Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Stick handling: The evolution of an icon

It has been written that culture is geography. In the case of Ontario’s reign as king of the wooden hockey stick, the geography of the Great Lakes basin gifted the area with the great natural resources needed to dominate an industry. Abundant, adaptable and durable, the trees that made Hespeler, St. Marys and Wallaceburg into legend were favoured by the climate and culture.

There was a time, shortly after the Wisconsonian Ice Age withdrew from the shores of the Great Lakes, that a squirrel could, if it chose, go from Georgian Bay to Georgia on the branches of white ash trees and never touch the ground. The rich soil left when the ice retreated was fertile ground for the abundant forests that built Ontario in its pioneer days.

Those stands of ash, elm, maple and other hardwoods provided the houses, the wagons, the furniture and the fuel for European settlers who arrived in the new world. In central and southwestern Ontario, forests were cut down and reworked into the stuff of everyday life.

Catherine Parr Trail, who wrote of life in 19th-century Ontario, was an English bride arriving in 1833 to the sight of “a sawmill … heaps of newly sawn boards, and all the debris of bark and chips, and skeleton frames of unfinished buildings scattered over the rough ground.”

Many small communities bearing evidence of their origins – London, Berlin, Dresden, Paris, Exeter, Culloden, New Hamburg – were nourished by the forest, creating a new culture. Part of that culture was a fast, frozen game to accompany the long winter months that shrouded the area. Born of First Nations and European games, hockey became the favoured sport of folks from Windsor through Toronto and over to the Quebec border.

The tools of the game were a rubber disc, ice skates and a wooden stick fashioned on the Irish hurley. In its earliest forms, the stick was usually hand-carved from a bolt of wood, often by aboriginals. Rock elm or hornbeam were the favoured woods, but, as it took longer to regrow them, the more prolific white ash soon became the preferred wood.

How early the first sticks appeared is a matter of some controversy. In 1851, farmer Alex Rutherford settled his family in Fenelon Township. He carved what appeared to be a hockey stick from the hickory found in the area. Over a century later, his ancestor Gord Sharpe found the gnarled stick in the cellar of the farm house. It is believed by some to be the oldest hockey stick in existence.

As the population playing the game flourished, artisan sticks could not keep up with the demand. With factories already turning out furniture, wheels, toys and coffins for the growing population, the elements were in place to mass produce wooden sticks in a factory setting. Saws were adapted to cut the timber into pallets. Huge presses employed for making pianos were adapted to bend those pallets into the familiar shape of a hockey stick. Ovens used to cure wood for axels and tresses were used to dry the green wood and make sticks more durable.

Here, Ontario was uniquely blessed by its geography. Hardwoods such as white ash, elm, alder, maple and hickory grew in many places in North America and in Europe. But the climate of the Great Lakes basin gave Ontario’s trees unique properties. The weather was cold enough to provide the lignin for stiffness and durability needed for a rough game. But the warm summers gave the wood the cellulose for flexibility that a great stick also demanded. Too far south in America, the wood was too soft. Too far north (or in Russia) and the wood was too stiff. Ontario’s wood was just right.

By the 1920s, every town with a river, a mill and hockey players seemingly turned out sticks for a market that now stretched as far as the Prairies. Hespeler (in what is Cambridge today), Salyerds in Preston, Hillborn in Ayr, St. Marys Wood Products in St. Marys, Monarch in New Hamburg, Wally in Wallaceburg. In the Ottawa region, were more factories supplying sticks. Sometimes these factories produced sticks under other names for manufacturers like Spalding or the Eatons catalogue. Business was good enough that many of the factories discontinued other lines of products to concentrate on feeding the market for the hockey stick.

The Depression of the 1930s took a toll on Ontario’s stick industry. Factories closed, businesses contracted and jobs were lost. Still, hockey survived. National Hockey League (NHL) star Howie Meeker, who later became a star on Hockey Night in Canada, grew up in Kitchener in the 1930s, where “three of four hockey stick plants” thrived. Meeker’s father delivered bottled drinks for Kuntz’s Brewery. One year, Meeker remembers, the company had a promotion awarding a free stick in exchange for so many bottle caps. “All of a sudden, my dad’s warehouse was full of hockey sticks. So my friends, everyone, had all kinds of sticks to play with.”

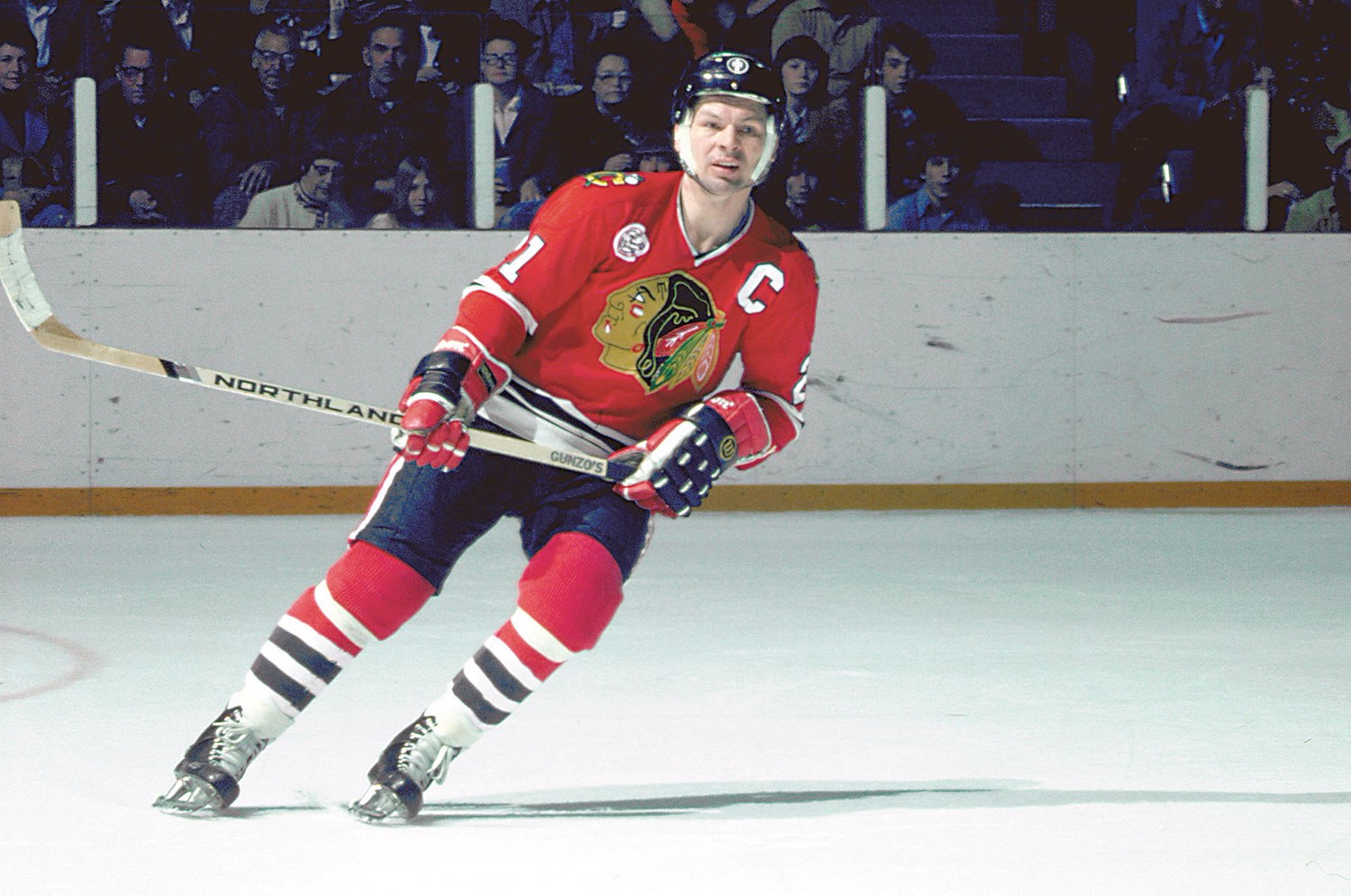

Stan Mikita and Bobby Hull are known for developing the curved blade in the 1960s. The two played for the Chicago Blackhawks and led the team to a Stanley Cup win in 1961. Stan Mikita, the Lester Patrick Trophy winner, playing in a game on March 6, 1976 at the St. Louis Arena, St. Louis, Missouri. (Photo courtesy of the Hockey Hall of Fame)

The names of the sticks were legend, too – Green Flash, Mic-Mac and Blue Flash. For Hall of Famer Bobby Hull, the St. Ann’s native who played junior hockey in Galt and Woodstock, “Hespeler made the best sticks … I used one all season. My father would buy it for me.”

By the time the young Hull was bending his Hespelers with his rocketing slapshot, the construction of the stick itself had evolved. The original models were one-piece affairs, with the blade carved from the roots of the tree (the strongest wood). But they were largely inflexible for the sharpshooters of the NHL. Always searching for the ideal marriage of strength and flexibility in their sticks, designers began incorporating a two-piece and later three-piece design to hold the blade in place. A mortise joint was used to hold the blade and, after some experimentation to find the proper blend, industrial glues were employed to bond the heel.

Ontario remained supreme in sticks until the 1960s when it was challenged by Quebec companies such as Sher-Wood and Victoriaville. Still, the companies in southwestern Ontario flourished – even as they were swallowed up by larger multinational companies, such as Louisville and Nike.

The death knell came when Ontario wood was replaced in hockey sticks by the chemical/engineering marvels of graphite. Sadly, the creation of composite sticks doomed Ontario’s traditional vintage wooden stick industry. Designed in labs, made in China and sold globally, the new generation of sticks is infinitely lighter and can fire a puck faster.

Oldtimers still consider the colourful composites overly prone to breakage, and their cost is 10 or 15 times what a Hespeler retailed for. But the younger generation would no sooner employ a wooden stick than use a rotary phone.