Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Ontario’s Quiet Revolution

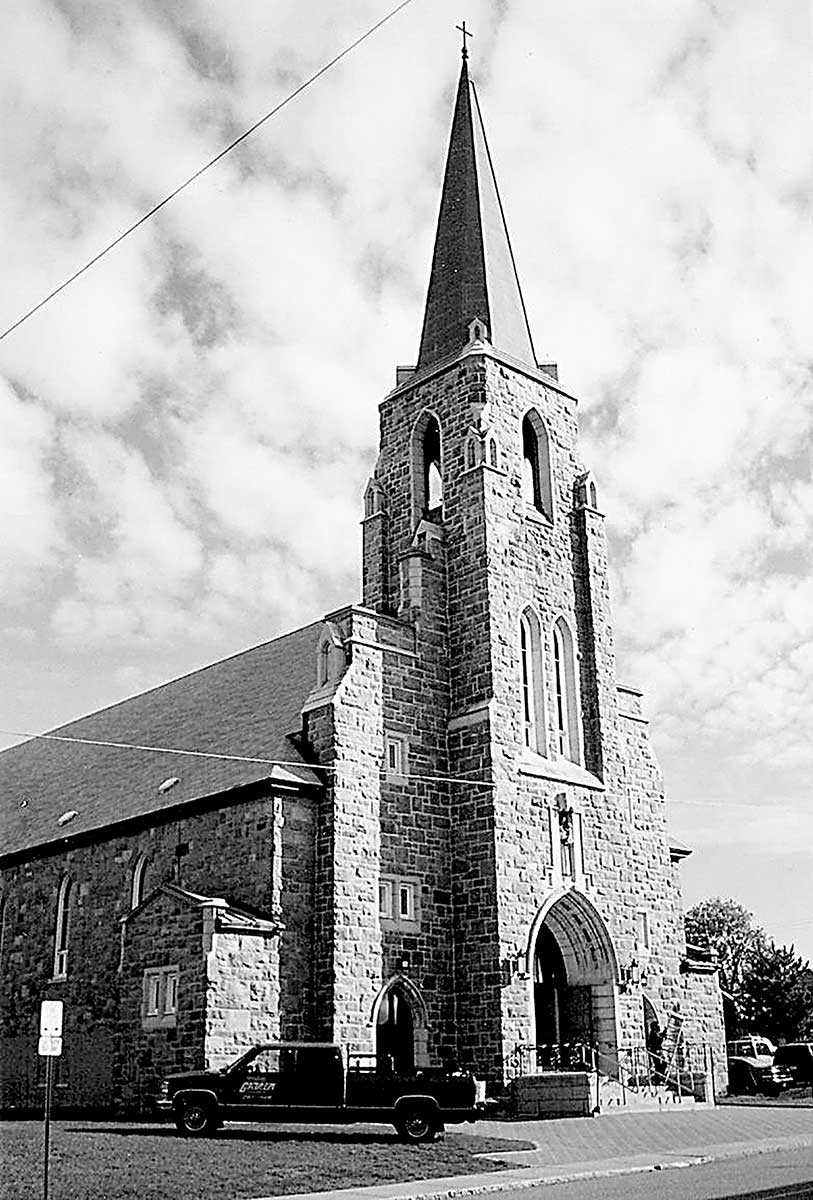

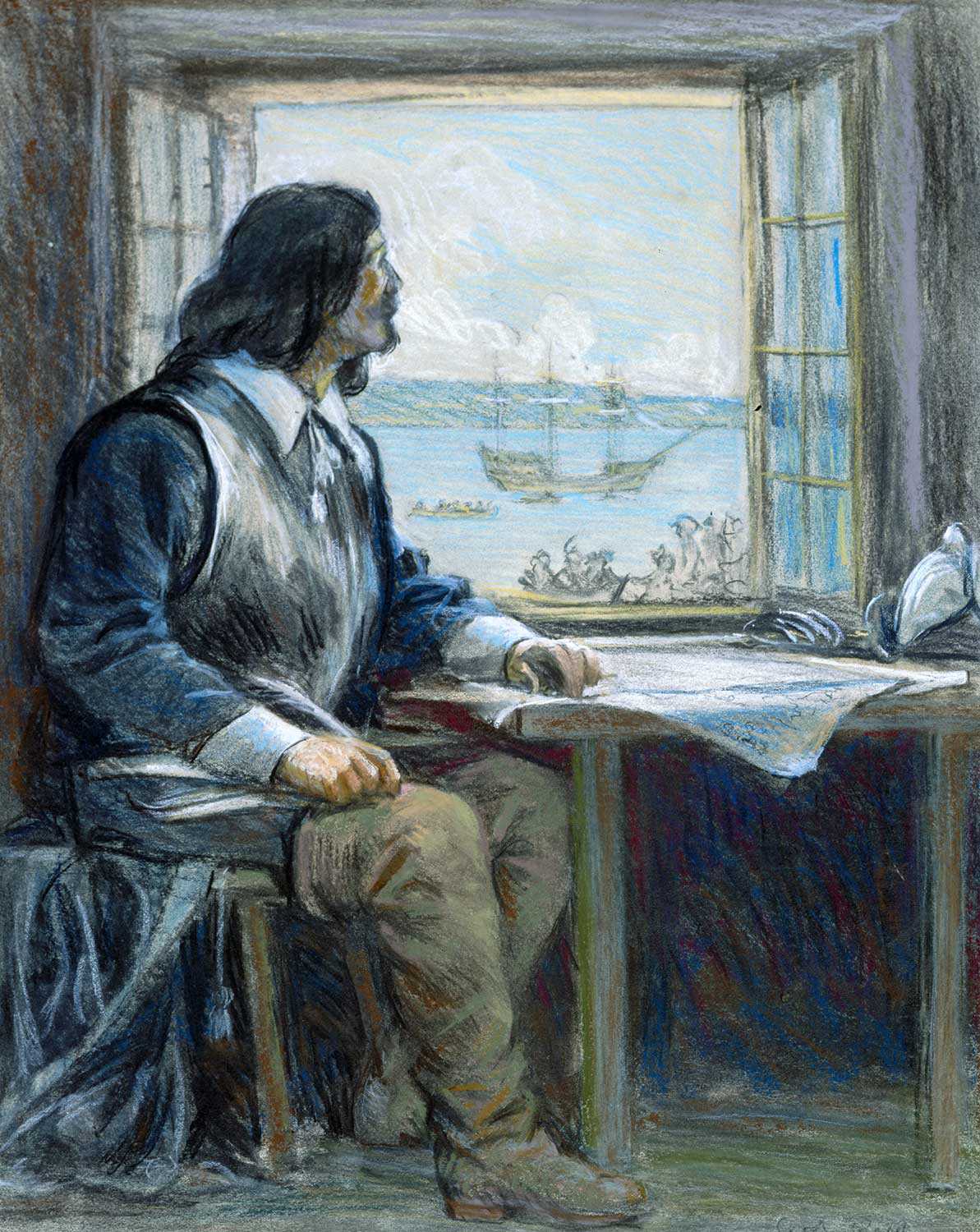

The role of French-speaking people in shaping the history and life of this province reaches back to the early 17th century, when explorers and missionaries embarked on official journeys of reconnaissance and faith.

By the time Upper Canada was created in 1791, the relationship of French-speaking people to the province was well established, and recognized in some of its earliest legislation. In fact, a resolution acknowledging French-language rights in Upper Canada was adopted at Newark as early as June 1793.

This view of the importance of language to the French-speaking population – and to the identity of the province as a whole – was shared by those creating a pre-Confederation educational framework for the province. Indeed, Dr. Egerton Ryerson, the Chief Superintendent of Education in the province for more than 30 years, took the view that French was, as well as English, one of the recognized languages of the province, and that children could therefore be taught in either language in its public schools.

In the almost 100 years, however, from Confederation until Ontario’s own Quiet Revolution in the 1960s, Frenchspeaking people in the province were faced with heavy and real pressures to assimilate, stemming in large part from an assumption that assimilation was both desirable and possible. This assumption significantly influenced the thinking of virtually every provincial administration from the time of Confederation and was supported by a broader movement in English Canada intended to restrict or eliminate altogether the use of French language. Even the passionate opposition of Sir John A. Macdonald, who denounced the movement in the House of Commons in 1890, did little to quell its momentum.

In spite of legislative and other efforts to eliminate the use of French language in the province, the French fact would not go away. This reality was acknowledged by modest gains in education during the period between the First and Second World Wars that culminated in the 1960s during a period of substantive reform.

Indeed, the 1960s saw numerous and profound reforms and innovations – a revolution in regard to the position of Ontario’s francophone citizens and the rights and opportunities available to them, particularly in the areas of education and language.

The passing of French language school legislation in 1969 was accompanied by a growing recognition of the part played in the history and life of the province by the Franco-Ontarian community. Premier John Robarts acknowledged and supported this fact when he stated, “Men and women of French origin have played a significant role in the development of Ontario for more than three centuries … This role continues today through the FrancoOntarian community … Its strength, vitality, accomplishments and potential are immense. Ontario – indeed all of Canada – is far the richer and stronger for the presence of these French-speaking residents.”

Since the 1960s, we have witnessed further legislative reforms, the strengthening of the Franco-Ontarian identity through education at all levels, literature and the arts, and the creation of cultural symbols. This strengthening of identity has enhanced individual rights and educational and cultural opportunities for all Ontarians.

As we embark on the second decade of the 21st century, we are witnessing an ongoing evolution in francophone Ontario that is a significant part of the province’s changing cultural, social and linguistic landscape, resulting in a more diverse community. This change presents exciting opportunities, as well as new challenges, both of which will inform and enrich our understanding of the French experience in Ontario.

![The family of Simon Aumont. Only Simon himself and Irène (seated, holding a doll), survived the great fire that devastated the region in 1916, Val Gagné (Ontario), [before 1916]. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the collection of Germaine Robert, Val Gagné, Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Frenette-Ph23-VG-3-web.jpg)

![Students demonstrating against Regulation 17 outside Brébeuf School on Anglesea Square in Ottawa’s Lowertown, in late January or early February, 1916 / [Le Droit, Ottawa]. University of Ottawa, Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario archive (C2), Ph2-142a.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Cecillon-Ph2-142a-web.jpg)