Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Prayers, petitions and protests: The controversy over Regulation 17

Francophone heritage

Published Date: May 18, 2012

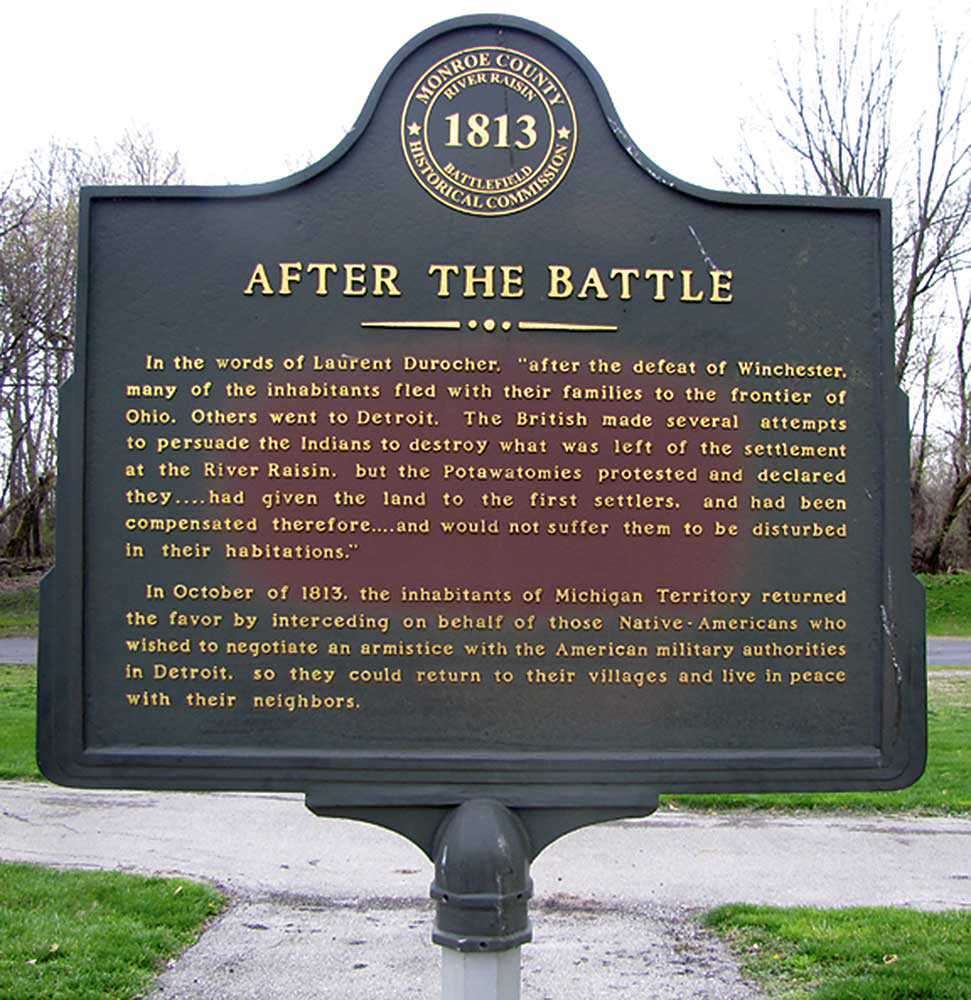

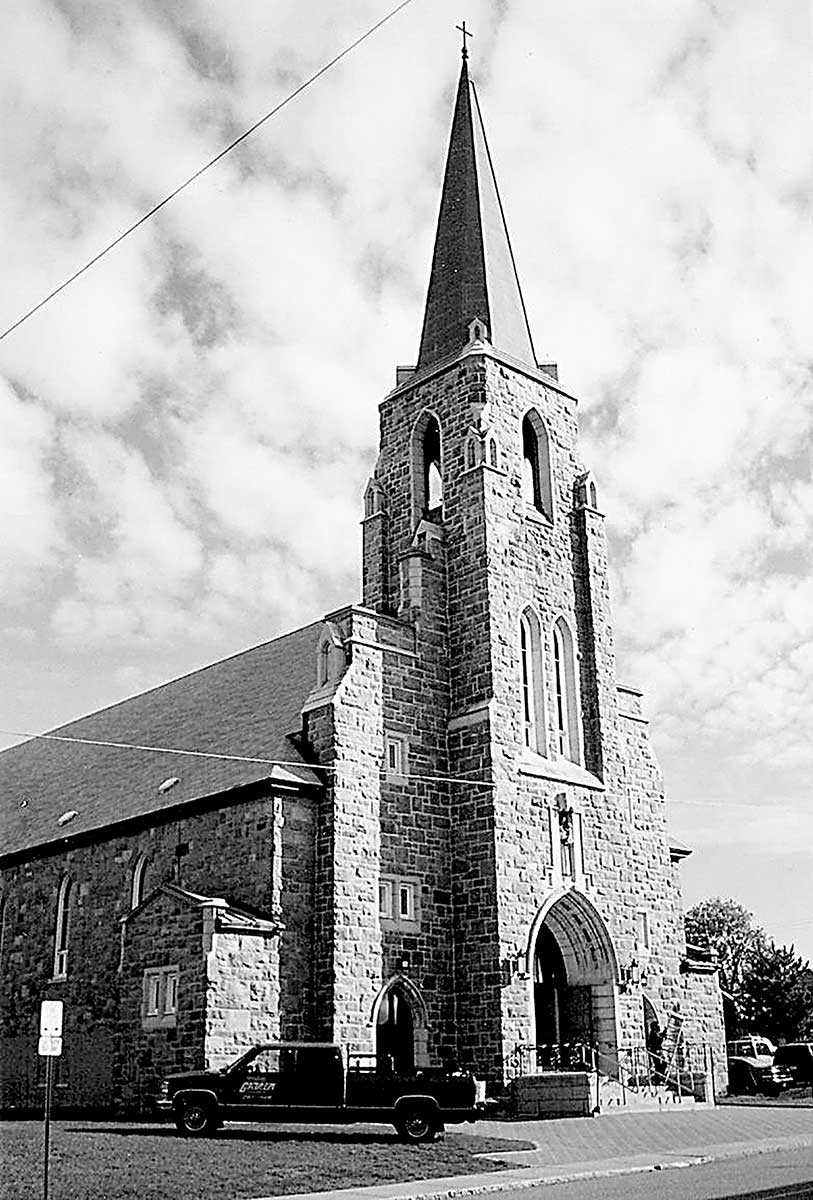

Photo: Students demonstrating against Regulation 17 outside Brébeuf School on Anglesea Square in Ottawa’s Lowertown, in late January or early February, 1916 / [Le Droit, Ottawa]. University of Ottawa, Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario archive (C2), Ph2-142a.

In 1912, after an inquiry into the state of Ontario’s bilingual schools, the provincial government of Conservative Premier James Whitney introduced Regulation 17, placing tight new restrictions on the use of French as a language of instruction.

The provincial superintendent, Frederick Merchant, reported serious weaknesses in these schools – most notably the preponderance of unqualified instructors, many of whom could not even speak proper English. Regulation 17 restricted the use of French to the first two years of elementary school, while subsequent years eventually secured a one-hour daily lesson per classroom. Henceforth, English was to be the language of every classroom in the province.

This school regulation followed similar reforms in the Northwest Territories and Manitoba at the end of the 19th century. In an era of British imperialism, most English Canadians believed in Dalton McCarthy’s vision for Canada of “One Language, One Flag and One Country.”

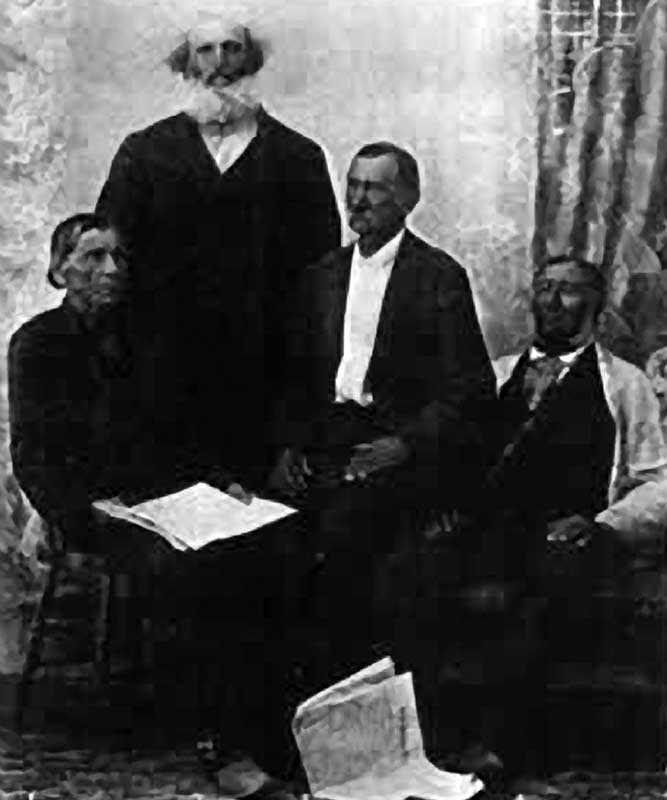

Meeting of the local French-Canadian priests of the area at the rectory of Our Lady of the Lake parish, later the scene of a riot. In the middle of the bottom row among the priests was Henri Bourassa, the famous French-Canadian nationalist leader from Montreal. (Source: Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, University of Ottawa)

The French-speaking communities of Ontario, however, did not accept this education reform quietly. In Ottawa, their leading cultural organization, the Association canadienne-française d’éducation de l’Ontario (ACFEO) urged its compatriots to resist the regulation. Teachers were encouraged to teach more than the prescribed hour of French, while parents instructed their children to march out of the schools on the arrival of the provincial school inspector, a Protestant, who they regarded as an intruder into their Catholic institutions.

In October 1913, when the inspector visited a school in the village of Pain Court, the children marched out of the school singing O Canada, preventing him from doing an adequate inspection. Similar scenarios occurred across the province, but not without consequences. In Tilbury, for example, when the inspector arrived at an empty school, he announced that the local board would not receive its annual provincial grant.

Emotions sometimes reached a boiling point and even led to acts of violence. For instance, during the 1914 provincial election campaign, when Conservative candidate Colonel Paul Poisson held a rally in McGregor, a group of young men screamed and yelled insults at Poisson from outside the hall. When that failed to disrupt the meeting, some of the men began hurling rocks through the windows. Amid the sounds of shattering glass, Poisson continued his speech defending the government’s policy until one projectile – a rotten egg – came crashing down on his shoulder, bringing the rally to an abrupt end. Poisson lost the riding to a vocal critic of Regulation 17.

In 1916, at Ottawa’s École Guigues, a group of mothers formed a human chain around their school to prevent the police from evicting two recalcitrant teachers. When the officers arrived, the women pulled out their long hairpins and kept the officers at bay.

Senator Gustave Lacasse speaks to a group of French Canadians in Tecumseh, Ontario, to protest the appointment in October 1918 of Fr. François Xavier Laurendeau as the new pastor of Our Lady of the Lake Parish in the Windsor suburb of Ford City. Fr. Laurendeau was suspected of being against the bilingual schools. (Source: Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, University of Ottawa)

The following year, in the Windsor suburb of Ford City, French-Canadian parishioners at Our Lady of the Lake Church formed a blockade and then rioted when police attempted to install a new pastor deemed to be an opponent of the bilingual schools and a supporter of Bishop Michael Francis Fallon. Fallon had publicly called for the elimination of the bilingual schools to protect the Catholic separate school system from its critics, becoming the enemy of French-Canadian nationalists everywhere. The Ford City riot led to nine arrests and 10 injuries, including two women in their 70s. The parishioners appealed to the Vatican to reverse the bishop’s pastoral appointment, but to no avail; they were ordered to accept the priest in question or face excommunication. In October 1918, they relented, ending a year-long standoff.

Unlike most Franco-Ontarians, however, the majority of francophones in the Windsor border region willingly submitted to Regulation 17, after only modest protests. English was the language of the region, and children had a better chance of securing employment if their English language skills were solid.

Unlike the other communities of French Ontario, where the resistance experienced far greater success, only 10 of the region’s 30 bilingual schools showed any meaningful signs of resistance against the school inspector. In 1926, Premier G. Howard Ferguson announced his plans to reform this school policy that had contributed to a national unity crisis. Still, Ferguson trumpeted that the Windsor border region represented the one shining example of Regulation 17’s success, with inspectors praising the area’s francophone children for their considerable fluency in spoken and written English.

The spirit of French-Canadian nationalism rooted in a careful preservation of the mother tongue did not override the parents’ desire that their children master the English language, at least in southwestern Ontario.

![Students demonstrating against Regulation 17 outside Brébeuf School on Anglesea Square in Ottawa’s Lowertown, in late January or early February, 1916 / [Le Droit, Ottawa]. University of Ottawa, Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario archive (C2), Ph2-142a.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Cecillon-Ph2-142a-web.jpg)

![The family of Simon Aumont. Only Simon himself and Irène (seated, holding a doll), survived the great fire that devastated the region in 1916, Val Gagné (Ontario), [before 1916]. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the collection of Germaine Robert, Val Gagné, Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Frenette-Ph23-VG-3-web.jpg)