Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

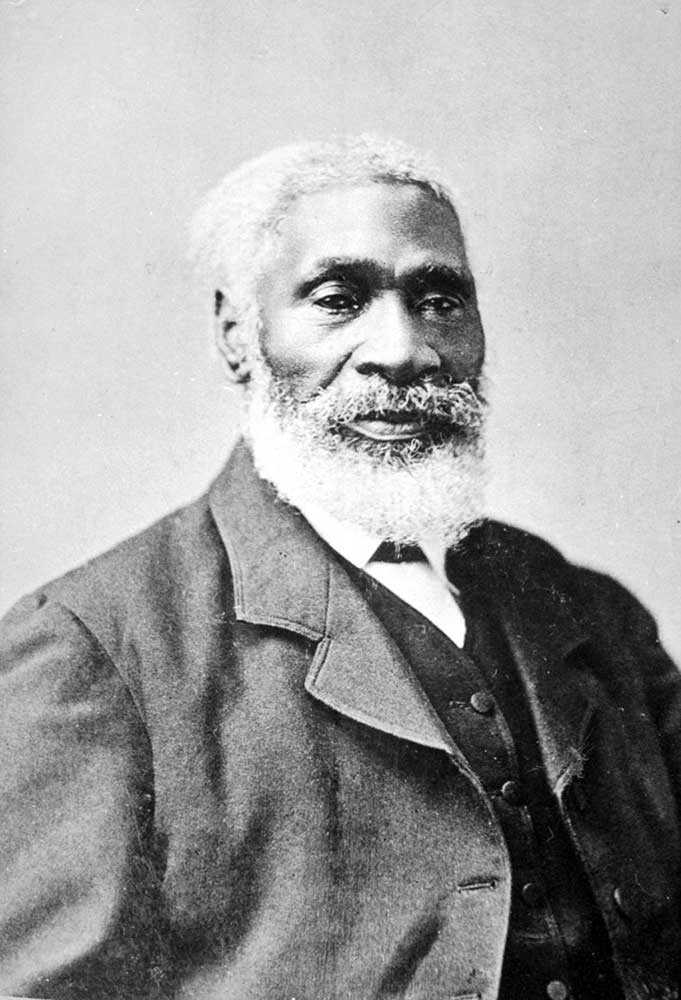

Celebrating the International Year for People of African Descent

"“This International Year offers a unique opportunity to redouble our efforts to fight against racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance that affect people of African descent everywhere.”"

Navi Pillay, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

The United Nations (UN) has designated 2011 as the International Year for People of African Descent. The UN recognizes that, worldwide, people of African heritage still face racial discrimination and oppression as a result of slavery and colonization.

In declaring the year’s theme as “Recognition, Justice and Development,” the UN has called on member states to take steps to redress this oppression. Responding to this call from the UN, the Ontario Heritage Trust has dedicated this issue of Heritage Matters to Ontario’s 250-year African- Canadian heritage and history.

Ontario’s Black heritage dates back to the period of the French regime. As early as 1745, Black oarsmen – enslaved and free – worked in the lucrative fur trade. We find evidence of these Black boatmen working in Toronto, Cataraqui (Kingston) and Niagara Falls.

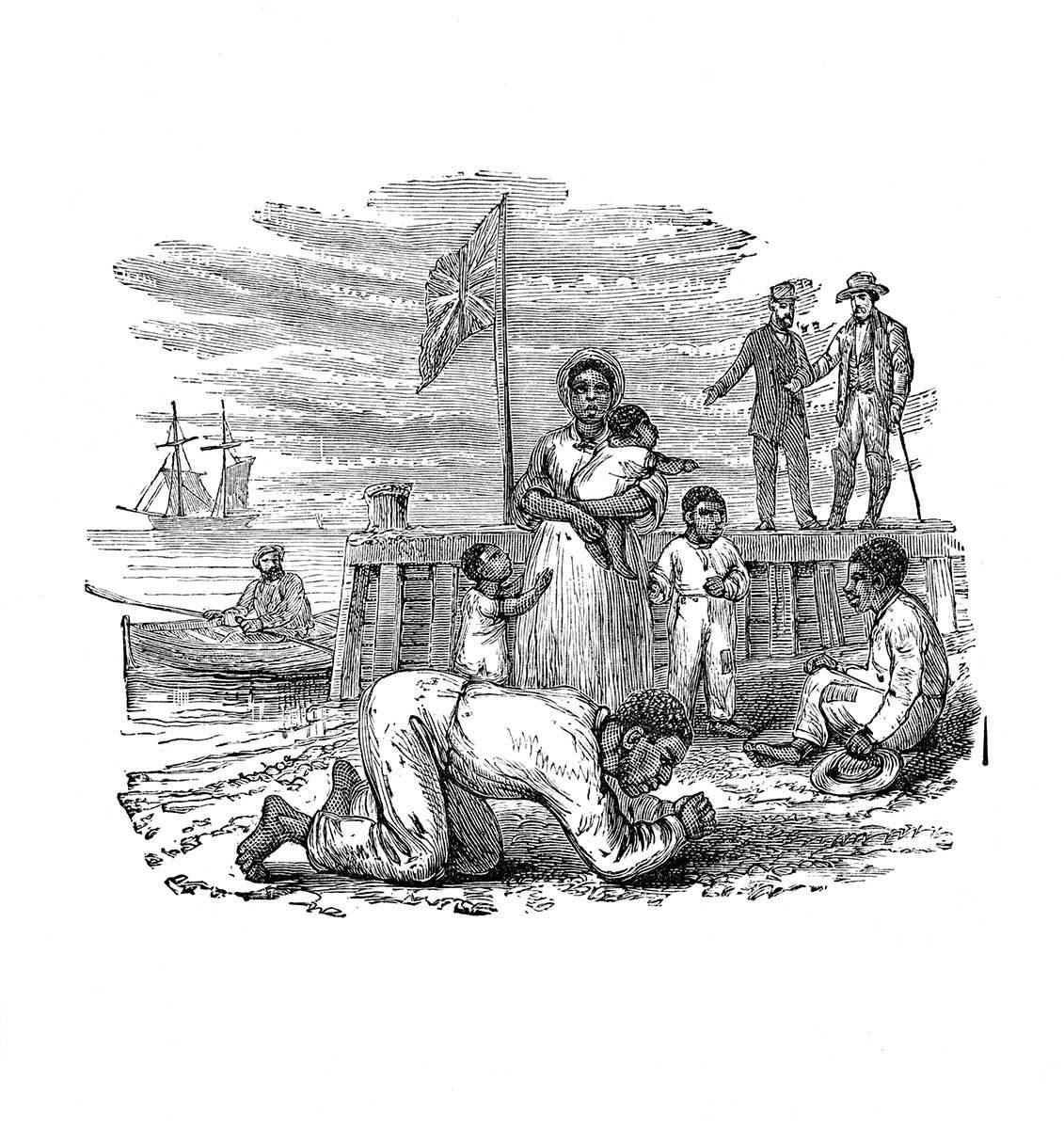

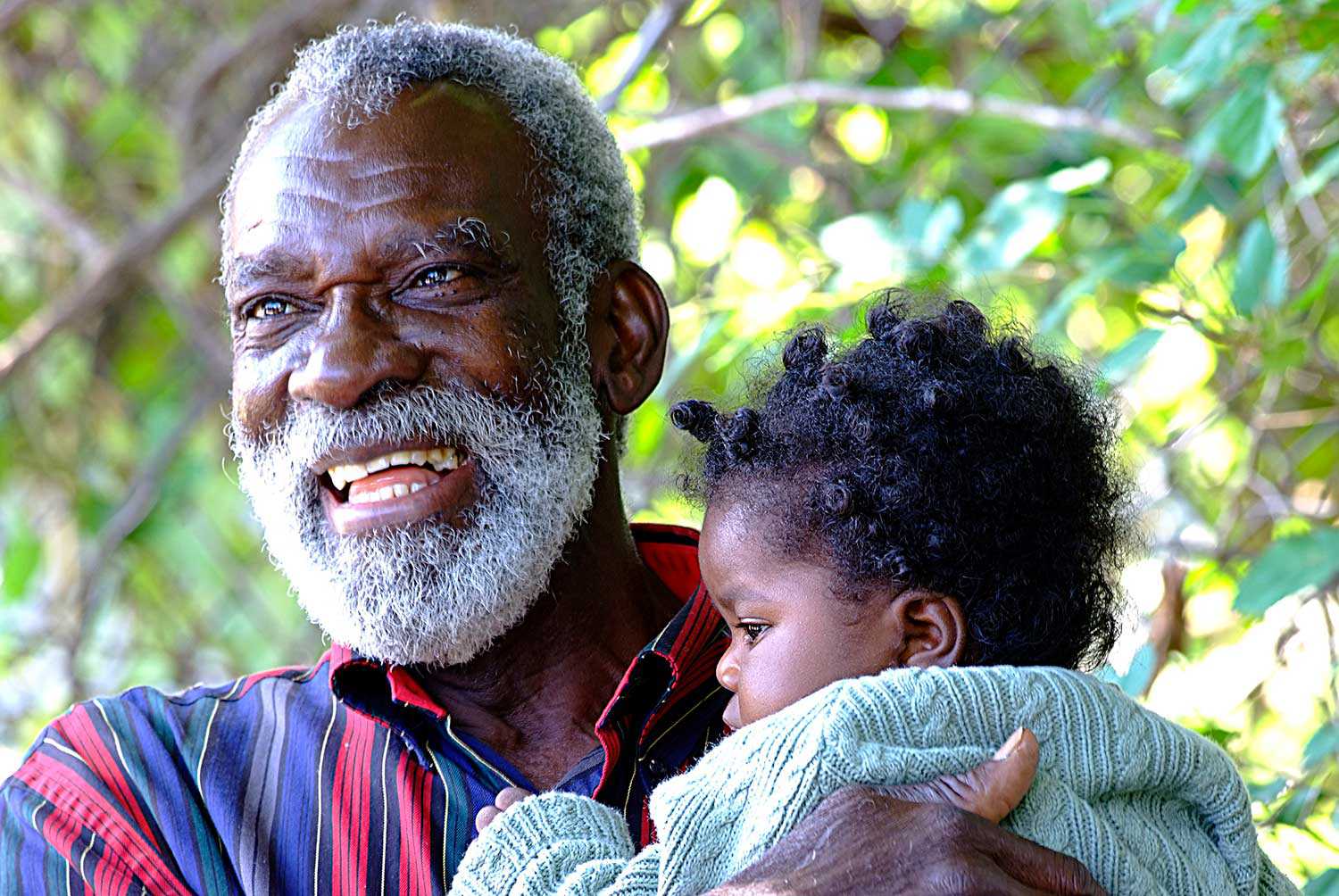

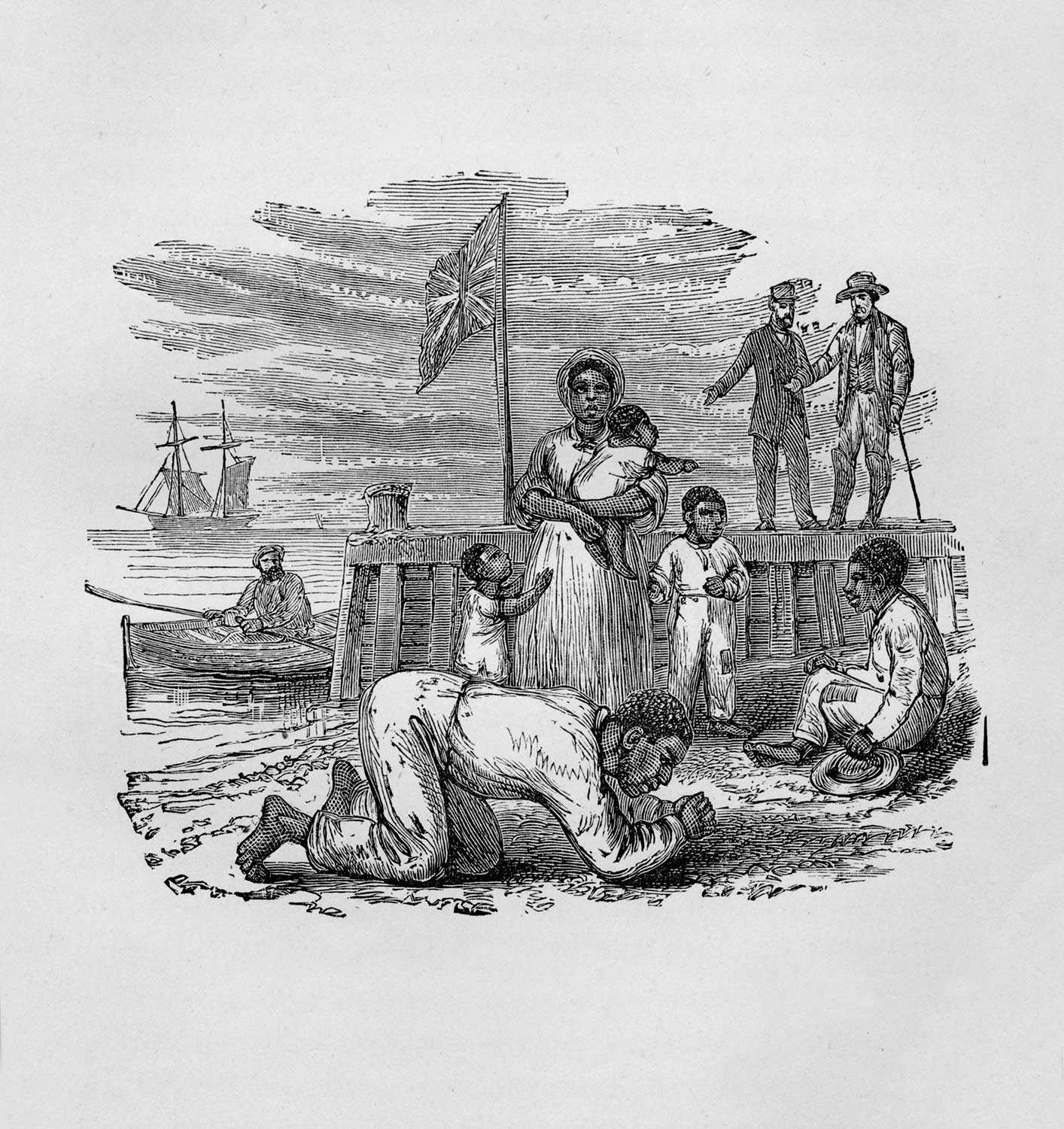

This heritage was created and shaped by Black people from diverse origins and experiences. In addition to Blacks from the ancien régime, we have Loyalist military families who gained their freedom as a result of fighting for the British. There were also enslaved Africans who laboured for their white Loyalist owners. There were the 19th-century Underground Railroad immigrants from the United States. As the century progressed and the 20th century unfolded, Black people from the Caribbean began contributing to Ontario’s Black history. And, after the Second World War, immigration from continental Africa increased.

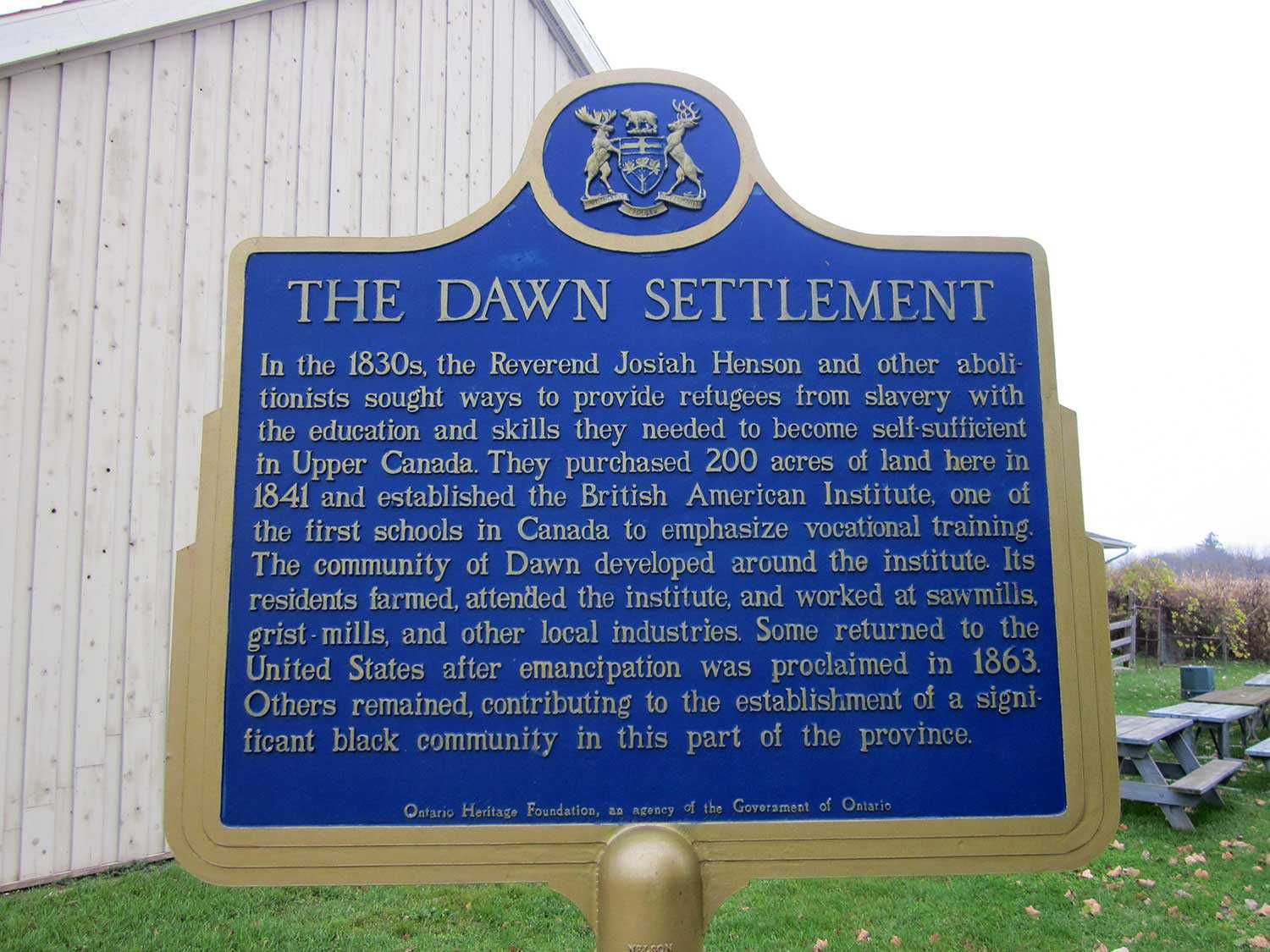

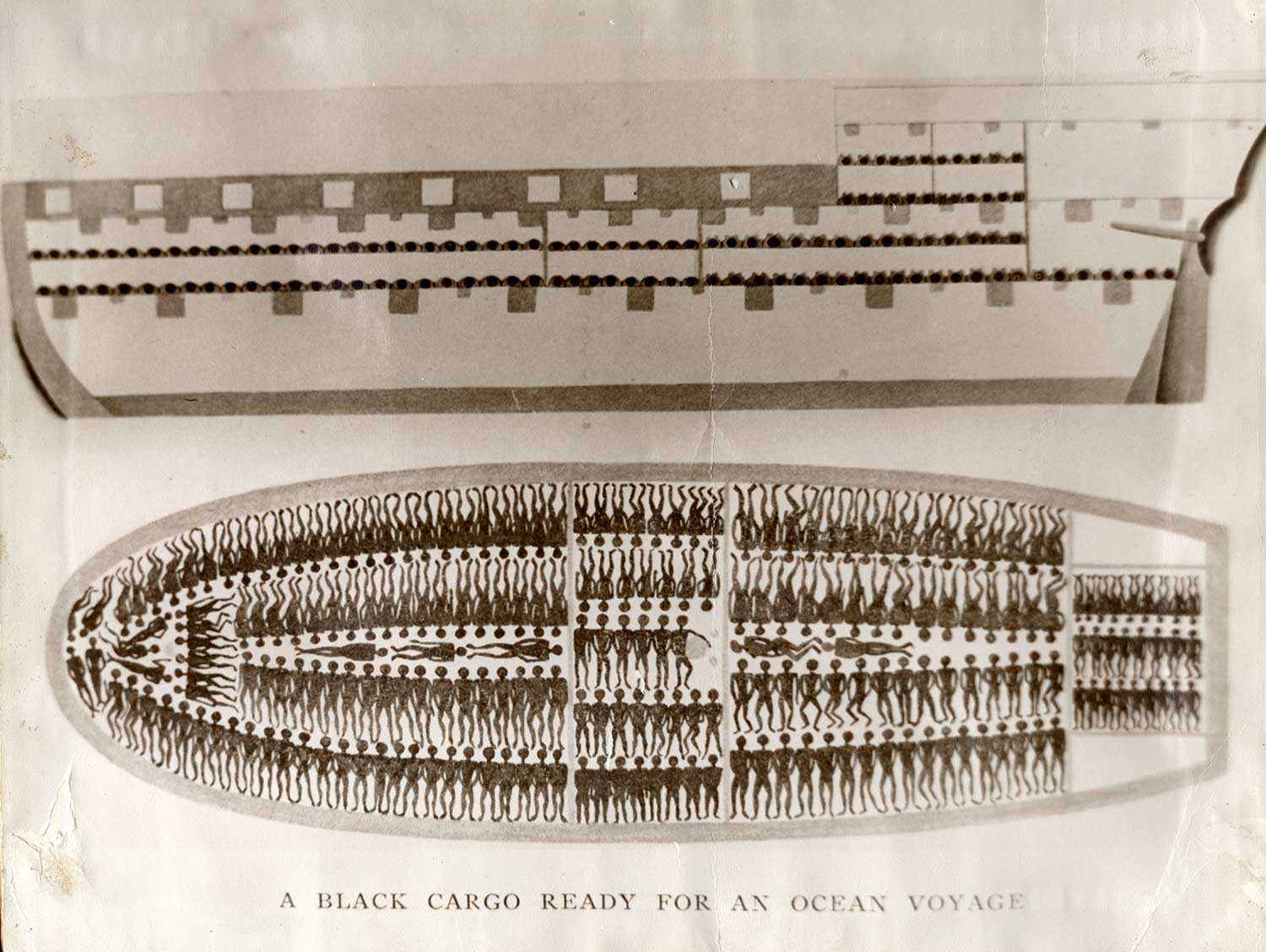

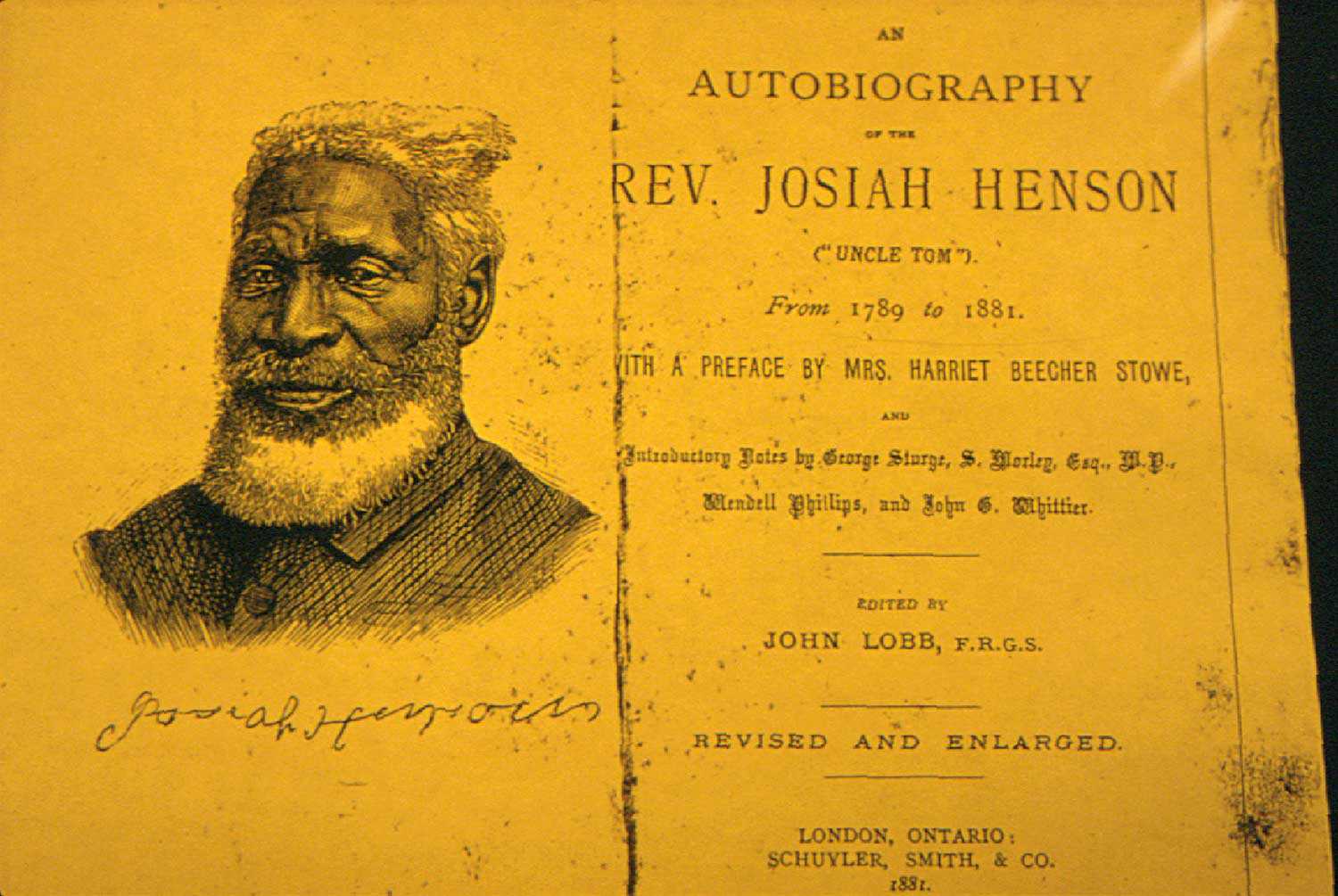

Here are just a few of their stories. Born and raised in Senegal, West Africa, Richard Pierpoint was kidnapped and sold into the transatlantic slave trade, and ended up in the northern states. During the American Revolutionary War, he escaped from slavery and fought on the side of the British, later settling in Ontario; he also fought for the British during the War of 1812. Enslaved Ontario woman Chloe Cooley was an early human rights champion. Josiah Henson opened the first industrial and manual trades school in Canada. And, in more recent times, Jamaican- Canadian Rosemary Brown changed the Canadian political landscape when she became the first Black woman to run for the leadership of a federal party – the New Democratic Party – in 1972.

Black Ontarians throughout the past two and a half centuries have built communities, towns and cities, have raised families and have used their skills and talents for the development and progress of the province.

Though the accomplishments, contributions and achievements of Black Ontarians are legion, the history of Black people in Ontario has been underrecognized, marginalized or forgotten. And these were no mere accomplishments. Pierpoint, for example, helped found a new nation and country. Despite the tremendous gains African-Ontarians have made, racial discrimination continues to thwart our steps and has had a negative impact on the development of our communities.

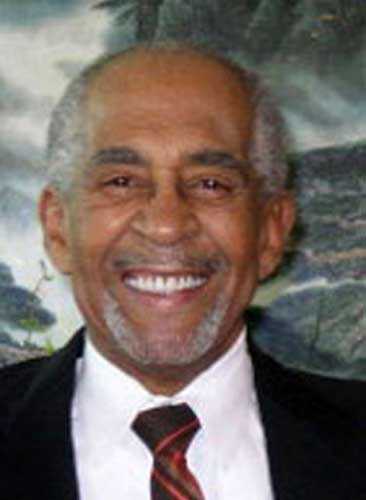

For example, Senator Donald Oliver notes in the article “What it Means to be Black in Canada” (The Mark, July 14, 2011) that Blacks in Canada continue to face severe unemployment, racial profiling and discrimination in the courts. Further, Oliver notes that popular media continue to present Black Canadians in demeaning ways: as poverty stricken, pathological and criminal. Oliver further identifies the invisibility of Black history as one of the reasons that Black people continue to face various forms of racial discrimination.

According to the 2009 Statistics Canada police report on hate crimes, “Blacks continue to be victimized by hate crimes more than any other group.” Hate crimes directed against Black Ontarians and Canadians have increased by 34 per cent since 2008 – particularly in Toronto, Ottawa and the Kitchener- Waterloo area.

Some of the leading authors and scholars of Ontario’s Black experience – found here in this Special Edition of Heritage Matters – have responded to the call to make Black history visible and to use history as a tool to break down stereotypes and promote greater awareness of the province’s Black past.

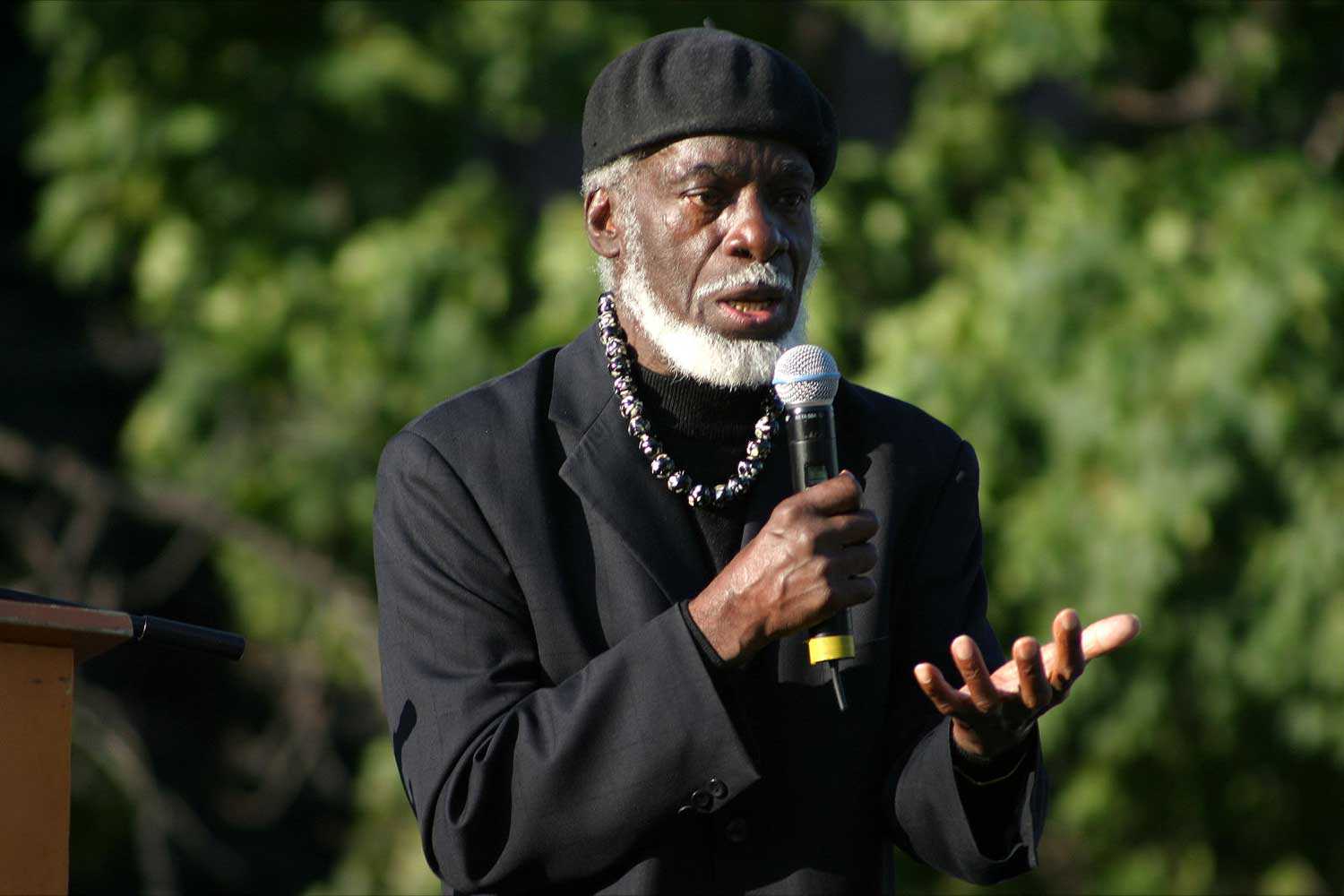

All the authors focus on one or all aspects of Black people as agents in the creation of their own history, and the need for recognition, justice and development for Black people. Rosemary Sadlier shows the role the Ontario Black History Society has played in ensuring that Black history be recognized and valued. Nina Reid-Maroney and Marie Carter both look at the accomplishments of some 19thcentury Black Ontarians beyond the Underground Railroad narratives. Karolyn Smardz Frost informs us of another UN project and its relevance for African- Canadian heritage. Adrienne Shadd highlights the stellar role and work of community historian and griot (storyteller) Wilma Morrison. Tamari Kitossa speaks to African-Canadians and the law, and how this law has been used as a double-edged sword in the lives of many Black Canadians. Afua Marcus reminds us that dance has always been an instrumental part of Black life by focusing on the life and work of Len Gibson. Mesfin Aman grounds us into the present by examining how civil rights leader Dudley Laws has changed the civil rights landscape in Ontario. And Thando Hyman explores the successes of the Africentric Alternative School and how this school has helped build pride among young Blacks.

Black Ontarians are aware that the arena of heritage, history and culture is a critical one in our struggle for our human rights. This issue of Heritage Matters is a step in that direction.

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)