Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Sport matters: The value of sport to society

No account of Ontario’s heritage would be complete without some understanding of the ways in which Ontarians have engaged in sport. In every time period – from the aboriginal millennia before the European arrivals, through the fur trade, the first agricultural settlements, urbanization and industrialization to the information-driven city/regions of today – the peoples who have lived here have given purpose, excitement and meaning to their lives through physical tests of strength and sports.

Each of these societies has given its own particular character to sports. In the 19th century, for example, when most people had to walk to get anywhere, huge crowds watched the professional sport of pedestrianism or “go as you please,” in which athletes walked and ran long distances, sometimes days at a time. The early railroads, which enabled teams to travel great distances (and which ran on the newly established standardized time), as well as mass production, which gave us standardized equipment, gradually led communities to adopt the same rules. Before that time, every town had its own unique way of playing.

Just as they were shaped by these economic and social changes, sports also contributed to them. The fascination of sports spurred passenger (and later automobile and plane) traffic, technological innovation, urban investment and advances in communication. The spread of sports has been inextricably linked with the development of Ontario society.

“Volleyball” c. 1914. P013, Accession 1991-01-258. Photo courtesy of the City of Thunder Bay Archives.

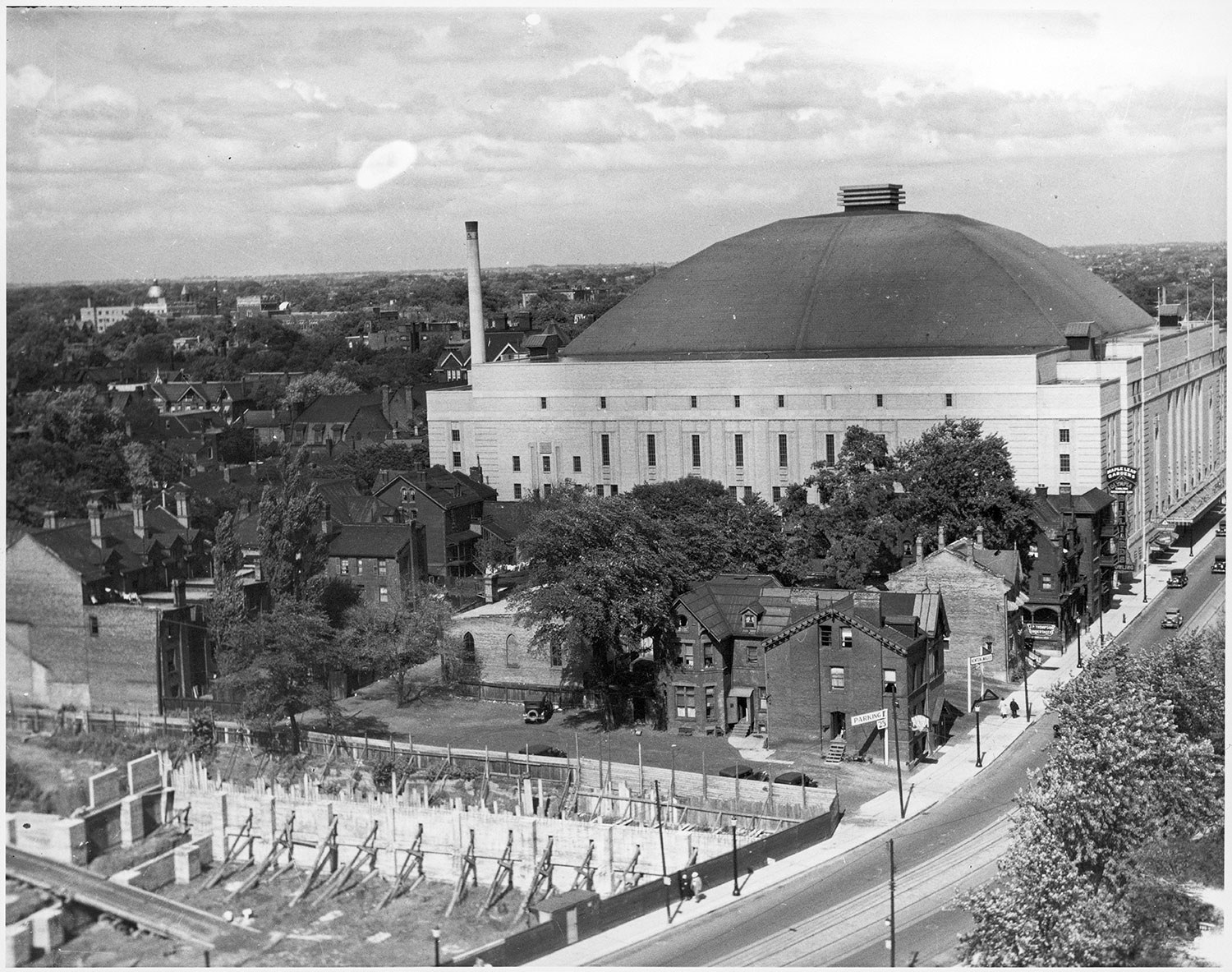

Today, in many Ontario households and communities, the calendar of life revolves around school, work and sports. Celebrated teams give pride of place and economic stimulus. Arenas and stadia provide key landmarks, draw larger congregations than places of worship, and bring people together across the divides of class, culture and religion in a common devotion to the home team. Many of the best facilities commemorate formative episodes in our history, such as First and Second World War memorial arenas that dot the landscape, or the recreation centres built to celebrate Canada’s centennial. I have never been to a local history museum that did not have some artifact or display on sports.

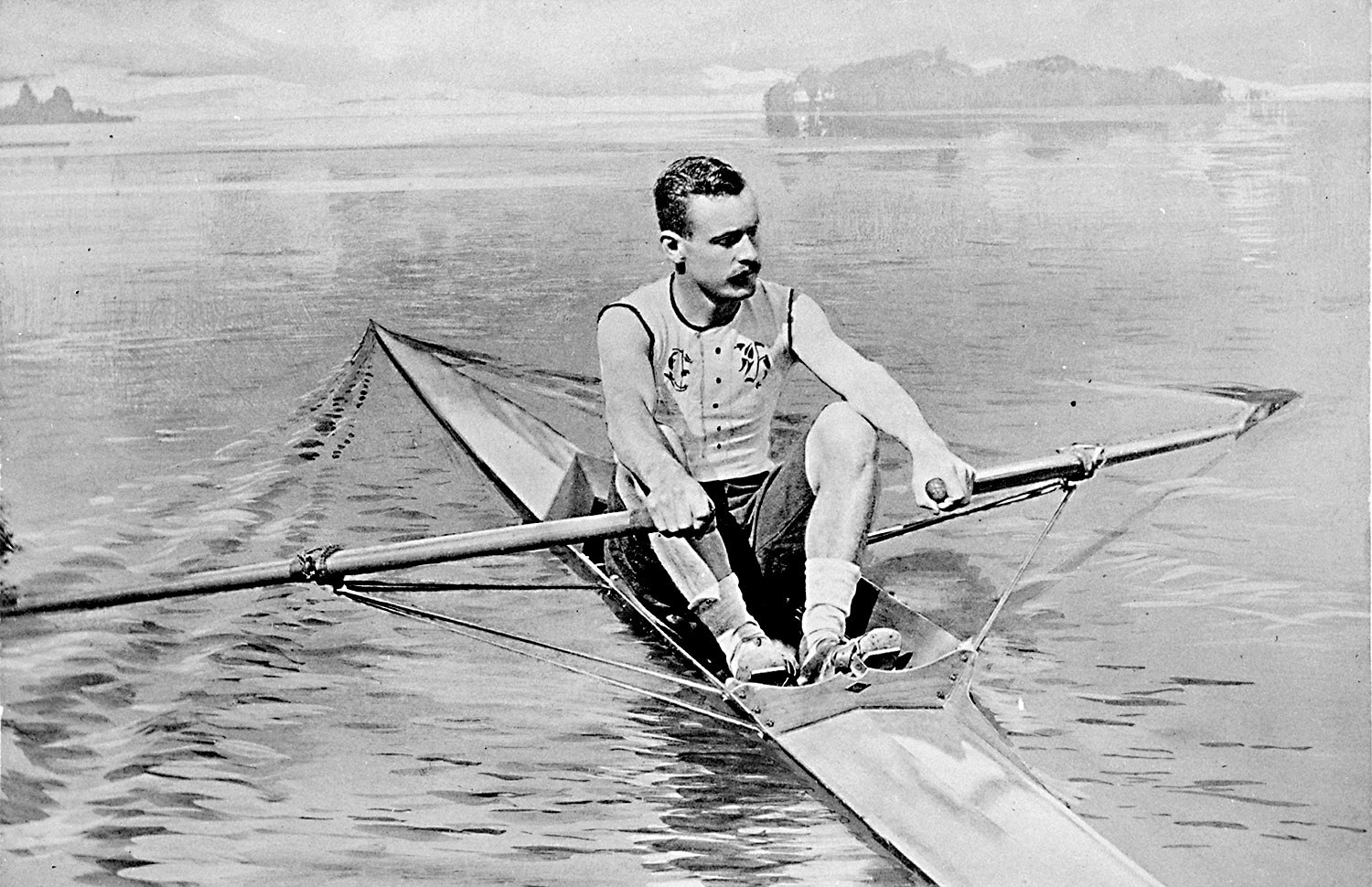

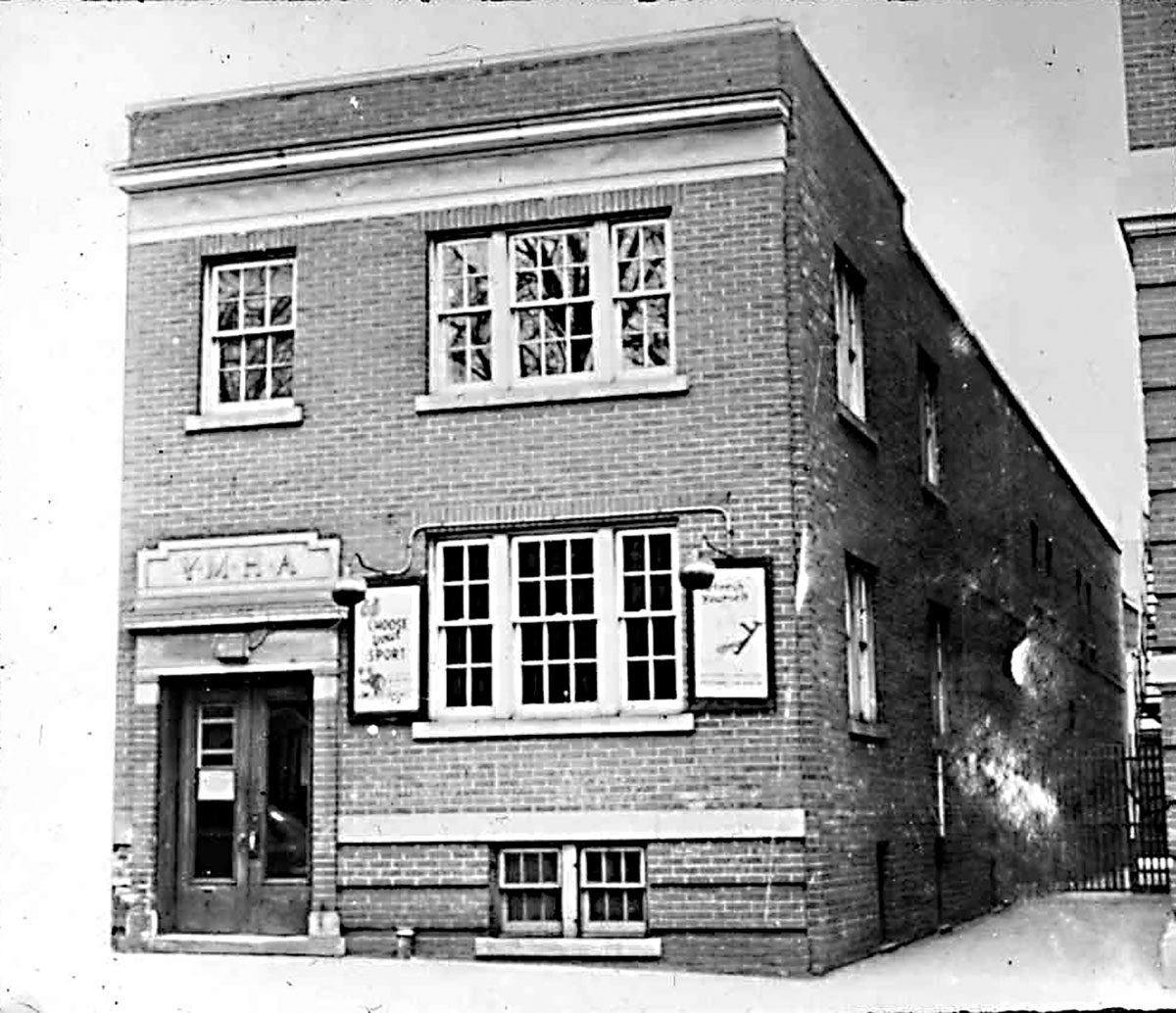

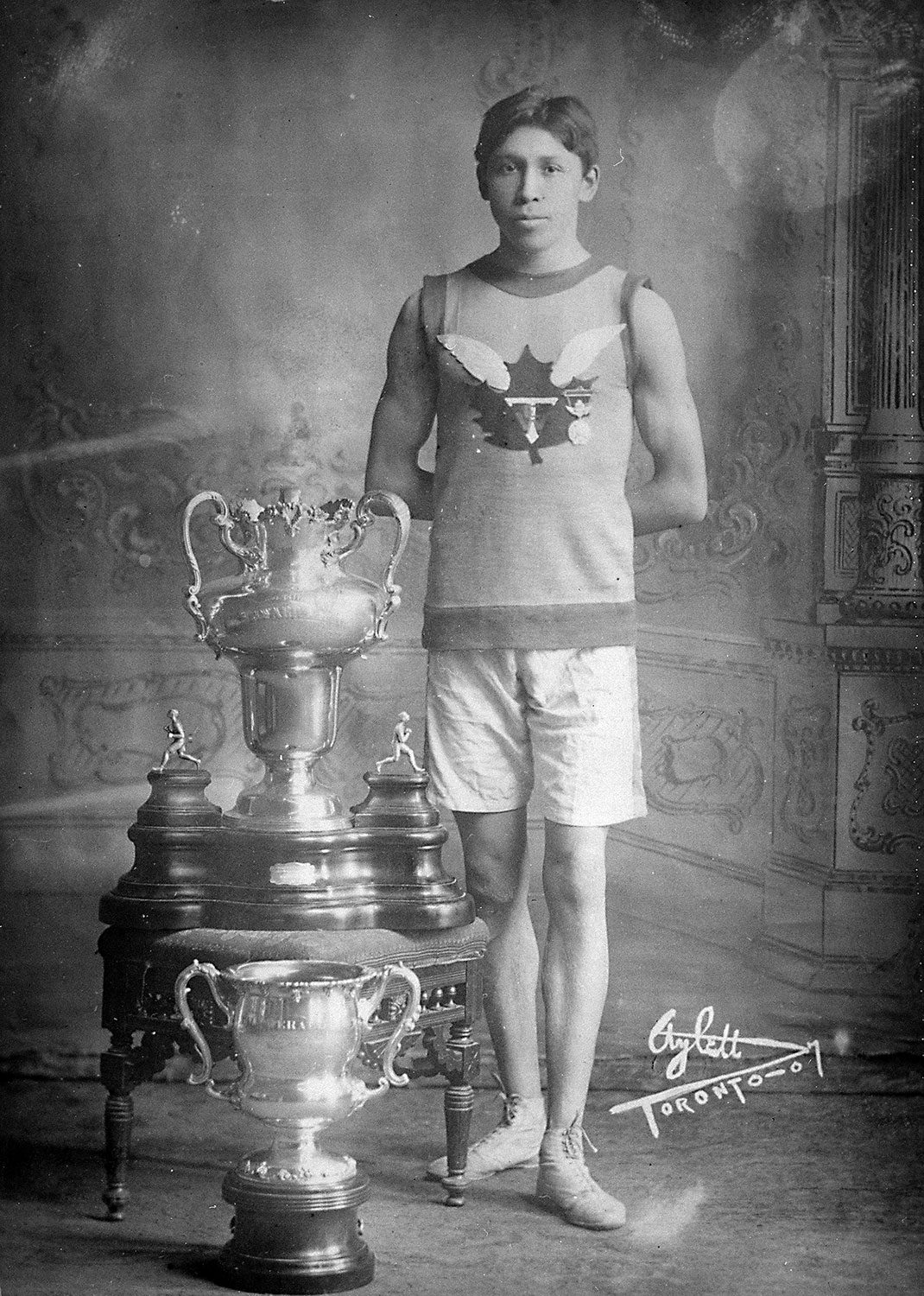

Of course, the best stories about Ontario sport revolve around the athletes and teams who have played here, enriching our lives with their heroics and travails, and affording us lessons about the human experience long afterwards. In the 19th century, it was rower Ned Hanlan – who won and held the world’s professional singles championship for five years against much larger Americans, Britons and Australians – who first gave Toronto and Ontario international renown rivalling that of the larger and more-established Montreal. Early in the 20th century, the remarkable Onondaga marathon runner Tom Longboat enhanced that reputation. When he won the Boston Marathon in 1907, running for the West End YMCA in Toronto, city controller William Hubbard said that “I don’t know anyone who has done more to help the Commissioner of Industries than this man Longboat.”

Every generation makes role models out of its favourite athletes. When I was growing up in the 1950s, a number of the young women in my neighborhood were named Barbara in hopes that they would grow up with the same artistry and determination as the Ottawa figure skater and Olympic champion, Barbara Ann Scott. Although he has not lived in Parry Sound since he was a teenager, Bobby Orr’s name lives on in town with two buildings named after the outstanding hockey player: a multi-purpose community centre and a hockey hall of fame. Many cities, towns and regions have their own sports halls of fame. It is not only Stanley Cup-starved Toronto that lives and dies by the fortunes of its signature teams. It happens every weekend in every town across Canada.

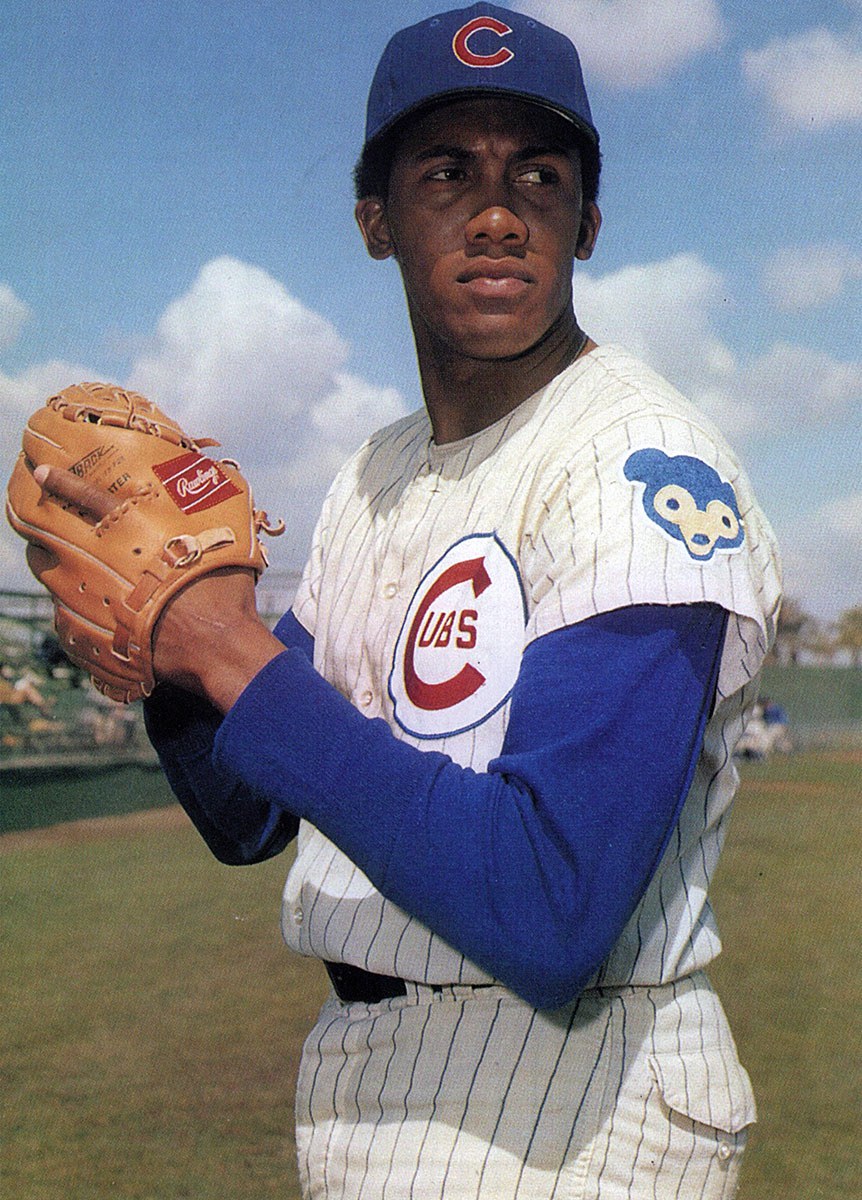

But not everyone has had equal access to sports in Ontario. Sports were initially developed, played and celebrated as part of men’s culture, with girls and women kept to the sidelines. Well into the 20th century, members of First Nations, Blacks, non-British immigrants and the working class were also excluded or discouraged – by explicit prohibition, prejudice or economic hardship.

One of the most inspiring narratives of Ontario sport is the way in which those excluded fought to win opportunities for themselves, while progressives helped them. At first, those excluded held their own events and formed their own clubs and organizations. During the first wave of feminism, women did this under the slogan “Girls’ sports run by girls,” creating their own clubs, provincial and national organizations and competing in their own Olympics. The Ladies’ Golf Club of Toronto, established in 1924 by Ada Mackenzie in Thornhill, is a remnant of this effort. It is the only surviving women’s-only club in North America.

Virtually every immigrant group, as soon as it developed a critical mass, did the same. For much of the 20th century, for example, Finnish Canadians – whether in mining or lumber camps in northern and northwestern Ontario or in large cities such as Thunder Bay, Sudbury or Toronto – ran ambitious programs and brought everyone together every summer for a provincewide gymnastics festival. In the 21st century, Asian immigrants did the same with kabaddi, sepak takraw and Chinese volleyball. Sometimes, the skill and élan of outstanding athletes from marginalized groups helped them overcome prejudice, enter the mainstream and legitimize their entire group. One such story is that of Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld, after whom the annual Canadian female athlete of the year trophy is named. In the early 1920s, Rosenfeld was a poor, Russian, Jewish immigrant living in Barrie before her accomplishments in ice hockey, softball and track and field took her to Toronto and ultimately an influential journalism career at The Globe and Mail.

While these struggles for equity in Ontario sport – and in society generally – continue to this day, they have been significantly aided by the creation of municipal and provincial facilities and programs. Human rights legislation also set higher standards for inclusion. In the 1920s, the Ontario Athletic Commission taxed professional sport to fund learn-to-swim programs in schools, subsidize amateur sports and build Canada’s first high-performance sport training centre (near Longford Mills – it is still used today as the Ontario Educational Leadership Centre). Ontario was the first government in Canada to fund amateur sports in a systematic way. Today, the Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport continues that tradition, enabling Ontario’s best amateur athletes to reach the highest levels of competition, while the Ontario Human Rights Code protects against gender, racial or religious discrimination.

Among the long list of Ontario’s contributions to sport and society is the strategy of using major games to drive urban redevelopment, capital expansion and community development through sport. In the late 1920s, a group of Hamilton sports leaders led by M.M. Robinson felt that they needed another cycle of international games to keep interest in amateur sport high during the four years between Olympic Games, and that such an event could strengthen community-building in host cities and regions. As a result of their efforts, they staged the British Empire Games in Hamilton in 1930. Despite the onset of the Depression, those games were so successful that, except for a hiatus during the Second World War, they continue to this day – now known as the Commonwealth Games.

In the decades since, many Canadian cities have benefited from the investment and excitement that the Olympic, Commonwealth and Pan American Games have generated, and Canada has earned an international reputation for successfully staging them. But except for the Canada and Ontario Games, which pursue the same strategy, Ontario has never hosted another one. Until this year.

The TORONTO 2015 Pan Am/Parapan Am Games, exemplify the strategy of capacity-building through sports, with major new and upgraded infrastructure and facilities across the entire Greater Toronto Area and beyond (from Welland to Oshawa), the training of volunteers and local financial contributions to maximize the commitment to lasting legacies. I am confident that these Games will inspire new and moving narratives about human capacities, while making a significant, positive impact on the quality of life in the region. In doing so, they will further enrich the value of sport to Ontario society.