Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

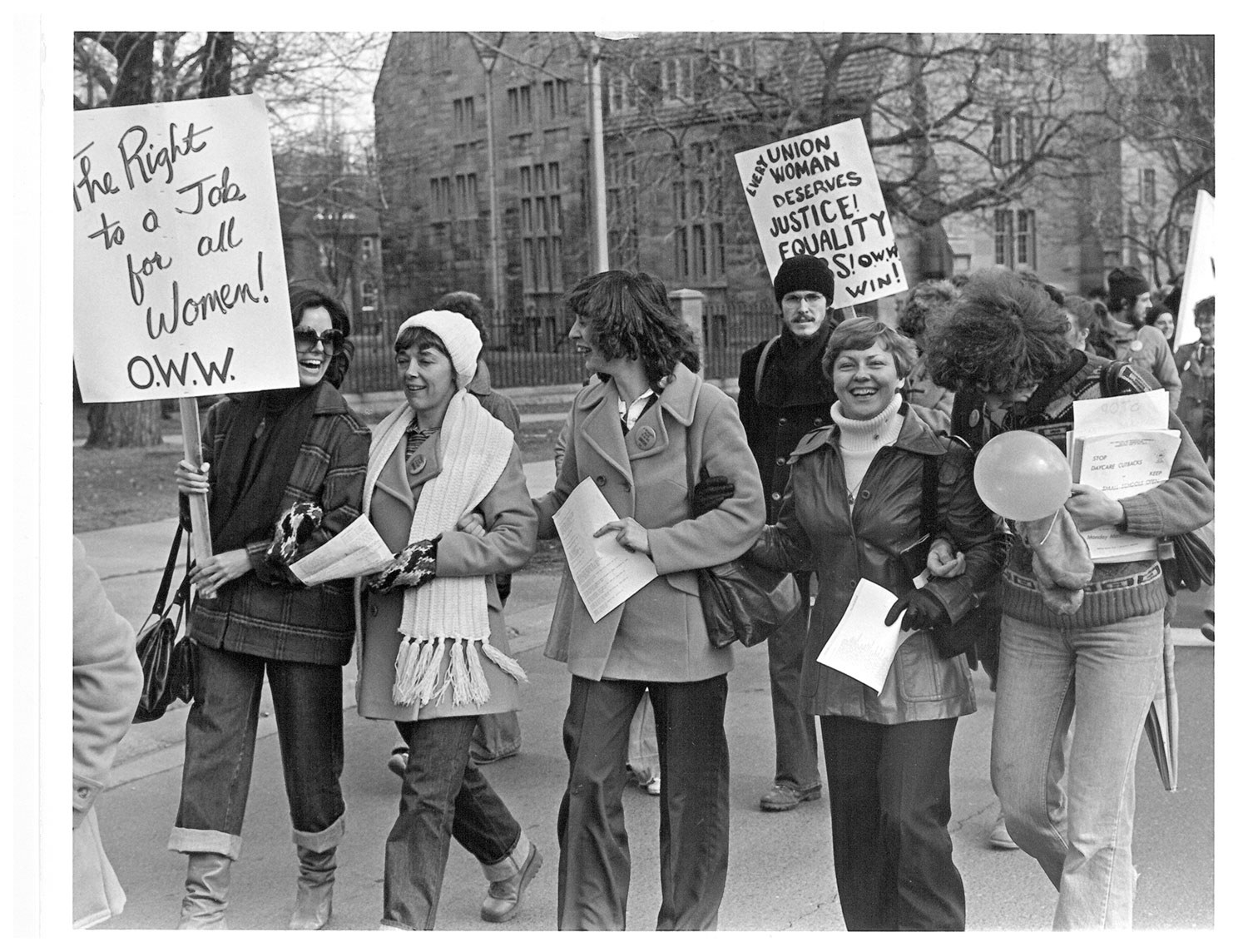

- Women's heritage

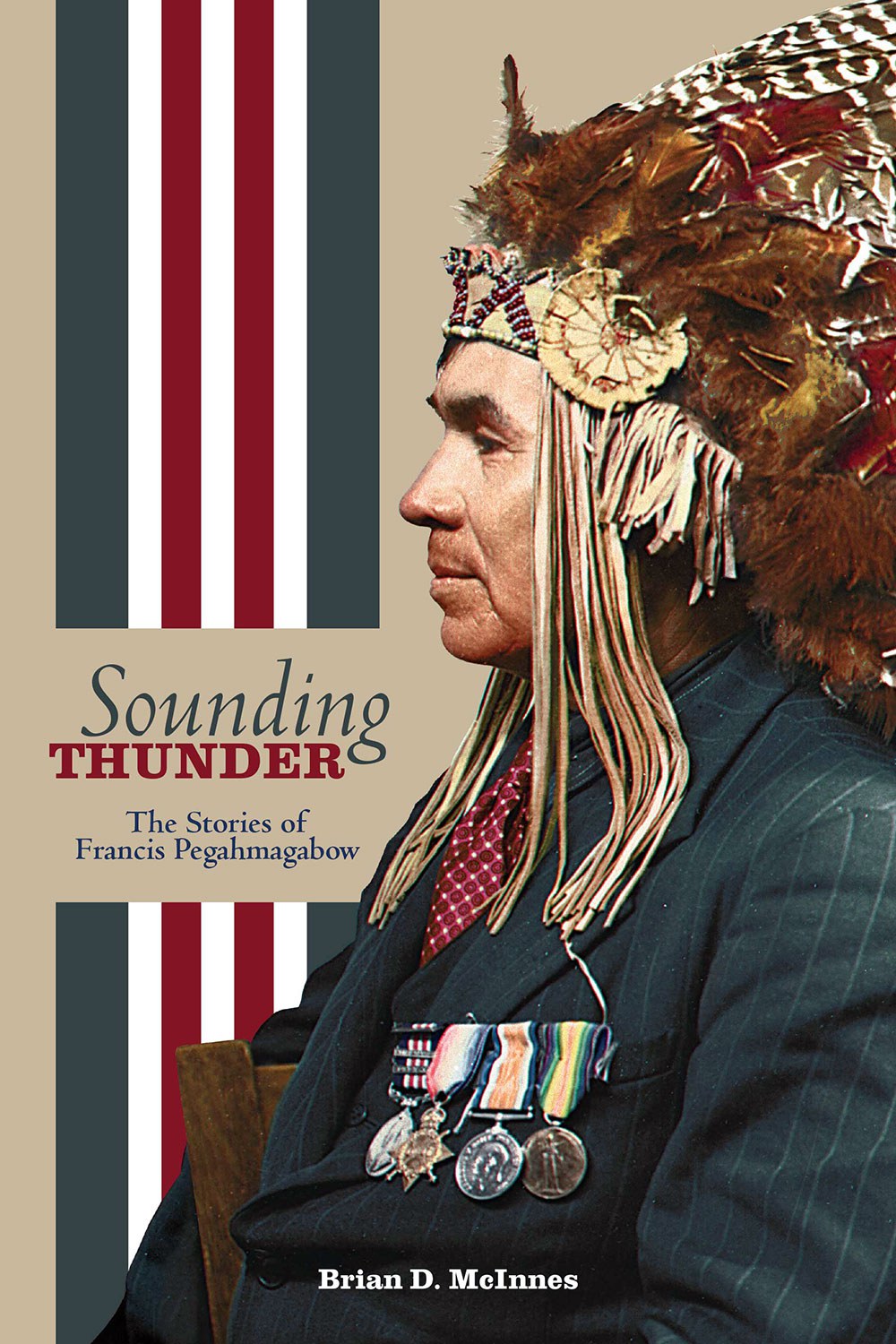

Suffrage and Indigenous women in Canada

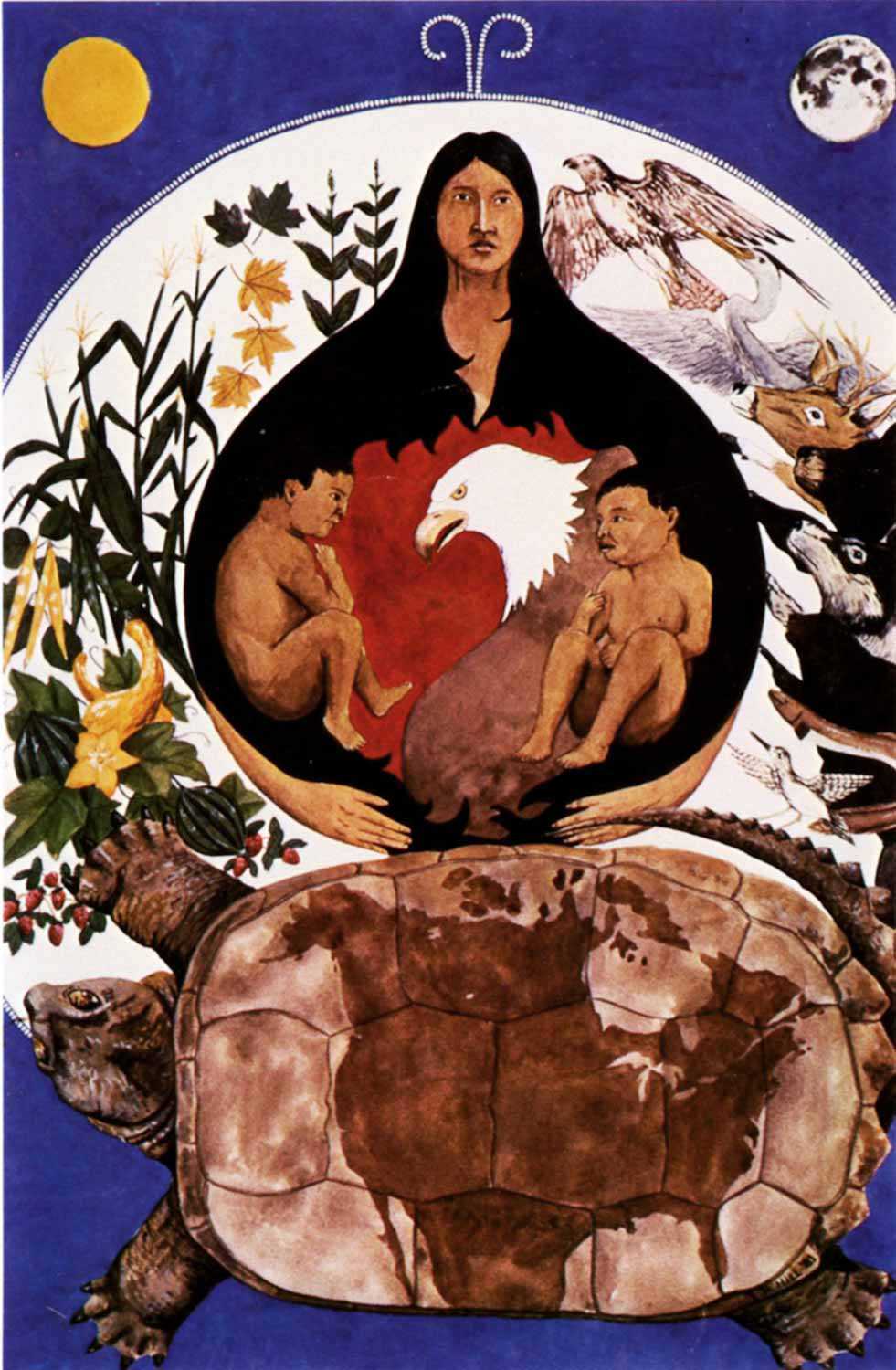

"We know that we are leaders. We are carriers of culture, of song, of hope, of persistence and incredible perseverance. By virtue of our still being here, we know we have won."

What has it been like to grow up in a society only now beginning to take note and respect the contributions of Indigenous women? When asked, far too many of us are taken back to being the direct recipients of our mothers’ (and fathers’) Indian Residential School experiences before we knew that such things even existed. What was just was, and illumination of the rocky road that I and many of us have travelled to academic or business success did not get revealed, much less healed, until we were ourselves parents and grandparents. In some cases, we made our own children walk the same pathway to hell. We had to swallow the invisibility of self, choke on the neverness of our lives, cloak our hurts in silence and surrender our minds and, far too often, our bodies to defeat.

Navigating our way through troubling conversations, too-early sexualization and confusing forms of neglect, we absorbed a multitude of teachable moments along the way. But what were we learning? And what did this all mean for ourselves, our daughters and the burgeoning missing and murdered phenomenon we are faced with now? These questions and unanswerable “knowings” cannot be changed or erased with time. We, as Indigenous women, whose hearts have long hovered just over the ground, far too close to broken,1 have now been tasked with addressing and deconstructing the entire circus of intergenerational effect and defining what it will take to change the current trajectory of Indigenous feminine beingness in this country. Beyond Trudeau’s “because it’s 2015,” we know that there is a multitude of below-the-tip-of-the-iceberg issues that must be acknowledged before we can ever be truly healed.

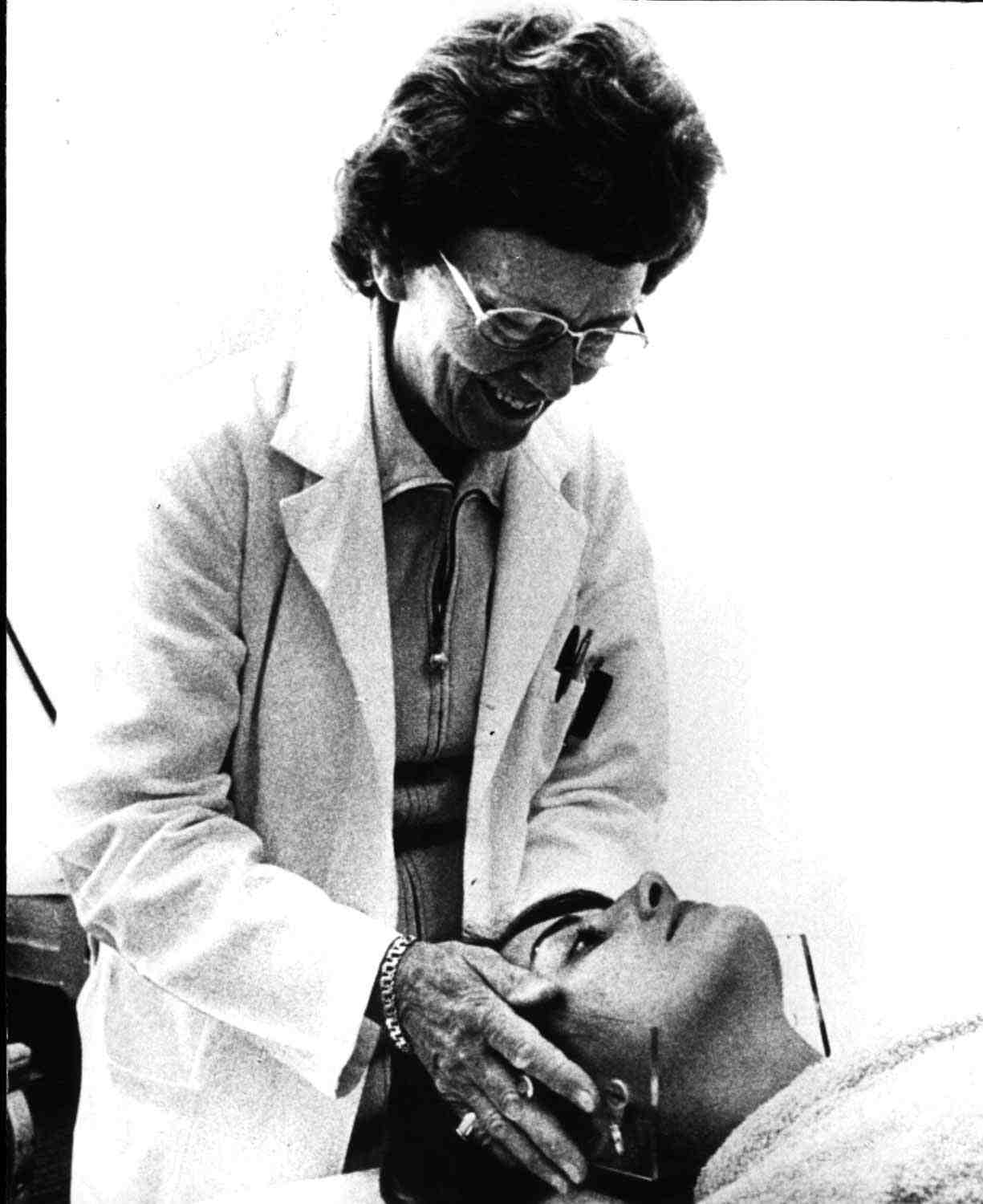

And, yes, we are becoming all those things that we were once denied; teachers, academics, chiefs, engineers, architects and doctors. We will continue to become, our numbers growing. And we will not stop now. We were here yesterday, we are here today and we will be here tomorrow. Suffrage? We have suffered 600 hundred years of rage, oppression and loss – and once our traditional governance systems were destroyed and voting was enforced, we endured 67 years of being denied the right to vote in our own communities for our own leaders. The unfettered ability to vote in Ontario and Canada did not arrive for us until 1960, even though Indigenous women were given the right vote in 1867 – IF they gave up their right to their heritage and homes and left their Reserves, who would do this?

We have our heroes, “women who raised awareness of the sexist clauses of the 1876 Indian Act through activism and legal challenges. The Indian Act is a piece of antiquated Canadian legislation that defines the word colonial in a country that has long denied its own history. Mary Two-Axe Earley (Mohawk) fought her eviction from Kahnawake reserve in Québec and publicized it at the International Women’s Year conference in Mexico in 1975. In 1973, the Supreme Court heard the discrimination cases of both Jeannette Corbiere Lavell (Anishinaabe) and Yvonne Bedard (Haudenosaunee). In 1977, Sandra Lovelace (Wolastoqiyik) brought her case to the United Nations Human Rights Committee. The Committee ruled in her favour on 14 August 1979”(Historica Canada). More recently, the 2009 McIvor decision put Indigenous women on a more equal footing with male members so that they could protect their children and grandchildren from expulsion from their home territories. In 2017, Lynn Gehl won her own fight against sexual discrimination in the Indian Act.

So, where does this bring us when we speak of women’s rights, mobilizing the ability to vote and wielding influence in today’s world? Indigenous women have ensured the continuance of their cultures and languages in the face of colonial hostilities, public marginalization and political silencing. We now have a government that has said “yes,” but to what effect? We have yet to see whether using the vote to force change will continue into the next election. We are not yet convinced it has paid the kind of dividend our people had hoped for. But Indigenous women are pragmatic organizers and will no longer accept defeat. Together, they are lifting their hearts as one.

1 A Cheyenne proverb says: “A nation is not conquered until the hearts of its women are on the ground. Then it is done, no matter how brave its warriors nor how strong their weapons.”

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)