Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Lessons in preservation: A profile of two Ontario schools

Willowbank School of Restoration Arts

Willowbank School of Restoration Arts is an emerging institution that reflects what Gustavo Araoz, President of the International Council on Monuments and Sites, has called a paradigm shift in the heritage conservation field. This shift is towards a more ecological and integrated approach to design and development. It blurs the boundaries between cultural and natural heritage. It also accepts contemporary layers in the richly layered settings of historic places, as part of a dynamic rather than static world view. It deals with both intangible and tangible values, and maps both of them using a cultural landscape framework.

Willowbank is outside the formal college and university system, and this allows it to break down the boundaries between academic and hands-on training. Students in the three-year Diploma Program are as comfortable in their steel-toed shoes and hard hats in the workshops or the field as they are in seminar settings and intellectual debates.

Master mason and Willowbank Faculty Associate Danny Barber works alongside student Emily Kszan as she hones her skills squaring up a limestone block (Photo courtesy of Willowbank School of Restoration Arts)

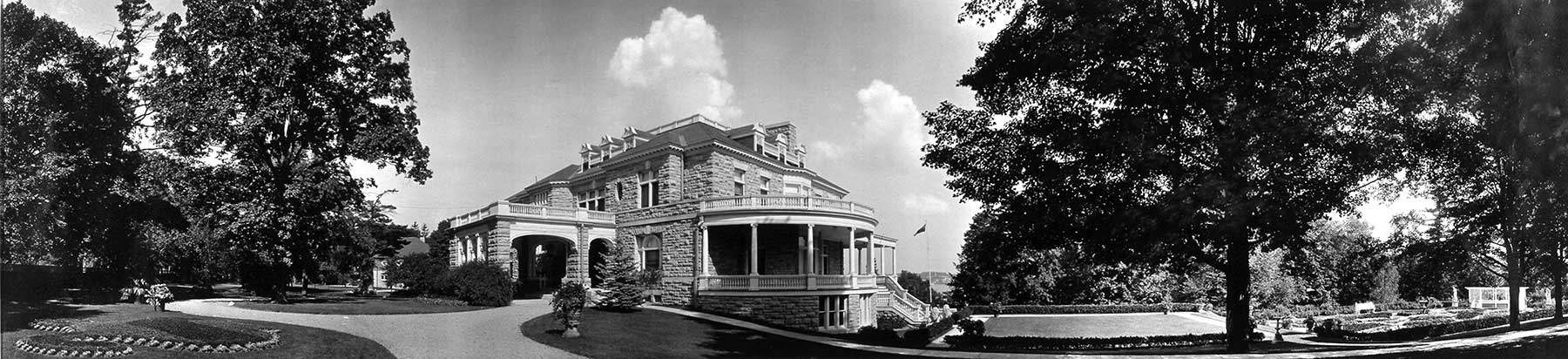

The school’s programs take place within the beautiful 13-acre setting of Willowbank National Historic Site. It is a place with a rich aboriginal heritage spanning 8,000 years, as well as a more recent early-19th-century estate house and grounds. Appropriately enough, the 1834 mansion is the work of master builder John Latshaw, a fitting model for the training of a new generation of master builders. The site is a key laboratory for the students in their understanding of layered sites and the many perspectives and disciplines that play a part in their evolution.

Willowbank has no permanent faculty; the students work with more than 50 different instructors, a number of whom are aboriginal mentors. They learn to think of the world in non-hierarchical terms, an essential prerequisite for understanding the new paradigm.

Although Willowbank is a young school, the success of its graduates confirms the fact that the new paradigm is taking hold. Graduates are working as stone masons and carpenters on National Historic Sites, as project managers for major conservation and adaptive reuse projects, as designers and advisers for developers, as senior heritage planners in municipal and provincial governments, as independent consultants and in major architectural offices. In almost all cases, their success comes from their comfort in moving across boundaries that were becoming too rigid and counterproductive.

This spring, Willowbank will be announcing the creation of a Centre for Cultural Landscape. This will provide a more visible external presence for Willowbank in demonstrating the new paradigm in theory and practice.

Queen’s University Master of Art Conservation program

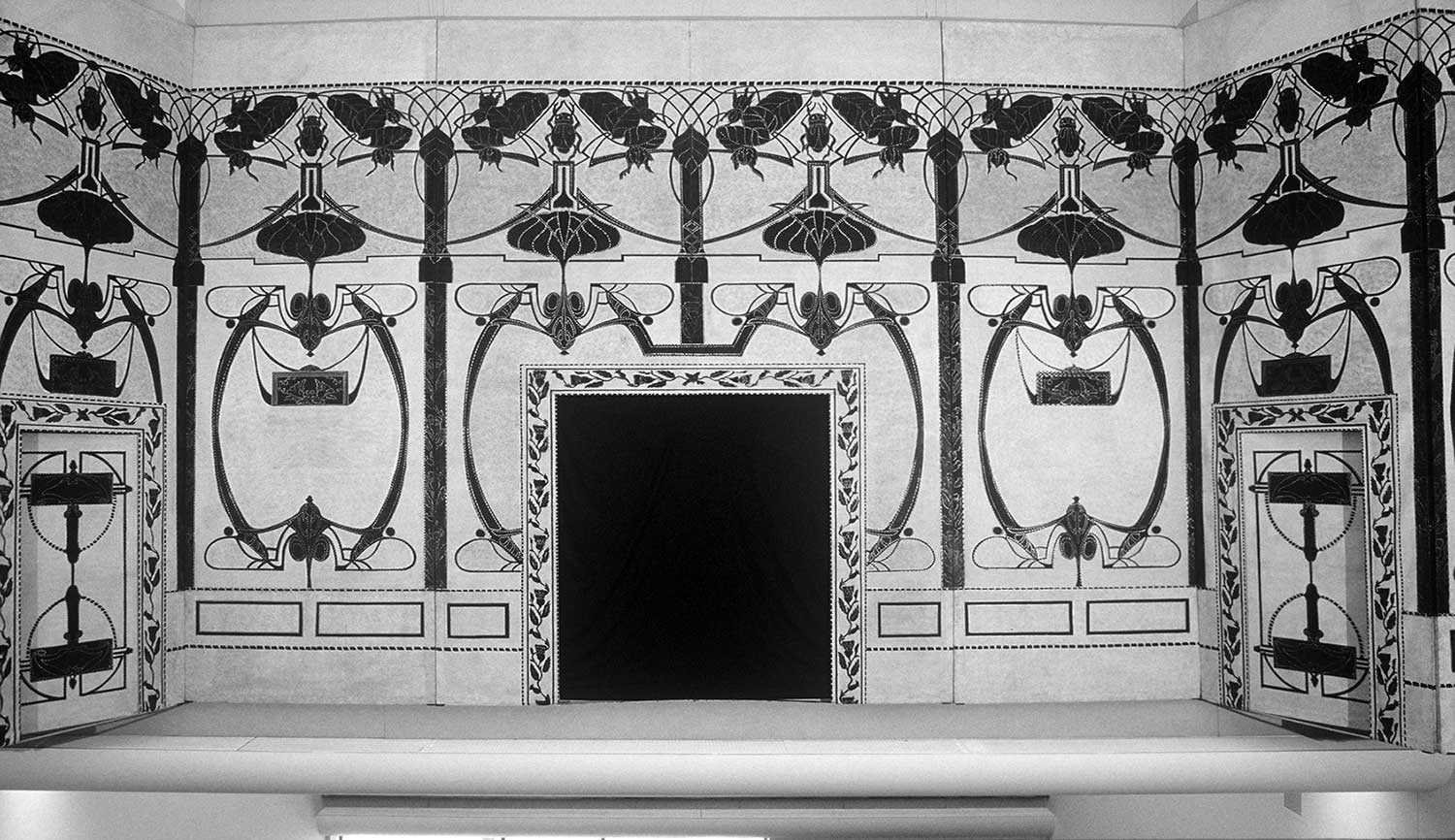

The Queen’s University Master of Art Conservation program offers Canada’s only graduate degree in the conservation of art and cultural artifacts, and brings together some of Canada’s top professionals and students for study and advancement of the field. Over the last four decades, the program has formed valuable partnerships with organizations committed to cultural preservation. Parks Canada, the Canadian Conservation Institute, the Canadian Museum of Civilization and the Ontario Heritage Trust have all provided expertise and instruction, and, just as important, artifacts in need of treatment for the training of students.

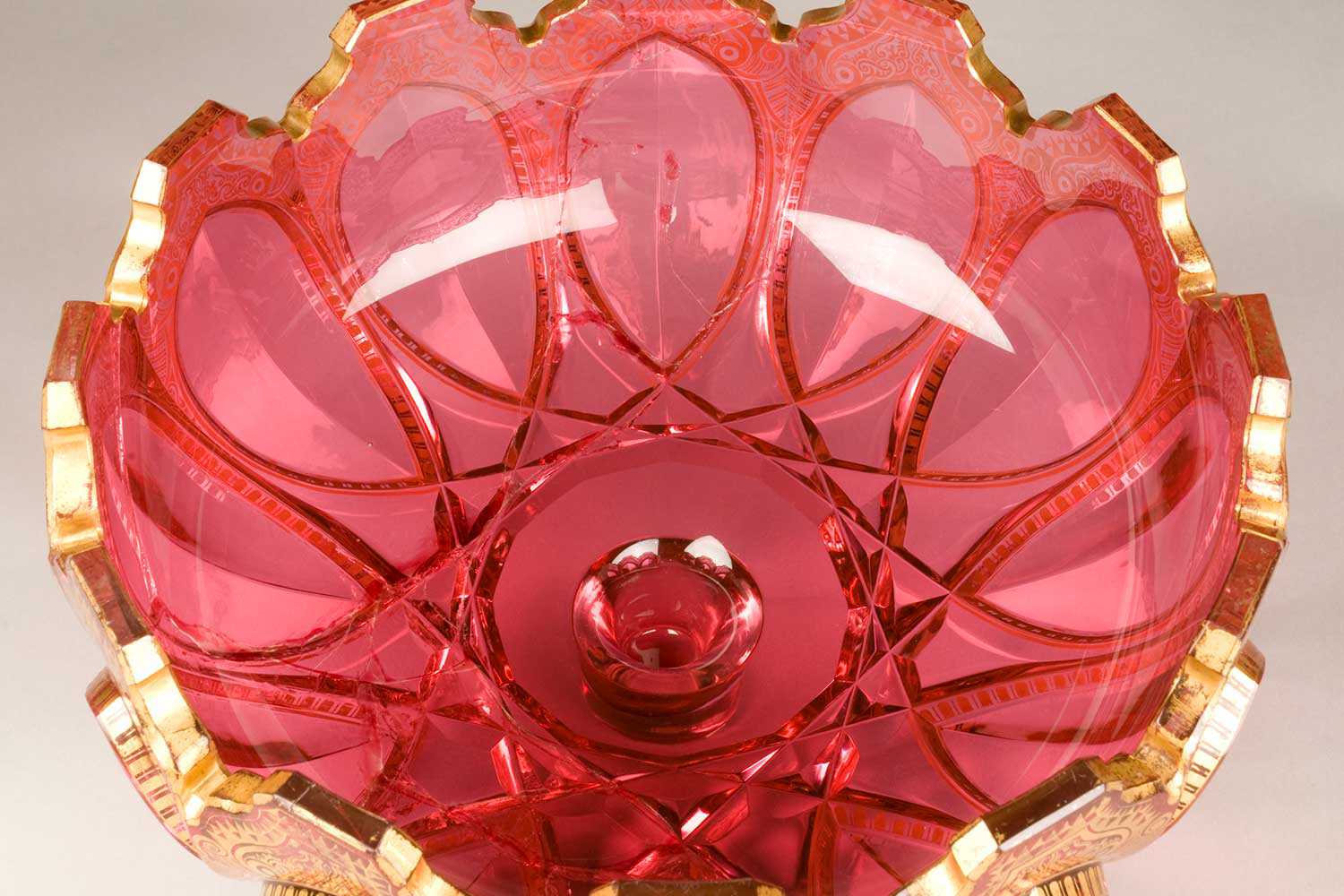

The Trust’s cultural and archaeological collections have provided many challenging objects for our students. Recently, a large cranberry glass punch bowl from Fulford Place in Brockville was conserved and returned to the Trust. Glass is one of the most difficult types of object encountered by students, as it is so unforgiving. When reassembling a broken piece, if any joints are misaligned, the last piece will never fit. Chips and missing fragments from coloured glass must be toned so that they match both reflected and transmitted light, and adhesives that can be used to repair the glass are limited.

Due to its complexity of treatment, the cranberry punch bowl was treated by four different students, starting in 1997. Lisa Ellis (Art Con ’98) was first to work on the bowl, which had endured a bad repair job at the hands of a well-meaning individual after it had been dropped. Yellowed epoxy was thickly applied and clear tape covered the inside joints. Lisa worked to reduce the epoxy that obscured the surface.

Michael Belman (Art Con ‘02) spent eight months slowly breaking down the old epoxy in a solvent chamber and then used a conservation grade, non-yellowing epoxy to put it all back together again. Michael’s plan was to then add a thin layer of cranberry-coloured epoxy to fill in the surface. However, the epoxy dyes available 10 years ago were unstable, and Michael’s test colours proved unreliable.

The bowl sat in a cupboard for five years before Sara Serban (Art Con ‘08) took it up once more. Using a new dye for epoxies, Sara was successful in developing a colour matching recipe and technique. The final execution of the repair, however, was left to Tania Mottus (Art Con ‘10). Following the techniques proposed by the previous students, Tania painstakingly added coloured epoxy, drop by drop, over several months to slowly build the depth of shade to match the original cranberry glass. In spring 2010, the object was returned to Fulford Place after a 14-year absence.

While not typical, and no doubt a source of frustration at times for the students involved, the treatment of Fulford Place’s cranberry glass punch bowl held valuable lessons in patience and demonstrated how learning from your peers can help achieve high-quality results.