Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

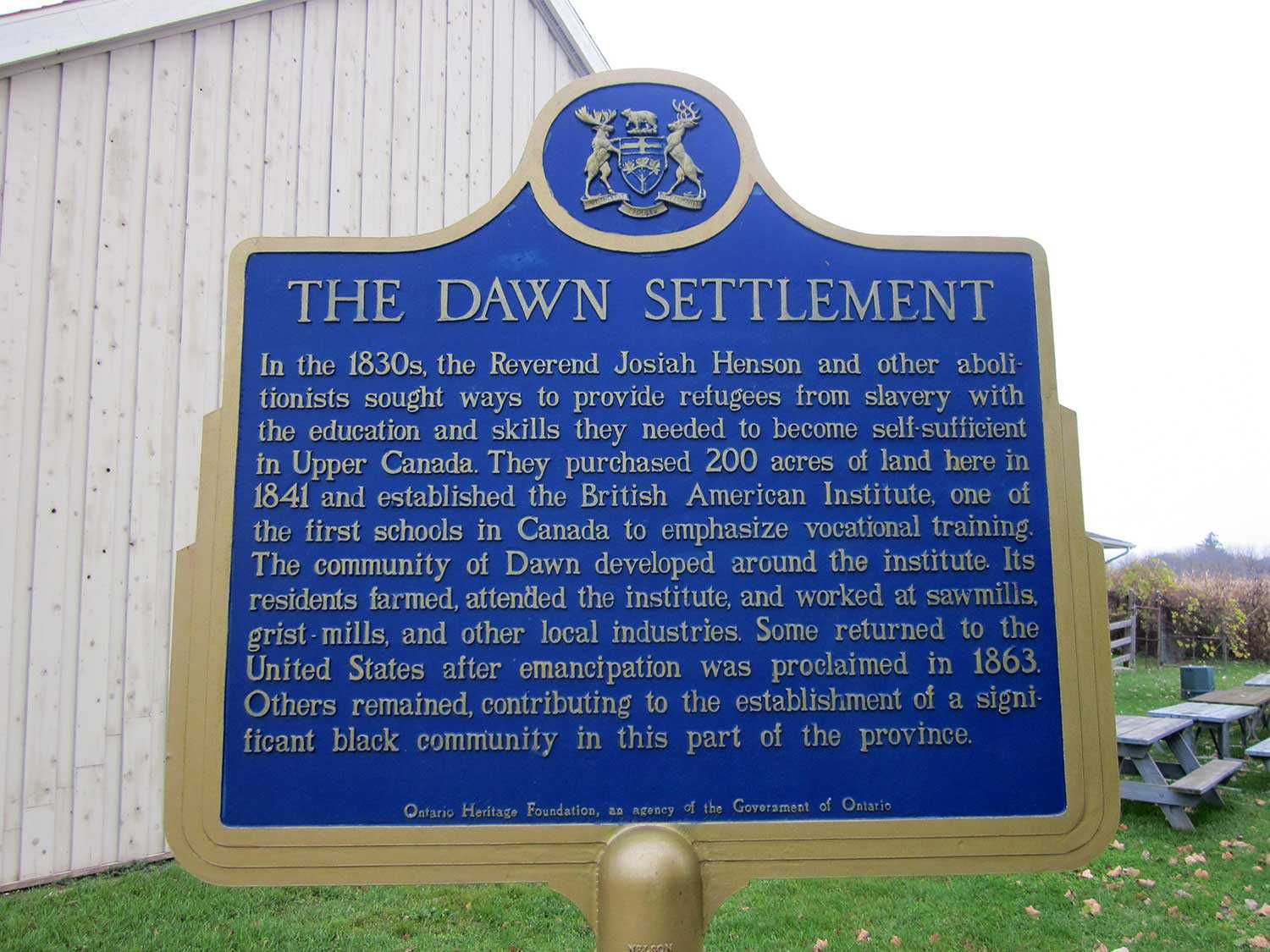

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

The end of an era

The years before the Great War are often romanticized as a series of garden parties, Sunday afternoon strolls in the park, stopping everything for afternoon tea, and a society rigidly divided by class. It is the last era to bear the name of a British monarch, Edward VII, 1901-10 – although the sentiments of the era extended well beyond Edward’s death as far as the end of the First World War.

We seem to know much – or think we do – about the Edwardians, thanks to their portrayal in popular culture through the likes of Titanic, Downton Abbey and the historical reality shows Edwardian Farm and Manor House. But what was Edwardian life like for the everyday Ontarian? How did the sentiments and attitudes of this age reveal themselves? To answer these questions, we delved into the Trust’s archival collection and found the detailed personal records of a middle-class Toronto family from that time.

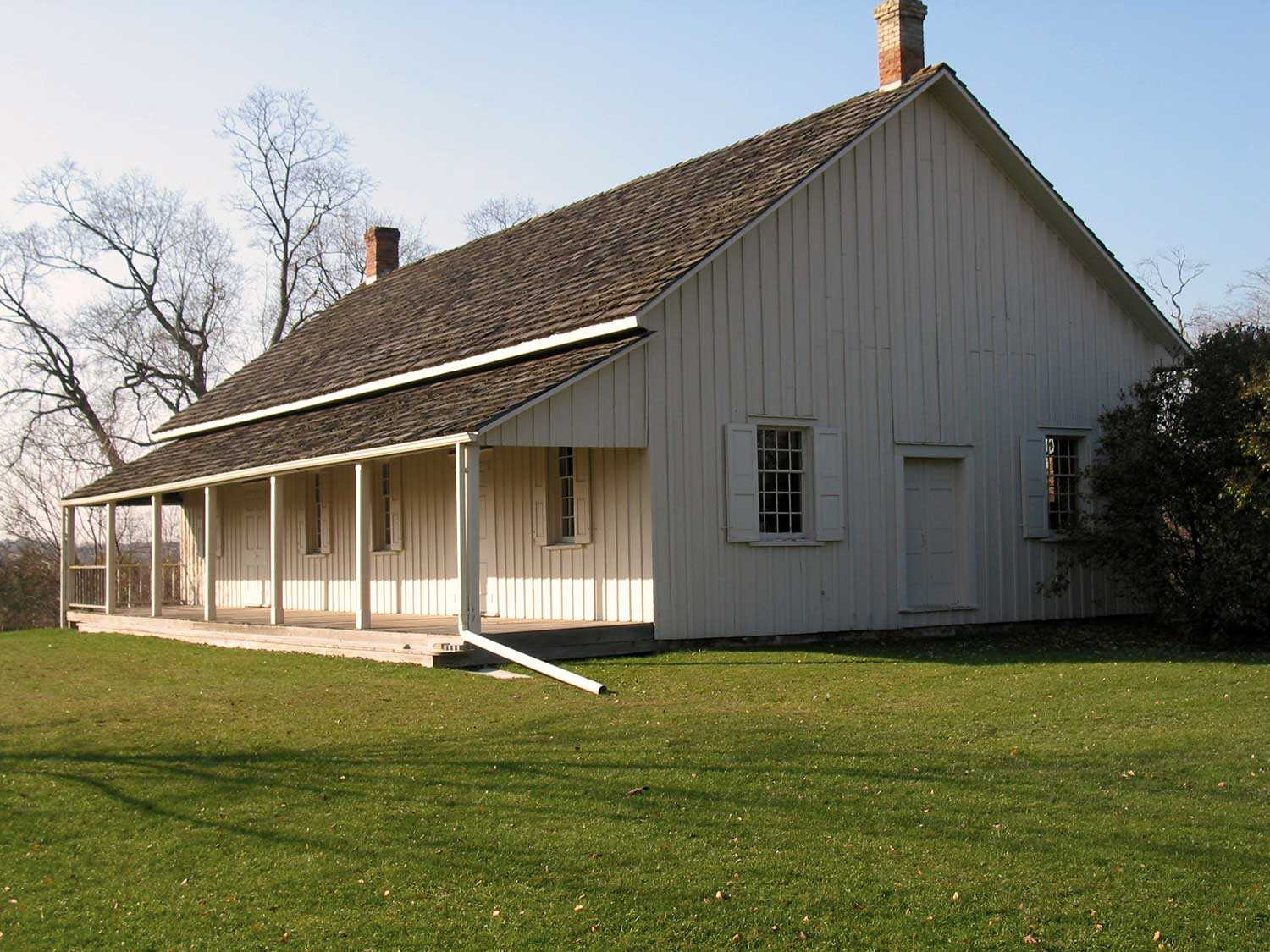

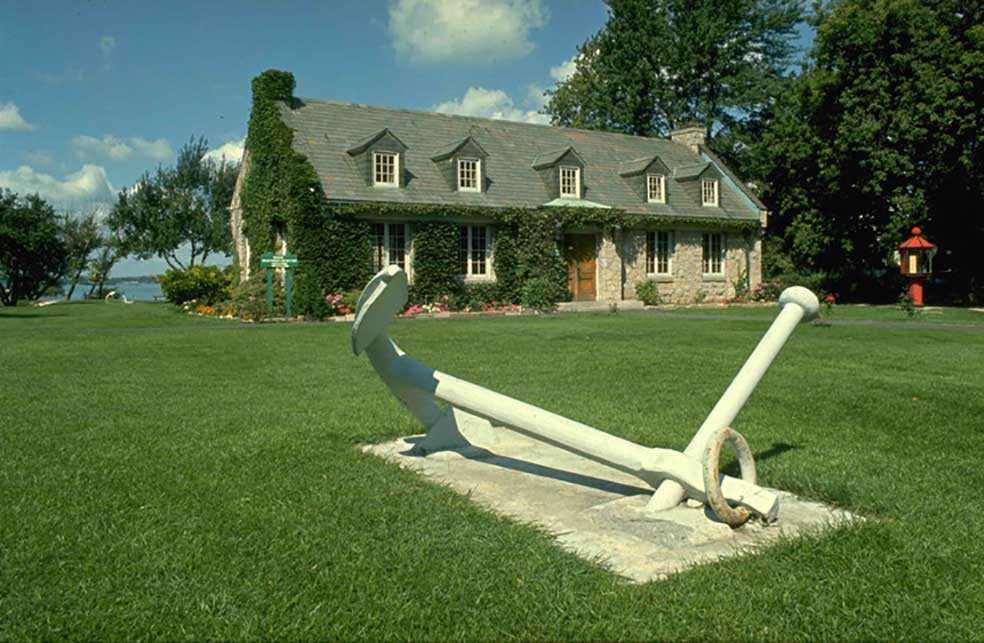

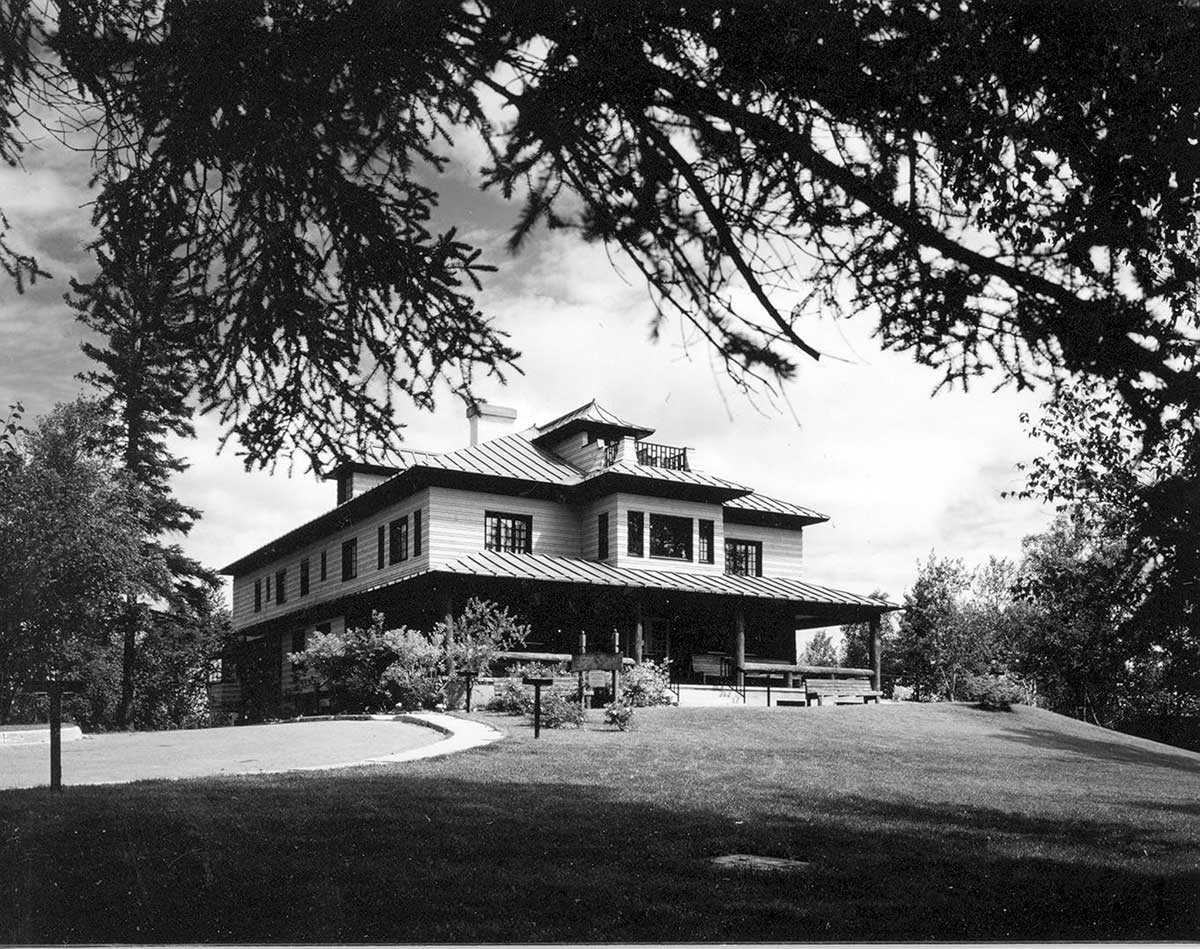

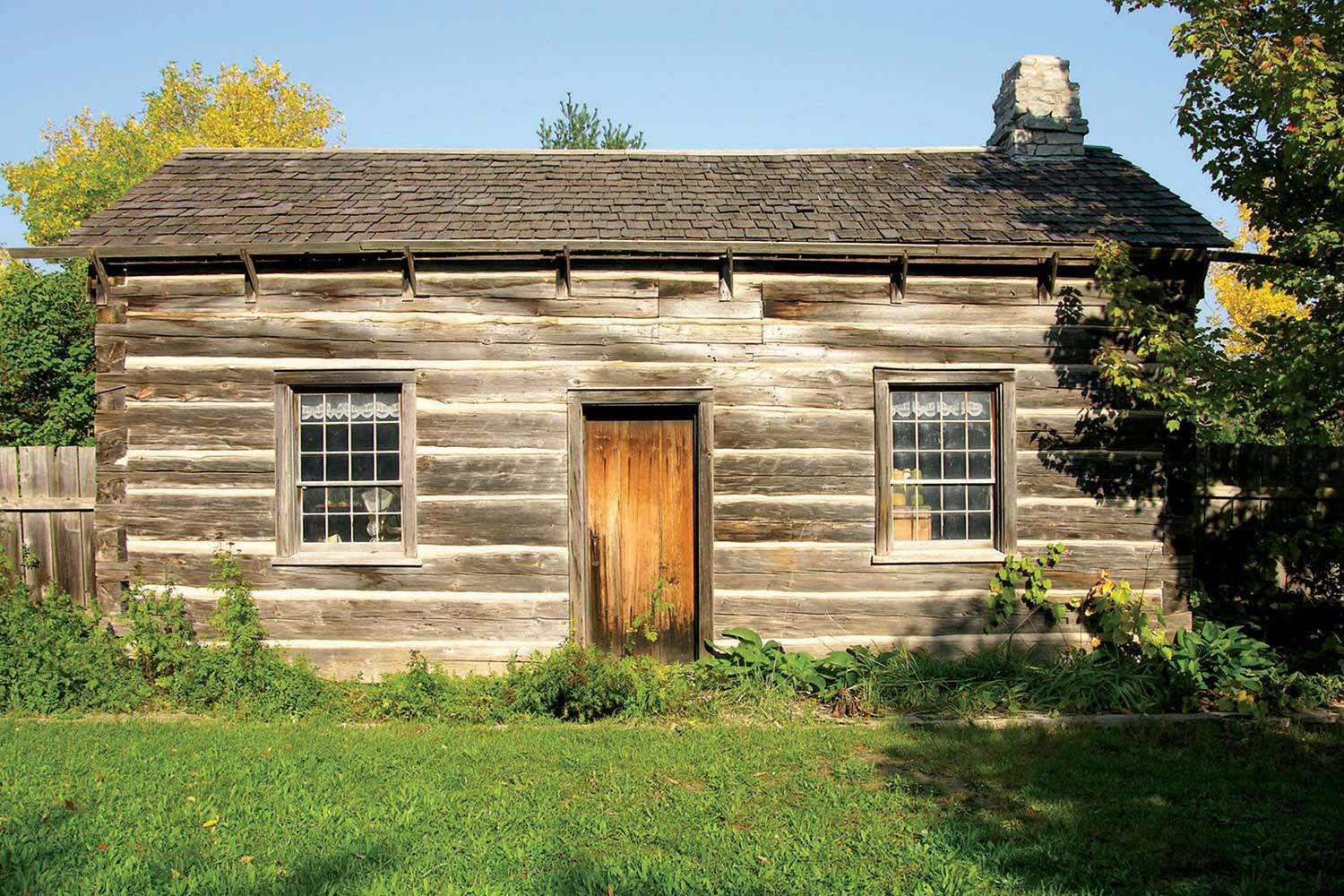

The Trust owns and manages Toronto’s Ashbridge Estate and is fortunate to have a major archival collection associated with the family. The Ashbridge family lived in the Toronto area from the late 18th century, but a large portion of the collection depicts their life during this pre-First World War era.

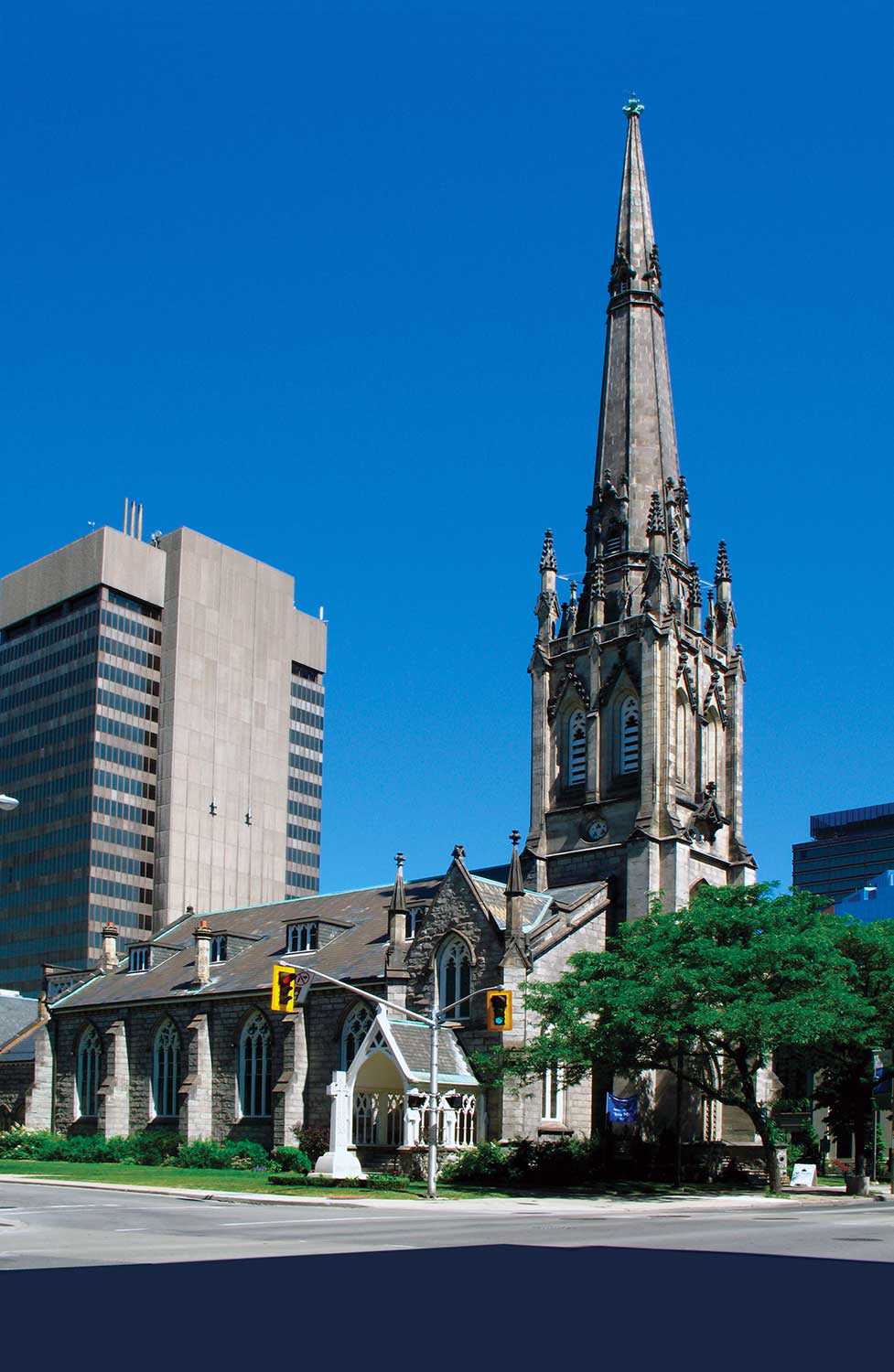

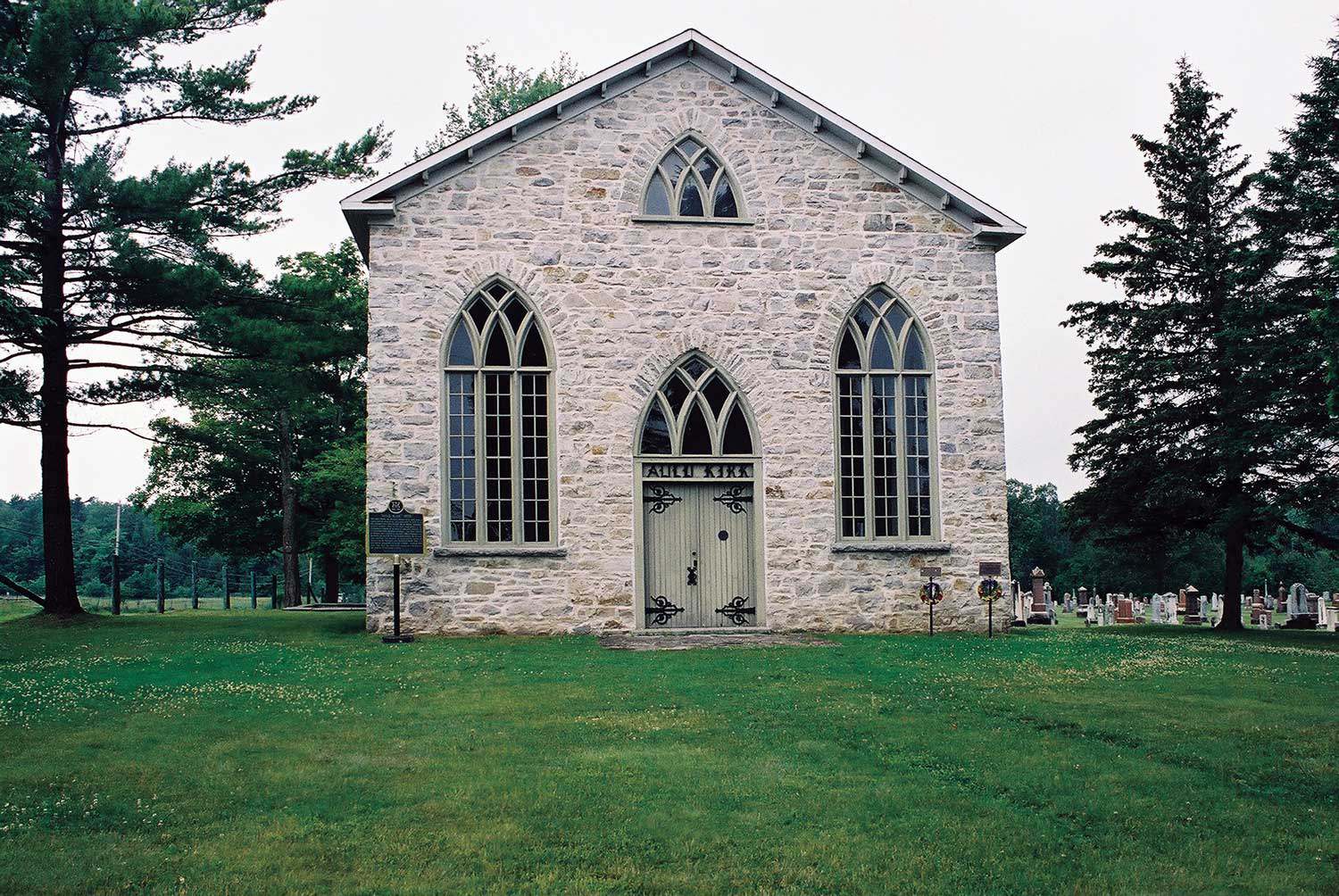

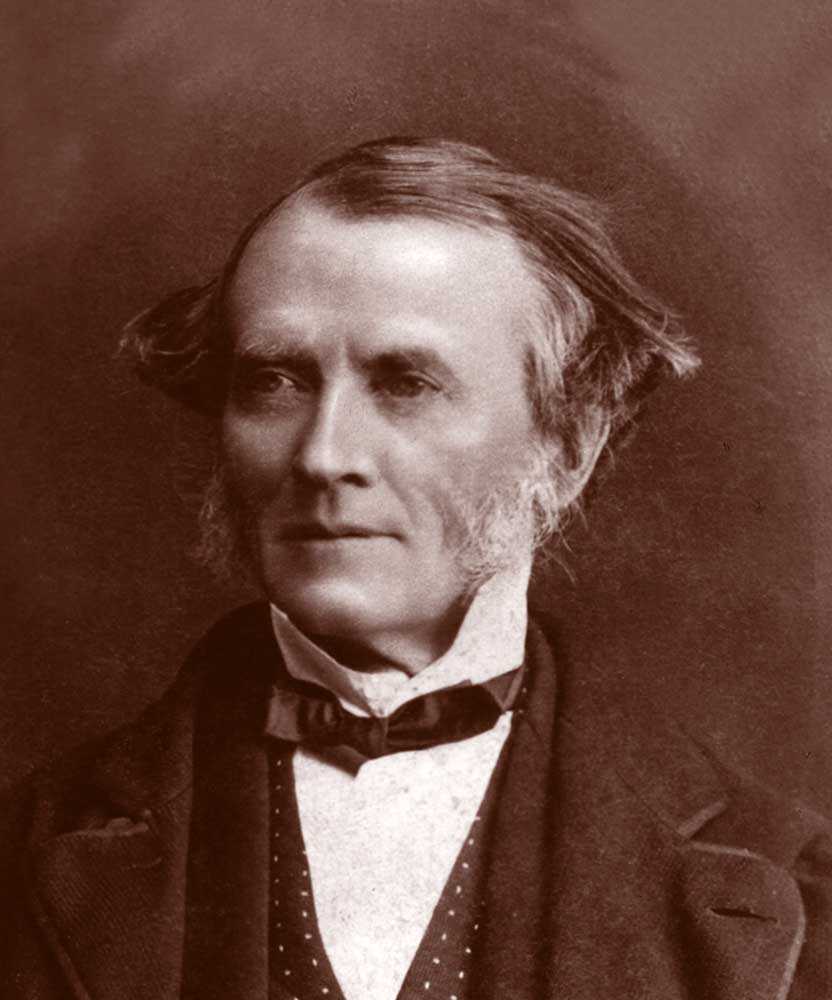

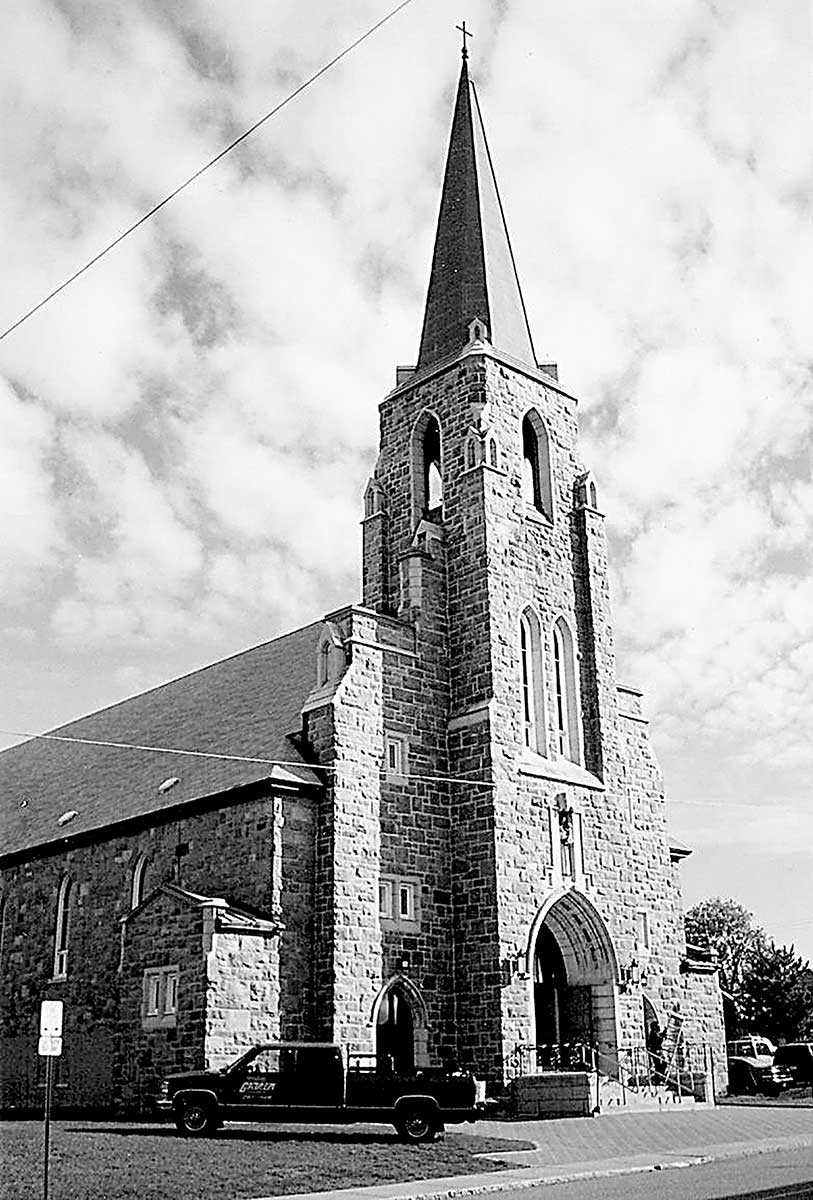

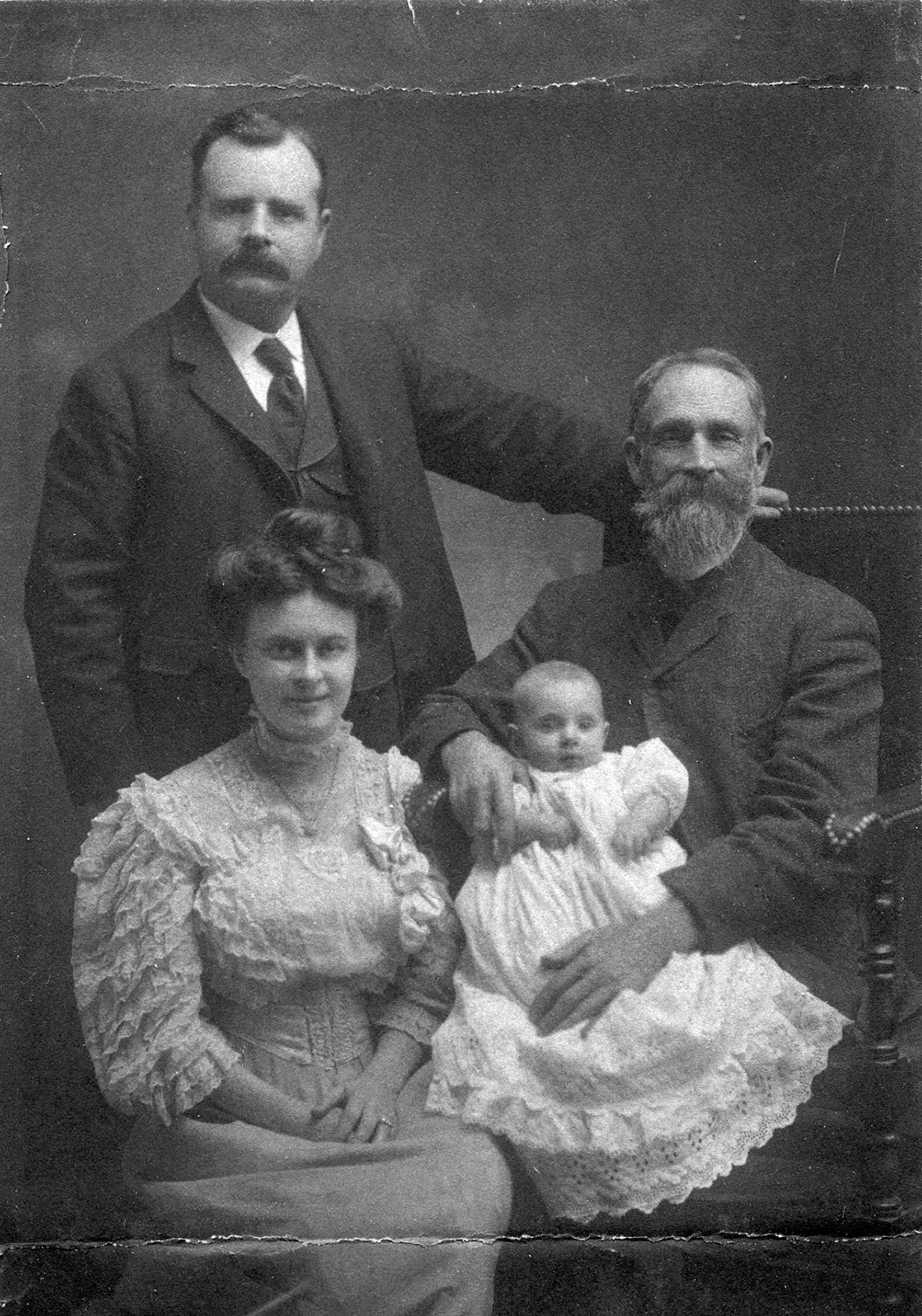

The courtship of Wellington Ashbridge (1869-1943) and his future bride Mabel Davis (1879-1952) is captured in a series of revealing letters. The two met at the Queen Street Methodist Church near their east-end homes. They wrote to one another while Wellington worked as a civil engineer in Edmonton in 1902-03. These courtship letters depict the reserved and old-fashioned temperament of the day. Only after months of writing and an official engagement did they begin to address each other by their first names. While the letters document their love and affection for one another, they also offer a captivating glimpse into middle-class Edwardian life.

For a young woman, Mabel had a great deal of responsibility. Prior to her marriage to Wellington, Mabel worked long hours at the Toronto Railway Company offices as “No. 3 cash counter,” often taking the trolley (streetcar) to work from her suburban home and forming friendships with the women with whom she worked. She helped take care of her mother, who suffered from poor mental health. The letters display her agonizing over a decision to send her mother away to an asylum – the only care option (other than staying with the family) that was available at the time.

With her mother unwell, Mabel took care of the household and often fell behind on chores; she repeatedly mentioned being exhausted. She would set her alarm for 3:30 a.m. to finish laundry from the previous day before she left for work.

Mabel enjoyed typical leisure activities, including: playing the organ, attending church services and social events, making hats, going for strolls, driving in the new “open car,” sitting on her veranda with friends, going to plays and, of course, “taking” tea – one of the most stereotypical Edwardian activities.

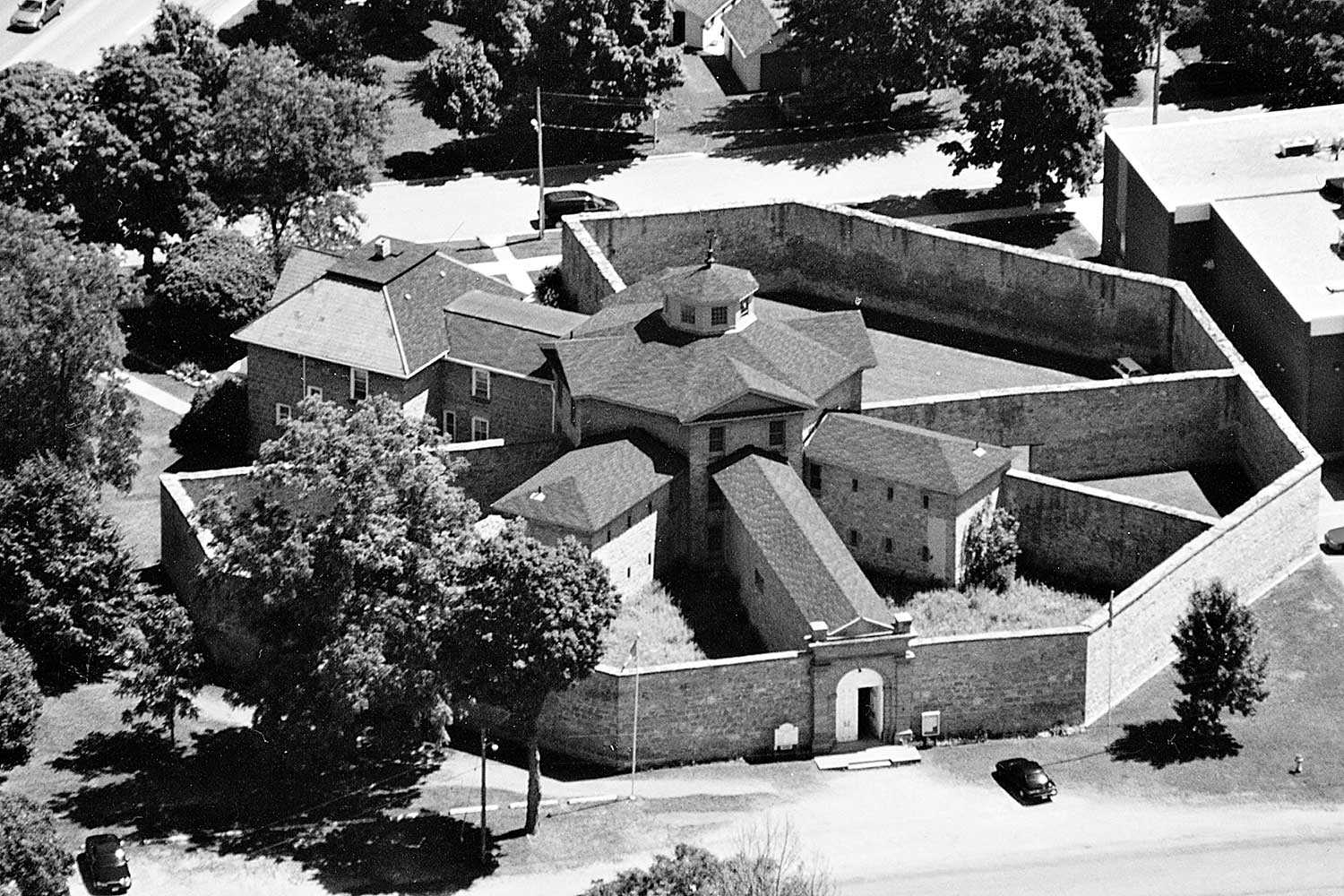

After Mabel and Wellington married, they moved out West and their two daughters were born – Dorothy in 1905 and Winifred “Betty” in 1907. In 1913, Wellington returned to Toronto with his young family to supervise the subdivision and sale of Ashbridge landholdings for suburban development – an episode typical of this period of rapid urbanization.

There is little direct evidence left by Dorothy and Betty from before the war. Through Mabel’s detailed account books, however, we can gather information about their childhood. Dorothy and Betty had comforts not afforded to many children of the era – such as new dresses, coats, books and music lessons. We also know that they participated in popular activities for children at the time – including sending and receiving Valentine’s Day cards, first popularized during the late Victorian era.

The years before the war were fondly remembered and recorded by the Ashbridge family, several of whom experienced it in their youth. Mabel shared in a letter to Wellington the following poem that she had submitted for a contest:

"The future is not given for man to know

Else all would be confusion in life’s race,

But onward, upward ever toiling slow

He’ll reach at last the very throne of grace."

There is clearly a sense of optimism, progress and piety in these lines, which we might infer as typical of the times. But, as history was to prove, the hopefulness expressed by Mabel – and undoubtedly shared by many in society – would soon be severely tested by the horrors of modern warfare. [All images courtesy of the Trust’s Ashbridge Collection.]

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)