Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

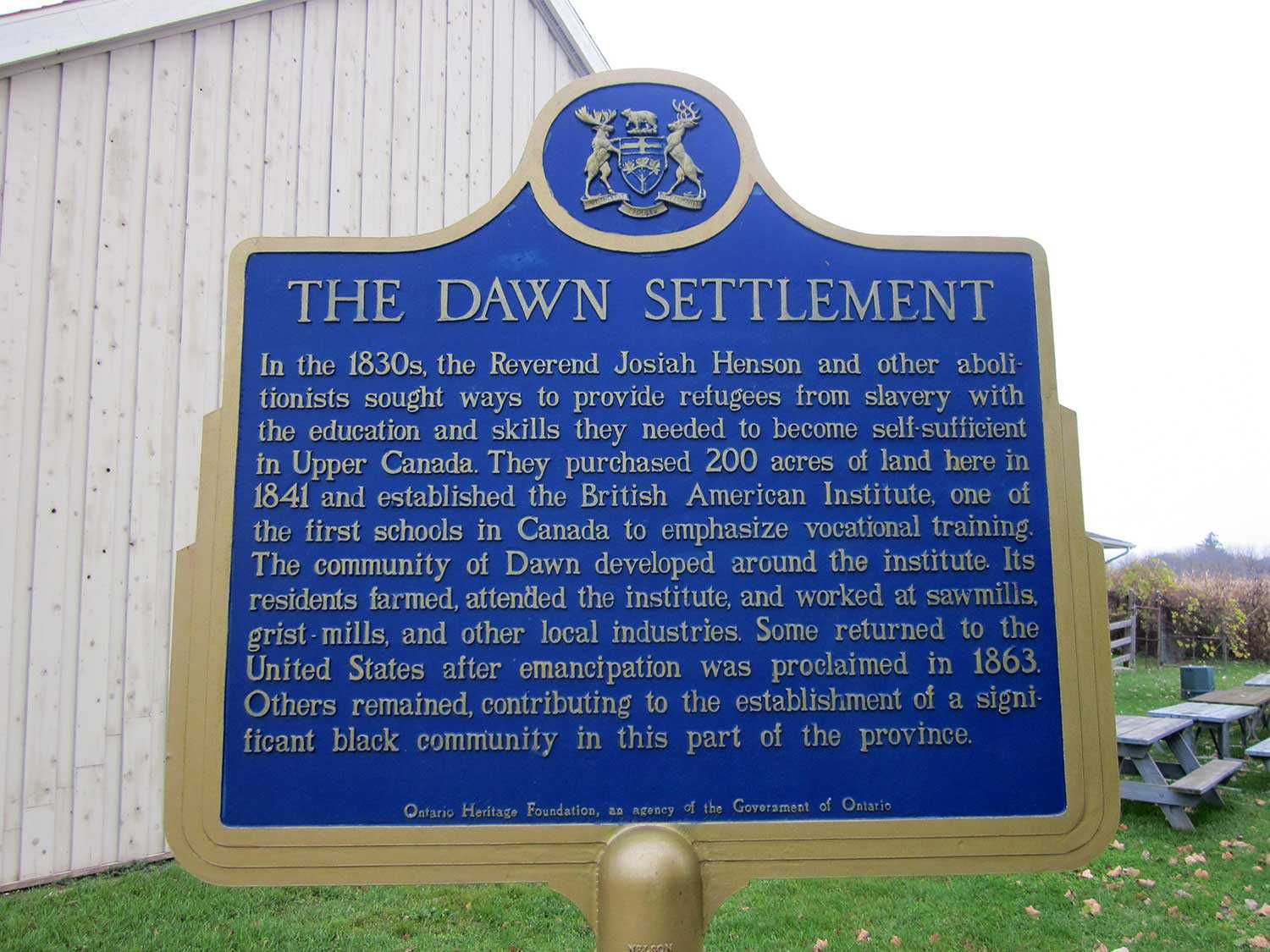

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Investing in preservation

It is an unfortunate reality that the preservation of our heritage remains the exception rather than the norm. What is a common-sense approach to living within our means is typically seen as obstructionist, negative and a barrier to progress. Preservation is commonly pitted against economic development. There is a misguided perception that we must either celebrate and retain our heritage, or cast it aside in favour of an increased tax base, renewed infrastructure and job creation.

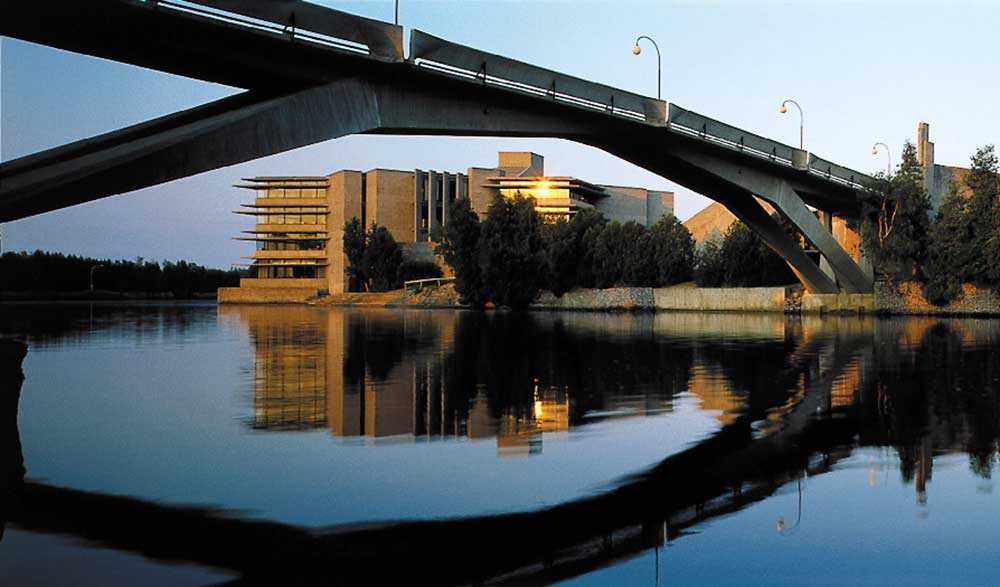

Preservation is a prime investment capable of unmatched long-term ecological, cultural and financial returns. Significant investments in preservation are already being made throughout Ontario in the form of education and awareness, adaptive reuse, public recapitalization of our heritage infrastructure and proactive volunteerism. All of these investments combine to make Ontario a better place – now and for future generations.

Awareness and education provide the foundation to any investment in preservation. Without a healthy sector of skilled trades, contractors and professionals, investing in preservation would be impractical. There are few experts and practitioners in Ontario – certainly far fewer than are needed to provide adequate conservation support to the growing inventories of heritage properties. The Ontario Heritage Trust’s mandate stresses education, and it provides assistance by sponsoring lectures and workshops, mentoring students and supporting interns and co-operative placements.

There are several post-secondary institutions that offer formal education or training in the specialized field of cultural and natural conservation. These include: Willowbank School of Restoration Arts (Queenston), Algonquin College Heritage Institute (Perth), the Heritage Resource Centre (University of Waterloo), Fleming College’s Museum Management and Curatorship and Ecosystem Management Technology Programs (Peterborough), Queens University’s Master of Art Conservation Program (Kingston), Carleton University’s School of Canadian Studies (Ottawa), and Ryerson University’s Continuing Education Program in Architectural Preservation and Conservation (Toronto). Many of these programs connect to the heritage sector through partnerships with employers, municipalities, private consulting firms and non-governmental organizations. With a large number of the province’s conservation experts edging closer to retirement, it is reassuring to see the development and success of these new programs in meeting demands for training and education.

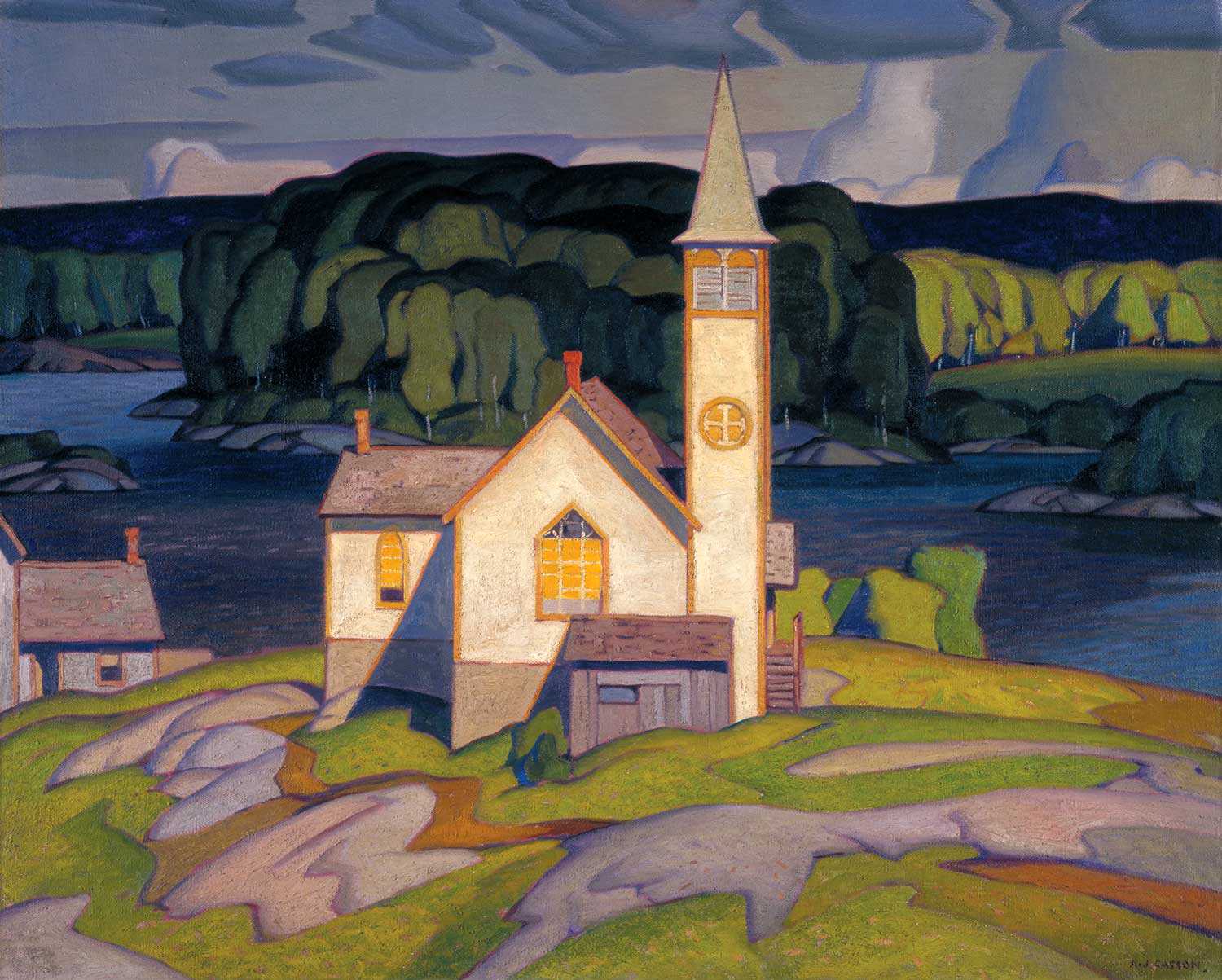

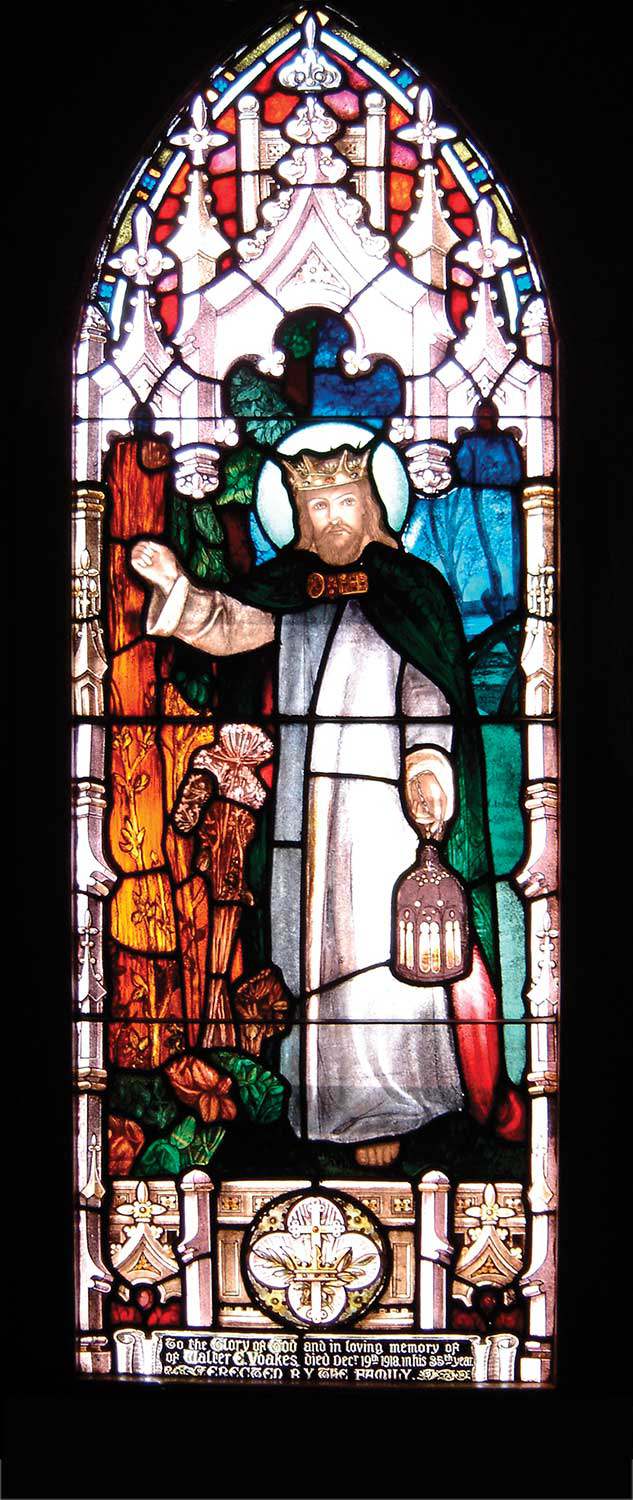

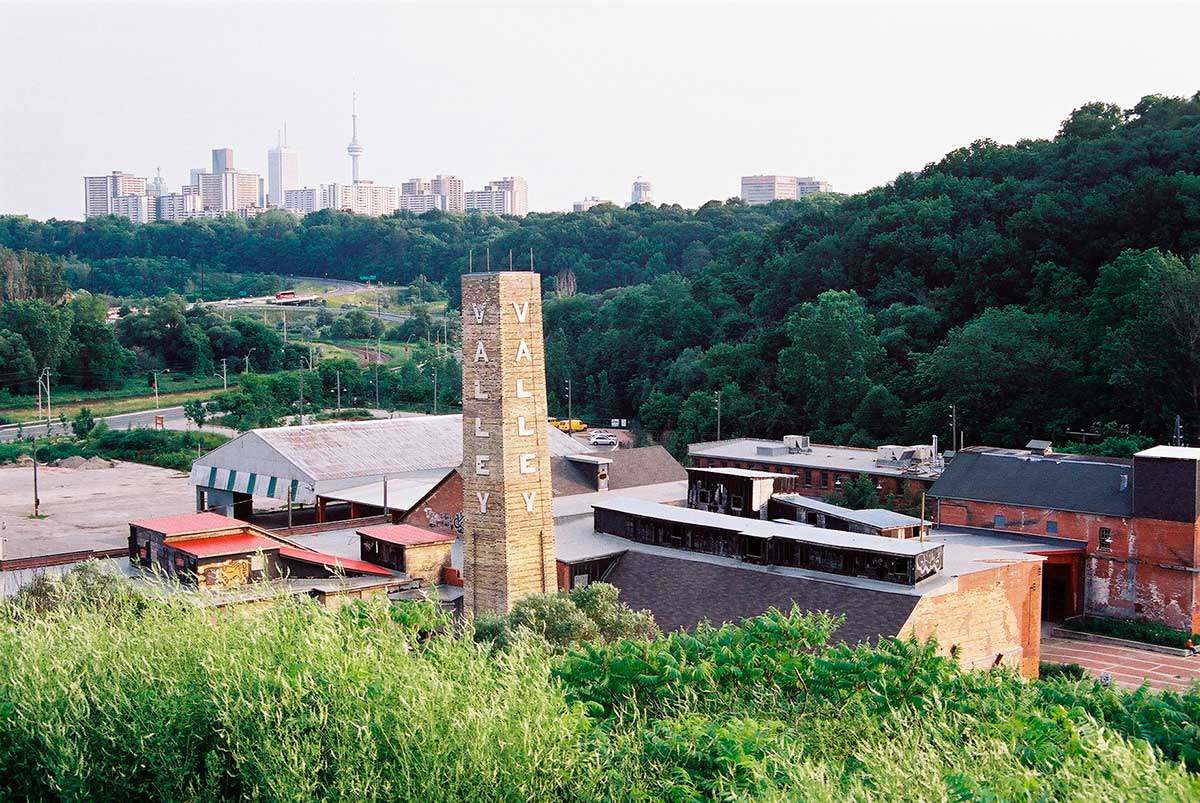

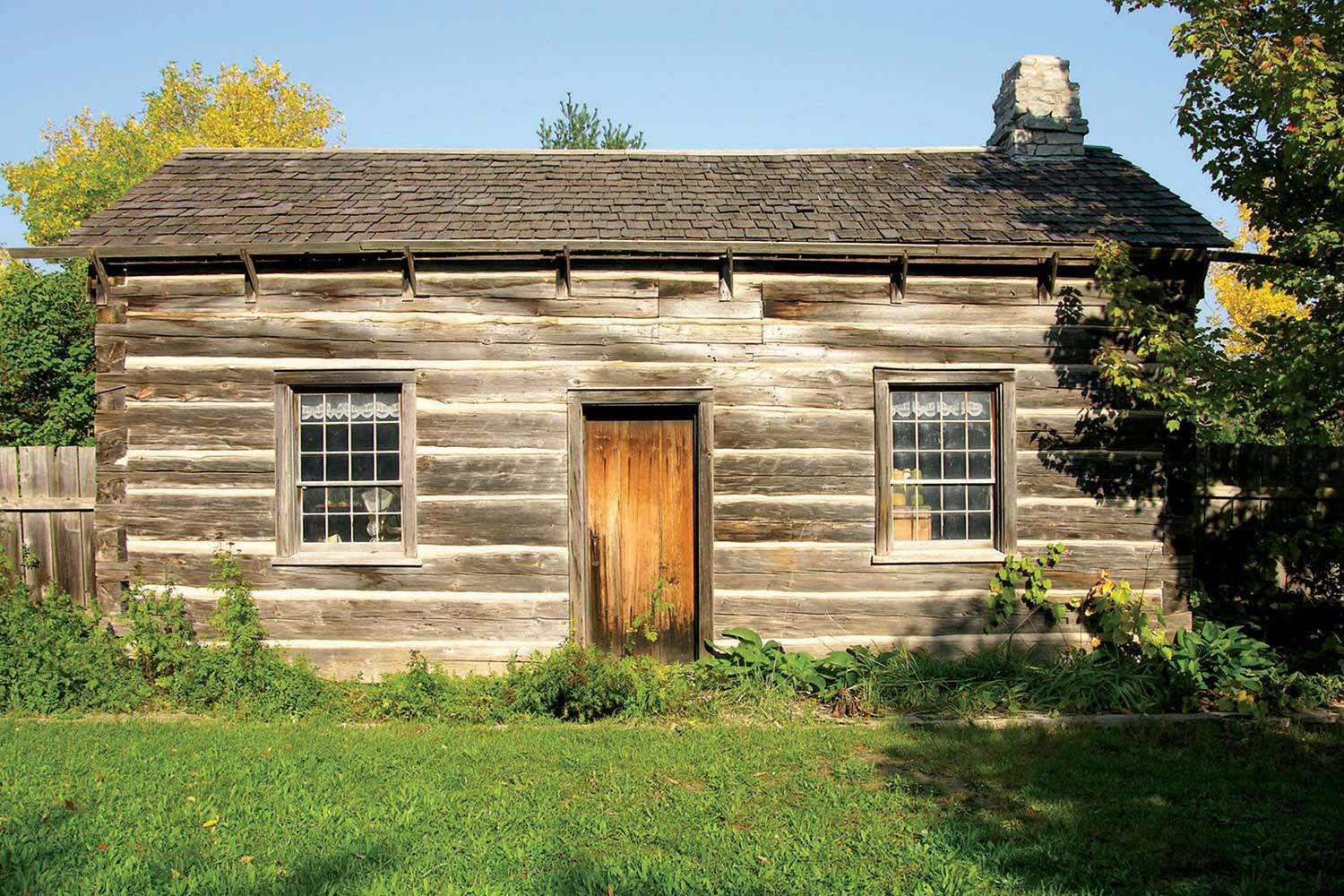

We are also witnessing investment in cultural preservation when individuals and organizations choose heritage sites as venues for activities and locations for businesses. Few things can guarantee the preservation of a historic place better than active use. Without a realistic or feasible purpose, a vacant building’s fate is often sealed. Sometimes, a tenant or owner is prepared to invest in a historic place because of its special character. Customers might frequent a restaurant because of its heritage ambience, and artists set up their galleries in industrial buildings because of the esthetic tension between new and old.

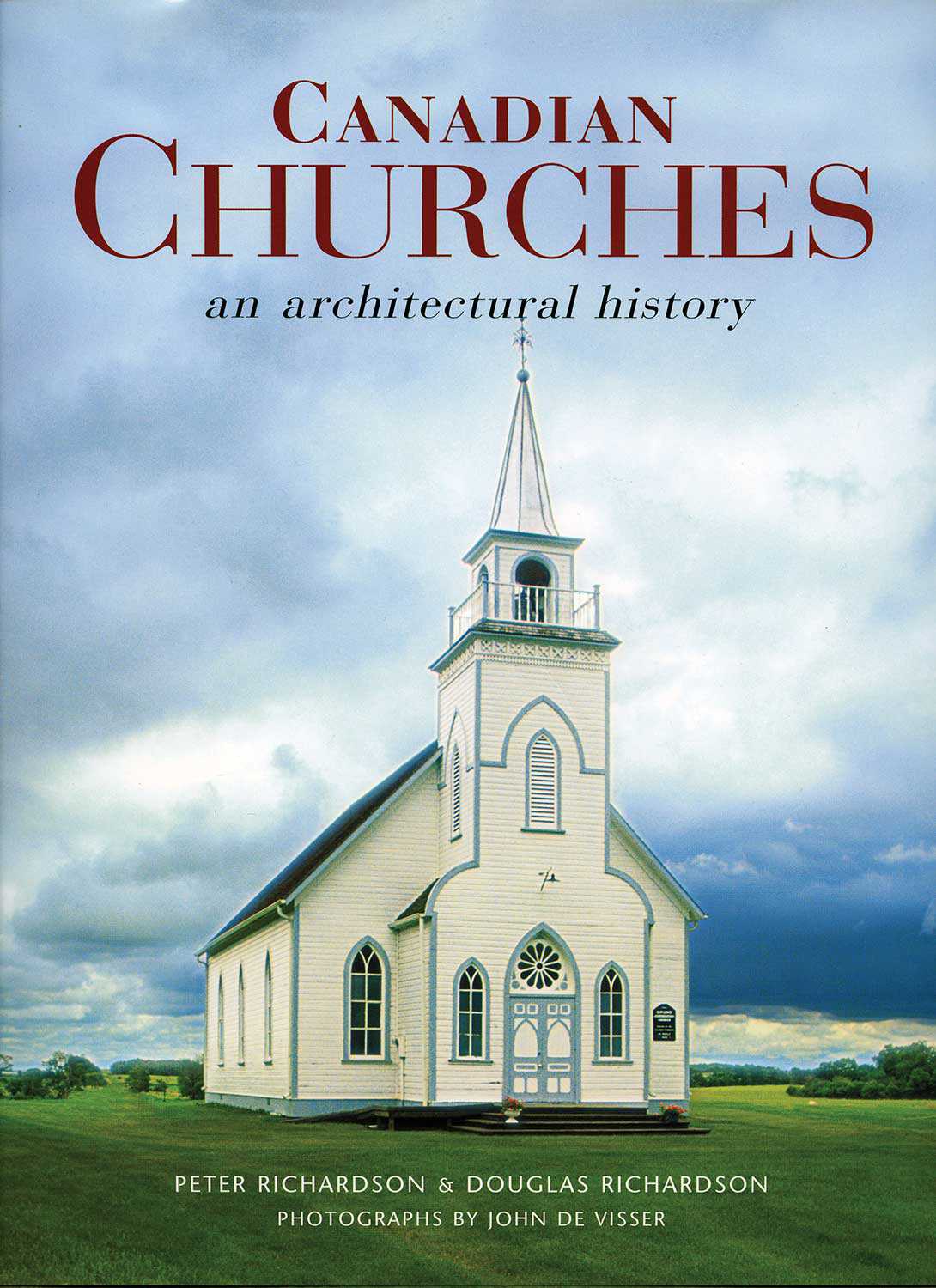

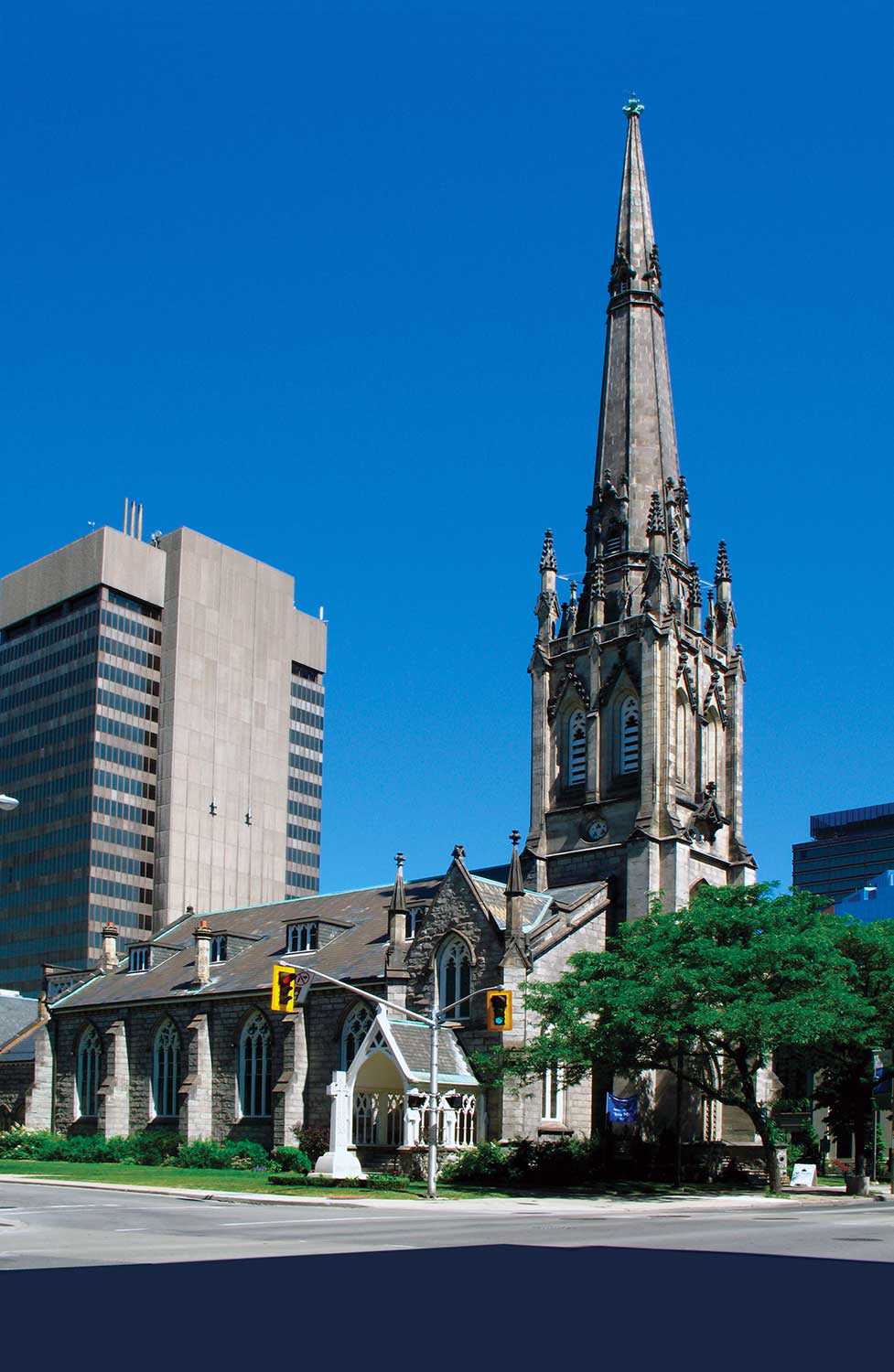

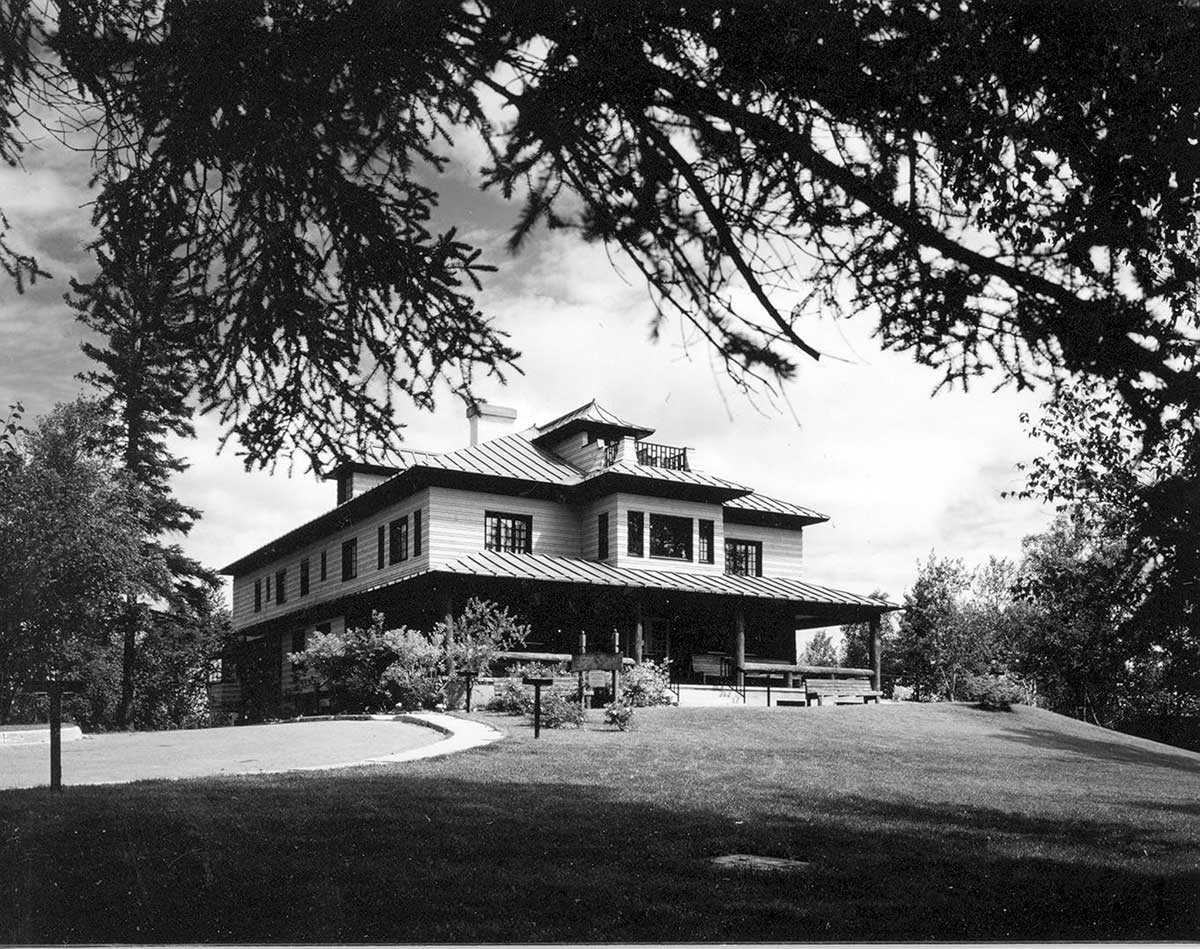

Buildings at risk from neglect or threatened with demolition are often not identified until long after deterioration has begun. In a final effort to save them, there may be a movement to have them designated or fitted with a new use. But, often, this approach is a forlorn hope. Fortunately, it’s becoming increasingly common for sites to find new uses before they become endangered. Some individuals and organizations actively seek heritage sites as venues for predefined uses. Numerous restaurants and pubs in Ontario deliberately select historic sites such as houses, mills, churches and factories. Examples of this type of investment and branding include The Keg Steakhouse and Bar in St. Catharines (the former Independent Rubber Co. factory), the Vicar’s Vice in Hamilton (former Methodist Church) and the Oakland Hall Inn in Aurora (a former farmhouse). There is so much interest in the hospitality sector for these cosy old buildings that, where they cannot be found, they are sometimes relocated from other areas or simply replicated.

Woodstock Town Hall National Historic Site is protected by a Trust conservation easement and is owned by the City of Woodstock. The landmark received an endowment grant to assist in its long-term maintenance.

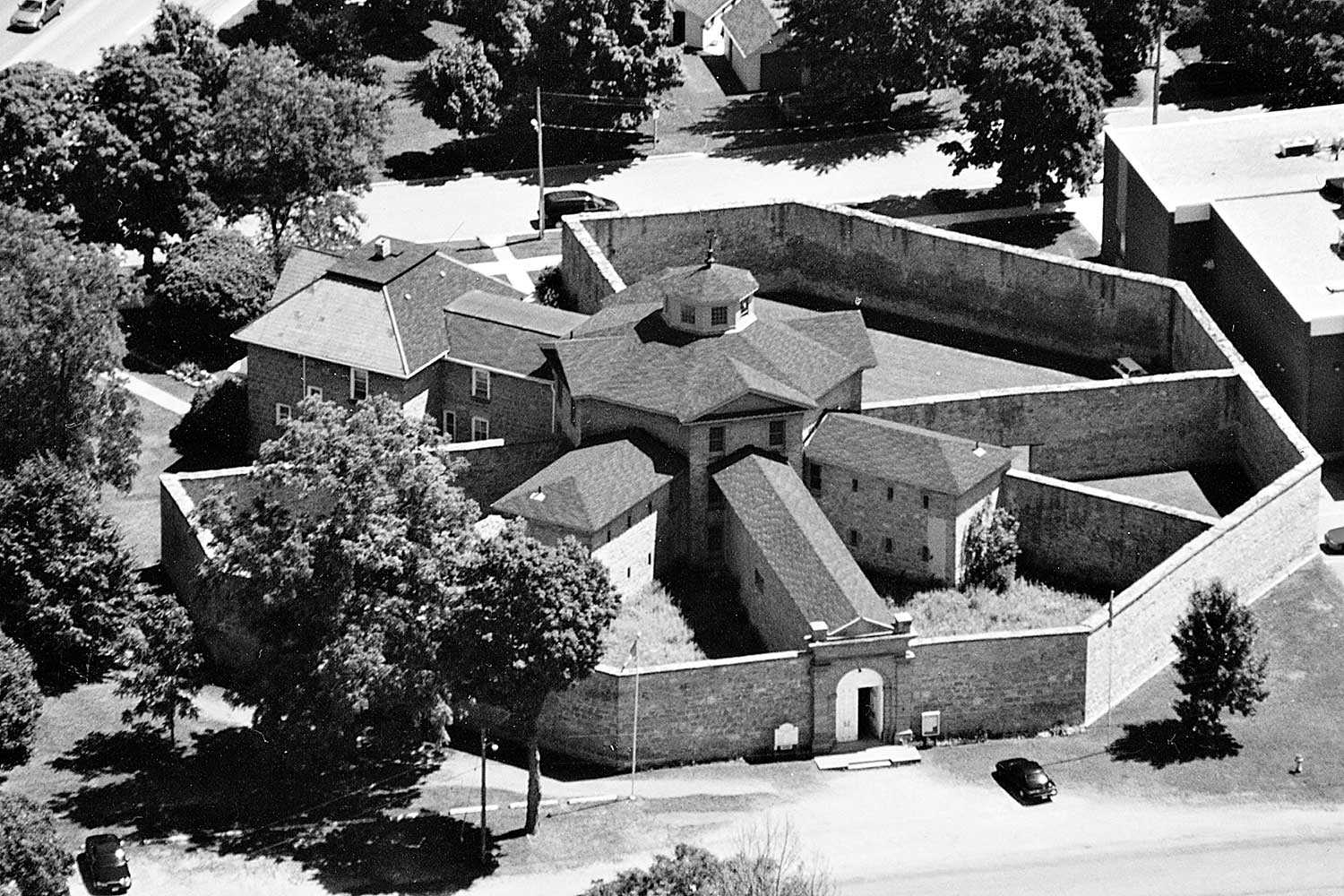

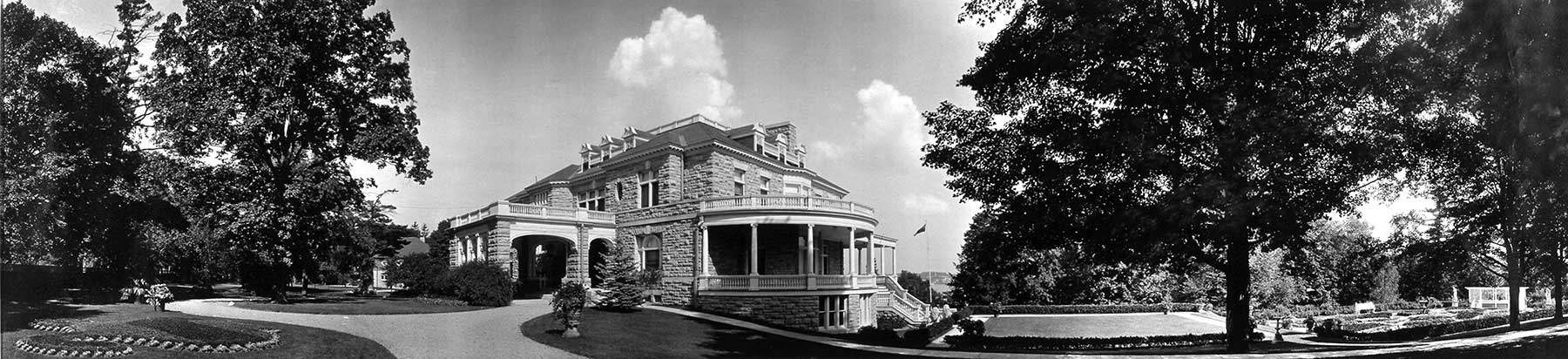

Investment in preservation – especially public investment – seems to happen in cycles. Ideally, with proper maintenance, planning and a sustained effort, there should be constant and continuous investment in preservation. This idea, however, seems to be contrary to our society’s approach to building life-cycle costing. We are bombarded daily by the “maintenance free” slogans of modern products and designs. When one looks at the major historic sites in Canada, there is a clear pattern of investment typically tied to funding priorities. For instance, during the Great Depression, a series of make-work projects transformed Canada’s colonial fortifications through a wave of renovations. To coincide with the centennial celebrations of Confederation in 1967, the Government of Canada launched a massive campaign of heritage programs that saw financial reinvestment in our major historic sites.

With the passing of the Ontario Heritage Act in 1975, a period of provincial reinvestment through heritage grants began. This peaked in the 1980s and continued until the early 1990s. Many large institutional historic sites – such as courthouses, town halls and other civic landmarks – underwent major rehabilitation to extend their use or to bring new uses to these significant, but often deteriorated, heritage sites. The period from the 1990s until recently has been one of sporadic government heritage funding.

During this same period, a number of municipal heritage funding programs were created, and the province provided support to not-for-profit organizations through the Heritage Challenge Fund (1999-2001). In recent years, the heritage property tax rebate has been the major sustained incentive program for property owners in those municipalities that have decided to participate. This program, which reduces property tax by 10 to 40 per cent, targets the private sector and is municipally administered at the discretion of each local council. With the economic downturn in the fall of 2008, the Government of Canada and the Government of Ontario responded with unprecedented stimulus funding and infrastructure support. This recent funding has benefited many large public heritage sites; many of the projects are ongoing.

This overview of public investment in preservation reveals a pattern of generational funding – an approach that encourages deferred maintenance by favouring one-time capital funding over continued operating support. Many owners cannot afford to maintain heritage properties that have endured long periods of deferred maintenance, and the current system makes new construction a more feasible option. The economic reality is that funds invested in preservation projects reach the local economy faster, because the focus is on labour and specialized skills, which leads to long-term employment. New construction requires significantly higher material and merchandise costs, and reduces the need for skilled labour. Our inability to foster a maintenance culture has left us with a weak and underdeveloped maintenance industry. It’s clear that the best form of preservation and investment is one that is constant, incremental and sustainable.

Taking action before a cultural or natural heritage site has deteriorated due to lack of maintenance or other destructive action is key to prudent investment in preservation. Sometimes a site is saved through the tireless efforts of a few who proactively invest their time, money and passion to protect, preserve and find a new use for cherished local landmarks. In the natural heritage sector, volunteers form local land trusts to preserve environmentally sensitive, scenic and unique lands from redevelopment and loss. In the cultural heritage sector, local chapters of the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario, local historical societies and volunteer groups dedicated to specific historic sites are playing an increasingly important role in the preservation movement.

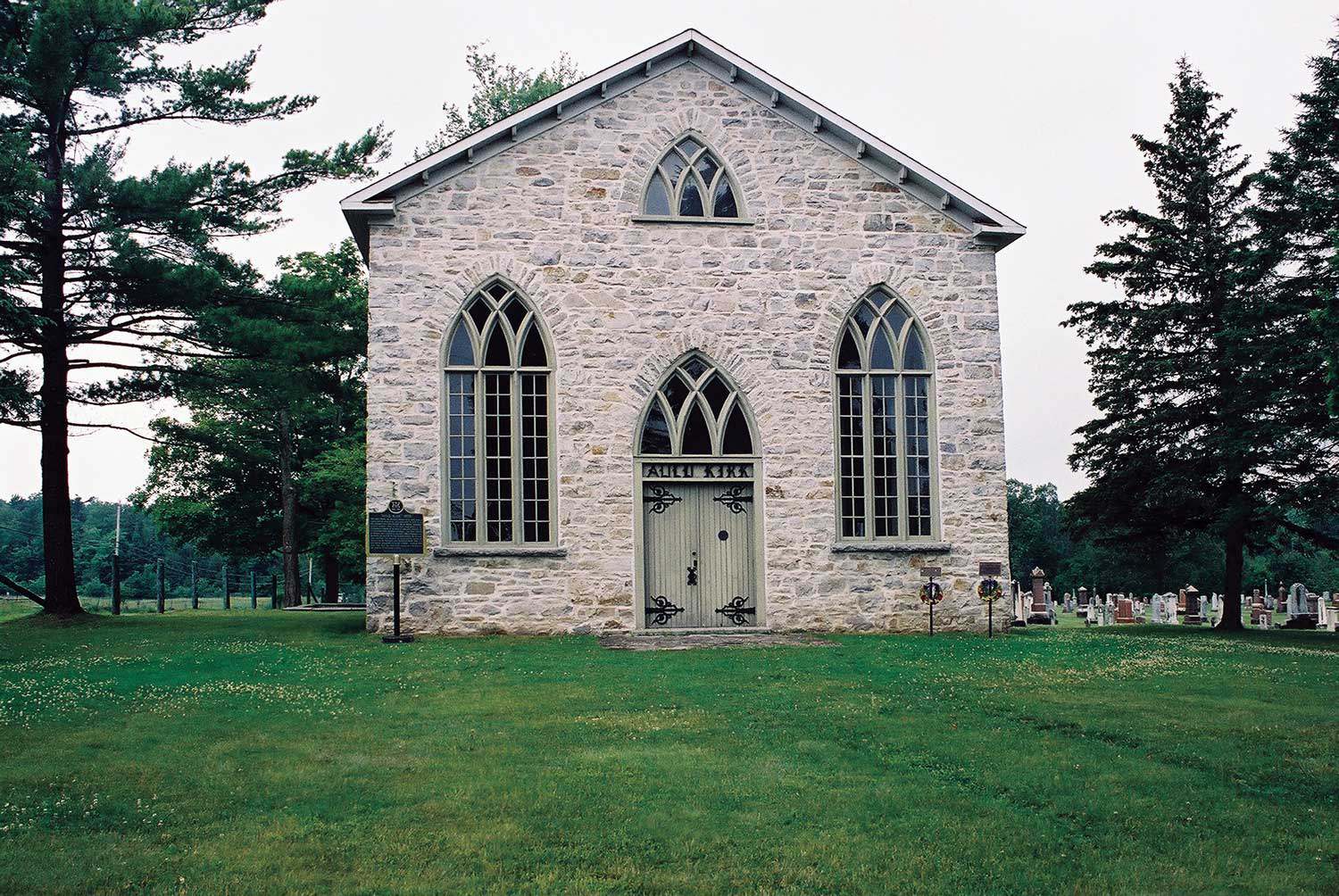

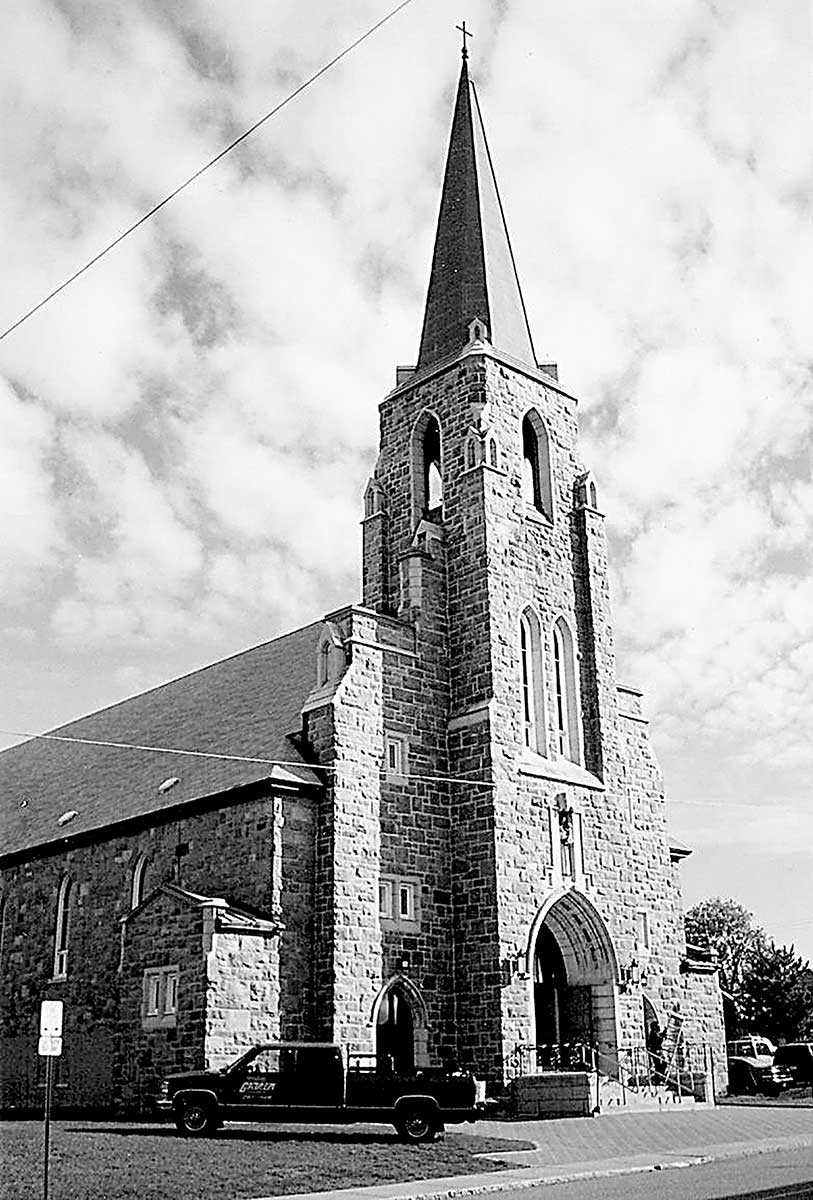

In 2009, a few individuals banded together in Chatham-Kent to ensure the preservation of a unique heritage building. With a dwindling congregation, historic Highgate United Church closed as a place of worship in June 2010. Well in advance of the closure, a group of local volunteers formed the Mary Webb Centre and approached the congregation. The group contacted the Ontario Heritage Trust for technical assistance and advice. A special workshop on the adaptive reuse of the building and a brainstorming session were facilitated by the Trust during the 2010 Ontario Heritage Conference.

The Mary Webb Centre developed a business plan for acquiring and adapting the church as a cultural and community centre. In December 2010, the Mary Webb Centre acquired the building from the United Church. Recently, the group received not-for-profit status with its official name, The Mary Webb Cultural and Community Centre; they plan to secure charitable status to enable them to apply for grants. Now that the former church has been secured, the municipality is proceeding with the designation of the landmark under the Ontario Heritage Act.

A number of other community groups are monitoring the success of The Mary Webb Cultural and Community Centre. Not only is the case study inspirational, but it also speaks to the importance of early action, multiple partnerships and a solid business plan. This example also illustrates the value of establishing good relations with the owner, rather than being adversarial or confrontational.

Investment is rooted in the premise that little actions can lead to big returns in the long term. Investments on the scale of multiple generations, rather than short-term cycles, are best when the goal is preservation of our cultural and natural environment. What is true for a diversified financial portfolio is true of investments in preservation. Investments are most successful if they are prudent, steady and sustained over a long period. Financial investment is important to preservation, but equally important is education, volunteerism, willingness to secure partnerships, personal commitment and proactive community leadership. Investment in preservation today is a venture from which Ontarians are certain to draw dividends in the future.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)