Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Disability in sport

In August 2015, 12 days after the Pan American Games have concluded, the Golden Horseshoe will host the Parapan American Games. These parallel Games for athletes with disabilities will be the fifth time that they have occurred, the first being in Mexico City in 1999.

The Parapan Games are overseen by the International Paralympic Committee, which also oversees the Paralympic Games and provides elite sport opportunities for athletes with spinal cord injuries, cerebral palsy, visual impairment, intellectual disabilities and amputations, along with other disabling conditions. This is not the first time, however, that Canada has hosted a large multi-sport event for athletes with disabilities. Canada – and Ontario in particular – has a long and storied history and role in the Paralympic movement.

Rob Christy of Ottawa, Goalball, Paralympic Games in Beijing, China (2008). Credit: Mike Ridewood. Photo courtesy of the Canadian Paralympic Committee.

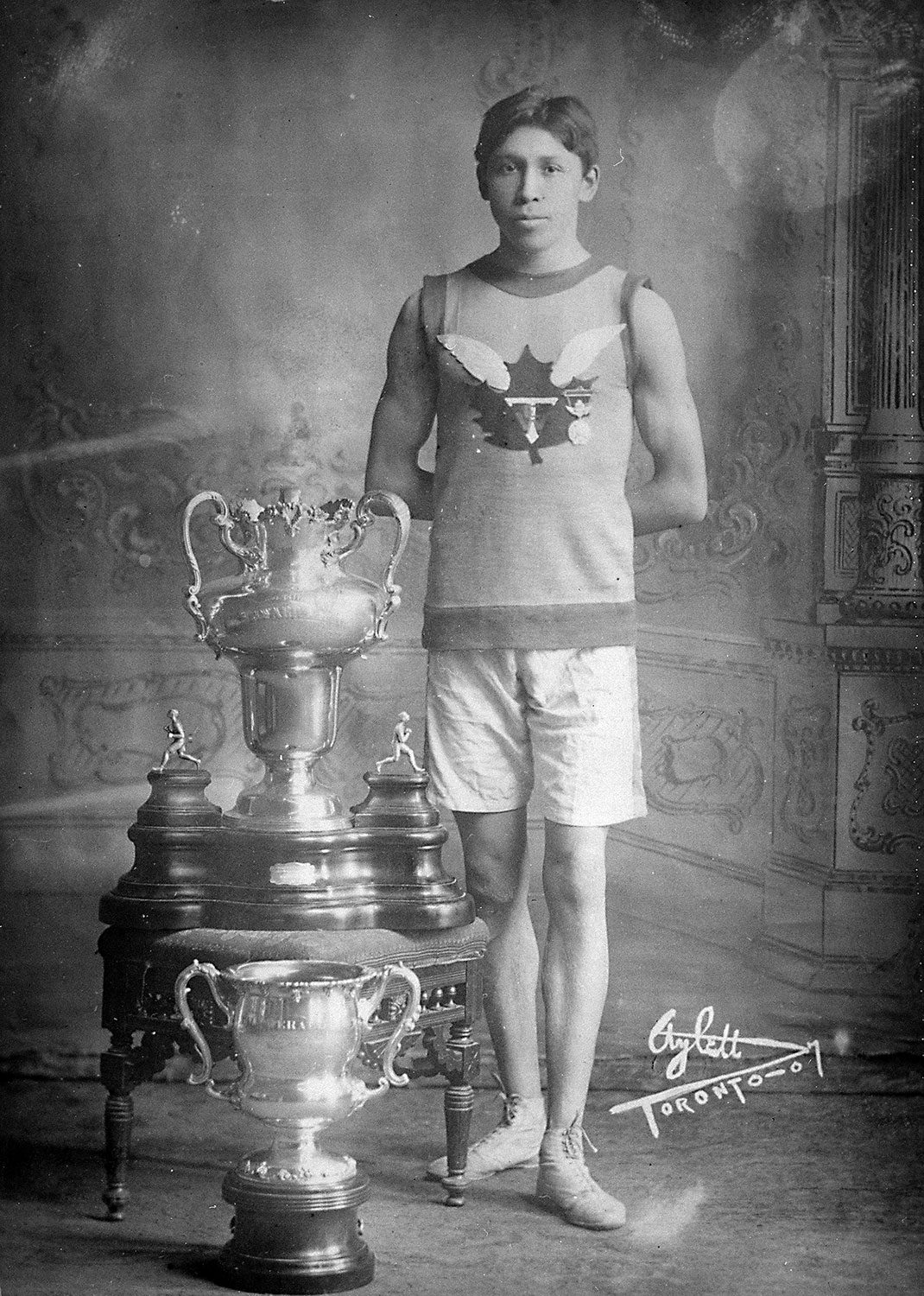

In 1967, Winnipeg wheelchair sport enthusiasts hosted a series of sporting competitions to coincide with the Pan American Games being held that year, although this was not officially recognized as a Parapan American Games. These Games, however, were significant in that the organizers, in attempting to connect with other wheelchair sport organizers from across the country, established the Canadian Wheelchair Sports Association (CWSA) – the first disability sport organization in Canada. Parallel to this was the influence of Torontonian Dr. Robert Jackson.

Dr. Jackson was the orthopedic consultant for the Canadian Olympic team in Tokyo for the 1964 Olympic Games; he then became a visiting fellow at the Tokyo hospital where the second Paralympic Games took place (then called the International Stoke Mandeville Games, after the site where the Games originated in England). The leader of those Games was Dr. Ludwig Guttmann, also a surgeon from England whom Jackson wanted to meet because of his medical reputation. Jackson then requested a meeting with the Canadian delegation, of which there was none. It was here that Guttmann challenged Jackson to bring one to the next Games in 1968, a challenge that Jackson happily accepted. Jackson kept his word and Canada attended their first Paralympic Games in 1968 in Tel Aviv. Jackson also then became the first President of the CWSA.

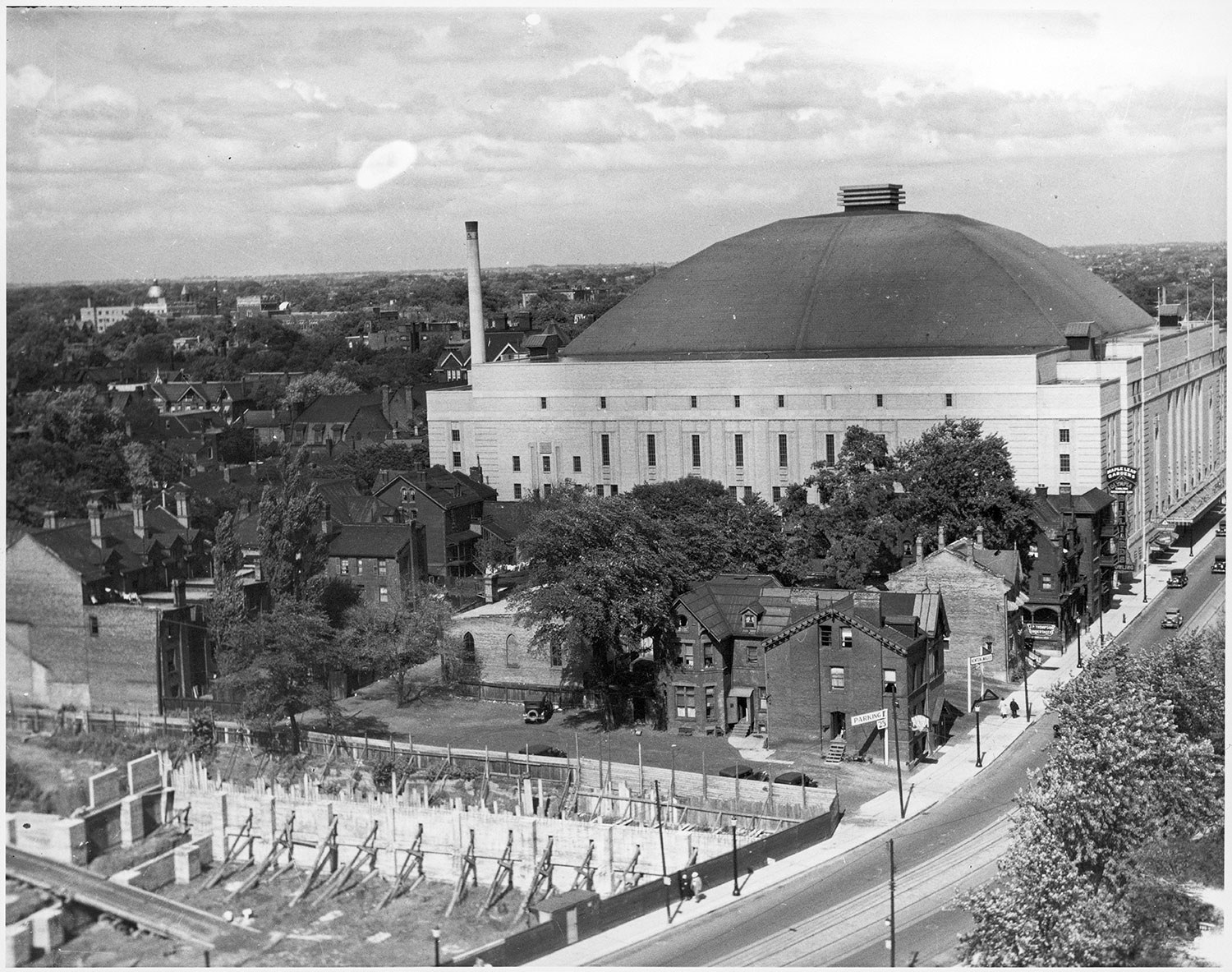

In 1976, Canada hosted the Olympic Games in Montreal. Jackson, having returned to Toronto, agreed to chair the organizing committee for a parallel games for athletes with disabilities. The Games, called the Torontolympiad for the Physically Disabled, were held in Etobicoke’s Centennial Park. These Games turned out to be one of the most interesting – and controversial – Paralympics ever.

The first distinguishing feature of these Games was their inclusion of athletes with disabilities other than those with spinal injuries – such as those with amputations and visual impairments. Prior to this, only those with spinal injuries participated. (Those with cerebral palsy would not be included until 1980.) This would become the model for all future Paralympic sport competitions.

Other factors contributed to make these Games so significant. The 1970s was a time when South Africa and neighbouring countries had apartheid policies, which Canada and most of the world abhorred. Multiple sanctions were put into place to demonstrate international outrage, including the understanding that no country could have sports teams compete against any from South Africa. New Zealand’s rugby team – the All Blacks – in wanting to test themselves against what were perceived as the world’s best, defied this sanction and travelled to South Africa to compete against the Springboks. Outraged nations then alerted the host of the 1976 Montreal Olympics that unless New Zealand was banned from competing, a boycott would ensue. New Zealand was allowed to compete and a number of African nations boycotted the Montreal Olympic Games.

Weeks later, the Torontolympiad faced a similar challenge – except this time, South Africa itself planned to attend. South African teams had competed at the Paralympic Games since Tokyo, and at all of the Games held at Stoke Mandeville in the intervening years (except in 1969).

Until 1975, South Africa had sent alternate teams of Black and white participants to the Stoke Mandeville Games (held annually), although it appears to have been the all-white teams that competed in the Paralympic Games (held every four years to coincide with the hosting of the Summer Olympics).

The Toronto organizers knew that a team from South Africa in attendance created the possibility that the promised Canadian government funding of $500,000 for the Games would be withdrawn. It was eventually decided that South Africa could participate by the hosting committee provided that they brought an integrated team. In the end, South Africa did send a team of around 30 athletes, including nine who were Black.

The ramifications of this event were many. Eight countries withdrew either before or during the Games on the orders of their governments. The Canadian government, true to its promise, also withdrew its funding although they did not prevent the entry of the South African team into Canada.

The local media saw this as a battle worth fighting. On the front page of the March 10 edition of the Etobicoke Guardian was a cartoon of two arms with “federal government” written on the sleeves pushing a Black athlete in a wheelchair wearing a South African jersey, with the caption “Ottawa Threatens to Withdraw its $500,000 in Funding for the Olympiad for the Disabled if its Organizers Invite South Africans.” The public responded with more than 10,000 donations and with ticket sales far exceeding expectations, including the opening ceremony, which was a 20,000-seat sell out. In the end, the organizers were able to break even.

The Canadian government, perhaps feeling sheepish about their decision, decided to use the money set aside for the Games to help fund the creation of various national organizations that became the foundation of the Canadian disability sport system.

The overall impact of the Torontolympiad on both future Paralympic Games and especially on attitudes toward disability and disability sport within Canada was immense. The Games marked the first time that athletes with disabilities were presented by the media on the front pages. Four years later, Terry Fox would continue to push the notion that persons with disabilities could attain astounding athletic feats. Fox’s efforts were followed five years later by those of Rick Hansen. The Torontolympiad also benefited from over 3,000 volunteers, many of whom went on to become the leaders of the disability sport movement throughout Ontario.

Prior to 1976, the Paralympic Games were small, wheelchair-only and relatively unknown Games. As a result, they were rarely influenced by politics. But, in 1976, all that changed. Suddenly, the world media spotlight focused on the Paralympic movement in a way never before encountered.

Despite a rocky and uncertain build-up to the Games, the legacy that they left can still be seen in the organizational structures of disability sport and through the government and public support they receive. It can also be seen in the success of the Paralympic Games today, which has almost trebled in size since the Torontolympiad, and has gone on to become the second-largest multi-sport event in the world after the Olympic Games.