuries later, our former foe is a strong ally. As a fully independent nation, we celebrate the 60th year of our sovereign’s reign.

Canadian history has witnessed the search for common virtues among distinct peoples. While we have often disagreed, Canadians have always been prompt to defend our shared values in the face of threats from near and far. All the while, the Crown has played an integral role in safeguarding our democratic process.

The response by Canadians to the American challenge of 1812 showed that Aboriginals, francophones and anglophones would defend those common values and loyalties to the Crown. While Confederation would not occur for another 55 years, the unique Canadian sense of duty and love for this land had already been born in battle and through bloodshed. What we have become today was begun long ago.

As Lieutenant Governor, I have witnessed first-hand that sense of duty right across our diverse province. It is a great privilege to recognize countless volunteers whose time and dedication to our communities make for a quality of life second to none.

Our deeply ingrained values, nurtured through the centuries, allow for more than just the promotion of tolerance, but also for the understanding and acceptance of difference. This spirit yields immediate benefits to us all and is of increasing relevance in an ever-more-diverse and interconnected world.

When the War of 1812 ended, no territory had changed hands and no government was overthrown. For Canadians, the results would set in motion the path to nationhood. We would remain loyal to the Crown, yet become a truly independent nation.

Today, we pursue our own role on the world stage, while at the same time, as a proud member of the Commonwealth of Nations, we celebrate our monarch’s 60th anniversary.

Equally, during this bicentennial year, we celebrate that the Canadian-American border – the longest in the world – remains demilitarized. It is an example to the world that old enemies can become fast friends and that differences can be resolved peacefully.

An American perspective, by Martin O'Malley

The vote by the American Congress to declare war against Great Britain in 1812 was its closest war vote ever. Maryland’s representatives – and Marylanders in general – were just as divided.

Sea trade-dependent Marylanders perhaps felt more than most Americans the sting of one of the war’s precipitating causes – the impressment of American sailors by the Royal Navy – more than 10,000 by the start of the war. Two Marylanders were notoriously impressed in 1807 from the USS Chesapeake – the memories of which simmered throughout the war and became that generation’s Boston Massacre.

Once war was declared, Maryland witnessed its first fatality in July 1812 during the Baltimore riots between pro- and anti-war factions. Passions ran high in Maryland and the Chesapeake area throughout the war.

Although fighting between Americans and the British did not begin in the Chesapeake until spring 1813, Maryland became the stage for more military actions than any other state during the next 18 months in a period that has been called “Terror on the Chesapeake.” The improbably successful defence against the British Army and Navy at Baltimore in September 1814 – just two and a half weeks after the burning of the President’s House and Capitol – was pivotal in bringing an end to the war. The defence of Baltimore was comprised largely of militia – citizen soldiers – and consisted largely of non-American-born and free and enslaved African-Americans.

The Battle of Baltimore gave America two of its most important icons – the Star-Spangled Banner flag (today, the most sought-out object in the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.) and its anthem. It also contributed to a new sense of American identity in the process.

War left Maryland devastated. It is estimated that 4,000 enslaved individuals and their families – important human capital in the state’s economy – left with the British for settlement in Nova Scotia, Trinidad and elsewhere. Those resettled communities survive today in places like Halifax. The southern Maryland region especially was left burned and devastated, not to recover until the 20th century. Rich Baltimore merchants had sunk their merchant fleet to protect the harbor. But the inspiration taken from the successful defence against the British – from the instant of “the dawn’s early light” – gave rise to a collective and immediate impulse to commemorate those events that have lived on through two centuries. Defenders Day is Maryland’s oldest holiday.

Reasonable people will debate for centuries to come the causes and outcomes of the War of 1812. Perspectives will vary by region and nation – but ultimately our shared passion about the War of 1812 is about our love of place, the celebration of unity in our diversity and survival in the face of adversity.

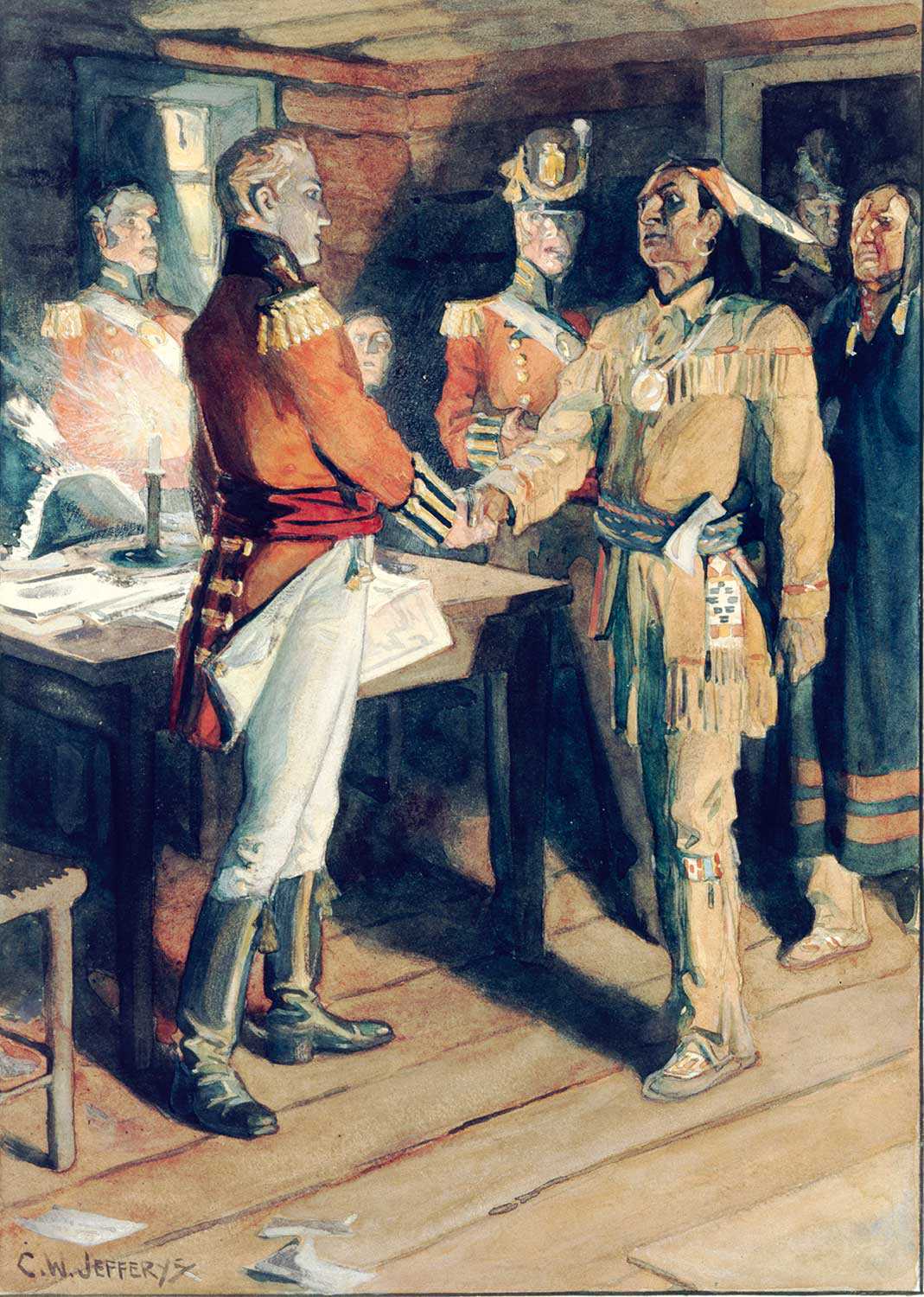

A First Nations perspective, by Harvey McCue

What was the role of First Nations? First Nations served as strategic and vital allies, more so in support of the British than the Americans. Britain desperately needed the additional resources offered by the First Nations as both defenders and combatants. Both sides acknowledged the effectiveness of First Nations’ military strategies and First Nations warriors earned the distinction of fierce combatants as a result of their resistance to aggressive encroachment on their traditional lands.

Who were the participating First Nations? Numerous First Nations contributed to the war on both sides. For Britain, the most celebrated participants included Tecumseh, a significant leader of the Shawnee nation, and his half-brother, the Prophet, Tenskwatawa. They forged a temporary confederacy of First Nation warriors from the Wyandot, Pottawatomie, Ojibway, Ottawa (Odawa), Creek, Winnebago and Kickapoo nations, and their own Shawnee supporters.

The Iroquois confederacy (the Six Nations) were initially neutral, but eventually entered the war supporting both sides. They included warriors from the Grand River under John Norton and John Brant and the Bay of Quinte as well as members from St. Regis, and Kahnawake and Kanesetake in Lower Canada.

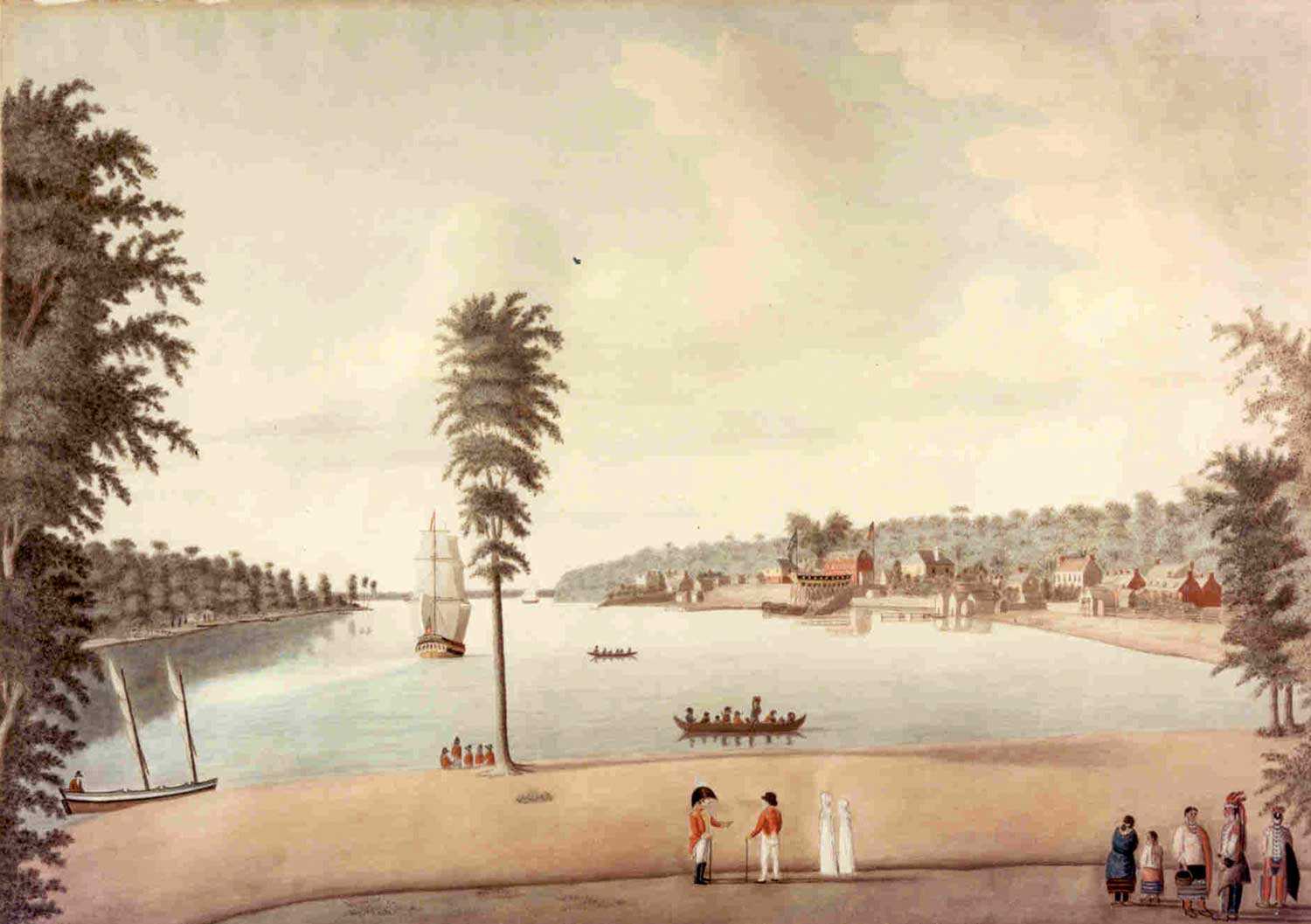

Mississauga and Ojibway warriors from lakes Simcoe, Couchiching, Muskoka and Rice led by Yellowhead, Snake, Assaince and Mesquakie defended Fort York and fought alongside warriors led by Odawa and Ojibway leaders, Assiginack and Shingwaukonse.

Supporters of the American military included warriors from the Choctaw and Creek nations. Six Nation warriors from the Seneca, Onondaga, Oneida and Tuscarora nations, many residing on the Alleghany, Cattaraugus, and Cornplanter reservations in present-day New York, allied with the Americans.

Why did they fight? For Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, the war offered another opportunity to defend their traditional lands in present-day Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Michigan from increasing American encroachment, a campaign begun in earnest in 1763 under the Odawa leader Pontiac and carried on in 1791 by Tecumseh’s predecessor, the Shawnee leader, Blue Jacket and his Miami ally, Michikinikwa.

In reality, Tecumseh’s 1812 confederacy was the last gasp for First Nations in North America to protect a vast traditional territory unencumbered by a foreign presence.

For the British-leaning Iroquois, the War of 1812 enabled them to retaliate for the American razing of their communities in New York – a campaign that began in 1779 and continued after the American War of Independence. It also renewed their allegiance to the British crown, an allegiance with roots in the Seven Years War and the Proclamation of 1763.

For the Mississauga, Ojibway and Odawa warriors and leaders, such as Assiginack (Blackbird) and Shigwaukonse (Little Pine) of Upper Canada, their war effort fulfilled their loyalty to the Crown.

Without First Nations support in many key conflicts during the war, Ontario would not exist today. First Nation leaders and warriors fought decisive battles at Queenston Heights, Beaver Dams, Stoney Creek and the retaking of Fort George.

A Canadian perspective, by Charles Pachter

Commemorating military anniversaries – in this case a war that took place 200 years ago – can be problematic. Faded memories and revisionist histories often gloss over the grim realities of long-past conflicts.

The War of 1812-15 can be seen as the American Revolutionary War, Part Two. This round focused on the plucky new American nation of 18 states looking to expand into British colonial and Native-held territories. Many people thought the defeat of Britain would be easy, given that they were distracted by war in Europe. At the time, the British Canadian colonies of Upper and Lower Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick had perhaps 75,000 inhabitants, compared to the burgeoning American population of 8 million.

But victory was not as easy as some thought. The war, fought mainly on now-Canadian soil, was full of grim and grisly reality. You wouldn’t think that if you went by how today’s battle re-enactors portray soldiers from 200 years ago. At any given historic site, most of the emphasis is on crisp uniforms, polished rifles and boots, immaculate white triangular tents – more on what they wore than on the suffering and horrors of battle.

The suffering and horrors were real. Soldiers were as likely to succumb to sickness and disease as to battle wounds. Amid the mosquitoes and malaria, the battles were punctuated by blundering, plundering, pilfering and pillaging, as well as scalping and eviscerating, and the amputation of limbs. Not to mention simple starvation. From the pioneer settler’s perspective, the atrocities of war included the destruction of private property, stealing of livestock, burning of barns and homes, pilfering of grain, vegetables and clothing.

When it was all over, not one inch of territory got exchanged. Two emerging nations – white tribal cousins, many former compatriots, attacking and defending – killed one another for power and turf. The real losers, of course, were the First Nations peoples.

Once the British victory over Napoleon occurred, thousands of seasoned soldiers arrived in the British North American colonies. Who knows how differently things might have turned out if the defeat of Napoleon hadn’t happened? Would Upper Canada, now Ontario, have become a huge American state?

Much will be made in the coming months of this conflict that finally put an end to the fighting between two restive neighbouring nations in the making. And, lest we forget, the senseless sacrifices of so many led eventually to the peaceful co-existence that we now take for granted between our two great democracies in the 21st century. May that peace continue.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)