Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

A recipe for early Canadian culinary identity

"Recipes have long since been the vessels for the transportation of this knowledge, with some of the earliest recipes discovered dating back to 1700 BC."

Food, cooking and eating as universal experiences have always been an important part of our identity. As a necessity for survival, food knowledge, traditions and techniques have been taught, learned, changed and passed down between family members, friends and strangers for generations, forming the distinct flavour profiles and defining cuisines that we are familiar with today.

Recipes have long since been the vessels for the transportation of this knowledge, with some of the earliest recipes discovered dating back to 1700 BC. They provide a unique view of a specific time and place. They are a record of our predecessors’ place in the past and how they interacted with and used their surrounding environments.

But recipes are not stagnant. They are flexible and adaptable, able to be tweaked and substituted to suit new environments, climates and ingredients. Some of our favourite recipes that we enjoy in the modern day are in fact ancient. They are a product of knowledge and tradition that span millennia.

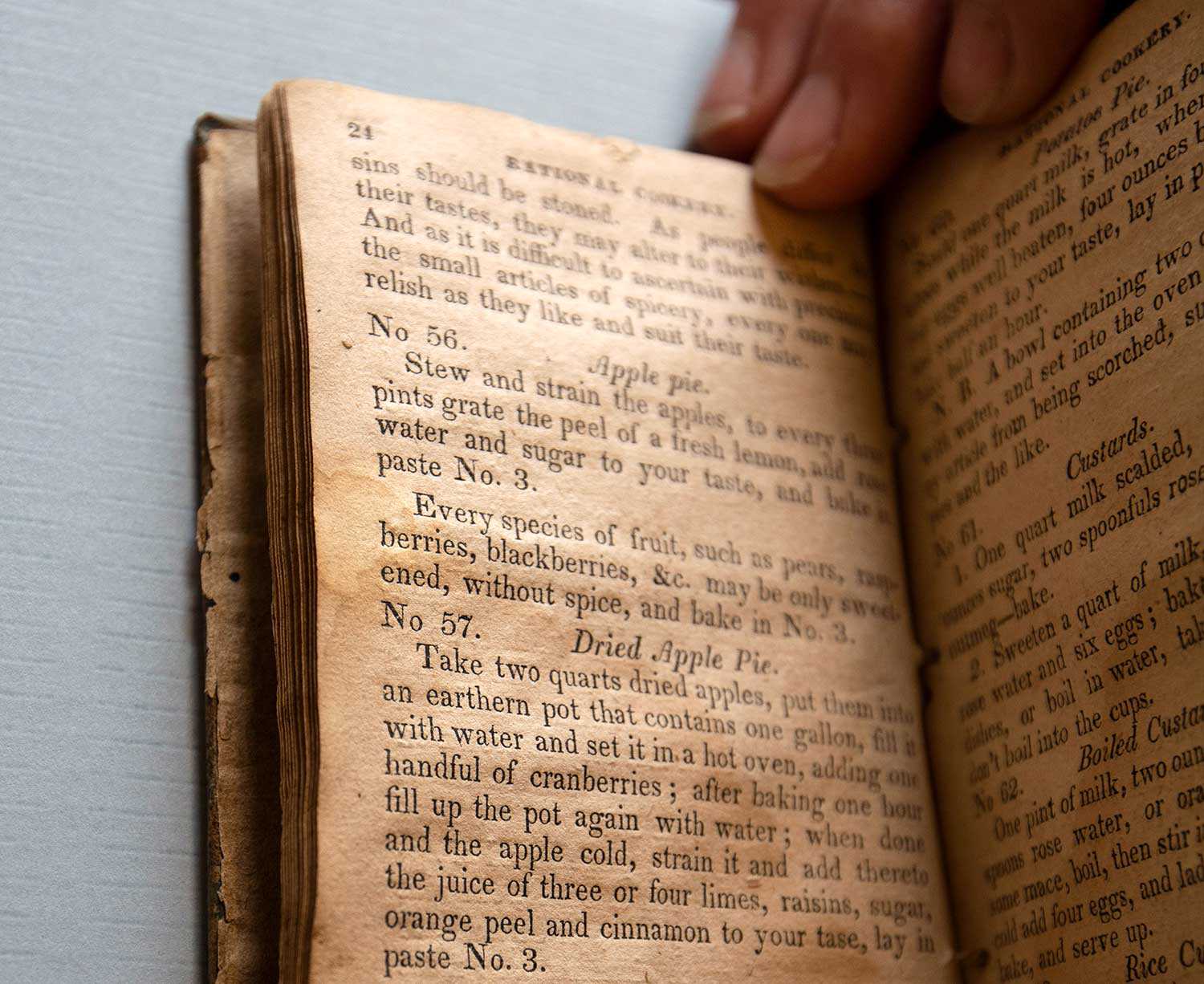

The Cook Not Mad; Or Rational Cookery Book is a collection of recipes that was first published in 1830 in Watertown, New York before it was reprinted in Kingston, Ontario in 1831 by Scottish immigrant James Macfarlane. Today, it is considered Canada’s first English-language cookbook. This historical cookbook is an excellent record of what everyday life would have been like for many Canadians living in the early 19th century. Though this cookbook emphasizes the American character in its "good Republican dishes,” this book also shows how its collection of food knowledge has been taken from different cultures — including First Nations, British, American, Italian, French and Middle Eastern. As such, these collected recipes reflect the diverse peoples that were present in the development of Canada’s early culinary identity.

The food knowledge provided within The Cook Not Mad was collected and published with the purpose of helping new immigrants to North America adapt to the unfamiliar environments, climates and ingredients that now surrounded them. Many of the ingredients featured are wild and farmed meats and locally grown agricultural products that were native to North America. Some of these ingredients include turkey, squash, cornmeal and cranberries, which may not have been easily recognizable to many newly arrived European immigrants. The recipes provided in this book are extremely useful to help us understand the seasonality and utility of the surrounding produce to settlers during early colonialism. These recipes would have also served as instructions for settlers on how to incorporate the available local ingredients into their already existing food knowledge, which they would have brought with them from their homelands.

The new knowledge required to work with these unfamiliar ingredients and to survive in Canada’s harsh environment would have been learned from the Indigenous peoples who already had an ingrained relationship with the land for 10,000 years. First Nations’ food knowledge can be found in numerous recipes throughout this book. One example of this can be seen in recipe No. 205, titled “For Brewing Spruce Beer.” This recipe is a combination of medicinal food knowledge that was incorporated from First Nation peoples (which aided colonists in their survival) and European brewing traditions brought over from settlers’ homelands.

A record of the transfer of this Indigenous knowledge appears in 1536 when French colonist Jacques Cartier and his crew were dying of scurvy while wintering at Stadacona (now Quebec City). They were saved by the Haudenosaunee people who showed them how to steep spruce tips to make a medicinal tea that cured them of their ailments. One cannot help but notice the irony and injustice here between the life-saving knowledge provided by the First Nations people and Jacques Cartier’s later betrayal and abduction of Chief Donnacona, his two sons and several other Iroquoian people who would be forcibly taken from their homeland and never returned.

The piney, aromatic qualities of spruce allowed it to become a popular flavouring agent for brewing beer in many Canadian colonies. Spruce beer was coveted for its ability to stave off scurvy and was used by the British Navy as a staple for long sea voyages. It was also recognized as a hallmark of the North American identity as it was a cheaper option to produce, and its flavour profile was quite different from other European beers. This beverage fell out of favour in the latter half of the 19th century as ciders and meads surpassed beers in popularity. Today, however, there has been a resurgence in this distinctive North American beer as many craft breweries have become interested in reproducing it.

Making one of the recipes from The Cook Not Mad; Or Rational Cookery book during the Trust’s video shoot (shown below).

Another ingredient that appears frequently throughout The Cook Not Mad as a product of cultural transfer is rose water. In the 19th century, rose water was a popular flavouring agent used by early Canadians and Americans for baked goods. Rose water was just as popular a flavour then as vanilla is in today’s confectionaries. It was made by steeping fragrant rose petals in water and provided floral and earthy flavour notes.

The presence of rose water in Canada stemmed from its English colonial identity. In the 17th and 18th centuries, rose water was considered a traditional staple flavour of English baking. The culinary use of rose water, however, has deeper roots in Persia, dating back to the early Middle Ages. It was during the Crusades, when English soldiers invaded the Middle East, that they became accustomed to this flavour, and adapted rose water into the English culinary repertoire. Rose water would then travel to North America a few hundred years later as the favoured flavour for tarts, pies, cookies and custards. It was not until the 1840s when vanilla would completely replace rose water in most recipe books.

Early North American cooking was mainly influenced by season and location. Immense amounts of work had to be done in relation to food production and preservation in order to feed one’s family from season to season, especially in preparation for the harsh winter months, during an era when food preservation technology was still in its early development.

In fact, the first recipes that appear in The Cook Not Mad are instructions on how to preserve meat to be kept throughout the year, which was known as barrelled meat. Barrelled meat was essential for newly established households that were unable to raise enough of their own livestock to feed themselves. It was hard to cook and not considered very tasty. Most immigrants to North America, however, would incorporate barrelled meats into most of their meals, regardless of socioeconomic position. The wealthy inhabitants of Toronto consumed a mix of local and American-raised pigs, while nearly all lower-status rural households only used locally raised pork, which was considered lesser in taste and quality when compared to American, corn-fed pork. By the mid-1800s to early 1900s, preserved pork products became a significant Canadian export. One of the earliest and largest pork processing facilities, the William Davies Company, was located in Toronto. This thriving industry influenced the identity of the city as rows and rows of pig pens would be lined up in front of the processing plant. This visual, along with the quality of the salted pork products being produced, earned Toronto the nickname of Hog Town.

Though the recipes that appear in The Cook Not Mad; Or Rational Cookery book may appear short and sparse (with some barely four sentences long), if given a closer inspection, the foodways held within these instructions can reveal countless interpretations of how past peoples of Canada interacted with each other, as well as with their surrounding environments, and the ingredients available to them. These recipes are also a record of how food knowledge and traditions move, morph and combine in order to transform the unfamiliar into something nourishing that both fortify our collective identities and survival.

Today, this book has been reprinted and its recipes reinterpreted to be used by modern audiences. These recipes both provide a historical archive of the older foodways that inspired them while simultaneously marking the beginnings of a budding cuisine that is now tied to a new time and place.

![Rose Lieberman, Rose [Hanford?] Green and Aaron and Sarah Ladovsky in front of United Bakers restaurant, Spadina Ave., Toronto, 1920. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, fonds 83, file 9, item 16.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/SoupsOn_Archival_3505.jpg)