Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

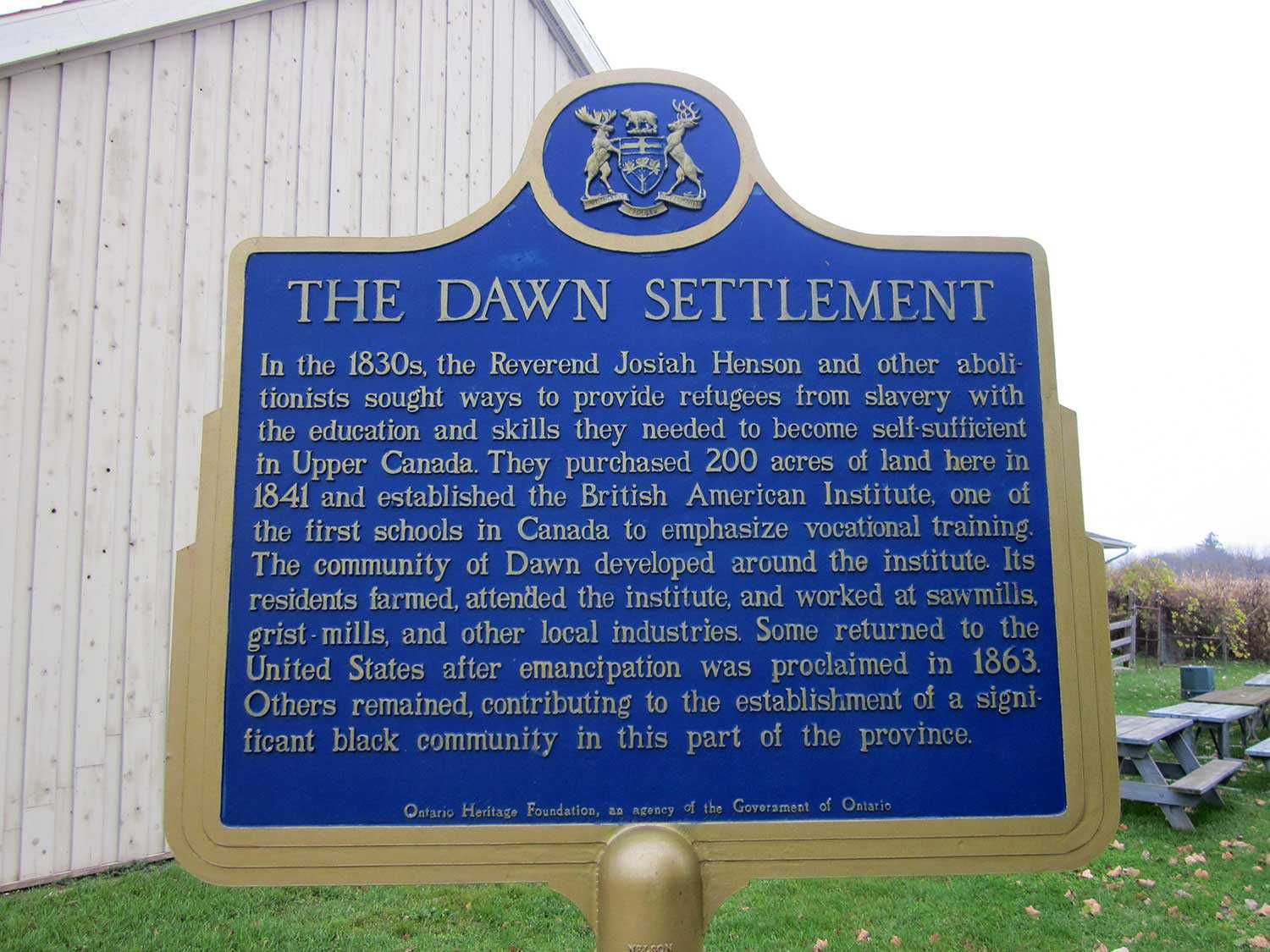

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Ontario's eastern treasures

Buildings and architecture, Community

Published Date: Feb 12, 2009

Photo: Statue of Samuel de Champlain, Ottawa (Photo © Ontario Tourism, 2009)

Inhabited by Aboriginal Peoples for 7,000 years, present-day eastern Ontario is rich with heritage. The area gradually transformed as French and later United Empire Loyalists migrated to the province. As early communities grew, some of Ontario’s most distinctive commercial and cultural centres, transportation and communication routes, defence installations and political institutions emerged. Today, eastern Ontario’s communities, traditions and people offer a unique glimpse of Ontario’s past.

Eastern Ontario encompasses the land situated east of Frontenac County, including Hastings, Lanark, Leeds and Grenville, Lennox and Addington, Prescott and Russell, Prince Edward, Renfrew, Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry counties and Ottawa. Geography has played a key role in shaping the area’s history. To the north, the Ottawa River separated the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. The St. Lawrence River to the south formed the natural boundary between Canada and the United States. The Rideau Canal, running from Kingston to Ottawa, connected these waterways – transportation and communication routes that influenced migration and settlement, industry and trade, politics and defence. And, to the west, the Trent Severn Waterway – running from Trenton to Georgian Bay – was constructed over a period of 80 years. Originally intended for commercial traffic, this waterway became one of the province’s primary recreational attractions.

Archaeological sites show that Aboriginal Peoples who hunted, fished and lived throughout this part of the province also established communities and complex societies. The Akwesasne Mohawks continue to reside on both sides of the St. Lawrence. Their descendants have lived in this region of Ontario long before the establishment of either Canada or the United States.

The relationship of Aboriginal Peoples to eastern Ontario is also rooted in the province’s loyalist heritage. During the American Revolution, Mohawk allies to the British were forced from their ancestral homeland in present-day New York State. To compensate for this loss, the Crown gave land to the Mohawks and others displaced by the revolution. As a Mohawk ally serving in the British Army, Captain John Deserontyon selected land on the shores of the Bay of Quinte. In 1784, approximately 20 families arrived at their new home, thus marking the beginning of Mohawk settlement on the Bay of Quinte (today’s Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory). The arrival of the Mohawks on the Bay of Quinte is recognized as a National Historic Event.

In Renfrew County, Irish and later German and Polish immigrants faced many challenges and hardships while transforming the rocky wilderness into farms and homesteads that grew into communities such as Wilno. © Ontario Tourism, 2009.

In the 17th century, Europeans began visiting the area. In 1610, the French explorer Samuel de Champlain sent Étienne Brûlé, one of his followers, to live among the Algonquian or Anishinabeg to learn their languages and gather information. In 1613, Champlain travelled up the Ottawa River and other waterways to the Pembroke area before turning back. He engaged in diplomacy with the Algonquian people and later became the first European to write a description of the region. He returned to the Ottawa River in 1615 and later led a small party of Frenchmen with a large force of Hurons and Algonquians down the Trent River to attack an Onondaga village near present-day Syracuse.

The French presence in Ontario grew in the late 17th century when fortified fur-trading posts and missions were built at present-day Kingston and elsewhere. French influence diminished with the fall of New France, although an influx of Quebecois workers to eastern Ontario created vibrant francophone communities through the St. Lawrence River area and elsewhere.

A number of provincial plaques in Kingston and the surrounding area tell the stories of trade and settlement during the French regime in what is now eastern Ontario. In particular, plaques in Kingston’s City and Confederation parks commemorate the establishment of Fort Frontenac and the Cataraqui settlement at the site of the present-day city. A plaque in Cornwall recognizes more recent French heritage by telling the story of the many workers and tradesmen who established a vibrant and lasting community in that city.

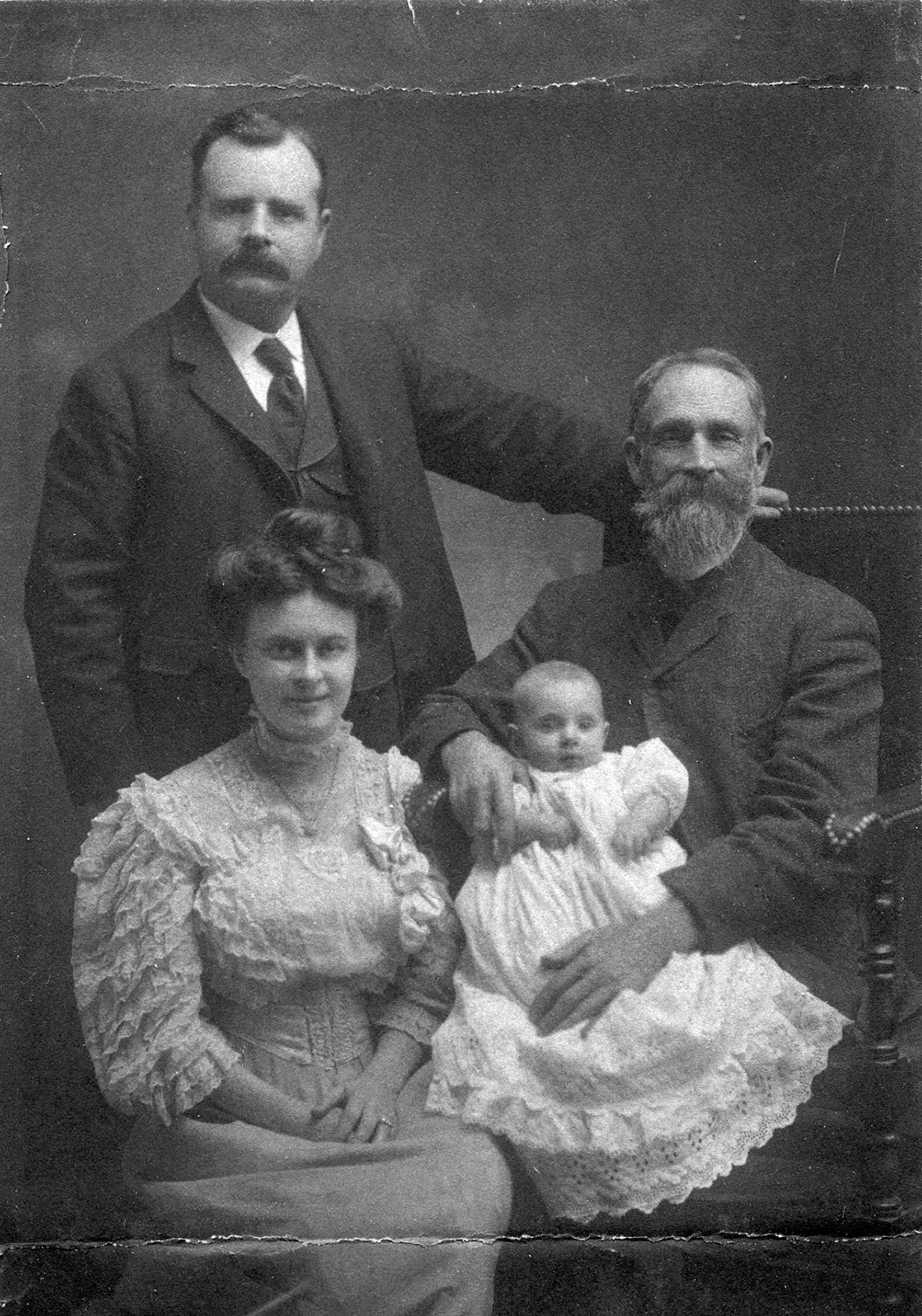

Early communities along Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence grew out of the aftermath of the American Revolution in 1783 when British Loyalists resettled throughout eastern Ontario. Many of these Loyalists were soldiers who came to Canada with their families after having lost their homes and peacetime livelihoods. They brought with them the desire to live as loyal subjects under British laws and institutions.

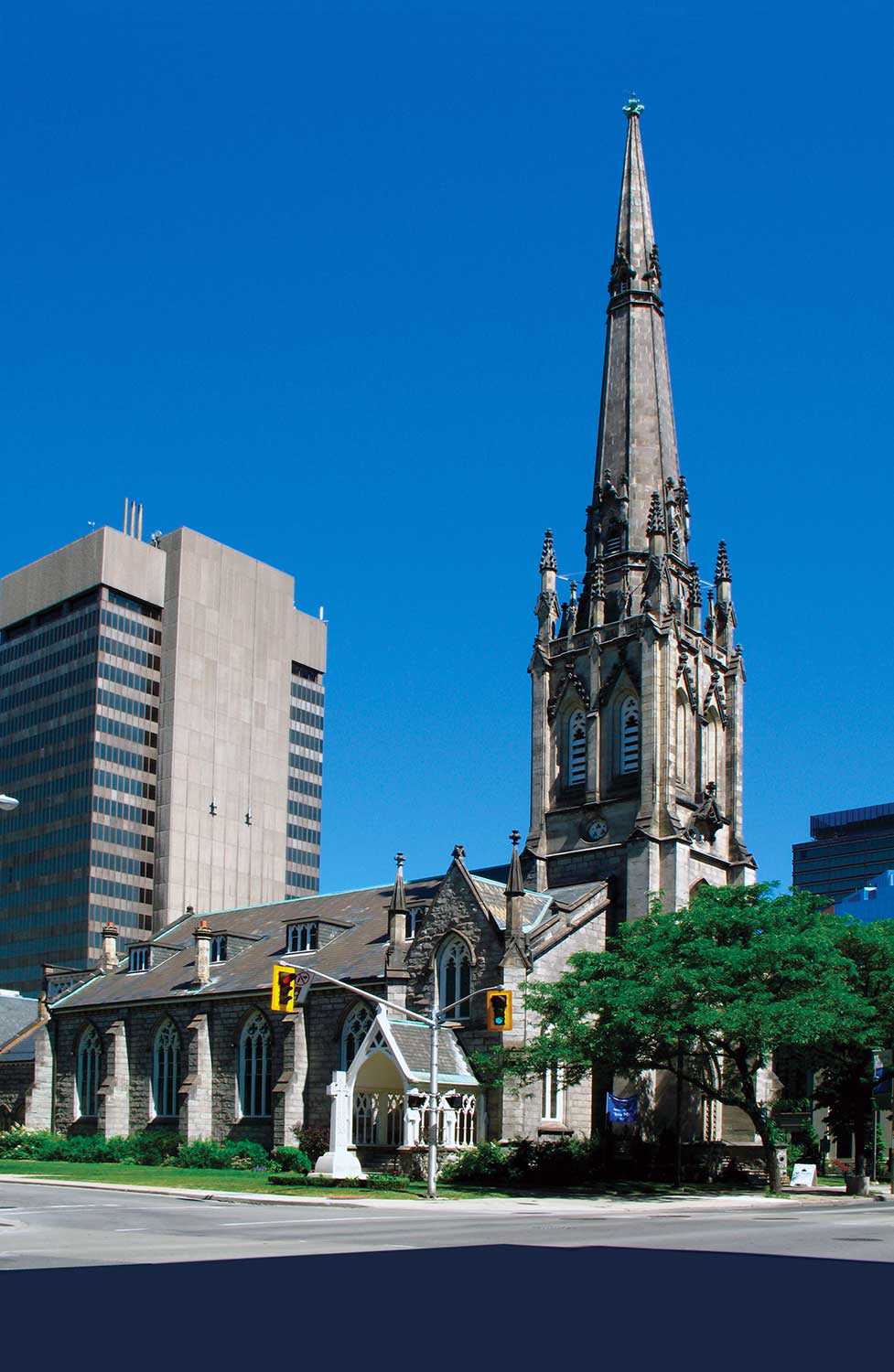

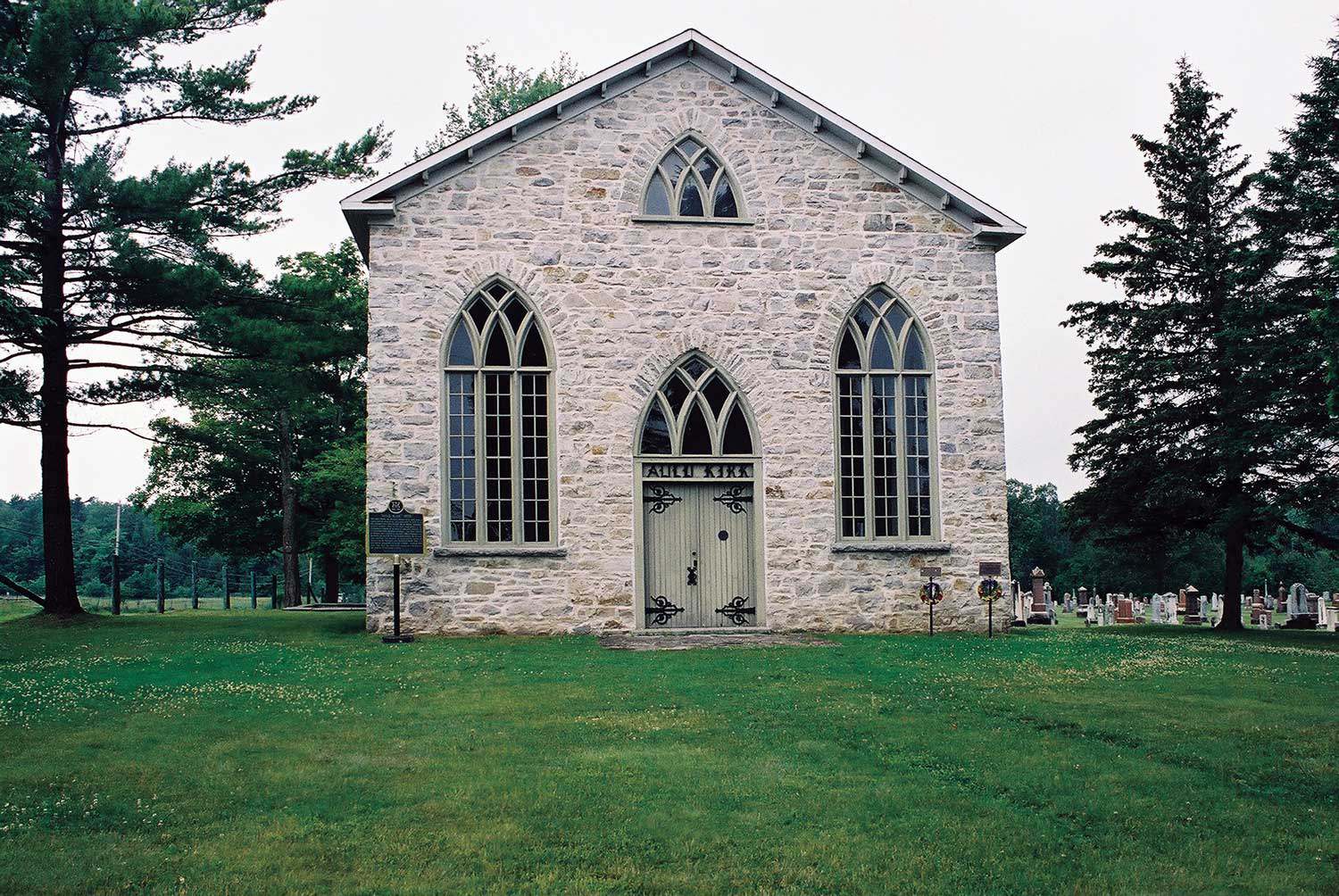

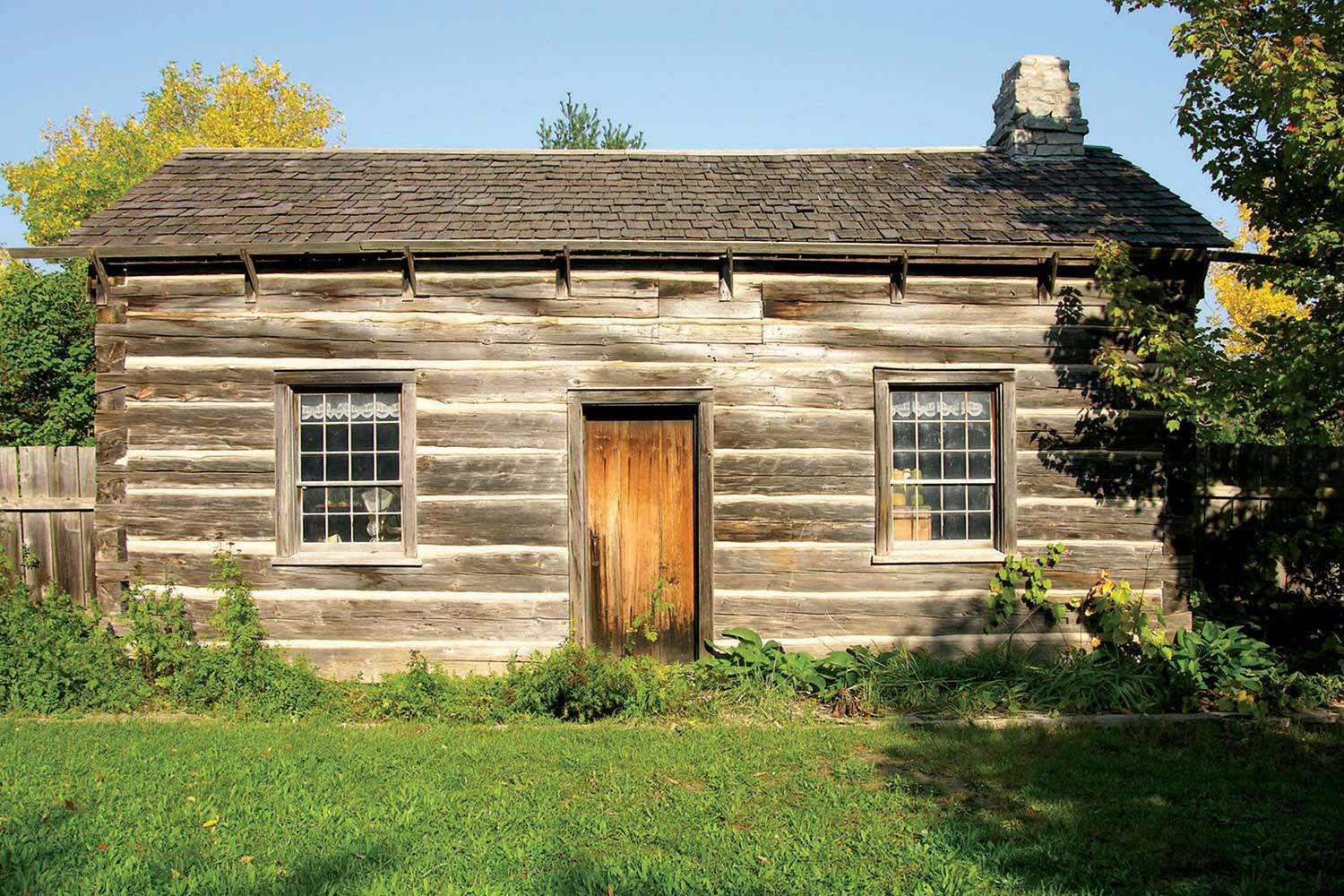

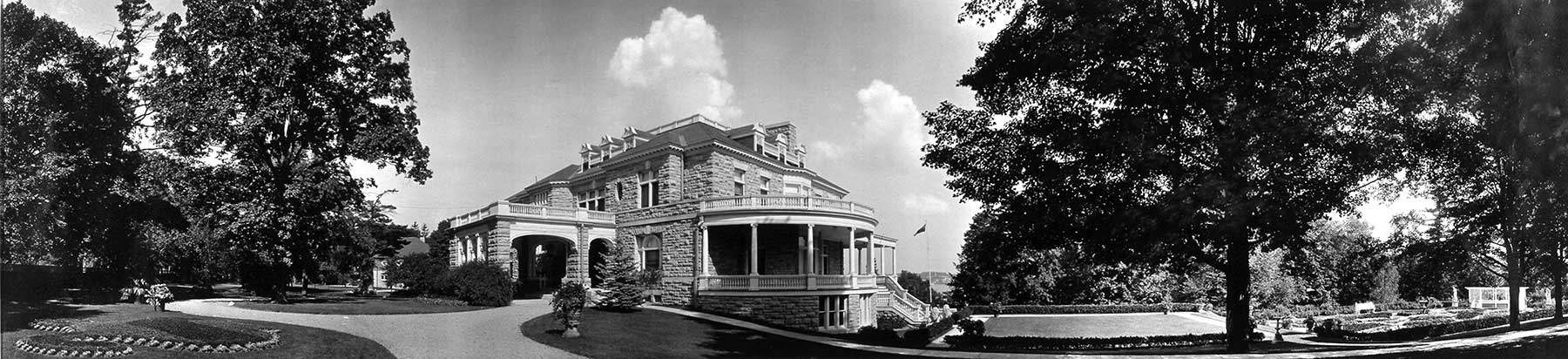

Some of Ontario’s oldest structures are found in this area – Hawley House in Bath, built about 1785 by Vermont Loyalist Captain Jeptha Hawley, and Homewood in Maitland, built in 1799 for Dr. Solomon Jones. Strong British influences and heritage can also be seen in the architecture and traditions of communities settled by Loyalists and later British immigrants. Robust stone buildings were built by Scottish masons from locally quarried limestone. Names such as Cornwall, Williamstown, Glengarry, Brockville, Kingston and Bath speak to the area’s British heritage.

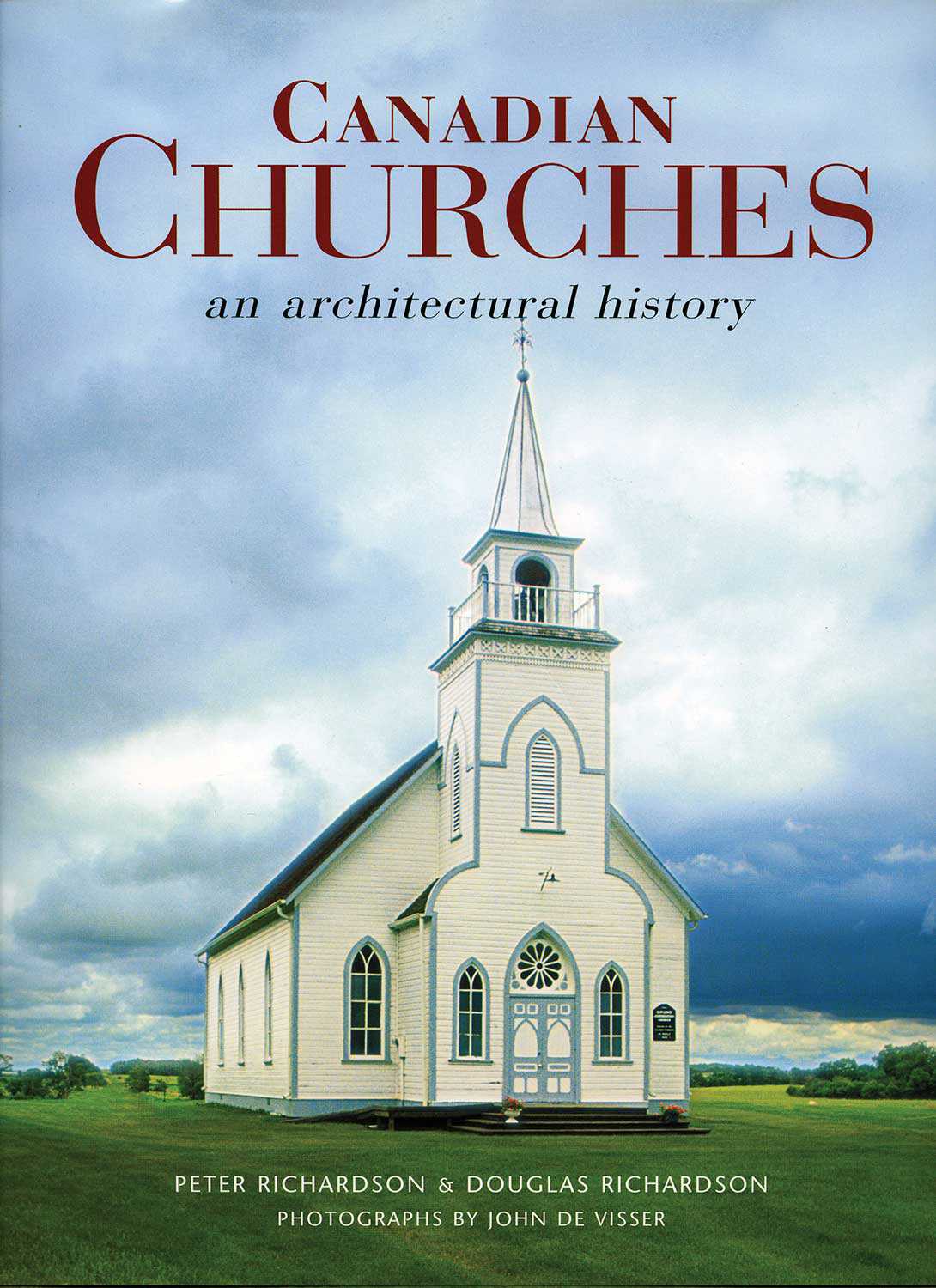

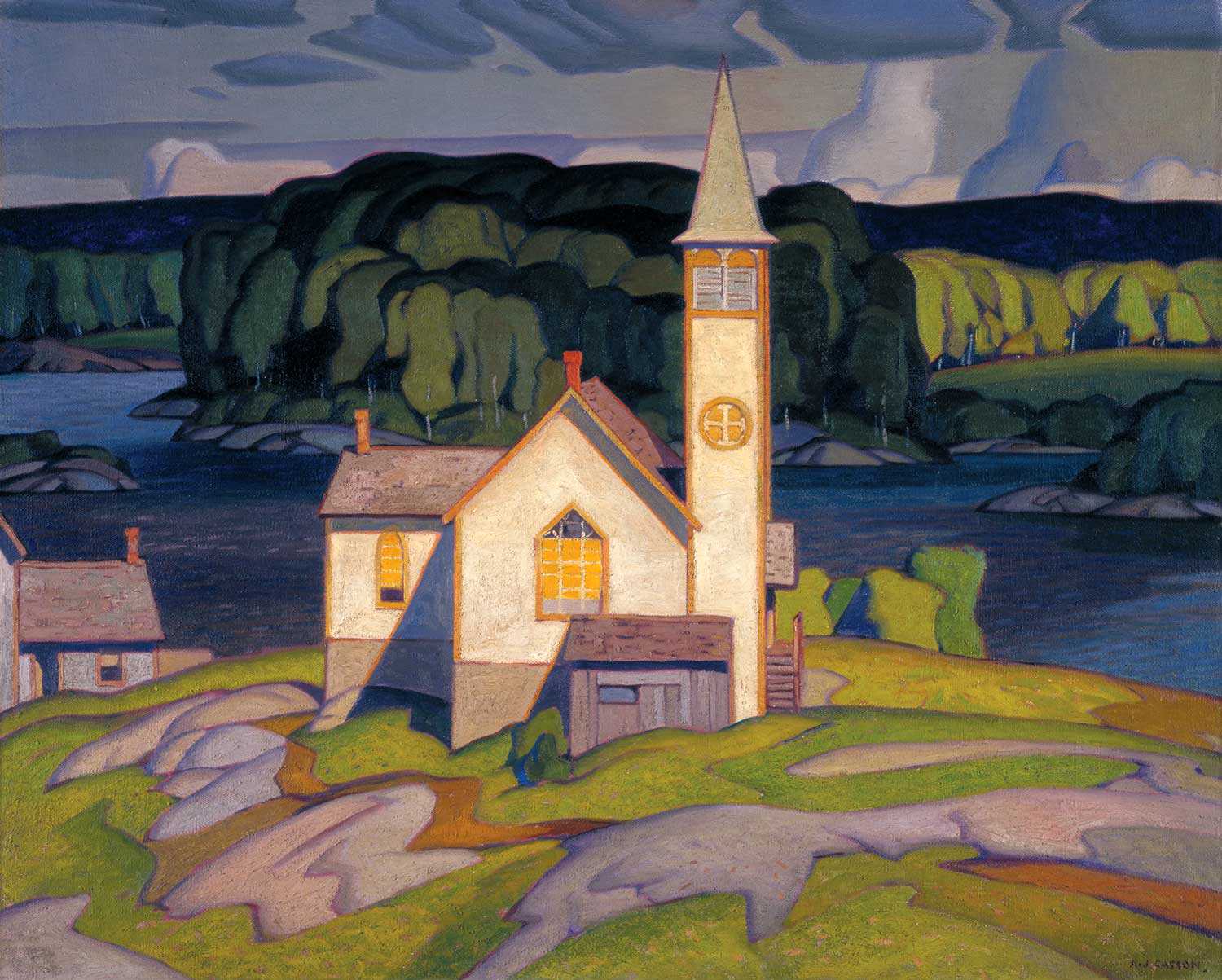

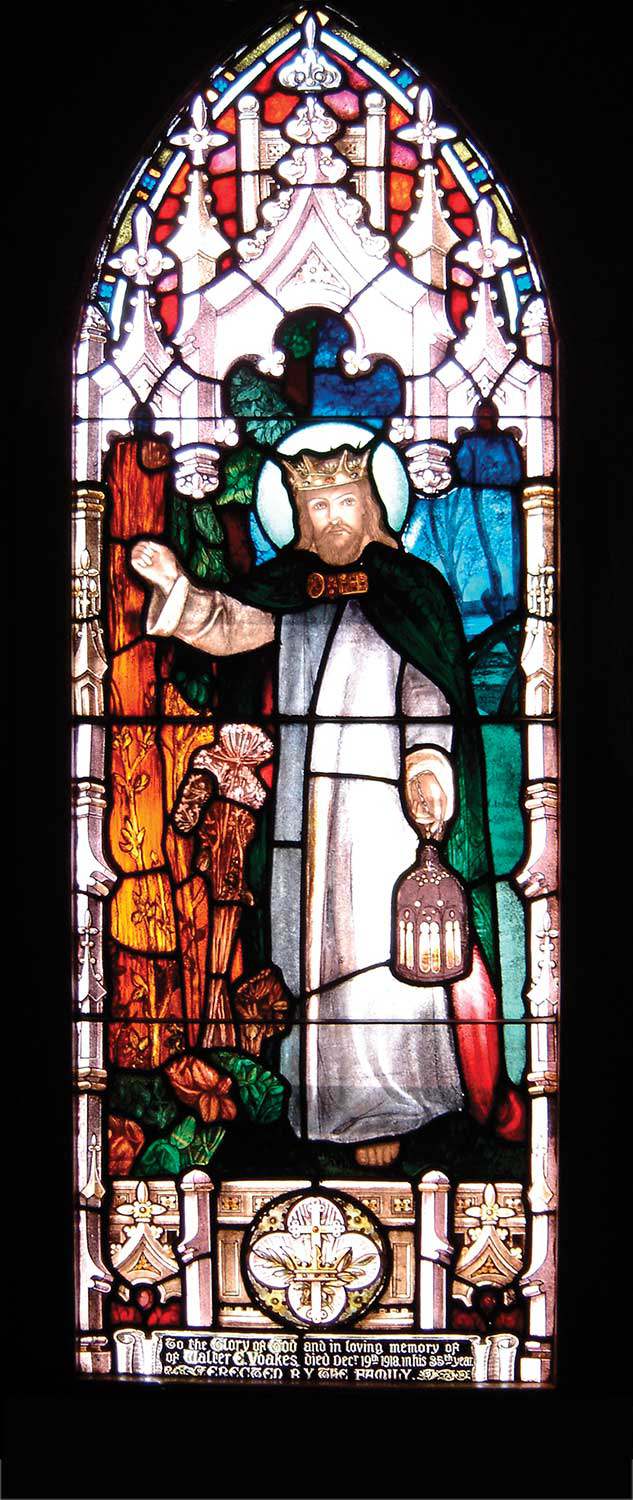

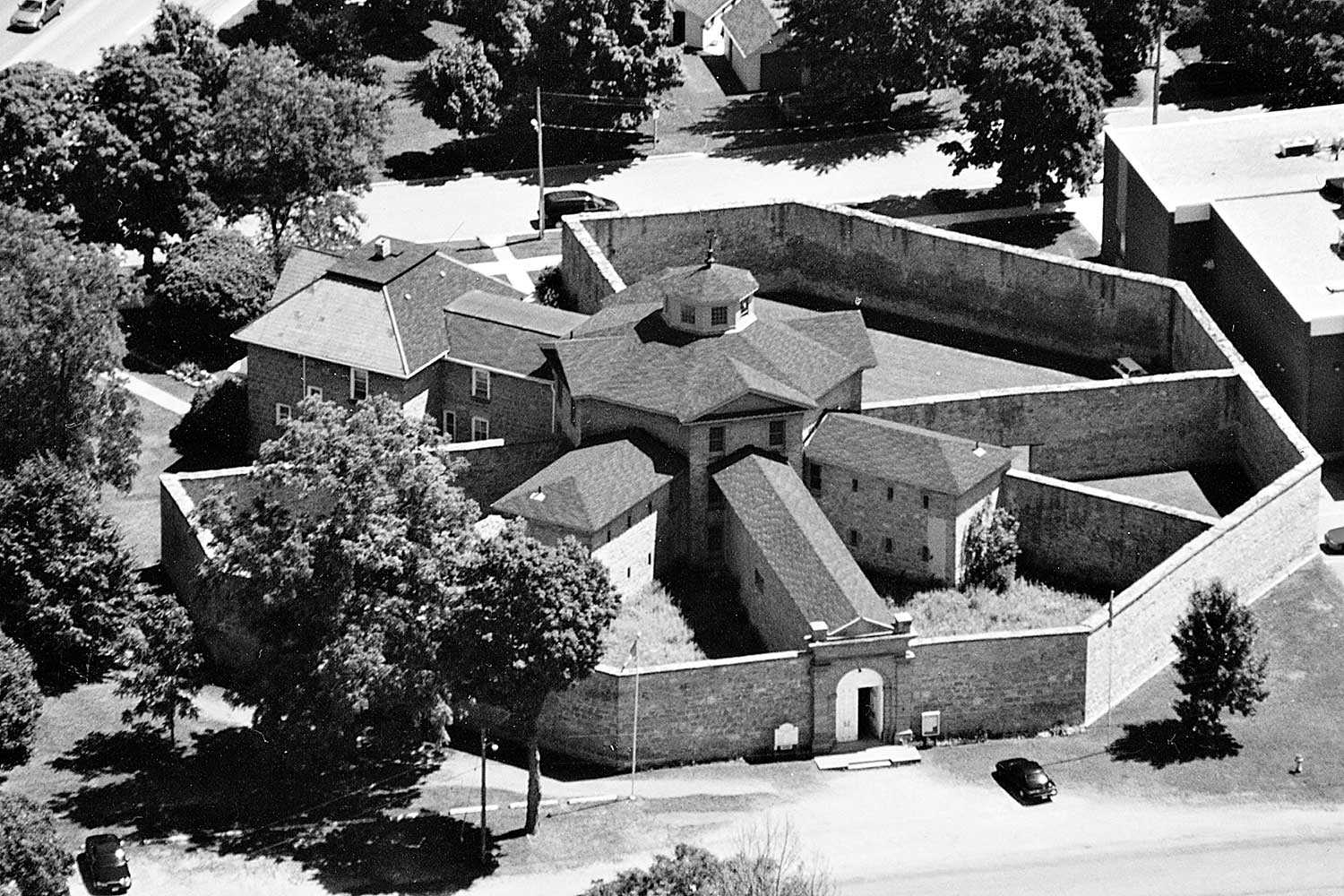

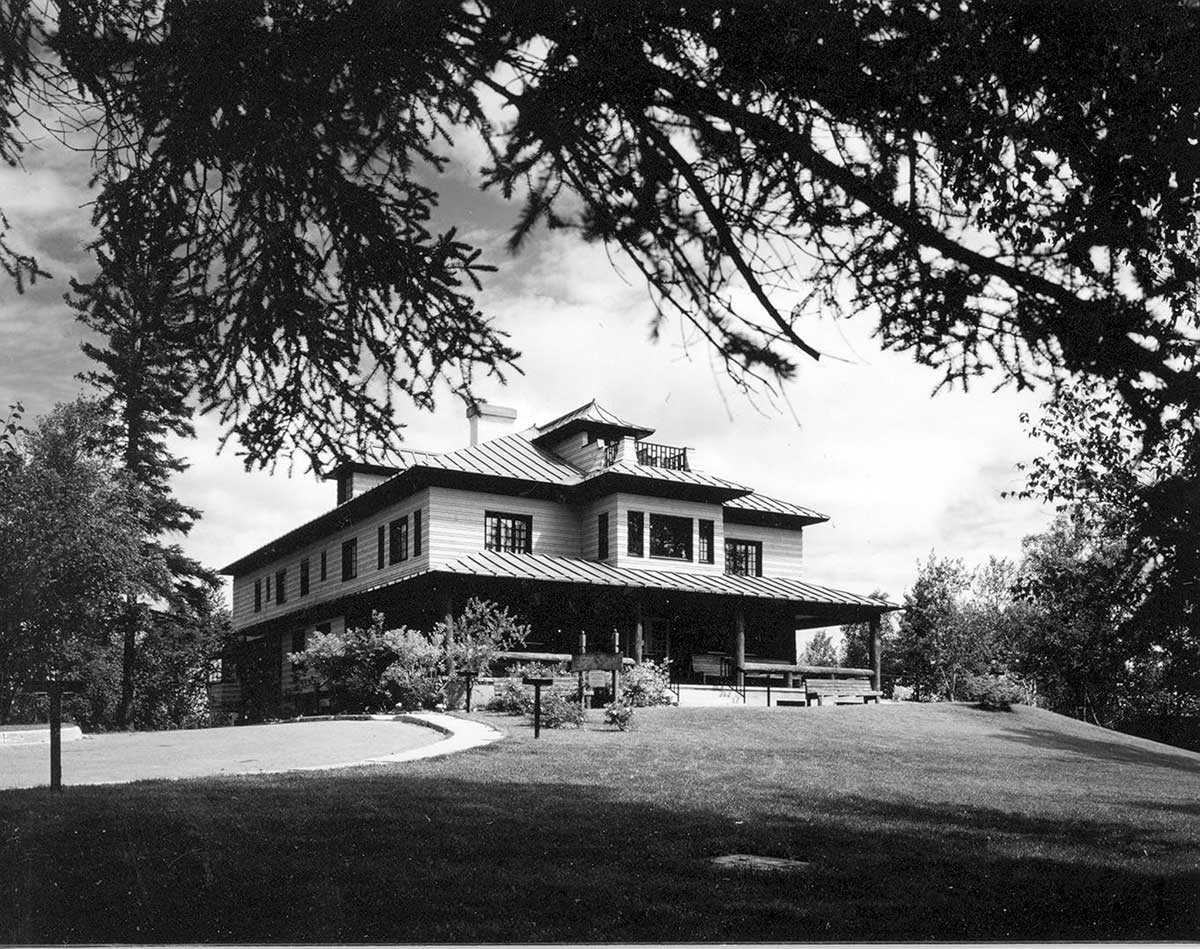

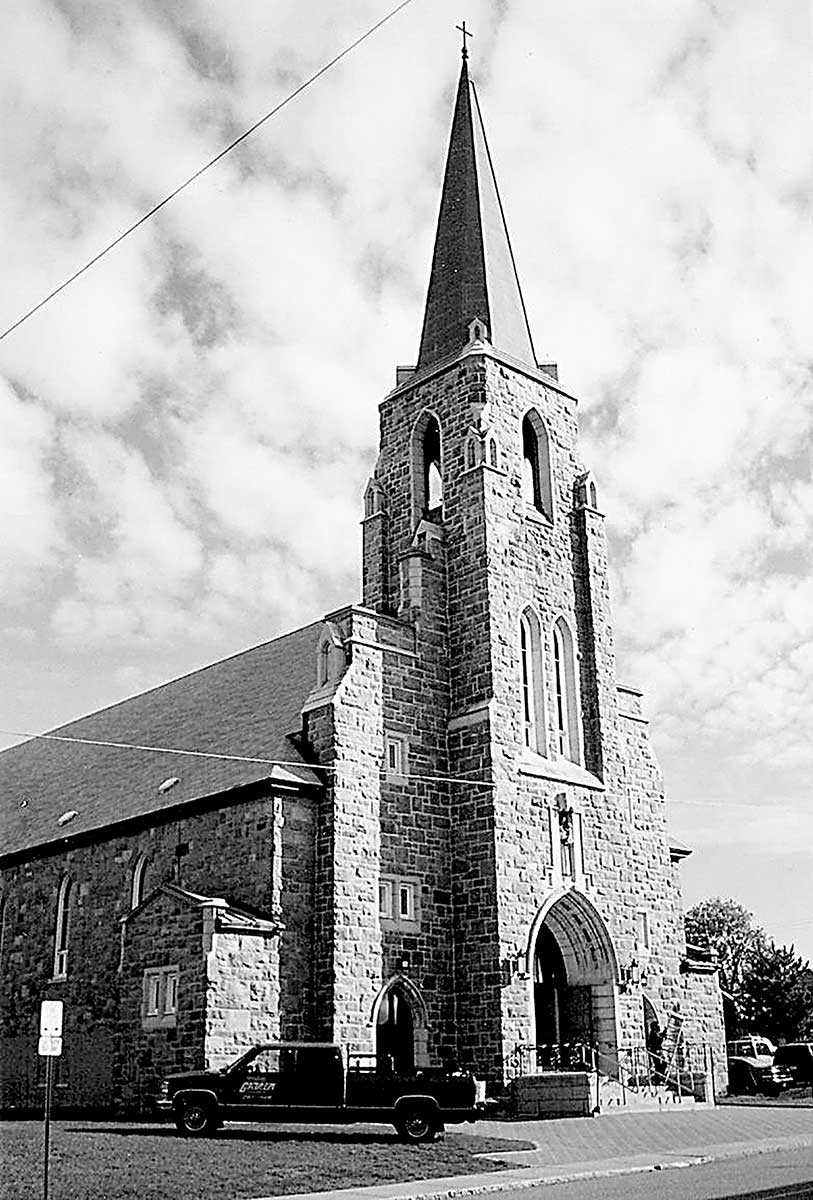

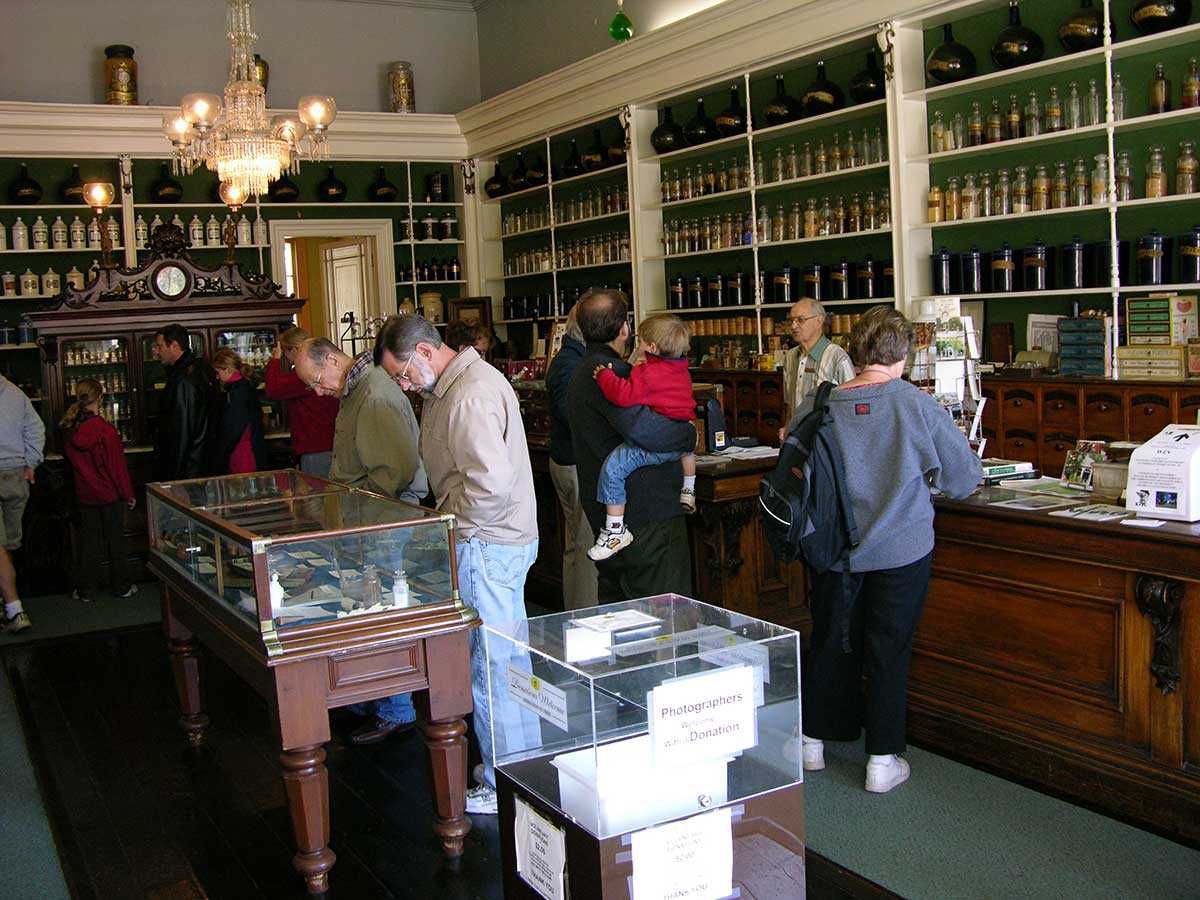

As the communities grew, so did some of Ontario’s most impressive institutional structures. Churches – including the Blue Church in Prescott, Hay Bay Church north of Adolphustown and St. Raphaels, northeast of Cornwall in the eponymous village – serve as tangible reminders of the province’s religious heritage. Town halls – like the ones found in Kingston, Smiths Falls and Perth – are testaments to democratic government and community. County courts and jails in Brockville, Kingston, Perth and Picton stand as symbols of law and justice. Commercial buildings and streetscapes – such as the ones found in Kingston, Perth, Carleton Place, Brockville, Picton and Prescott – represent Ontario’s economic vitality. Centres of culture – for example, the Regent Theatre in Picton and the Grand Theatre and Newlands Pavilion in Kingston – are representative of the province’s rich artistic heritage.

A network of defence installations dots the border, helping to defend Canada during the War of 1812 and seeing action in the Rebellion of 1837. Today, Fort Wellington in Prescott, the Martello towers and Forts Henry and Frederick in Kingston – and other military installations – are reminders of both war and peace.

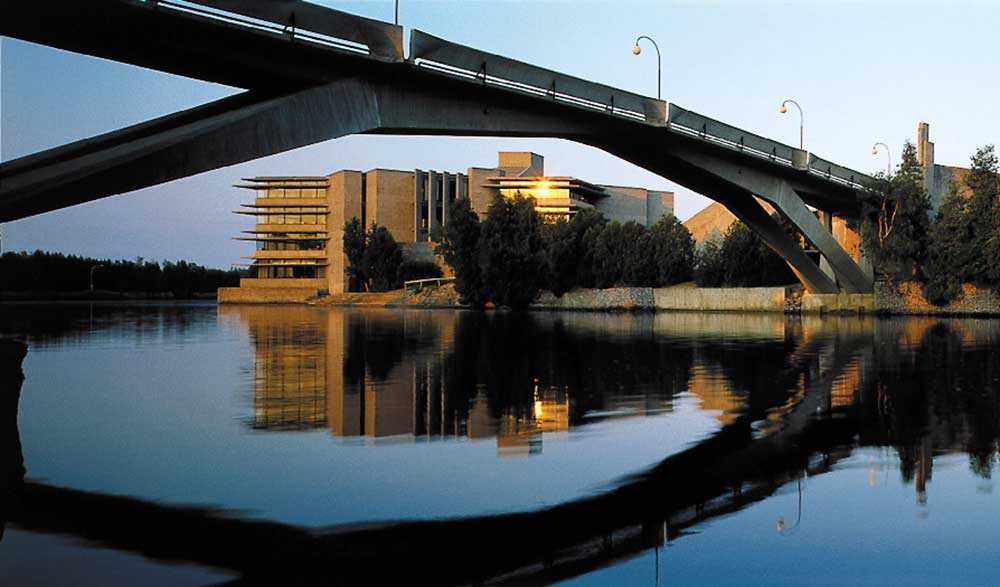

One of the area’s most impressive built features – the Rideau Canal – runs from Kingston to Ottawa. This scenic waterway passes through many historic communities such as Smiths Falls, Merrickville, Burritt’s Rapids, Manotick and others.

The need for the canal grew out of the War of 1812 when American forces threatened the safety and accessibility of the province’s main transportation and communication route – the St. Lawrence River. Construction of the canal began in 1826 under the leadership of Lieutenant-Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers. The work involved soldiers and thousands of labourers, mostly Irish and Scottish immigrants. They worked by hand with picks and shovels – felling trees, drilling through rock and moving earth to cut the canal. The work was harsh with labourers facing accidents, poor working conditions, labour disputes and outbreaks of cholera and malaria. It is estimated that 1,000 workers died during the canal’s construction. The canal reached Bytown, or Ottawa, six years later at a cost of £800,000.

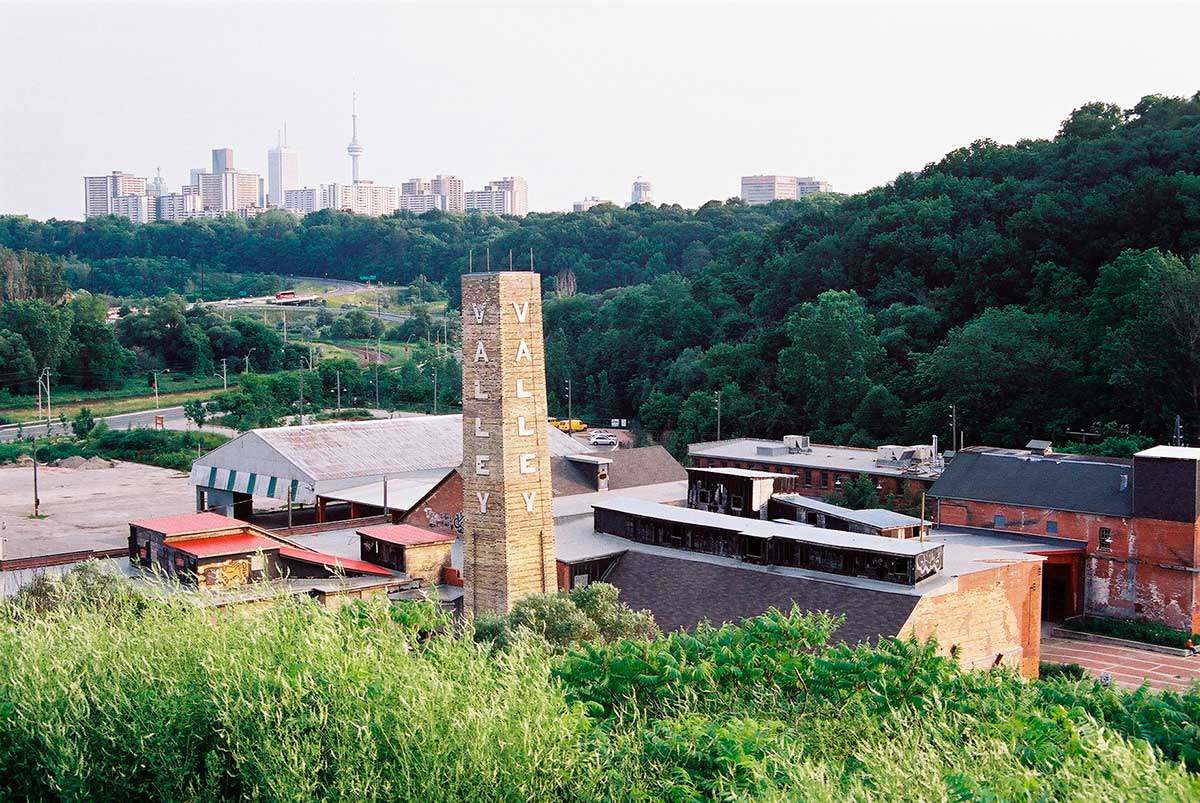

Over the years, the Rideau Canal has played an important role in Ontario’s economy as a trade and immigration route – and now as a tourism destination. Logging was an important part of the Ontario economy and contributed significantly to the province’s growth. During the 19th century, the Rideau Canal facilitated extensive logging, lumbering and milling enterprises, all of which contributed to the wealth and development in this part of eastern Ontario.

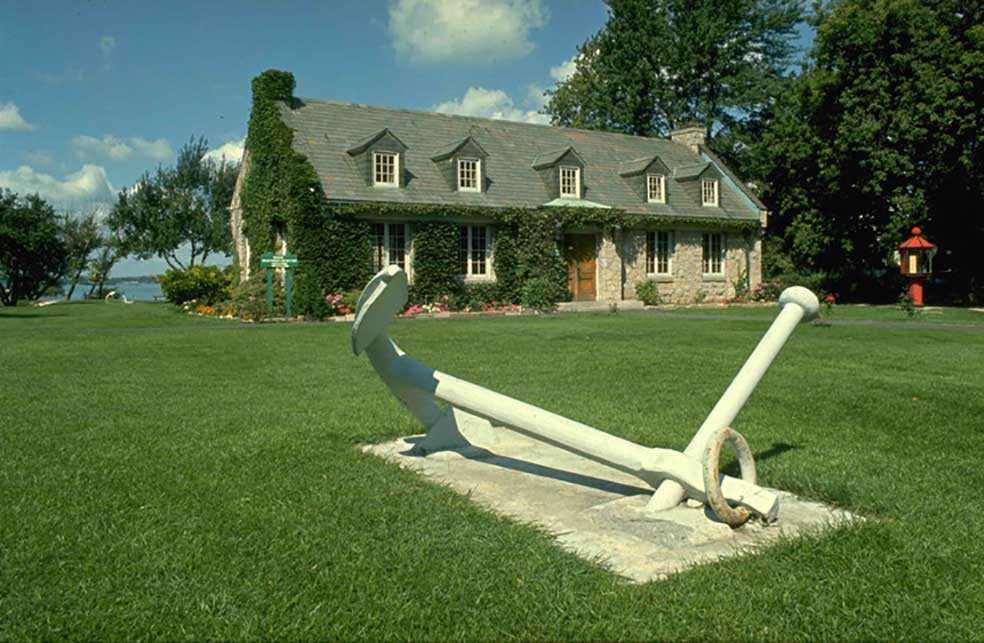

Today, the Rideau Canal is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a National Historic Site and a Canadian heritage river. It is visited by over a million tourists and recreational boaters annually and is commemorated by provincial plaques in Kingston Mills and Smiths Falls. Various sites along the Rideau Heritage Route allow for further exploration of the canal’s heritage, including a number of its historic lock stations and the Rideau Canal Museum in Smiths Falls.

By the mid-19th century, the inland of eastern Ontario opened as Ontario’s population grew. To encourage immigration and settlement, the government offered incentives such as land grants and settlement assistance to European immigrants. Lands were opened along a network of colonization roads, such as the Opeongo Road in Renfrew County. In that area, Irish and later German and Polish immigrants faced many challenges and hardships while transforming the rocky wilderness into farms and homesteads that grew into the communities of Wilno, Brudnell, Barry’s Bay and others. This influence can be seen in the homes and barns built of dovetailed log construction and in the churches and wooden crosses that dot the countryside, as well as the rich eastern European customs and traditions found in some communities.

Eastern Ontario is renowned for its green spaces and scenic natural heritage, including the St. Lawrence River, the Thousand Islands and the Rideau Heritage Route, along which you can canoe, kayak, bicycle or hike through a combination of pastoral farmland, forests and lakelands. One of the area’s most impressive features is the Frontenac Arch, a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve. This ancient granite landform covers approximately 2,700 square kilometers (1,042 square miles) mainly north and east of Kingston.

Eastern Ontario is rich in built, cultural and natural heritage. Its many historic sites and plaques tell an important story of the evolution of legal, military, political, social and religious institutions in this part of the province. Through the work of heritage organizations and dedicated community members, the heritage of this region is available for exploration and interpretation by both Ontarians and visitors to the province.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)