Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

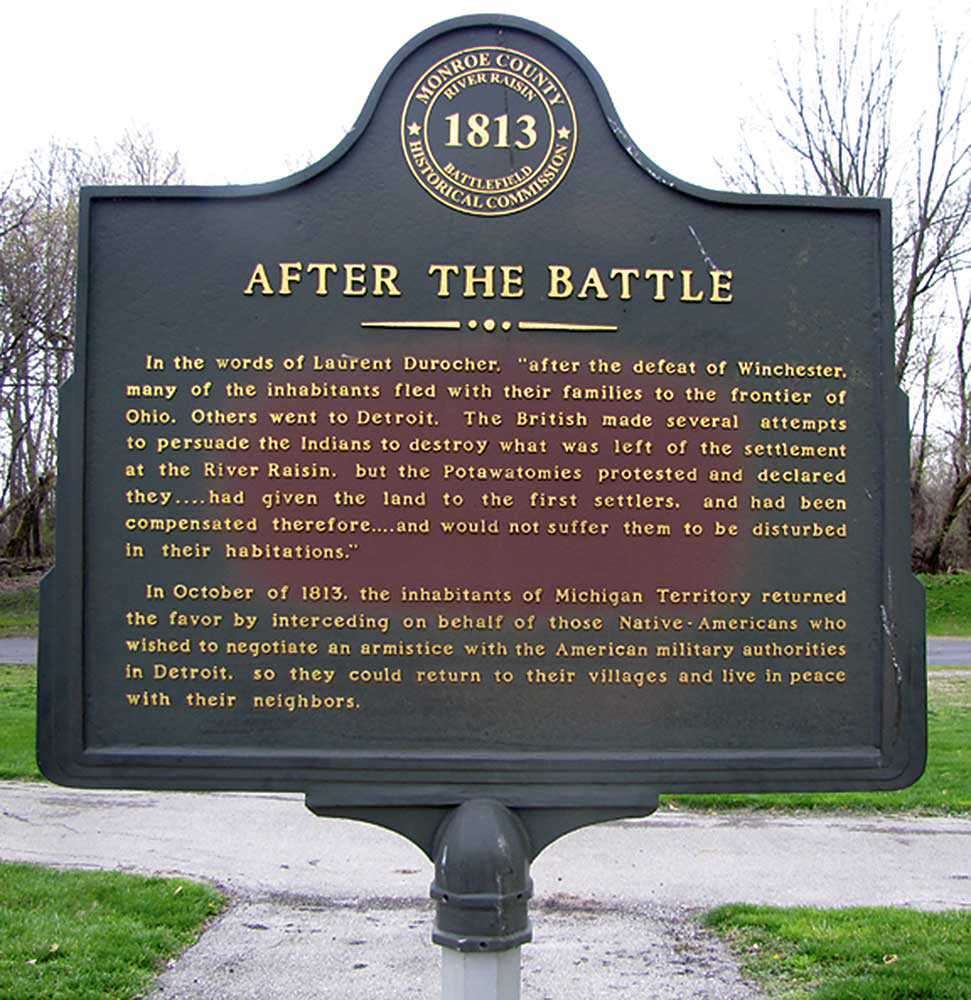

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Keeping the faith: The Church and French Ontario

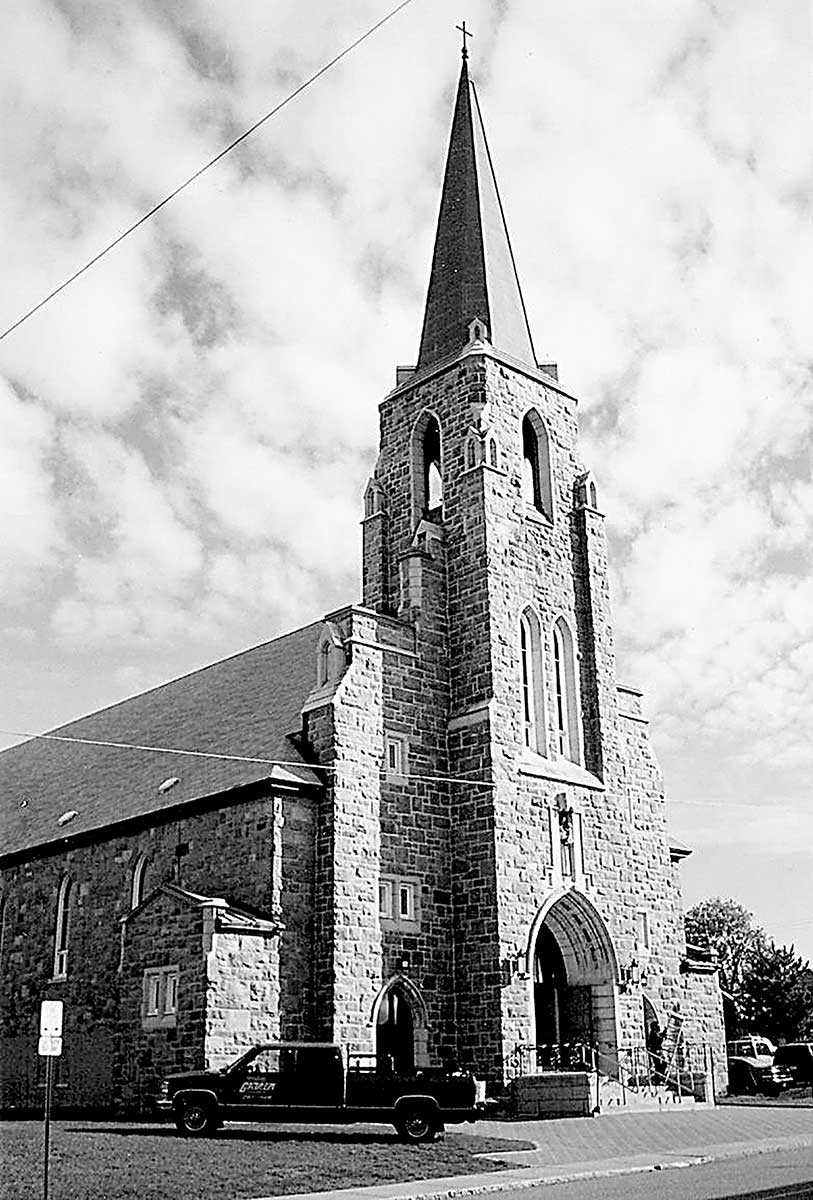

The arrival of the Catholic Church in modern-day Ontario can be traced back to New France with the establishment of the missions of Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons in 1641 and L’Assomption in 1744.

As was the case for all newly established francophone communities, the Church represented the pivotal point of community and family life. When thousands of French-Canadians settled in eastern and mid-northern Ontario in the second half of the 19th century, recently arrived Irish Catholics in these regions quickly became a minority in their parishes and schools. Both began to offer services in French and English.

As early linguistic tensions mounted, Ottawa Bishop Bruno Guigues encouraged the Irish to settle in the Ottawa Valley to the west and French-Canadians in the counties of Prescott, Russell, Glengarry and Carleton to the east. Despite the calls by the English-speaking clergy to make English the language of Catholicism in North America, the French-Canadian elite argued that, as its people were practically all Catholic, abolishing French-language parishes and schools would eliminate the Church’s competitive advantage over Protestant churches.

Pragmatism allowed for the opening of French-language parishes and schools where the number of parishioners justified it. As the number of French-Canadians increased (100,000 in 1881 and 200,000 in 1911), so did the hostility from English-speaking Catholics who perceived them as a threat to their legitimacy on Ontario soil.

The Orange Order – a Protestant fraternal organization – opposed both the importation of French and Catholicism in the Loyalist province, and the Irish seemed willing to sacrifice French in order to save separate schools. Clergymen such as London Bishop Michael Fallon fiercely fought for the Anglicization of schools and parishes in the 1910s, but the Vatican ultimately instructed Ontario bishops to stay out of this political debate, and acknowledge French Canadians hoping to fight off assimilation. Hostility toward French-language education galvanized parents and brought them to use religious organizations to advance the development of their institutions. Language and faith formed a continuum in French Canada. They mutually protected each other’s minority status on the continent. Catholicism, along with the French language, prevented these citizens from integrating the ethnic mosaic of Ontario. Franco-Ontarians considered French and Catholicism as equal partners in Confederation along with English and Protestantism.

But as religious practice declined and a more assertive nationalism emerged after the First World War, language became the primary distinguishing factor between individuals. It is therefore a paradox in French Ontario that Catholicism (still the majority’s faith) has come to divide the community internally as distinct public and Catholic French-language school systems were established in the 1970s and 1980s. Competition for student enrolment has led to the expression of two forms of Franco-Ontarian identities: one secularized and language-based, the other more traditionally Franco-Catholic. The Church remains, in many ways, an unavoidable element of French Ontario’s past and present.

![The family of Simon Aumont. Only Simon himself and Irène (seated, holding a doll), survived the great fire that devastated the region in 1916, Val Gagné (Ontario), [before 1916]. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the collection of Germaine Robert, Val Gagné, Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Frenette-Ph23-VG-3-web.jpg)

![Students demonstrating against Regulation 17 outside Brébeuf School on Anglesea Square in Ottawa’s Lowertown, in late January or early February, 1916 / [Le Droit, Ottawa]. University of Ottawa, Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario archive (C2), Ph2-142a.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Cecillon-Ph2-142a-web.jpg)